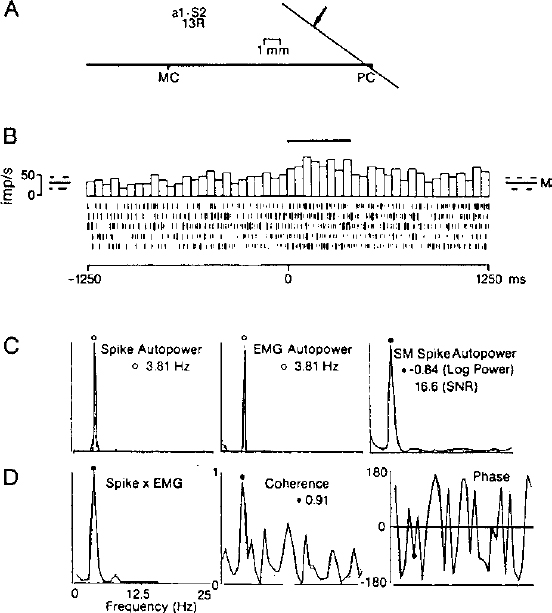

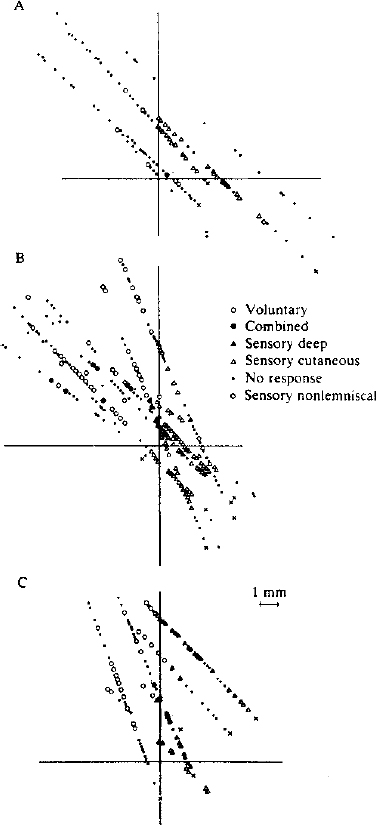

4 In the modern era, thalamic lesions for the treatment of movement disorders have been made in the ventral nuclear group of the thalamus. The nuclei in the ventral nuclear group, from anterior to posterior, are the pallidal relay nucleus (ventral oral, Vo), the cerebellar relay nucleus (ventral intermediate, Vim), and the principal somatic sensory nucleus (ventral caudal, Vc) according to Hassler’s classification.1–3 Hassler’s clinical experience suggested that the anterior portion of Vo, or ventral oral anterior (Voa), was a better target for rigidity, whereas the ventral oral posterior (Vop) was better for the relief of tremor. An area posterior to Vop was later found to have a rhythmic bursting activity close to the frequency of tremor based on microelectrode recordings.4 The nucleus in this location, Vim, became the target of choice for tremor of all types. Over the past 10 years, thalamotomy has been progressively displaced by implantation of a deep brain stimulating electrode in Vim (Vim-DBS).5 Also during this time period, Laitinen et al6 reexamined Leksell’s posteroventral pallidotomy in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. The results of Laitinen’s experience and the demonstration, in animal models, that lesions in the basal ganglia can improve all of the cardinal motor signs in Parkinson’s disease led to a renewed interest in pallidotomy.7 Finally, the recognition of drug-related complications of L-dopa therapy (dyskinesias and fluctuations) have allowed for a resurgence in the pallidum as a target.8,9 More recently, pallidotomy has been displaced by implantation of deep brain stimulating electrodes in the internal segment of the globus pallidus (GPi-DBS).5 We review the techniques of physiologic localization of the sites for lesioning and implantation of deep brain stimulating electrodes in Vim and in GPi for the treatment of movement disorders. Microelectrode, semimicroelectrode, and macroelectrode techniques for recording and stimulation are reviewed. Microelectrode recording provides the highest resolution picture of the target site at a cost of increased time to locate the target. Along with the methods for these procedures, we will discuss the data from single-cell and field potential recordings in the various thalamic and basal ganglia structures. Radiologic targeting can be used to determine the location of the anterior commissure (AC) and posterior commissure (PC) by ventriculography, MRI, and computed tomography (CT) scans. We determine the laterality of the target from a fast inversion recovery (IR) MR sequence. For targeting the thalamus, we also determine the position of the capsule and the medial dorsal (MD) nucleus as a large, dorsal, periventricular, thalamic, high-intensity signal on the IR scan (Lenz, Cell, Bryant, unpublished observations). Because the MD forms the medial boundary of Vim and Vop, the center of Vim is midway between the lateral border of MD and the medial border of the capsule.10 This central plane is matched to the closest sagittal section of the atlas. At our institution, a grid showing the location of the commissures is overlaid with a scaled clear plastic sagittal atlas section appropriate to the laterality of the trajectory.10 In this way, the nuclear locations predicted radiographically in that patient are displayed in the coordinates of the Leksell frame. The first microelectrode trajectories target Vc in this plane; physiological observations are recorded on the grid. Alternative approaches to targeting Vim from the AC–PC line include the geometric construction for approximating nuclear location as described by Guiot.11,12 Coordinates derived relative to the AC–PC line can be used in targeting Vc: 14 mm lateral, 3 mm anterior to PC, and 2 mm above the AC–PC line. Targeting can also be performed by fusion techniques,13 or by programs displaying atlas maps transformed either to match the AC–PC line14 or to match the AC–PC line and other structures, such as the margins of the third ventricle or the internal capsule.15 For targeting the pallidum, Starr et al16 studied 51 consecutive patients using an IR MR sequence, which enhances gray-white tissue contrast, allowing for visualization of GPi and its borders. While the anterior–posterior coordinate (Y) referenced the AC–PC line at the midcommissural point, the lateral (X) and vertical (Z) points were determined by direct visualization of the GPi boundaries. They measured the X coordinate 4 mm medial to the external accessory lamina between GPi and the external segment of the globus pallidus (GPe), and the Z coordinate targeted the superolateral edge of the optic tract (OT). By using this technique, Starr et al were able to maximize information obtained during the first microelectrode track. They averaged a 5.9 mm run through GPi and identified OT in 66% of the cases. To target GPi, we utilize the following coordinates based on the AC–PC line: 20 mm lateral (females) and 21 mm lateral (males), 3 mm anterior to the midcommissural line, and 3 mm below the AC–PC line. A study of 50 patients receiving pallidotomy that compared the initial MRI-derived coordinates based on the AC–PC line with that of the final target determined by microelectrode mapping of GPi demonstrated that the final lesion was more posterior and lateral to the image-derived target.17 The final lesion overlapped with the initial target less than half of the time.17 The different thalamic and pallidal nuclei can be identified on the basis of their electrophysiological properties. These properties are defined in terms of spontaneous activity, neuronal response to passive and active movements, and sensory responses to natural or electrical stimulation. Physiological localization has been performed by stimulation with a macroelectrode (impedance < 1000 Ohms), by stimulation and recording with a semimicroelectrode (impedance < 100 kOhms), or by stimulation and recording with a microelectrode (impedance > 500 kOhms). Microelectrodes for physiological monitoring and recording are designed to isolate single-action potentials.18–20 The electrode must be durable to withstand microstimulation, which degrades the insulation. These characteristics are achieved by constructing electrodes from a platinum-iridium alloy or from tungsten, producing a tapered tip, and insulating with glass.18,20–24 The electrode impedance is usually8 greater than 500 kOhms.18,19 A high impedance microelectrode is required to isolate single units at the high density of neurons found in Vc, Vim, and GPi.25 Passing current through the electrode during microstimulation will degrade insulation and lower impedance, which decreases the noise but makes it harder to isolate single units. The assembled electrode is attached to a hydraulic microdrive and mounted on the stereotaxic frame. Some microdrive systems incorporate a coarse drive so that overlying structures can be traversed quickly. The tip is then retracted into a protective cylindrical housing, while the whole assembly is advanced to a new depth.8 The microdrive may then be used from this new depth for detailed exploration of deeper structures. Another option is to use the microdrive throughout the trajectory by advancing it each time it reaches the end of its traverse.25 The signal from the microelectrode is amplified and filtered. Multiple neuronal discharges of various sizes may be seen on an oscilloscope and heard by use of an audio monitor. The “all or none” principle of neuronal discharge provides that an action potential signal of constant shape and amplitude will be produced from any one neuron. Therefore, a window discriminator may be utilized to isolate individual neuronal firing activity. The analog signal may be stored for later analysis. In addition to recording, microstimulation of subcortical structures through the microelectrode may be employed in physiological localization. Current may be delivered through the same electrode that is used for recording by disconnecting it from the preamplifier and connecting it to the output of a current-isolation stimulator. To minimize damage to the electrode tip, microstimulation is delivered in biphasic, square wave pulse trains of 0.1 to 0.3 msec pulses for durations of up to 10 sec at a frequency of 300 Hz.26 The current used in stimulation determines the amount of local current spread. Stimulation in Vc will evoke somatic sensations.27 Stimulation in Vim may alter the ongoing tremor28 or dystonia,29 whereas stimulation in GPi may also alter tremor or cause visual responses and muscle contractions.8,9 Semimicroelectode recordings are performed using microelectrodes with impedances of less than 100 kOhms. The semimicroelectrode signal is often amplified against a concentric ring electrode that is located on a radius of 0.4 mm around the microelectrode.12,30,31 Bipolar stimulation has been used through a concentric ring electrode alone or in combination with recording through a semimicroelectrode or with recording of scalp EEG.32–34 Macrostimulation through a low-impedance electrode (impedance often less than 1000 Ohms) can reliably identify the capsule by stimulation-evoked tetanic contraction of skeletal muscle at low threshold.32,33 Stimulation of intralaminar nuclei, medial to Vc or Vim, may evoke the recruiting response in the scalp EEG—long-latency, high-voltage, negative waves occurring over much of the cortex at the frequency of stimulation (usually less than 10 Hz).2,35 A recruiting response localized over the precentral cortex has been described in response to stimulation of Vim.36 In Vim, the target area can be identified by a macrostimulation-evoked increase or decrease in the amplitude of tremor.33 Although macrostimulation in Vc evokes paresthesias, similar sensations can be evoked by stimulation in Vim.33 Therefore, recording of responses to tactile stimulation localizes Vc more accurately.32 In GPi, macrostimulation can evoke muscle contractions from activation of the internal capsule as one moves posterior to the target. These responses can be found superior and posterior to sites where visual evoked responses are recorded.9 Currently, macrostimulation is commonly used in conjunction with semimicroelectrode recordings. Cells responding to sensory stimulation in small, well-defined, receptive fields are found in Vc.37 Some have described a mediolateral somatotopy within Vc19,37 proceeding from representation of oral structures medially to leg laterally. Cells anterior to the cutaneous core of Vc in the anterior dorsal cap of Vc and cells in Vim have been found that respond to joint movement and squeezing of muscles and tendons but not to manipulation of skin deformed by these stimuli (deep sensory cells). The mediolateral somatotopy of Vim parallels that of Vc, so that the deep sensory representation of the wrist is often anterior to the cutaneous sensory representation of the digits (Fig. 4–1). In Vim and Vop, Raeva38 has shown thalamic neuronal firing that was correlated with movement in response to commands, the active phase of movement, and the state of maximal muscle contraction. A large percentage of neuronal activity demonstrated statistical changes in the rate of firing related to active movement (voluntary cells).39,40 The movement-related activity of most cells in Vim and Vop is preferentially related to the execution of particular movements with a somatotopy parallel to that of the cutaneous core of Vc. Some neurons respond both to active movement and to somatosensory stimulation (combined cells).39,41 Combined cells fire in response to passive movements of a joint and in advance of active movements of the same joint. The sensory cells are found in Vc, and thus are located posterior to the cells with responses during active movement, as shown in Figure 4–1. FIGURE 4–1 Relative locations of cells identified by functional category from microelectrode studies during thalamotomy for tremor. The results have been pooled from planes in several patients where the majority of cells had activity related to hand and wrist movements. The horizontal line represents the anterior commissure–posterior commissure (AC–PC) line. The vertical line represents the anterior–posterior position of the most anterior cell responding to sensory stimulation. Therefore, the principal sensory nucleus Vc is to the right of the vertical, and the cerebellar relay Vim is to the left. Each x marks the site where the last somatic action potential was recorded along that trajectory. (With permission from Lenz FA, Kwan H, Dostrovsky JO, Tasker RR, Murphy JT, Lenz YE. Single unit analysis of the human ventral thalamic nuclear group: Activity correlated with movement. Brain. 1990;113:1795–1821.) Cells in Vc, Vim, and Vop often exhibit activity at about the frequency of tremor. Correlations between thalamic neuronal activity and tremor have been suggested previously by visual or auditory inspection.19,42–44 Quantitative analysis techniques have allowed clearer demonstration of correlation between thalamic neuronal firing and EMG activity during tremor,45,46 as shown in Figure 4–2. The surgical target is among cells with deep receptive fields and with tremor-related activity and among sites where stimulation effects tremor. During thalamotomy, lesions are made 2 to 3 mm anterior to the anterior border of Vc and 3 mm above the AC–PC line. Vim-DBS electrodes are implanted 3 to 4 mm anterior to the anterior border of Vc, approximately at the border of Vim and Vop. Insight into globus pallidum physiology for human stereotactic surgery comes from nonhuman primate studies.47–53 Studies in the model of MPTP-induced parkinsonism have also demonstrated characteristic changes in basal ganglia neuronal firing.54–56 More recently, microstimulation and recording during pallidotomy for parkinsonism have helped define human basal ganglia pathophysiology.57,58 The knowledge gained from nonhuman primate studies also serves to identify anatomic sites during pallidotomy. In subcortical recordings for pallidotomy, neuronal activity from striatum, GPi, and GPe may be distinguished by noting their firing characteristics, as shown in Figure 4–3.8,9 In general, the striatal cells fire spontaneously at a low frequency (< 1 Hz)8 and may cease firing after introduction of the microelectrode. Two populations of neuronal activity are found in GPe: pause cells (80–90%) that exhibit a higher frequency discharge pattern (50 ± 21 Hz) broken by intermittent pauses and burst cells (10–20%) that exhibit a lower frequency discharge pattern (18 ± 12 Hz) with the irregular occurrence of high-frequency bursts.8 After exiting GPe and prior to entering GPi, there is a marked decrease in activity representing the lamina between GPe and GPi. A constant, high-frequency firing pattern (82 ± 24 Hz) is encountered upon entering GPi.8 Many cells in GPi respond to active or passive movements, as shown in Figure 4–4, and an internal somatopy can be identified with a medial representation of leg movements and a lateral representation of arm movements. Border cells are encountered between pallidal segments with a regular firing pattern of 30 to 40 Hz and are thought to represent aberrant neurons of the nucleus basalis.8,9 Currently, pallidal lesioning and stimulation electrodes target the same area, the posterolateral portion of GPi, which represents the sensorimotor region.59 The mediolateral position is in the sagittal plane, where cells respond to sensory stimulation of the arm and leg, and the tip lies 2 mm above the OT and 3 mm anterior to the capsule. Semimicroelectrode recordings12,21,31,60 reveal patterns of neuronal activity parallel to those of microelectrode recordings. Vc can be identified by a high level of neuronal activity and by responses to tactile stimulation. As with the microelectrode, recording responses are usually evoked from stimulation of lips and fingers with a mediolateral somatotopy, as described above.60–63 Median or tibial nerve evoked potentials are characterized by a large positive deflection34,64; these are maximal in Vc, although such evoked potentials can be recorded for a distance around Vc.65,66 An example is the P15 wave recorded at the scalp and in Vc after stimulation of the median nerve.18,67 Vim, and perhaps Vop, can be identified by the presence of responses to stimulation of deep structures (e.g., squeezing tendons) or movement of joints.22,42,44 Phasic tremor frequency activity can also be recorded in Vim and, to a lesser extent, in Vop.68–74 Vim may also be identified by median or tibial nerve evoked potentials, which are characterized by an initial negative deflection that inverts as the electrode traverses posteriorly into Vc, as shown in Figure 4–5.12,34,65,75 Triphasic potentials are recorded in Vim following peripheral nerve stimulation with the latencies of P1 and N1 decreasing and the amplitude of the waves increasing as the semimicroelectrode approaches the target.75 No evoked potentials are recorded in Vim with stimulation of skin afferents, suggesting a separation of sensory and motor modalities within the thalamus.75 It has been reported that Vop may also be identified by spindles, an EEG pattern characterized by a 7 to 10/sec rhythm, with increases and decreases in amplitude that occur over many seconds.12

Microelectrode Techniques: Single-Cell and Field Potential Recordings

IRA M. GARONZIK, SHINJI OHARA, SHERWIN E. HUA, AND FREDERICK A. LENZ

Methods

Radiologic Localization

Physiologic Localization

Physiological Localization: Microelectrode Localization

Physiological Localization: Macrostimulation and Semimicroelectrode Localization

Microelectrode Recordings in Thalamic Nuclei

Microelectrode Recordings in the Globus Pallidas

Macrostimulation and/or Semimicroelectrode Recordings in the Thalamus

Neupsy Key

Fastest Neupsy Insight Engine