CHAPTER 60 Meningioma Metastasis

INTRODUCTION

Metastasis is a process by which cancer spreads from its primary site to a distant location in the body.1 In ancient Greek the word metastasis means “translocation from one place to another” [Greek: meta, “to change” and histanai, “place”]. Such spread in the body is rarely encountered in meningiomas and the determinants of this rare phenomenon are still unknown almost a century after the first reported case.2–5

HISTORY

In 1926, Towne6 described the first case, in which the parasagittal meningioma in a 54-year-old man invaded the superior longitudinal sinus and other dural sinuses. The tumor spread by direct continuity to the superior vena cava via the left internal jugular vein. Since then approximately 100 case reports and small case series have been published, and these have established metastasis as a rare but significant process in both malignant and benign meningiomas.2–5

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Extraneural metastases are uncommon in central nervous system (CNS) tumors. In their analysis of Annual of the Pathological Autopsy Cases in Japan, Nakamura and colleagues7 concluded that the frequency of extracranial metastasis was 3.8% when of all brain tumors were considered. In this study extracranial metastases were most commonly found in primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNET), meningioma, glioblastoma multiforme, and ependymoma.7 Another study conducted on 1011 children who were operated for intracranial tumors found an incidence of 0.98% with medulloblastoma, germ cell tumors, ependymoma, and atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor (ATRT) with decreasing order of frequency.8 The relatively high incidence of metastasis in meningiomas when compared to other CNS tumors is not completely unexpected, as meningiomas arise outside the anatomic boundaries of the blood–brain barrier.3

The incidence of meningiomas in the general population has been estimated to be 2.3 per 100,000.9 They constitute 13% to 26% of all primary CNS tumors.9 Metastasis is rarely observed in meningiomas. There are only few small case series and few sporadic case reports totaling to around a hundred cases in the literature (Table 60-1). Hemangiopericytomas are excluded from this analysis.10 The incidence of metastasis is estimated to be 0.15% to 1% of all CNS meningiomas.2 Adlaka and colleagues5 analyzed 1992 primary intracranial meningiomas seen at the Mayo Clinic from 1972 through 1994 and identified three patients (0.15%) with documented extracranial metastasis. Enam and colleagues,3 in their analysis of 396 patients who initially presented with intracranial meningiomas, found the incidence for metastasis to be 0.76% when all meningiomas were considered and 42.8% when malignant (anaplastic) meningiomas were considered. No metastasis was observed in benign meningiomas in this cohort, which contained 5.8% atypical and 1.8% malignant meningiomas. Perry and colleagues, in their analysis of 116 malignant meningiomas, found that 3 (11%) of 27 frankly anaplastic meningiomas had metastasized. In this series metastasis accounted for the first malignant diagnosis in 2 (1.7%) of 116 cases and one of these cases had otherwise benign histology. Prayson4 reported an 26% incidence of metastasis in 23 patients with malignant meningiomas. All these reports support an increasing incidence of metastasis with increasing grade.

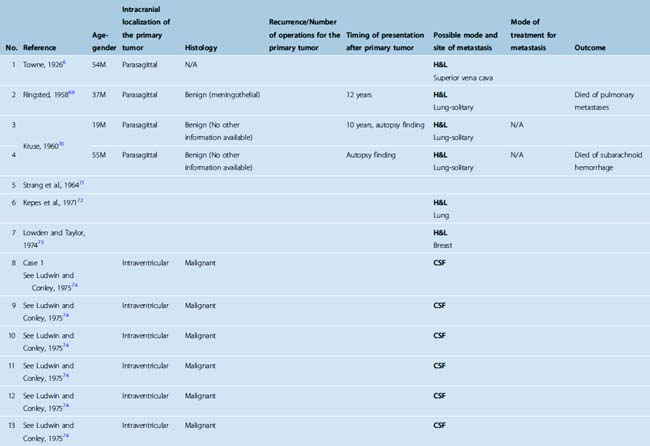

TABLE 60-1 Metastatic meningiomas (malignant cases appear in black, benign cases in blue, and unknown in green)

Metastatic meningiomas are more commonly seen in men (61.4%; see Table 60-1). This is in contrast with the overall female preponderance in primary disease.11 Most meningiomas occur in the middle and old age group, and metastatic cases are not an exception.10 The median age of the patients in literature was 47.5 (age range 6 months–87 years; see Table 60-1).

PATHOGENESIS–PATHOLOGY

Four mechanisms have been suggested for the occurrence meningioma at an extracranial site: (1) primary intracranial meningiomas with extracranial invasion, (2) distant metastasis from an intracranial lesion, (3) origin from arachnoid cells within cranial nerve sheaths (and from tumors outside the CNS), and (4) origin from embryonic rests of arachnoid cells (in peripheral organs that form de novo meningiomas).12 Distant metastasis from an intracranial meningioma can occur through hematogenous/lymphatic metastasis, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) seeding, or iatrogenic implantation. Information on the route of metastasis was available for 91 cases in our literature analysis. The most common routes for extracranial metastasis are hematogenous and lymphatic and these were identified in 65.9% of the cases. CSF seeding was seen in 29.7% and surgical implantation in 11% of these metastasis cases (see Table 60-1).

Hematogenous or Lymphatic Extracranial Metastasis

In our literature review we found lung metastases in 45.8%, bone metastases (including spine) in 24.1%, vertebral metastases in 19.3%, intracranial metastases in 16.9%, spinal intradural metastases in 12.1%, surgical site metastases in 12.1%, pleural metastases in 10.8%, lymph node metastases in 10.8%, intra-abdominal metastases in 9.6%, and at other sites (orbit, paranasal sinuses, thymus, parotid gland, heart and peripheral nerves) in 10.8% of the patients. Previous reports indicated that lungs and the pleura are the most common sites (60%), followed by liver and other abdominal viscera (34%), lymph nodes (especially cervical and mediastinal), vertebrae (11%), and other bones.3,11,13,14 Metastatic lesions in kidneys, urinary bladder, thyroid, breast, thymus, heart, skin, vulva, adrenal gland, and ocular fundus are reported but rarely encountered.15–17 Only 13% of the cases are reported to bear more than three metastases.18

There are 38 cases of meningioma metastases to the lung (see Table 60-1). Information on histology was present in 30 of these cases: 73.3% of these were benign, and 26.7% were malignant meningiomas; 3.3% of these had presented with a benign intracranial meningioma but had a malignant meningioma diagnosis in the metastasis. Information on the number of metastases was available in 22 cases, half of whom had solitary and half multiple metastases. Pleural metastases occur less frequently than lung metastases.18–25 In our analysis we identified pleural metastases in 23.7% of cases who had lung metastases. It should be kept in mind that meningiomas can be seen as primary tumors in the lung. This entity is exceedingly rare, and only 11 cases have been reported so far.5 Primary pulmonary meningiomas may be benign or malignant, solitary or multiple.26,27

It has been hypothesized that in meningiomas invading dural venous sinuses or cerebral veins, tumor cells may enter the systemic circulation.17,28 Drummond and colleagues11 stated that metastasis is more commonly observed in parasagittal and falcine meningiomas but the incidence must be very low considering the high percentage of meningiomas with venous sinus involvement that do not metastasize. In his well known study, Simpson29 observed infiltration of the dural sinuses in 34 (14%) of 246 intracranial meningiomas but extracranial metastatic lesions were detected in only one. After such systemic dissemination, tumor cells may enter the pulmonary circulation or the vertebral venous plexus. Rarely long bone metastases is seen in meningiomas, which suggests that metastasis through an arterial route may also be possible.30–32

Metastasis is commonly observed in malignant meningiomas and the rare metastases of histologically benign meningiomas typically occur after surgery. Several authors therefore have noted that surgery may predispose to systemic metastasis by allowing tumor cells to access the bloodstream and lymphatic circulation.3,33,34 This is supported by the fact that most metastases have been reported in patients who have undergone multiple operations for the cranial tumor recurrences. Russel and Rubinstein34 indicated that 70% of metastases are found in patients who have undergone at least one craniotomy. A notable finding was that 75% of these operated cases had invasion of a venous sinus.28 However, in few cases metastases were not associated with previous surgery.35,36

CSF Seeding

Although meningiomas are thought to arise from arachnoid cap cells and are naturally exposed to CSF, seeding through the CSF is even more rare than hematogenous spread.17,37–39 We identified 27 cases of meningiomas with metastatic spread through the CSF (see Table 60-1). Of these cases, 57.7% were malignant, 3.95% atypical, and 38.5% benign. In two cases (7.9%) the primary tumor was of benign histopathology but the metastatic lesion was diagnosed as a malignant meningioma. In most of the cases the primary tumor was an intraventricular meningioma (88.2% of the cases with known location of the primary). There was a very slight female predominance (43.8% men and 56.2% women). Chamberlain and Glantz40 reported the largest series of eight patients with CSF seeding confirmed by cytology, which interestingly included extraneural metastases in five (62.5%) cases. This particular cohort consisted of eight benign meningiomas that have received extensive treatment including multiple surgeries in all patients (median, two surgeries; range, one to five surgeries), external beam fractionated radiotherapy in seven (87.5%) patients (median dose, 54 grays [Gy]), stereotactic radiotherapy in five (62.5%) patients (median dose, 18 Gy), and chemotherapy in all patients (hydroxyurea administered for 3–9 months [median, 6 months]). As demonstrated in this small cohort and other case reports, the diagnosis of CSF spread can be supported by cytology.40,41 Otherwise, seeding through the CSF may be difficult to distinguish from multifocality, which should be suspected especially in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2).

Local Iatrogenic Seeding

Iatrogenic seeding, a.k.a. “implantation metastasis,” is thought to be caused by unintended implantation of tumor cells during surgery.42 The significance of iatrogenic seeding during surgery is not known because it is very rarely observed. As indicated in the preceding text, surgical manipulation may be a source of tumor spread and this may also be true for iatrogenic seeding. Most surgeons have experienced meningioma recurrence at the bone or subcutaneous tissue at the surgical flap, especially in patients with repeated craniotomies. We came across only 10 cases iatrogenic spread of meningiomas.5,21,32,39,40,42–46 In eight of these cases the metastases were in the head,5,21,32,39,40,42,43,45 in one case at the abdominal incision,43 and one case occurred in the temporalis muscle.46 In one patient recurrence was seen at the abdominal donor site of an autologous fat graft, which was placed into the orbit in a case of malignant sphenoid wing meningioma.43

Determinants or the mechanism of such a surgical spread is not known. One intriguing hypothesis is the local action of growth factors known to be induced during wound healing, such as fibroblast growth factor (FGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and transforming growth factors (TGFs) may potentiate seeded tumor growth, and cause preferential tumor growth at this location but there are no clinical or experimental data to support this notion.47–50

Pathologic Correlates of Metastasis

Invasion and metastasis are generally considered to be the hallmarks of malignant behavior, and this is also true for meningiomas. In Cushing and Eisenhardt’s 1938 monograph, brain invasion was considered a sign of malignancy.51 Since then, extracranial metastasis had been referred as the strongest evidence of malignancy in meningiomas.3,34 However, accumulating evidence has indicated that this is not necessarily true. As noted in the preceding section on incidence, the risk of metastasis rises with increasing histologic grade. But when metastatic cases were analyzed it became apparent that some of these tumors had a benign histopathology and relatively better prognoses. In their analysis of 116 malignant meningiomas, Perry and colleagues37 concluded that the underlying histology was of greater prognostic significance than the fact that the tumor has metastasized. In current histopathologic classifications brain invasion alone does not sufficient for diagnosis of malignant meningioma and metastasis is considered an indicator of malignancy, but in meningiomas of any subtype.10 This is supported by cytogenetic findings indicating that metastasizing meningiomas do not necessarily have more complex genetic changes when compared to their non metastasizing counterparts.52 The histopathologic diagnosis, however, does not fully predict the biological behavior or the clinical outcome. Meningiomas that present with brain invasion have a prognosis comparable to atypical meningiomas.10 This also holds true for benign metastasizing meningiomas that fare far worse than ordinary cases.

The majority of meningiomas are benign. Malignant meningiomas constitute 1% to 2.8% of the cases.10,53 Metastasis is seen in 11% to 43% of the malignant tumors.3,37 Although less frequently seen, metastasis is also seen in intracranial meningiomas with benign histopathology. This led to the concept of “benign metastatic meningiomas.”16 We found a total of 35 histologically verified benign metastatic meningioma cases in the literature (see Table 60-1). Considering that benign meningiomas are 36 to 100 times more common than malignant meningiomas and the fact that there are comparable numbers of reports of metastasis in both benign and malignant meningiomas (malignant: benign ratio = 1.11) one can conclude that clinical presentation of metastasis is 40 to 110 times more common in malignant meningiomas. When we analyzed benign metastasizing meningiomas, we observed a male predominance, which was also the case in metastatic meningiomas in general. There was a clear predominance of parasagittal localization (72.2% of patients where the site of primary is reported).

Another possibility is that these new foci are not metastases but in fact previously undetected multifocal meningiomas. The findings of Strangl and colleagues54 who demonstrated monoclonality in half of the non-NF2–associated patients with multifocal meningiomas further supports this possibility. Whether these secondary growths in cases of benign meningiomas represent true metastases or de novo growth from ectopic embryologic remnants has yet to be proven.3 If these are in fact “real” metastases, another clinical implication would be that the benign histopathologic diagnosis in a meningioma (with the current histopathologic classification scheme) falls short of excluding metastasis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree