Mental Retardation

Fred R. Volkmar

Elisabeth M. Dykens

Robert M. Hodapp

Definition

In DSM-IV-TR (1), mental retardation (MR) is defined on the basis of three essential features: subnormal intellectual functioning, commensurate deficits in adaptive functioning, and onset before 18 years. Of these three criteria, the first two are most often discussed. Subnormal intellectual functioning is characterized by an intelligence quotient (IQ) lower than 70, based in most cases on the administration of an appropriate standardized assessment of intelligence. Deficits in adaptive skills, which involve one’s social and personal sufficiency and independence, are generally measured on instruments such as the recently re-revised Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (2) or a similar scale. DSM-IV-TR criteria for mental retardation are summarized in Table 5.1.2.1.

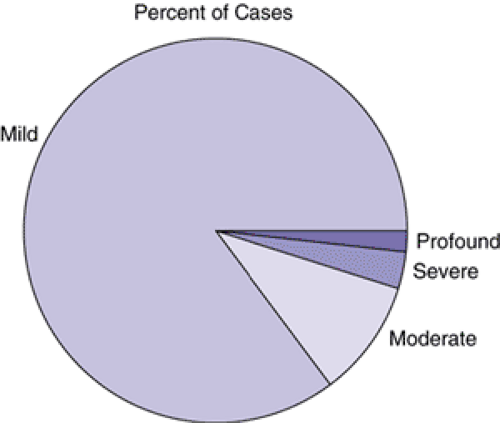

Various levels of MR are specified in the DSM-IV-TR: mild (IQ 50 to 70), moderate (IQ 35 to 49), severe (IQ 20 to 34), and profound (IQ <20). Borderline MR can be noted as a V code. Some flexibility is allowed for clinical judgment. Most persons with MR in childhood are those with mild MR (about 85% of cases); the remainder of cases comprise those with moderate (about 10%), severe (about 4%), and profound (1% to 2%) MR (Figure 5.1.2.1). In the past, the distinction was made between educable (IQ 50 to 70) and trainable (IQ <50). Although no longer commonly used, this distinction is important. Persons with mild MR often have psychiatric difficulties that are fundamentally similar (if generally more frequent) to those seen in the general population; this is not true for more severely impaired persons. Similarly, specific medical conditions associated with MR are more likely in the group with an IQ lower than 50, whereas lower socioeconomic status is more frequent in the group with mild MR (3). The proportion of persons with severe and profound MR is higher than would be expected given the normal curve, reflecting the impact of genetic disorders and severe medical problems on development (4).

The tests chosen for assessment of intellectual functioning should be appropriate to the patient, have reasonable reliability and validity, and be administered in a standardized way by appropriately trained examiners (see Chapter 4.2.4 for a discussion of psychological assessment.) Unfortunately, in some situations, the selection of an appropriate test can be difficult, such as for a very low-functioning person. Other aspects of assessment can also be problematic, such as when some modification must be made in terms of administration given the specific circumstance. Such modifications may limit the validity of the results obtained. The examiner must then make an informed decision depending on the nature of the issue at hand, for example, determination of eligibility for services versus information on levels of functioning that can guide remediation. Particularly in terms of eligibility for services, it is critical that the examiner administer the test in exactly the standardized fashion. Measures of adaptive skills are generally based on parent or caregiver report, although, in some cases, the person may be interviewed directly. In essence, the conceptual notion is that the term adaptive skills refers to the performance of day-to-day activities required for personal or social self-sufficiency.

The inclusion of adaptive skills in the definition of MR rests on the observation that some persons with IQ scores below 70 may, as adolescents or adults, have learned sufficient adaptive skills that they are able to function totally or largely independently. Technically, then, such individuals would not meet criteria for MR. This situation is more typical of persons who, as children, score in the mildly retarded range (5).

The approach to the definition of MR is fundamentally the same in the tenth edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) (6). However, the definition of MR promulgated by the American Association of Mental Retardation (AAMR)— first in its 1992 manual (7) and later (in revised form) in its 2002 manual (8)— discards the use of IQ levels in favor of a “needs-based” nosology that identifies the intensity of supports that persons require to function best within multiple adaptive domains. This definition also gives the clinician leeway to extend the upper IQ bound to 75; this seemingly small increase would actually considerably broaden the diagnostic concept of MR, potentially doubling the total number of cases (9). The AAMR definition has been much criticized and has had very little empirical support. Partly as a result, the AAMR definition (particularly its 1992 version) has not been widely used either in research (10) or in state guidelines (11).

Historical Note

Interest in MR can be traced to antiquity (12,13). Modern interest in MR began at the time of the Enlightenment and increased greatly during the nineteenth century; this emphasis occurred at the time of great social upheaval and as infant and child mortality began to decline. There was increased interest in children, in education, and in the role of experience (nurture) versus endowment (nature). The interest in the “nature–nurture problem” is exemplified in Itard’s work with Victor, a child who was thought to be wild or “feral” but who may have had autism (14,15).

Subsequently, educators such as Seguin began to develop specific educational methods for stimulating children’s development. By the latter half of the nineteenth century, many facilities had been developed for the care of persons with mental retardation. Although the initial goal of such facilities was to provide a period of treatment before the child was returned to the family, these institutions gradually became places for custodial care (12). This problem has led to a strong counterreaction in recent years and to a renewed emphasis of caring for persons with MR in their homes and communities (16).

During the nineteenth century, various distinctions were made between levels of MR by using what now would be seen as rather pejorative terms (imbecile, cretin, idiot). Originally, the etiologic basis of any such distinctions was quite limited. On one hand, there was little systematic information on intellectual functioning that could be used for purposes of

categorization. On the other, there were few known etiologic causes of MR.

categorization. On the other, there were few known etiologic causes of MR.

TABLE 5.1.2.1 DSM-IV DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR MENTAL RETARDATION | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Toward the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries, both these limitations began to be addressed. Binet developed the first test of intelligence, which was translated into English and adapted in the United States by Terman (27,18). As a model psychometric assessment instrument for many years, the Stanford-Binet test allowed much more precise characterization of levels of intellectual disability. In addition, Terman had the brilliant notion of taking the mental age, dividing it by the child’s chronological age, and multiplying this quotient by 100. The resulting IQ score allowed for comparisons across children of different ages. Although Binet had originally developed his scale to identify children who were delayed in order to help them, the IQ score quickly became the object of much study.

Faith in the IQ as a predictor variable led to several extensions. First, developmental testing began to be performed on infants and young children (19). Second, proponents of the new tests believed that, when the test was properly administered, the resulting score from an IQ test was fixed and reflected a person’s genetic endowment. This proved incorrect. In a classic study, Skeels and Dye (20) demonstrated this practically by transferring infants and young children from an orphanage to a home for the “feeble-minded” to make the children normal. This fantastic plan had been prompted by clinical observation that children in the home for the feeble-minded received considerably more stimulation than those in the orphanage. Skeels later (21) reported major differences in outcomes for these better cared-for children, both in childhood and in later adult life. By the 1940s and 1950s, there was increased awareness that the IQ score was indeed the product of both experience and endowment, and therapeutic optimism again increased for improving the functioning of children with mental retardation.

In addition to the focus on intellectual functioning, it also became apparent that the person’s capacities to engage in appropriate self-care or “adaptive” skills was a major aspect of MR. In the 1930s, the psychologist Edgar Doll developed the Vineland Social Maturity Scale in an attempt to quantify such skills. Originally revised two decades ago (22), the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales have recently been re-revised (2). The Vineland Scales, now published in several versions, continue to serve as an important tool in the assessment of children with MR. Along with lower IQs, deficits in adaptive skills are now required as part of the diagnosis of MR. In contrast to IQ, however, adaptive skills can be readily taught.

Another major line of work centers on the origin of MR syndromes. In the nineteenth century, Dr. Langdon Down reported on a syndrome (which now bears his name) that is currently recognized as being the result of a trisomy of chromosome 21. At the time of his report, Dr. Down, of course, had no notion of chromosomes. Indeed, though his theoretical understanding was fundamentally flawed, Down’s clinical observation has been remarkably robust. As time went on, more and more syndromes of MR were identified. It became clear that MR could result from a range of risk factors, including problems related to the developing fetus, and ranging from genetic factors (Down syndrome) to exposure to toxins in utero (fetal alcoholism) to maternal infections (congenital rubella). As noted subsequently, advances in genetics have led to an explosion in the recognition of such syndromes, often with a very precise understanding of their cause (3,23).

In recent years, several developments have substantially changed the approach to treatment and prevention of MR

in the United States. Beginning in the 1960s, there has been increased emphasis on the care of persons in their homes and communities. The trend toward deinstitutionalization reflects various concerns about the effects of prolonged institutionalization and has led to creation of many community services. This movement has been further stimulated by the mandate of the federal government that schools provide appropriate education for all children with disabilities, within integrated settings when possible. In the United States, many students with mental retardation are largely or entirely integrated into classrooms with typically developing age mates, although there are marked state-to-state variations (24), and the benefits of mainstreaming are the focus of some debate (25). It is clear that students with more severe disabilities are most likely to spend their school time in more restricted settings.

in the United States. Beginning in the 1960s, there has been increased emphasis on the care of persons in their homes and communities. The trend toward deinstitutionalization reflects various concerns about the effects of prolonged institutionalization and has led to creation of many community services. This movement has been further stimulated by the mandate of the federal government that schools provide appropriate education for all children with disabilities, within integrated settings when possible. In the United States, many students with mental retardation are largely or entirely integrated into classrooms with typically developing age mates, although there are marked state-to-state variations (24), and the benefits of mainstreaming are the focus of some debate (25). It is clear that students with more severe disabilities are most likely to spend their school time in more restricted settings.

One unfortunate aspect of current practice has been the often complete separation of services for those who are mentally ill from those who are mentally retarded. Although administratively useful, this approach has made provision of high-quality psychiatric care even more difficult to obtain for many persons with MR. With renewed interest in the field of “dual diagnosis” of MR and psychiatric disorders (26), we can only hope that this separation will soon be ending.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

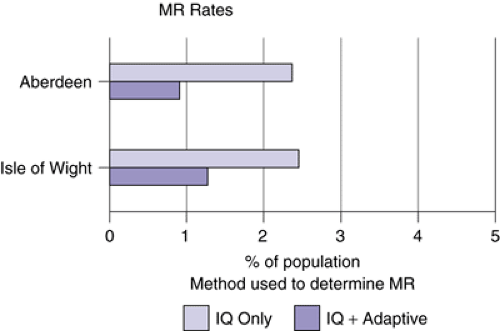

The use of both subnormal intellectual functioning and deficits in adaptive behavior in the definition of MR has important implications for epidemiology. If only the IQ criterion is used, the expectation, based on the normal curve, would be that about 2.3% of the population should exhibit the condition. This number is significantly decreased, particularly in adulthood, if the adaptive criterion is included.

For example, in the Isle of Wight study, Rutter and colleagues (27) noted that, in 9- to 11-year-old children, about 2.5% would be classified as mentally retarded if IQ were the sole criterion. But if the prevalence were based only on those receiving services, this rate would be cut almost in half (1.3%) (Figure 5.1.2.2). The drop in cases based on inclusion of IQ and adaptive skills is more common among those with mild MR; (28,29) these children (and adults) may, however, need services and support at times of stress (30,31). As children, such persons are more likely to have academic and behavioral problems (27).

Additional findings have also recently been reported from large-scale epidemiological studies (32). For individuals with severe MR, prevalence levels mostly converge on 3–4 children per 1,000; for mild MR, rates range wildly from 5.4 to 10.6 children per 1,000 (29,30). Studies also examine such correlates as gender, age, and SES. More boys than girls have mental retardation, and rates of MR are generally low in the early years, peak at around 10–14 years, and decrease slightly in the late-school years and markedly during adulthood. Individuals of lower SES and of ethnic minority groups (in several cultures) (13) also show higher than expected rates of mental retardation.

Clinical Description

Clinical Features

Associated clinical features vary depending on several factors, most important the level of retardation. Persons with severe and profound MR come to diagnosis at a younger age, more often exhibit related medical conditions, may exhibit dysmorphic features, and have a range of behavioral and psychiatric disturbances. In contrast, persons with mild MR often come to diagnosis much later (typically when academic demands become more prominent in school), are less likely to have medical conditions that could account for the MR, and usually are of normal appearance without dysmorphic features. In this latter group, although rates of psychopathology are increased relative to nondisabled populations, the range and nature of problems seen are fundamentally similar to those in normative samples (3). Persons with moderate levels of MR are intermediate between these two extremes. It is well recognized that the nature of associated psychiatric and behavioral disorders undergoes a marked shift between the mild and more severe levels of MR (33).

Associated Psychiatric and Behavioral Problems

A growing body of work focuses on psychiatric and behavioral difficulties relative to specific genetic causes (34,35). Features have been identified that are highly frequent to specific syndromes, such as hyperphagia and compulsivity in Prader-Willi syndrome (36), attentional and social problems in fragile X syndrome (37), inappropriate laughter in Angelman’s syndrome (38), the unusual cry in 5p- syndrome (39), and the self-hug in Smith-Magenis syndrome (40). In some instances, aspects of syndrome expression have even been related to the genetic features of the syndrome, such as the severity of MR in fragile X syndrome (41,42) and the type and severity of maladaptive behaviors in Prader-Willi syndrome (43,44,45). Furthermore, some of these connections between genetic disorder and behavioral outcome appear unique to a single syndrome, whereas others are “shared” between two or more syndromes (46,47,48). Thus, in some instances, features are relatively syndrome-specific, such as the unusual handwashing stereotypies of Rett syndrome (49), or the extreme hyperphagia in Prader-Willi syndrome (50). More often, however, features are shared in two or more conditions. Thus, attentional problems are frequent in fragile X, Williams, and 5p- syndromes (51,52).

Somewhat paradoxically, for many years the diagnosis of MR tended to cause clinicians and researchers to overlook the presence of associated psychiatric and behavioral problems; such difficulties, when noted at all, were assumed to be a function of the MR. This “diagnostic overshadowing” (53) remains a problem in clinical practice (54). Although more clinicians and researchers are being specifically trained to work with this population, the separation of MR and mental health

services in most states is a further obstacle to appropriate identification and treatment of mental disorders.

services in most states is a further obstacle to appropriate identification and treatment of mental disorders.

Although rates vary, as many as 25% of persons with MR may have significant psychiatric problems; these rates are much higher if persons with salient behavior disorders are included (55). Problems are invariably seen in children who present clinically (56), whereas rates are lower, from 10% to 15%, in more population-based studies, including two large-scale medical record surveys of all clients served in New York and California (57,58). Rates that fall between these two extremes, from 30% to 40%, are found in other studies based on informant checklists of behavior problems of children or adults in nonreferred samples (59).

Persons with MR experience the same range of psychiatric problems as seen in the general population (60), but prevalence rates for specific disorders vary widely. Some of this variability may be associated with different methods for determining “caseness,” with common approaches including record reviews, behavioral checklists, and, to a lesser extent, direct interviews (61,62,63,64). An additional concern is that although some researchers assess DSM- or ICD-based diagnoses, others identify maladaptive features commonly seen in the general population (inattention or sadness), whereas still others focus on a narrow range of behaviors seen primarily in persons with MR (stereotypies or self-injury) (47).

For example, rates of schizophrenia or psychosis in persons with MR range from 1% to 9% among nonreferred samples and 2.8% to 24% in referred samples. Although variable, these rates are much higher than the 0.5% to 1% of the general population with schizophrenia (1). Rates for depression vary from 1.1% to 11% across nonreferred and clinic samples of persons with MR, and rates of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder range from 7% to 15% in children with MR, a finding that contrasts with the 3% to 5% estimate among children in general (1). Patterns of psychopathology also differ across persons with or without MR. Relative to the general population, for example, people with MR are more likely to show psychosis, autism, and behavior disorders and are less apt to be diagnosed with substance abuse and affective disorders (35,36).

Assessment of Psychiatric Disorders

As researchers increasingly began to appreciate the scope of problems in persons with MR, they also developed various ways of assessing these problems. Some work has been devoted to the development of specialized rating scales and surveys; most of these measures are geared specifically for persons with MR and have well developed psychometric properties (65). Among the more widely used are the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (66), Reiss Screen (67), and Developmental Behaviour Checklist (62). A tradeoff in using these scales is that, although they are sensitive to the unique concerns of those with MR, they are not necessarily compatible with DSM or ICD psychiatric diagnoses. Further, because each scale has a different set of items and factor structures, these differences may ultimately contribute to inconsistent findings across studies (61).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree