Managing Young People With Depression and Comorbid Conditions

MARYANN O. HETRICK

KIRTI SAXENA

CARROLL W. HUGHESa

KEY POINTS

Depression is often comorbid with other disorders, particularly anxiety disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and disruptive behavior disorders.

Detecting comorbid conditions early in the assessment process is an important aspect of a comprehensive assessment and needs to be taken into account when planning treatment.

Principles for Treating Childhood Depression and Comorbid Disorders

Alleviate symptoms of the most severe disorder first.

Improvement in the specific symptoms of depression and the respective comorbid disorder(s) should be systematically monitored by objective measures to assess response to treatment, rather than monitoring global functioning in isolation. Measures should include multiple sources, such as clinician-, parent-, and child- or adolescent-rated forms.

The potential for suicidality should be assessed at every treatment visit, particularly when individuals present with comorbid disorders that might exacerbate the symptoms of depression or there are previous suicide attempts, impulsivity, substance abuse, and so on. Safety plans should be developed and implemented, as needed.

Patients and their parents should be advised to contact the practitioner if symptoms become more severe, suicidal ideation or suicidal gestures begin, or if medication side effects become problematic.

With the consent of legal guardians, communication should be open and frequent among different treating clinicians (e.g., psychiatrist, psychologist, school personnel, etc.) to ensure treatment integrity.

Pharmacotherapy

Begin with a single medication when possible. Then make one medication change or addition at a time and allow adequate time for response and possible dose adjustments.

If the patient shows minimal to no improvement in symptoms, and dose has been increased, a change in medication may be warranted after 4 to 8 weeks of treatment. However, if the patient appears to be responding in some fashion to the medication, remission may still be achieved by 12 weeks.

Those with residual symptoms after 12 weeks might benefit from augmentation or changing to a different treatment in order to achieve complete remission.

Patients should have more frequent visits early in the treatment. This allows the practitioner to provide psychoeducation to the family, enhance rapport, monitor changes in symptoms, identify risk for suicidality, monitor adverse effects, and adjust the dose of medications.

If side effects pose concerns, the dosage should be lowered or a different medication prescribed. Treating side effects of one medication with another medication should be avoided because it can increase the risk of drug interactions, resulting in more side effects or decreased benefit (see Chapter 14).

If the use of multiple medications is clinically warranted (e.g., to treat the comorbidities), clinicians should be knowledgeable and vigilant about potential negative interaction effects.

Psychotherapy

Goals should be collaboratively established and agreed upon with the patient and his or her parents.

Goals should be clear and measurable to allow for effective monitoring of improvement.

Therapeutic interventions should have specific symptom targets/issues.

In case of failure to respond to initial treatment, reassessment is essential.

aCarroll Hughes receives research support and is a consultant to Biobehavioral Diagnostics, Inc. Neither Maryann Hetrick nor Kirti Saxena has any competing interests to report.

Introduction

Although major depressive disorder (MDD) may occur in isolation, oftentimes that is not the case. It is estimated that 40% to 90% of children and adolescents diagnosed with MDD also have one comorbid psychiatric disorder, and 20% to 40% have two or more, which compromise further their ability to function.1,2 According to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,1 anxiety disorders are the most common disorders that present with depression, whereas other disorders, such as ADHD3,4,5 or other disruptive behavior disorders, occur less frequently. More specifically, approximately 30% to 80% of depressed youth are also diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, whereas 10% to 80% have a comorbid disruptive behavior disorder. Although the developmental trajectory of comorbid conditions depend on several individual factors, it appears that certain types of psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety disorders or ADHD, are more likely to develop before symptoms of MDD.2 Additionally, base rates of specific comorbid conditions vary according to developmental phases of life (e.g., childhood versus adolescence).6 Other disorders comorbid with depression include eating disorders, pervasive developmental disorders (including Asperger syndrome) (see Chapter 22), and substance abuse (see Chapter 18), but they occur less frequently.

Establishing the timeline of onset of the respective disorders is an important part of the assessment and differential diagnostic process. For example, anxiety symptoms occurring only within a depressive episode are not considered to meet DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, as opposed to onset before the MDD. In terms of developmental age, the rate of comorbid MDD and separation anxiety disorder is high in childhood, whereas the rates of comorbid MDD and conduct disorder, social phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder are higher in adolescence. Given the differential rates of comorbidity by age, practitioners are advised to consider base rates of co-occurring disorders when treating depressed youth and assessing potential comorbid conditions. Additionally, practitioners should be familiar with the overlap of symptoms among these disorders because this knowledge can aid in differential diagnosis and accurate identification of comorbid diagnoses. Table 17.1 presents a summary of the symptom clusters for various psychiatric disorders, which shows how easy it can be to mistake one disorder for another in a quick, cursory review of presenting complaints if symptoms for individual disorders are not reviewed carefully.7 It would still be worse to stop the clinical interview after confirming a single diagnosis and to begin treatment without considering the possibility of other comorbid disorders that may warrant a different management. Finally, one would be remiss not to consider possible substance abuse or medical conditions that are contributing to or causing the symptom profile that needs to be addressed first.

TABLE 17.1 A LIST OF POSSIBLE OVERLAPPING SYMPTOMS IN DIFFERENT CHILDHOOD PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Accurate diagnosis is critical, so a method for reviewing all of the major childhood disorders systematically is essential and always part of good practice. Recognizing that it is not economically feasible for the majority of practitioners to use one of the structured diagnostic interviews, a diagnostic checklist that reviews the symptom profile for each disorder should be used as a minimum. There are some computerized diagnostic assessments (e.g., Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents [DICA]) and behavioral problem summaries (e.g., Behavioral Assessment System for Children [BASC]) commercially available that can be completed by the parent and/or older child prior to the assessment visit. This also applies to disorder-specific self-reports.8 They not only help clarify the differential diagnosis but place current symptoms in focus, which is important for an ongoing objective assessment of treatment outcome.

When a child or adolescent presents with MDD and a comorbid condition, clinicians are advised to consider both disorders when devising a treatment plan and to focus initially on the more severe. Additionally, it is best to consider biopsychosocial factors, which warrant clinical attention and may guide treatment planning. Concern has been raised that common life events (e.g., a setback in school for some reason, breaking up with boyfriend or girlfriend, injury preventing continuing participation in a sport or other physical activity, etc.) associated with short-term depressive symptoms are sometimes too hastily described as MDD and would be better characterized as time-limited dysphoria not meriting antidepressant medication. Instead of initiating medication, “watchful waiting” can be a useful strategy.9 Further, specific treatment approaches differ depending on the type of comorbid diagnosis, which diagnosis is the primary or most severe, and the age of the patient (e.g., child versus adolescent). The specific therapies chosen and the order in which they are implemented depend on the combination of disorders, given that different therapies are more effective for certain disorders. It has increasingly become good practice to combine pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy for optimal treatment.10 A discussion of assessment methods and treatment modalities for different comorbid disorders (i.e., anxiety disorders, ADHD, and disruptive behavior disorders) follows.

With regard to pharmacotherapy, treatment of comorbid disorders with MDD has become more complicated because of concerns that risk for suicidal ideation may increase for a minority of those treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)11 when compared with placebo (see Chapters 7 and 14 for more details).

DEPRESSION AND COMORBID ANXIETY

As noted earlier, the probability of treating a depressed child or adolescent with a comorbid anxiety disorder is higher than that of any other childhood comorbid psychiatric disorder. As such, the presence of anxiety disorders should be screened carefully in depressed children and adolescents to ensure the most appropriate treatment is implemented. Each of the 14 different types of anxiety disorder included in DSM-IV has a unique set of symptoms, and interventions can differ substantially, emphasizing the importance of careful assessment of the full spectrum of possible types of anxiety. Fortunately, pharmacotherapy for anxiety is frequently similar to that for depression, as discussed later. Comorbid anxiety may be detected using rating scales in conjunction with a thorough clinical interview (see Chapter 3). However, not all rating scales are equally valid and reliable. Pavuluri and Birmaher12 evaluated child and adolescent rating scales for depression and anxiety to guide their use; Table 17.2 provides a brief summary. Pavuluri and Birmaher underscore the importance of using clinician as well as parent reports and child self-reports to ensure a thorough assessment of symptoms.

They specifically recommend the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS), the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC), or the Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED).

They specifically recommend the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS), the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC), or the Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED).

TABLE 17.2 SUMMARY OF SOME AVAILABLE ANXIETY RATING SCALES | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

As with many disorders, a multimodal treatment is recommended, which may consist of medication, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and involvement of the parents and family. However, the specific treatment components and the timing/order in which each component is implemented depend on many factors, such as the nature and severity of the symptoms. For instance, if a child or adolescent has marked dysfunction as a part of severe depression, he or she may experience difficulty engaging in the CBT process2 because of lack of energy, difficulty concentrating, and pervasive negative cognitions. In such cases, it is recommended that treatment of depression via medication be implemented first, with the aim of alleviating the severity of depressive symptoms.2 Once depressive symptoms improve, the child or adolescent will be more likely to engage in the CBT, increasing the likelihood of success.

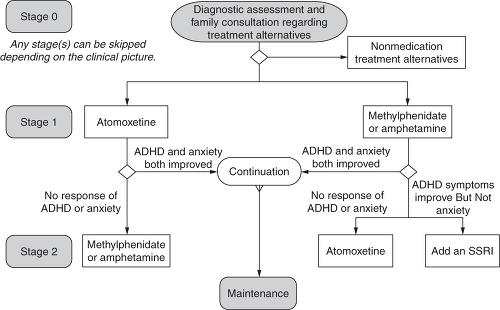

Medication algorithms have been developed to guide physicians treating individuals with various disorders, such as comorbid MDD and ADHD or ADHD and anxiety.13,14 Figure 17.1 illustrates the algorithmic approach for childhood anxiety and ADHD as comorbid disorders. Although a medication algorithm has been developed for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder15 and for ADHD with comorbid anxiety, one for the treatment of comorbid depression and anxiety disorders is yet to be developed. It is conceivable that such an algorithm would combine the features of Figures 17.1 and Figure 6.1 (see Chapter 6) using the hierarchical approach of addressing the most severe disorder first.

The results of double-blind, placebo-controlled studies provide empirical evidence for guidelines for the treatment of MDD with anxiety disorders. These studies have shown that SSRIs are an effective treatment for anxiety and depression, making them the ideal medication to use when the two disorders present simultaneously.2 When anxiety symptoms are moderate or severe, impairment makes participation in psychotherapy difficult, or psychotherapy results in partial response, treatment with medication is recommended.16,17 In particular, recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have compared the short-term effectiveness of SSRIs with placebo, finding that SSRIs are an effective treatment for generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, seasonal affective disorder,18,19,20,21 social anxiety,22 selective mutism with social phobia,23 and obsessive compulsive disorder.24,25,26 Table 17.3 lists

a summary of the best studied medication interventions with recommended doses. SSRIs are well tolerated by children and adolescents with only mild and transient side effects, such as gastrointestinal symptoms, increased motor activity, headaches, and insomnia. Disinhibition is much less frequent (see Chapter 14). It is important to obtain family history of bipolar illness along with bipolar (I or II) as a possible disorder in the child as a part of assessment before initiation of SSRIs.

a summary of the best studied medication interventions with recommended doses. SSRIs are well tolerated by children and adolescents with only mild and transient side effects, such as gastrointestinal symptoms, increased motor activity, headaches, and insomnia. Disinhibition is much less frequent (see Chapter 14). It is important to obtain family history of bipolar illness along with bipolar (I or II) as a possible disorder in the child as a part of assessment before initiation of SSRIs.

TABLE 17.3 MOST FREQUENTLY RECOMMENDED MEDICATIONS FOR DEPRESSION WITH COMORBID DISORDERS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree