Lesion and deep brain stimulator placement for OCD, adapted from Greenberg et al., 2010.6 (Right) Targets in axial view: 1a, anterior thermocapsulotomy; 1b, posterior target used for gamma ventral capsulotomy; 4, VC/VS site for deep brain stimulation. (Left) Targets in sagittal view: 2, anterior cingulotomy; 3, subcaudate tractotomy.

Interruption of the anterior cingulate gyrus was proposed roughly in parallel with the development of the peri-caudate operations, with investigators at the Massachusetts General Hospital being the first to significantly study and promote this procedure for depression and OCD.8 Follow-up of patients undergoing anterior cingulotomy using modern image-guided techniques found a 69% response rate in OCD, with no substantial long-term effects.9 Anterior cingulotomy has also been combined with subcaudate tractotomy in a procedure called limbic leucotomy.10 Response rates range from 36% to 50%,11 although it should be considered that limbic leucotomy is commonly performed as a staged procedure. Thus, the leucotomy population can be considered enriched with patients who did not respond or would not have responded to anterior cingulotomy. The precise mechanism of action for all these procedures remains unknown, with theories including interruption of reverberant cortico-striato-thalamic loops,12 disconnection of fronto-limbic networks, or release of inhibition on otherwise hypoactive brain areas.2

Given the frequent misconception of DBS as creating a “virtual lesion,” the success of ablative procedures naturally led investigators to propose trials of DBS as a customizable and reversible therapy for psychiatric disorders. This was first essayed by Nuttin and colleagues in 199913 in what is also the first recorded case series of DBS performed specifically for a psychiatric indication. That early report of “some beneficial effects” in three of four patients undergoing DBS at the anterior capsulotomy target for intractable OCD seeded ongoing investigations, which continued to show similar results.14,15 Over time, the target moved posteriorly, to a putative junction of the anterior commissure, internal capsule, and striatum.16,17 The new target has been referred to as “ventral capsule/ventral striatum” (VC/VS), and is also pictured in Figure 11.1. At this target, pooling data across multiple trial sites, the mean improvement in the Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (YBOCS) score was 38% (range 21–34%), with at least some clinical response in 72% of patients.16 Depression also improved, with a mean drop of 43% in the Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and 50% of patients meeting criteria for depressive remission.

This concomitant improvement in depression and OCD is a core feature of VC/VS DBS. It was therefore surprising when a recent controlled trial targeting major depressive disorder (MDD) with VC/VS DBS did not achieve a significant difference between active DBS treatment and sham DBS in patients with treatment resistant depression.18 This stands in contradiction to an initial pilot study showing a 53% response rate and 40% remission rate for MDD at the same target.19 It also conflicts with reports of successful DBS for MDD when targeting the nucleus accumbens, a site that is easily within reach of electrical fields generated from a DBS lead in the VC/VS.20,21 Resolution of this conflict between results in open-label and controlled clinical trials is a major task for psychiatric DBS investigation in coming years, although it may first require advances in our understanding of the neurobiology of depressive illness.

That search for the etiology and neuro-circuitry of MDD underpins the second main thread of psychiatric DBS development: an attempt at a “rational therapeutics,” where targets are identified by imaging and then used for DBS treatment. Helen Mayberg and colleagues performed extended neuroimaging studies of patients with major depression and repeatedly identified Brodmann area 25 (also called “Cg25” for “cingulate gyrus 25”) as hyperactivated compared to healthy volunteers. Figure 11.2 shows the overall circuit identified by the Mayberg group and compares it to the OCD circuit. Following again on the idea of DBS as a “simulated lesion,” her team attempted DBS of this site. Four patients from an initial pilot group of 6 achieved remission, and long-term follow-up of a subsequent cohort showed a 43% remission rate with follow-up as long as 6 years.22,23 Intriguingly, imaging of patients undergoing DBS at the VC/VS target has suggested changes in metabolism at Cg25, suggesting that these two targets may affect a common circuitry through alternate routes.23,24 Unfortunately, that commonality also extends to clinical trials: as of this writing, a clinical trial of Cg25 DBS for MDD had also failed to reach its endpoint, despite robust effects at that same target in several other investigations.

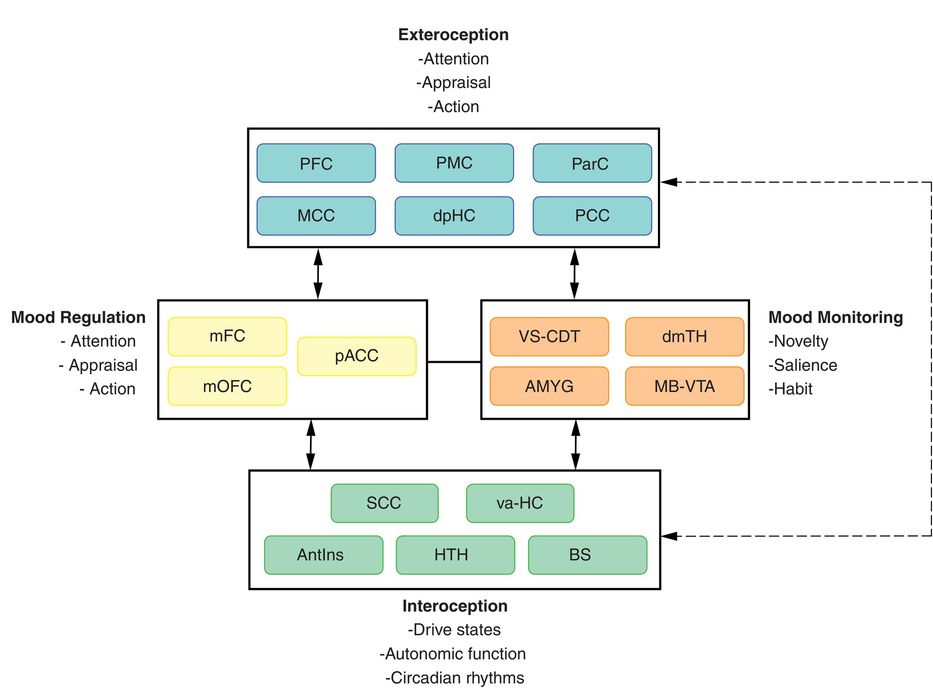

Circuit models of major psychiatric disorders proposed for DBS treatment.

Depression model, adapted from Mayberg (2009).47 Regions with known anatomical interconnections that show consistent changes across converging imaging experiments form the basis of this model. Regions are grouped into four main compartments, reflecting general behavioral dimensions of MDD and regional targets of various antidepressant treatments. Regions within a compartment all have strong anatomical connections to one another. Black arrows identify cross-compartment anatomical connections. Solid colored arrows identify putative connections between compartments mediating a specific treatment. AntIns, anterior insula; AMYG, amygdala; BS, brainstem; dmTH, dorsomedial thalamus; dpHC, dorsal–posterior hippocampus; HTH, hypothalamus; MB-VTA, midbrain–ventral tegmental area; MCC, medial cingulate cortex; mFC, medial frontal cortex; mOFC, medial orbitofrontal cortex; pACC, the perigenual area of the anterior cingulate cortex; ParC, parietal cortex; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex; PFC, prefrontal cortex; PMC, premotor cortex; va-HC, ventral–anterior hippocampus; SCC, subcallosal cingulate; VS-CDT, ventral striatum–caudate.

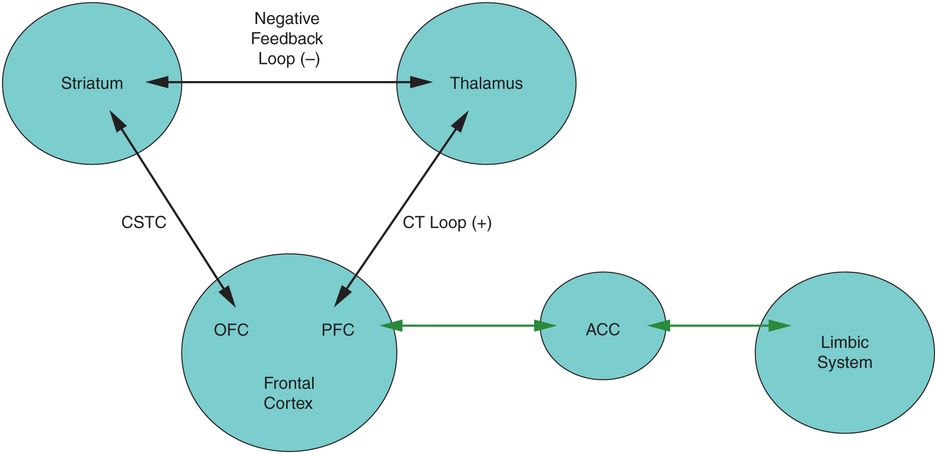

OCD model, adapted from Corse et al. (2013).17 Hypoactivity of the cortico-striatal–thalamic–cortical (CSTC) loop (between the OFC and striatum) or hyperactivity of the corticothalamic (CT) loop (between the OFC/PFC and the thalamus) may result in OCD symptoms. ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; OFC, orbitofrontal cortex; PFC, prefrontal cortex.

This remains one of the open questions for the use of DBS to treat psychiatric disorders in the early twenty-first century: understanding the anatomical targeting, clinical study design, and device programming approaches required to demonstrate the applicability of DBS as a general tool for precision neurotherapeutics. OCD provides a valuable clinical model for moving this knowledge base forward. The clearer definition of symptoms (leading to a more “pure” study population) compared to depression may help DBS for OCD clearly separate from sham control conditions. Furthermore, the relatively low prevalence of severe and treatment-resistant OCD qualified VC/VS DBS for approval via the HDE pathway, which did not require the extremely stringent randomized-controlled standard being applied for MDD. As more centers outside the academic core begin to use DBS for this indication, we will gain a much greater understanding of how DBS benefits patients in “real-world” settings.

Patient selection

Because the only currently FDA-approved indication for DBS to treat psychiatric disorders is for intractable OCD, we will confine the remainder of the discussion in this chapter to that diagnosis and its approved target, the VC/VS. At this time, DBS at any other target or at VC/VS for any other indication should be considered investigational (or compassionate-use, in very rare cases), and should be conducted only under rigorous human subjects protection and in pursuit of a well-supported neuroscientific hypothesis. Even VC/VS DBS for OCD is approved under a Humanitarian Device Exemption (HDE), an FDA classification reserved for devices where the eligible population is extremely small. As a consequence, all clinicians seeking to perform OCD DBS in the United States, even if not for research purposes, are required to register a surgical protocol with an appropriate Institutional Review Board (IRB). Practically, IRB registration provides limited oversight, and we recommend a much more rigorous oversight process, described in the following section.

Appropriate OCD patients for treatment with DBS meet three key criteria: they have severe and treatment-resistant disease, they are otherwise medically and psychiatrically stable, and there is no evidence for a surgical or psychological contraindication after a detailed search for such contraindications.

Severe and treatment-resistant OCD, rigorously defined and verified, is an absolute requirement. Clinicians should document for a prospective patient that OCD is:

(a) Present, as diagnosed with a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID) appropriate for the present DSM version. Importantly, there is no rigorous evidence for the use of DBS in other disorders with obsessive–compulsive features, such as hoarding, hair-pulling (trichotillomania), or body dysmorphic disorder.

(b) Severe, as indicated by multiple recent scores above 30 on the Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (YBOCS).25

(c) Treatment-resistant after verified and adequate trials of evidence-based treatments. We recommend the use of an Antidepressant Treatment History Form or similar (see Appendix O for examples) to collect this history. Past trials must include both pharmacological/somatic and psychotherapeutic interventions, particularly:

(1) At least three trials of serotonergic agents (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, or tricyclic) for at least three months each after achieving the maximum allowable or tolerated dose. Complete failure to tolerate an agent could substitute for a medication trial, but it would be exceptional for a patient to be completely unable to tolerate all agents.

(2) At least one of the three serotonergic trials used clomipramine, either alone or in combination with another medication. Clomipramine intolerance is acceptable if clearly documented (what dose tried, what side effects experienced). In practice, a re-trial is often appropriate before proceeding to DBS.

(3) At least one augmentation trial each with an antipsychotic medication (at maximum tolerated dose) and a long-acting benzodiazepine such as clonazepam (also at maximum tolerable dose). These augmentation trials can overlap in time with the core serotonergic agent trials.

(4) At least 20 sessions of exposure and response prevention (ERP) psychotherapy. It is critical to verify that these sessions were delivered by a practitioner with specific experience in OCD, and that the combination of ERP with medications has been specifically tried for a full 20 sessions. Adequate ERP trials also require verification that the patient gave genuine effort; we will routinely review a sample of clinicians’ notes and/or directly contact recent therapists.

Patients must be medically and psychiatrically stable to undergo DBS surgery and manage the complexities of life with an implanted brain stimulator. Stability includes:

(a) A constant psychopharmacological regimen (which may mean being drug-free) for at least six weeks. Active, ongoing medication titration can make it difficult to assess the effects of stimulator programming in the early postsurgical phase.

(b) Absence of active substance use disorder within the preceding year.

(c) Absence of poorly controlled medical problems, particularly cardiovascular or metabolic. The DBS neurosurgeon and anesthesiologist should consider the patient’s current physical health and be comfortable considering him/her as a surgical candidate.

(d) Availability of psychosocial support. Although not an absolute requirement, DBS patients often find it helpful for a family member or significant other to assist in managing interactions with the psychiatric or surgical team.

Major contraindications for psychiatric neurosurgery include ethical, medical, and psychological complications that would amplify the risk of a poor surgical outcome. These include:

(a) Cognitive impairments that prevent comprehension of the surgical risks and benefits and the ability to give informed, written consent. In general, language barriers alone do not qualify as an exclusion.

(b) Very young (under 18) or very old (over 75) patients. There are ethical limitations and a lack of evidence for the use of DBS in the former, and the benefits may not outweigh surgical risks in the latter. Age is not an absolute contraindication, but it should prompt extra levels of review, oversight, and informed consent.

(c) Current or past primary psychotic disorder, which may impair the patient’s ability to manage the device.

(d) Past bipolar mood disorder of any type, as established by structured clinical interview. Because VC/VS DBS can cause mania-like symptoms (see below), there is a substantial risk of iatrogenic mania if used in the presence of bipolar disorder. Note, however, that past mania in response to an exogenous stressor (stimulant, antidepressant treatment, etc.) is considered substance-induced mood disorder, not bipolar disorder.

(e) Past history of severe personality disorder (generally evidenced by hospitalization with a primary personality disorder diagnosis). Such patients have difficulty adhering to the complex DBS regimen.

(f) Active suicidality or a history of multiple impulsive suicide attempts.

(g) Bleeding disorder or other condition that creates elevated risk for brain hemorrhage.

(h) Structural brain abnormality, such as tumor or malformation.

(i) Active neurological disorder, such as epilepsy, parkinsonism, or dystonia. VC/VS DBS has been performed in the presence of such disorders, even with a DBS device already in place to treat a movement disorder.26 However, such use remains firmly experimental.

(j) Foreign metal body in tissue or other contraindication to the necessary preoperative imaging for DBS localization.

(k) Current pregnancy and/or being of childbearing age but not using an effective form of contraception. The risks to a fetus of anesthesia outweigh the psychiatric benefits of DBS, which can always be deferred until after parturition.

There may be reasons to overrule one of these exclusionary criteria, but this should not be done lightly or unilaterally. It should involve an interdisciplinary discussion, and ideally consultation with an expert or experts independent of the DBS team.

Surgical candidacy review

The key to successful use of DBS for psychiatric indications is a tight collaboration between clinicians from the disciplines of psychiatry, neurosurgery, and neurology, from the point of initial screening through to postoperative device programming and patient management.

As noted above, we believe that patients must have psychiatric care established outside the DBS team, and our process begins with a referral from the patient’s established outpatient psychiatrist. Initial screening involves a thorough history of the disease (onset, longitudinal course, current symptom severity) and prior treatment trials, generally collected through standardized forms (see Appendix P). The submitted information is then collated by a psychiatrist or study coordinator into a unified and coherent clinical summary. We usually find missing information during that assembly, and assembly of the final summary is usually a multiweek, iterative process. We consider psychiatry to be the best specialty for performing this initial summary, as a psychiatrist can more readily identify subtle discrepancies or concerns regarding the patient’s presentation or treatment.

The psychiatrist who received the referral and prepared the summary then presents the patient to a multispecialty Psychiatric Neurosurgery Committee. All committee members review the case, ask questions regarding elements of the history that may raise concern, and offer opinions regarding possible confounding neurological or psychiatric diagnoses. After deliberation, the presenter prepares a letter back to the referring psychiatrist. This usually contains a request for further treatment trials or further clarification on aspects of the history, even after there has been substantial investigation to prepare the initial summary. This highlights the stringency of the process; one recent paper suggests that far fewer than 1% of OCD patients will ever meet criteria for treatment with DBS.27 Even if all of the preceding criteria are met, any committee member should be able to object to proceeding with DBS treatment based on other clinical criteria, usually related to concerns about the patient’s ability to adhere to neurostimulator charging and maintenance schedules.

This formalized structure is essential, as it provides a structure for policy documents, longitudinal clinical data, and interspecialty dialogue. Further, we believe that such a committee affords valuable ethical and legal protection for the team. Even with the FDA HDE, DBS in psychiatry is often viewed through the lens of psychiatric and surgical abuses of the middle twentieth century.1,3 An organized and hospital-sanctioned committee demonstrates the legitimacy of the work by documenting a rigorous approval process and careful consideration of the patient’s best interests. Further, it ensures that a patient is only selected for treatment with DBS if there is genuine concurrence, by multiple clinicians, that he/she is capable of managing a neurostimulator and there is reason to believe that DBS therapy will lead to clinical benefit. The latter point is critical: patients referred for intervention with DBS have been living with severe and treatment-resistant mental illness for years. Such patients often have unreasonably high expectations of a favorable outcome, and committee members must support each other in pushing back against those assumptions. We believe that failure to carefully select patients and manage expectations at this early phase is likely to produce outcomes substantially worse than those reported in formal trials.

Preoperative medical evaluation and informed consent

Once the history has been clarified and the entire committee is satisfied that the patient is appropriate for treatment with DBS, the patient should meet with at least the psychiatric and surgical members of the DBS team in clinic. We frequently add a neurologic visit and/or formal neuropsychological testing, as is commonly done for movement disorder patients being considered for DBS. Although there are no reported neurologic side effects typical of VC/VS DBS in OCD, it is helpful to document the patient’s preoperative status in case questions arise. Regardless of the order of visits, a complete preoperative evaluation should include:

Physical exam with detailed neurologic examination

electrocardiogram and chest x-ray for patients over 45

Complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, blood type and screen, coagulation panel, hepatic functional panel, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level

Urinalysis, urine toxicology screen, and urine pregnancy test for female patients of childbearing age

Magnetic resonance imaging, ideally performed with gadolinium contrast and at high anatomical resolution (1 mm slice thickness). MRI both identifies surgical contraindications and provides vital planning information.

The preoperative psychiatric visit orients the patient to the implantation and programming workflow, the expected parameter-mapping procedure, and the likely time course of subsequent visits. This is usually conducted by the psychiatrist who will take primary responsibility for managing the patient’s DBS therapy after surgery. Our practice is to use this psychiatric visit as the formal point of informed consent for surgery. The preceding extensive evaluation notwithstanding, consent for treatment with DBS should be a careful process, conducted with adequate time for questions and understanding. We routinely videotape all patient consent sessions and retain the archived video as part of the medical record. The consenting physician should explicitly discuss the major risks of surgery and of an implanted medical device, as well as the chance of psychiatric decompensation (further explained below). It must be clearly elicited and documented that the patient is aware that DBS therapy may not relieve his/her symptoms and is choosing to accept substantial morbidity/mortality risk for a poorly quantified chance of benefit. For research studies, we generally use an external consent monitor, and this would be appropriate in a purely clinical setting as well.

Implantation

Aside from the details of anatomical targeting, the implantation of VC/VS DBS for OCD is identical to DBS lead implantation for movement disorders, and it should follow the surgeon’s usual process for DBS surgery. DBS leads are always placed bilaterally. At our institution, the preferred targeting is defined by a line between the midpoints of the anterior commissure (AC) and posterior commissure (PC). The VC/VS DBS target is 1–3 mm anterior to PC, 5–7 mm lateral to the AC–PC line, and 1–3 mm below the AC–PC plane. This places the deepest electrode in the ventral striatum, just below the axial plane; see Figure 11.3 for an example. Microelectrode localization is often helpful, although the target itself consists partly of white matter and is thus fairly silent from a physiological mapping standpoint. We perform intraoperative stimulation through the DBS lead after implantation but before it is fixed to the skull, at amplitudes of 2, 4, and 6 V at 135 Hz, at 90 and 150 μs, and with each electrode pair in bipolar mode (total of 24 intraoperative tests). This often produces no detectable clinical effect, either beneficial or adverse. One small study suggested a weak correlation between spontaneous smile or laughter during test stimulation and eventual response to long-term DBS, although there was no relation between the electrode that induced intraoperative effects and the patient’s final best treatment electrode.28 Rarely, stimulation produces panic-like sensations, particularly at the most ventral electrode. If this occurs, we withdraw the lead by 1.5 mm and re-test.

Surgical targeting for VC/VS DBS, from Malone et al. (2009).19 Magnetic resonance images from a representative patient showing preoperative targeting (left) and postoperative DBS lead position (right). Image distortion due to artifact from the metal components of the DBS lead causes the size of the lead to appear larger than actual.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree