Methods of treatment

T. P. Berney

Introduction

The presence of intellectual disability (mental retardation) affects the character of treatment in a number of ways.

1 Limited communication will hamper diagnosis so that much more has to be inferred from observable behaviour and greater weight given to the interpretation of carers.

2 Diagnosis is provisional, a therapeutic hypothesis that provides the basis for a programme of treatment that is, essentially, a therapeutic trial. There is a wide variation in individual characteristics, with intellectual disability (mental retardation) extending over an enormous range of ability, associated disabilities, aetiology, and psychopathology. Multiple pathology means that the response can be unexpected and ambiguous. For example, diminished aggression with carbamazepine may simply reflect its psychotropic effect but may also be the result of better control of unrecognized epilepsy. A well-designed behavioural milieu may produce a rapid improvement in disturbed behaviour. However, the improvement might simply reflect the effect on someone with autism of moving to a more settled, structured, and predictable environment. It may also reflect an improvement in organic disorder (such as epilepsy or gastritis) in response to a reduction in stress. The therapist has to tailor the treatment to the individual, to try to be specific as to what aspect of the disorder is being targeted and be very selective as to whom they treat.

3 Ill-defined treatment objectives often leave it unclear whether a treatment is aimed at a disorder (e.g. autism), a symptom (panic), or an associated disorder (depression or epilepsy).

4 Normal developmental change may be misattributed to a coincident treatment programme. For example, autism and epilepsy often show spontaneous improvement at about 4 years age and again in late adolescence, both times when the person is likely to be moving into new programmes. This propensity for maturational improvement, coupled with a tradition of care, has led developmental psychiatrists to have a greater therapeutic optimism for many problems, such as personality disorders, that are often considered intractable in those of normal ability.

5 Natural cycles of change can give a misleading sense of success. For example, a behavioural programme may be credited with the remission of a self-limiting episode of disorder such as depression. The true diagnosis may become clear only when it recurs and fails to respond to booster programmes.

6 There is limited evidence for the effectiveness of most treatments. Except for the behavioural therapies, most treatment is based on small series, open trials, the theoretical, and the ideal.

7 A large component of the therapeutic relationship is indirect, being with the family, carers, or professionals rather than directly with the patient. Many programmes utilize the power of the placebo effect, a dynamic that confounds scientific trials but one that should be used to its full in everyday clinical practice. Limited communication and greater dependency lead to work with the systems around the patient; many of the approaches, such as family therapy, deriving from child psychiatry.

8 The ability to consent to treatment is often underestimated. Circumstances often make it difficult for people with mental retardation to choose or refuse a particular therapy, particularly behavioural programmes and drug treatments. Their capacity to give or withhold consent should be assessed automatically and their care should fall within a legal framework that safeguards their rights and protects them from abuse.

Treatment services for people with intellectual disability (mental retardation) have two components. There is the routine support that should be available to all with intellectual disability (mental retardation). Its aim is to help people to grow up as normally as possible, offsetting the effects of their disability, and to establish the therapeutic environment. Second is the provision of treatment for individuals with disturbance; aimed at specific symptoms or disorders based on a multiaxial diagnosis(1) that includes the following:

Axis I: The nature and degree of intellectual disability (mental retardation) for, in addition to the overall developmental delay other, specific, disabilities, and abilities are often present. For example, a discrepancy between receptive and expressive language may result in someone understanding little of what is said to him while sounding falsely fluent.

Axis II: The aetiology of the retardation—there is increasing recognition of the contribution of a behavioural phenotype. Of particular note are autism and its imitators, drawing on the ubiquities of social impairment, obsessionality and communication problems, which are being teased apart.

Axis III:

• Level A: Other developmental disabilities that are associated with intellectual disability (mental retardation) such as autism, attention deficit disorder, and epilepsy,

• Level B: Psychiatric disorder—the way this is defined will define the mode of treatment. A functional analysis with antecedents, triggers, and consequences leads into a behavioural programme. A more biological label (such as psychosis) opens the door to drug treatment. They are not mutually exclusive,

• Level C: The patient’s personality—this is often unusual and it may be difficult to distinguish from a pervasive developmental disorder (see Chapter 9.2.2) which runs through Intellectual disability (mental retardation) and which, once recognized, often explains the inexplicable,

• Level D: Other disorders such as habit disorders and sexual preference disorders,

Relevant comorbid, physical conditions such as hay fever, asthma, hypothyroidism, or gastro-oesophageal disorders. Particularly important are epilepsy and the antiepileptic agents that are dealt with in detail elsewhere (see Chapters 6.2.6 and 10.5.3, respectively).

The patient’s environment which includes not just their physical surroundings but also the people and their relationships with them.

Contributory factors from the patient’s past, notably the various forms of abuse.

The therapeutic environment

Support may be provided in different ways:

Level A: General, the network of care provided for people with a intellectual disability (mental retardation) and their carers. This will include community teams, special schools, and the specialized residential placements that might be resorted to either as a short break or as a long-term home.

Level B: Specific to a particular disorder, parental support groups exist for autism, epilepsy, and specific forms of intellectual disability (mental retardation) such as Prader–Willi, Fragile X, and Cornelia de Lange syndromes.

A primary aim is to integrate people into their community as far as possible. The concept of normalization implies that services should avoid the demarcation that leads to adverse discrimination. Conversely, those with disabilities too severe or too complex for their families or standard teaching or occupational placements may fare better in specialist settings. Examples of these are as follows:

Some of those with autism, who are so distracted by the complexity of everyday life and the unpredictability of people that they need specialist environments which are well structured, predictable, and under their control.

Those with severe or intractable seizures.

Those with aggressive or disinhibited behaviour so disruptive as to block the progress of their peers.

The specialist setting encourages mutual support for people and families with similar problems; the staff gain experience; and it allows a concentration of expertise. However, it also encourages stigmatization and there is the risk that, in a group, disturbed people may copy or amplify each other’s behaviour.

The family and other carers

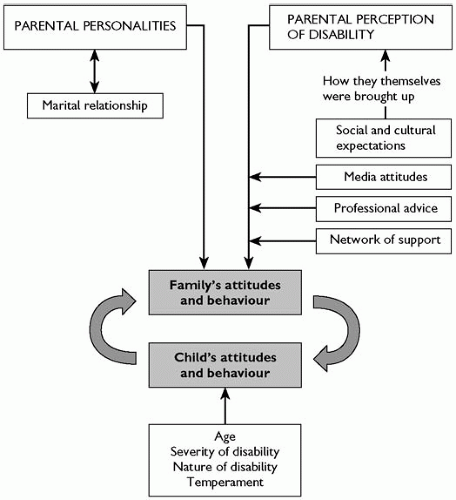

Disturbance arises in the setting of a system of care which includes not only the family but also the staff of other placements, whether day or residential, educational or occupational. Its management will depend on the way these people perceive mental retardation and its care, their attitudes deriving from both past experience and present relationships (Fig. 10.6.1). A great deal depends on the extent to which they feel supported and assured in their roles, as much by each other as by the available system of care. For example, a mother or a teacher who is told frequently that, whatever it was that went wrong, it was her fault, is unlikely to cope confidently.

Disability and disturbance both hinder normal developmental experience; the child’s atypical response spoiling the carers’ efforts to learn parenting skills and leaving them demoralized or deskilled. They may need formal teaching in such skills as how to engage socially with the child, to play with them, to give clear and understandable instructions, and how to divert rather than confront. Disturbance may reflect boredom and be reduced simply by increasing the amount and variety of activities. Any approach must take a broad view, for carers have to work together comfortably enough to be consistent over time. A treatment programme may have to address the relationship between the carers as well as their needs. This may be sufficient in itself, improvement in the patient following an overall improvement in functioning in the family, school, or residential placement. There has been a growth in the conscious application of a systemic approach to work in this field.(2)

Education

This forms the core of any treatment programme, the individual getting formal instruction in the skills which others acquire in passing. Teaching and training are lifelong processes, invoking teacher–student relationships, and take place within a structured framework, essential for those students who have difficulty in understanding their environments. The difficulty is to gauge the degree of structure required: too much and the relationship risks becoming a battle about control, easily turning into trench warfare; too little and the student is distracted and learns little. It is a balance that shifts over time, promoting the student’s self-control and autonomy.

(a) Independence and self-help skills

These include the basic skills of everyday life, such as feeding, dressing, or managing stairs or, at a higher level, the use of public transport, how to care for clothes, shop, and budget. Acquiring these, gives a sense of achievement and confidence as well as of increased independence.

(b) Communication skills

The frustration of living in an uncomprehending world frequently contributes to disturbance as the person falls back on various forms of attention seeking or violent behaviour to get their message across. Easier and more effective means of communication may range from simple gestures (e.g. pulling at the trousers to show the need for toileting), through a system of pointing to symbols or pictures, to complex signing which can convey abstract concepts such as emotional states. Language may be verbal or non-verbal and both modalities are taught simultaneously, reinforcing each other so that a course in signing can improve speech. Whatever the system used, it depends on, and will be limited by, the extent to which those around can understand it.

(c) Social and sexual relationships

People are vulnerable to exploitation until they learn the distinction between an acquaintance and a friend. Relationships become complicated by sexual behaviour, hedged around with cultural rules which vary between families making it an especially difficult area to teach and therefore tempting to ignore. Occasionally sexual arousal drives disturbance in someone for whom masturbation is inefficient, physically damaging, unlearned, or forbidden. Wider discussion can bring out strongly held beliefs and family conflicts which had been unsuspected or denied until then. This may lead on to other areas requiring resolution, such as whether a person with intellectual disability (mental retardation) should have a sexual relationship, marry, or have children.

Out-of-home placement

As described earlier, a move out of the home can be seen either as part of the wider programme of support and social d evelopment or else as part of the treatment of a specific disorder: the distinction is often blurred.

(a) Support

Short breaks allow individuals and their families some relief from the uninterrupted intimacy of care. They also widen social networks and pave the way towards the eventual departure from home, something that is ideally planned as part of an increasing, adult autonomy. Frequently however, this is left until there is a crisis, for example when the person’s behaviour or dependency has outstripped their family’s resources, too often the result of parental infirmity or death. At this point the unfortunate individual may find themselves in a series of short break (or even treatment) placements until something long-term can be arranged.

Placement for educational needs (e.g. in a residential school or college) becomes necessary where the person’s disabilities (e.g. autism or intractable epilepsy) require specialist skills and settings. It can also be a compromise with a parent who, unable to care for their child themselves, will not accept more standard forms of social care.

(b) Treatment

The threshold for admission for assessment and treatment will depend on the extent of the supportive service available in the community and is often:

1 For the treatment of more complex disorders such as epilepsy or psychosis.

2 For the assessment of disturbance where it is difficult to disentangle the relative contributions of innate from environmental factors. For example, a patient’s behaviour may be amplified by an exasperated or exhausted family, particularly where disturbed nights have left them short of sleep. This sets off a secondary, self-perpetuating cycle of disturbance involving the whole house which makes it impossible to discern the underlying, primary disturbance. The cycle may only be interrupted by changing the patient’s circumstances, either by moving staff into the home or by moving the patient out.

3 For the management of behavioural disturbance where:

The carers are unable to cope—the more frequent reasons include:

marital disharmony

the carer’s inability to manage others simultaneously, for example single parents who have several children or a home with several disturbed children

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree