Chapter 14 Memory problems

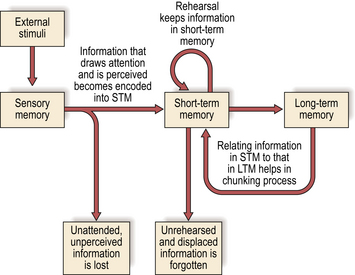

We are all familiar with lapses of memory – not being able to put a name to a face; forgetting to keep an appointment; and poor recall during an exam. Psychologists have learned a great deal about the process of memory in the past 100 years through both laboratory-based experiments and by studying patients with brain damage resulting in unique forms of memory loss. Although a very simplified view, Figure 1 is a useful summary of a widely held basic model of memory. Items are initially held in a short-term store and whether they become permanently represented in a long-term memory (LTM) store will depend on a host of factors such as how important and interesting they are, and whether we engage in active rehearsal strategies to encode items into permanent or LTM. There are also many different divisions of LTM, in particular a distinction between declarative and procedural memory (i.e. between memory for facts and autobiographical episodes and memory for skills and other cognitive operations).

Stages of memory

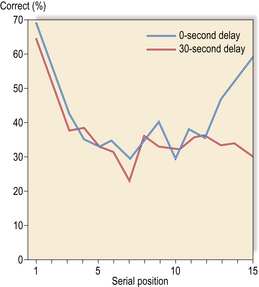

If we listen to a list of unrelated words read out to us, and then are required to recall the words immediately, items presented either first or last are better remembered than those in the middle. This better recall for the more recent items is because we are retrieving them directly from the short-term memory store. If we were to delay recall of the word list by 30 seconds, then this recency effect disappears (Fig. 2).