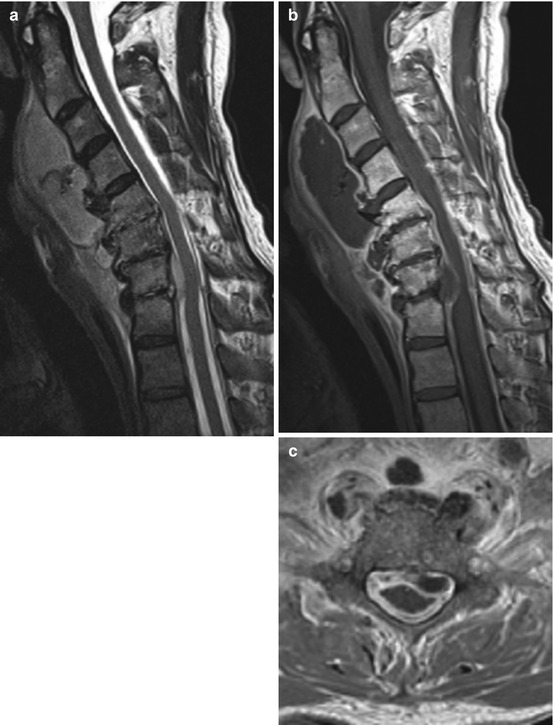

Fig. 13.1

Bacterial spinal meningitis. Patient with bacterial spinal meningitis (S. pneumoniae) extended from cranial meningitis. Contrast-enhanced T1WI shows diffuse smooth enhancement of the conus medullaris and equina cauda (sagittal, a); the equina cauda is slightly thickened (sagittal and axial, a and b)

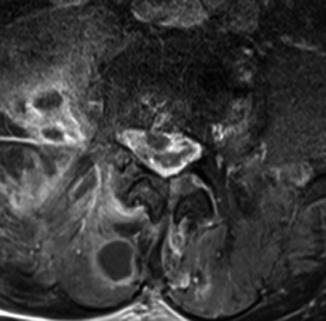

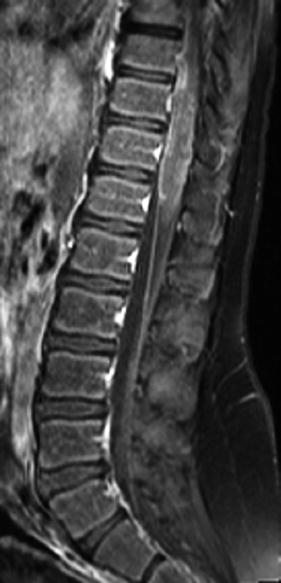

Fig. 13.2

Spinal meningitis. Patient with extensive spinal meningitis as a consequence of spondylodiscitis (C5/6, 6/7, and C7/Th1, a and b); other complications shown include prevertebral and epidural abscesses. T2WI (sagittal, a) shows pachymeningeal thickening; abscesses show intermediate signal. Intervertebral spaces C5/6, 6/7, and C7/Th1 and adjacent vertebra show hyperintense signal caused by inflammatory edema. Contrast-enhanced T1WI (sagittal and axial, b and c) shows massive enhancement of pachy- and leptomeningeal structures and rim-enhancing abscesses. There is diffuse enhancement of the surrounding soft tissue as well (axial)

13.2.2 Subdural Abscess/Empyema

Collections of pus in the potential subdural spinal space between the dura and arachnoid are rare, and only less than 100 cases of spinal subdural empyema extending over multiple spinal levels have been reported in the literature. Patients are usually of higher age (60–70 years), and women are more often affected than men (2:1). Etiologically, subdural abscesses/empyemas usually result from invasion of pathogens due to surgical procedures or trauma or from a continuous spread from adjacent inflammatory processes. Less common subdural abscess/empyema is caused by hematogenous spread or idiopathically. The most common pathogens are Streptococci and Staphylococcus aureus.

Spinal subdural abscesses/empyemas are most commonly located in the lumbar region, followed by the cervical region. Clinically, patients present with signs of meningeal irritation, increased intracranial pressure, fever, and back pain. The symptom onset is usually rapid and sometimes fulminant. Due to its potential rapid compressive effect, spinal subdural abscess/empyema represents an extreme medical and neurosurgical emergency. Treatment of choice is surgical drainage followed by appropriate antibiotic therapy; dexamethasone should be added postsurgically.

Imaging (Fig. 13.3): On MRI or CT, thin intradural extramedullary fluid collection with potential gas accompanied by diffuse subdural thickening should be considered subdural abscess/empyema. Spinal cord displacement, impingement, and edema might be seen also. T2WI shows hyperintense fluid; its presence might be suggested by mass effect on the spinal cord and obliterated subarachnoid space. Contrast-enhanced T1WI shows heterogeneous, diffuse subdural enhancement and hypointense, rim-enhancing fluid collection. Axial imaging confirms subdural localization.

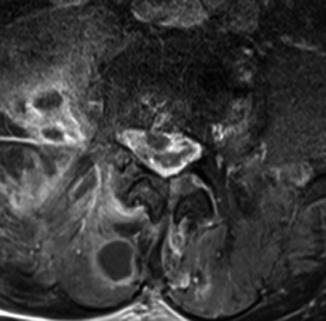

Fig. 13.3

Subdural abscess. Contrast-enhanced T1WI shows neurosurgically confirmed subdural abscess with circumscript intraspinal hypointense fluid collection and massive enhancement of the meninges. The adjacent subarachnoid space is compressed. Note further abscesses and diffuse enhancement of the surrounding soft tissue (right psoas muscle and autochthonous back muscles)

13.2.3 Tuberculous Meningitis

Tuberculous meningitis of the spine can present as primary tuberculous radiculomyelitis. More frequently, it is secondary to cranial meningitis or vertebral involvement. Although tuberculous meningitis is the least frequent presentation of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, it is the most severe form in terms of mortality and morbidity. The so-called atypical mycobacteria may present identically in terms of clinical and radiological manifestation; pathogens include M. avium complex (most common atypical form), M. kansasii, M. peregrinum, M. scrofulaceum, M. gordonae, and M. fortuitum. Clinical symptoms include fever, back pain, radicular symptoms, focal neurological deficits, and fatigue. In contrast to typical bacterial meningitis of acute onset, symptoms of tuberculous meningitis usually manifest chronically and fluctuate in terms of severity and location.

Imaging (Figs. 13.4 and 13.5): The typical imaging findings of tuberculous meningitis are similar to those of typical bacterial meningitis. However, involvement of the pachymeninges is more common. There are frequent nodular enhancement and nerve root thickening, caused by acute edematous swelling or chronic adhesions. On T2WI, the arachnoid surrounding the spinal cord and nerve roots can be thickened, and an irregular contour of the dural sac might be seen. The spinal cord can exhibit focal inflammatory myelopathy with increased signal and swelling. On T1WI, an increased signal of the CSF might be seen which is caused by high protein content. On contrast-enhanced T1WI, mycobacteriosis typically presents with diffuse enhancement of the meninges, including the posterior fossa. Less frequently, focal nodular enhancement of the pachy- and leptomeningeal structures can be observed. The CSF can enhance homogeneously. If nodular thickening is extensive, it can be seen on CT myelography.

Fig. 13.4

Tuberculous meningitis. Patient with spinal tuberculous meningitis extending from cranial manifestation. Contrast-enhanced T1WI (a, c) shows extensive nodular enhancement of the leptomeninges (including cerebral basal meningitis) surrounding the spinal cord and massive thickening and enhancement of nerve roots (b and c)

Fig. 13.5

Atypical mycobacteriosis. Patient with atypical mycobacteriosis (M. fortuitum). T2WI (sagittal, a) shows slight deformation of the upper cervical spinal cord and a short dilation of the central canal; circumscript myelopathy is visible at level C6. Furthermore, small hypointense nodules of the meninges are seen at levels C5 and C6. Contrast-enhanced T1WI (sagittal, b) shows diffuse and nodular leptomeningeal enhancement

13.2.4 Neurosarcoidosis

Neurosarcoidosis is a rare manifestation of sarcoidosis (5–15 %) that can affect the spinal meninges. If present, meningeal involvement is usually secondary to spinal cord involvement. Less commonly, meningeal involvement can occur as the primary spinal presentation (10–20 %). Sarcoidosis typically presents between the third and fourth decades of life; the overall disease prevalence of neurosarcoidosis is estimated at 4 per 100,000. African Americans are affected three to four times more frequently than Caucasians. Pathologically, sarcoidosis is characterized by noncaseating granulomatous inflammation of unknown origin. Elevated angiotensin converting enzyme and other systemic manifestations help with diagnosis. When neurosarcoidosis occurs without other organ manifestations, diagnosis is problematic, and biopsy of neural tissue remains the gold standard of diagnosis. The typical signs of meningitis aside, clinical symptoms depend on the anatomic location and can range from asymptomatic manifestation (10 %) to focal neurological signs and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Acute meningitis due to neurosarcoidosis responds well to systemic corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants including azathioprine and methotrexate; however, chronic meningitis is usually persistent and requires long-term therapy.

Imaging (Fig. 13.6): MRI shows leptomeningeal and nerve root enhancement, mimicking spinal bacterial or tuberculous meningitis, and swelling of the spinal cord with myelopathic edema. T2WI might reveal nodular hypointense thickening of the arachnoid and fusiform hyperintense swelling of the spinal cord close by. On contrast-enhanced T1WI, nodular leptomeningeal enhancement is typically found. This can include the cranial basilar meninges and the nerve roots. The adjacent spinal cord can show focal fusiform hypointense swelling and focal enhancement.

Fig. 13.6

Neurosarcoidosis. Contrast-enhanced, fat-saturated T1WI shows nodular enhancement of leptomeningeal structures including the cauda equina. Fusiform swelling and irregular enhancement of the conus medullaris reveal spinal cord involvement

13.2.5 Guillain-Barré Syndrome

The incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) ranges between 1 and 2 per 100,000. Men are more frequently affected than women (2:1). Most patients had suffered from upper respiratory tract infection or diarrhea some weeks before, and GBS is suspected to be caused by an autoimmune response affecting the peripheral nerves and their roots. The most common infectious agent associated with GBS is Campylobacter jejuni, a pathogen causing diarrhea. GBS is classified into two subtypes: acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and acute motor axonal neuropathy. Initially, typical clinical symptoms include ascending paralysis beginning with progressive symmetric paraparesis with hypo- or areflexia, distal paresthesia, and, possibly, urinary retention. During progression, meningeal, muscular, radicular, and arthralgic pain, respiratory insufficiency, life-threatening cardiac arrhythmia, and psychiatric symptoms may occur. Diagnosis is more likely in the presence of albuminocytologic dissociation. Patients should be kept under hospital observation until there is no more evidence for disease progression. Patients should be monitored regarding cardiac and pulmonary dysfunction. Treatment includes intravenous immune globulin or plasma exchange, if patients are not able to walk unassisted, while corticosteroids are not effective.

Imaging (Fig. 13.7): Contrast-enhanced T1WI may demonstrate diffuse enhancement of conus medullaris and cauda equina including leptomeningeal structures, and nerve root thickening might be present.

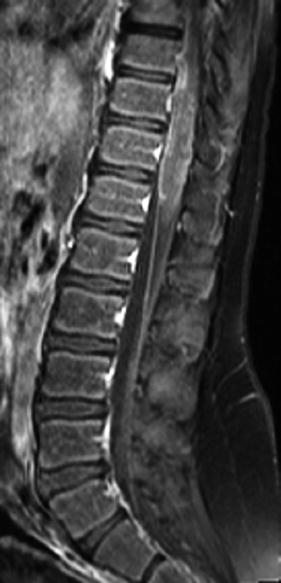

Fig. 13.7

Guillain-Barré syndrome. Patient with GBS showing massive thickening and enhancement of nerve roots (c, d) and cauda equina (b), extending from the cervical to sacral spinal canal on contrast-enhanced T1WI (sagittal a, b and axial c, d)

13.3 Neoplastic Meningeosis

Neoplastic meningeosis is the result of malignant cells seeding into the leptomeninges. It occurs in 1–5 % of patients with solid tumors (Meningeosis carcinomatosa), in 5–15 % of patients with leucemia (Meningeosis leucemica) or lymphoma (Meningeosis lymphomatosa), and in 1–2 % of patients with primary brain tumors (glioblastoma, medulloblastoma/PNET, ependymoma, etc.).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree