Mania and Mixed States

Alan C. Swann

Mania is a behavioral syndrome that can be life threatening or life ruining. Many medical conditions can cause or contribute to mania (1,2). Bipolar disorder is defined as the cause of primary mania. Successful management of mania requires identification of causal and contributory factors and of complications (medical, social, and legal), and definitive steps toward stabilization of behavior. Some aspects of treatment are specific to the cause of the manic episode; others are more generally related to severe agitation associated with the manic syndrome.

PRESENTING CLINICAL FEATURES

Classic mania would appear easy to recognize. Mania can also occur in the context of other psychiatric disturbances, including mixed states in which syndromal depression is present (3). Further, mania can present diagnostic challenges because it can have many medical causes in addition to bipolar disorder, and because it can lead to medical complications (1,2). Finally, even when the presence of acute mania is recognized, it can be clinically challenging to treat the patient effectively while dealing with the many problems that mania can generate.

The Manic Syndrome

Components of the Manic State

More than a disturbance of affect, mania is a pervasive syndrome encompassing potentially drastic changes in content and form of thought, physical activity, and behavior. Table 18.1 summarizes the components of mania.

TABLE 18.1 Components of the Manic Syndrome | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

Diagnostic Criteria for a Manic Episode, and their Relevance

Table 18.2 shows the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for a manic episode (4). The symptomatic criteria mean, essentially, that the patient is experiencing a pervasive disturbance of affect, thought, physical function, and behavior. The duration and severity requirements improve the reliability of diagnosis. Criteria for hypomania are more problematic. Recent data suggest that a duration requirement of 2 days may have more validity than the current 4 days (5).

TABLE 18.2 Diagnostic Criteria for a Manic Episode | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

Common Presentations of Mania

Classic Mania

Classic mania is generally defined as a manic episode without prominent depressive or psychotic features. These episodes also are considered not to be associated with rapid changes to other mood states. The patient may exhibit increased goal-directed hyperactivity, euphoric affect, grandiosity, rapid speech that is hard to interrupt, and racing thoughts. Even the most infectiously euphoric patient, however, is likely to become irritable in the face of delay or interference.

Psychotic Manic States

About half of manic episodes are associated with delusions or hallucinations or both (6,7). These episodes generally entail more severe functional impairment than do episodes without psychotic features (8). Delusions and hallucinations are usually mood congruent, but can also be mood incongruent. Mood-incongruent delusions are associated with more severe, longer-term psychosocial impairment (9).

Mixed Manic States

Manic episodes can have prominent depressive features. The DSM-IV-TR defines a mixed state as a manic episode that also meets the diagnostic criteria of a major depressive episode for at least 7 days (4). Clinically, mixed presentations cover a broader range than this and can entail a gamut of combined depressive and manic symptom severity(10,11,12). Further, severity of depression or mania can fluctuate during the episode (13). Mixed episodes are challenging for the following reasons:

Patients susceptible to mixed episodes usually have a severe course of illness with greater likelihood of substance use disorders, anxiety disorders, trauma, neurologic insults, and medical disorders compared with patients without mixed episodes (3,14).

The combination of mania, with its activation and impulsivity, and depression, with its hopelessness, is dangerous, with potential for suicide and violent behavior (15,16).

Mood lability (13) and severe agitation (12)in mixed states can make these patients

unpredictable and difficult to manage clinically, and underscore the misery that these patients may experience.

Contexts of Manic Episodes: Medical, Social, Legal

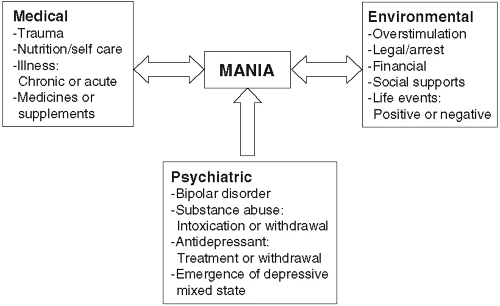

Patients in manic episodes are often in trouble. Mania engenders interpersonal conflict, poorly considered financial and legal decisions, and indiscretions (19). Further, patients in manic episodes tend to neglect their health. Figure 18.1 summarizes the manner in which mania can produce clinical and social consequences that complicate its emergency treatment.

Bipolar Disorder and Secondary Mania

Mania is a nonspecific syndrome with many medical and pharmacologic causes (1,2). Table 18.3 briefly summarizes some conditions that can contribute to manic episodes. Patients with bipolar disorder are more susceptible to mania of any cause, primary or secondary, than are individuals who do not have bipolar disorder (2). This especially holds for patients susceptible to mixed states (14). Mania is a prominent potential cause of catatonia, especially if other medical or psychiatric disorders are also present (20,21). Therefore, the clinician must be alert for both contributors to and effects of manic episodes in bipolar disorder. Mental status examination alone is not likely to distinguish episodes with organic features (22). Figure 18.1 summarizes this schematically.

TABLE 18.3 Some Factors That Can Cause or Contribute to Manic Syndromes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Behavioral and Interpersonal Problems in Mania: The “Manic Game”

Individuals who are experiencing manic episodes present interpersonal challenges to the emergency clinician. Cognitive disorganization, the characteristic cognitive distortions of mania, and disinhibited goal-directed hyperactivity make it difficult to interview manic patients (23). The patient is likely to construct a wall of words that reduces, rather than facilitates, communication. In addition, patients who are manic exhibit a constellation of interpersonal maneuvers that can lead to escalation of their symptoms and can be severely disruptive (24). These interpersonal maneuvers, called “the manic game” by Janowsky et al. (24), include manipulation of self-esteem by flattery and devaluation, splitting, testing limits, eliciting anger, and projecting responsibility, and stem

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree