4 Microsurgery in the Cerebellopontine Angle

General Concepts

General Concepts

Preoperative Considerations (Decision-Making)

Preoperative Considerations (Decision-Making)

Neuroanesthesiologic Considerations

Neuroanesthesiologic Considerations

Operating Room Set-Up

Operating Room Set-Up

Patient Position

Patient Position

Approach

Approach

General Concepts

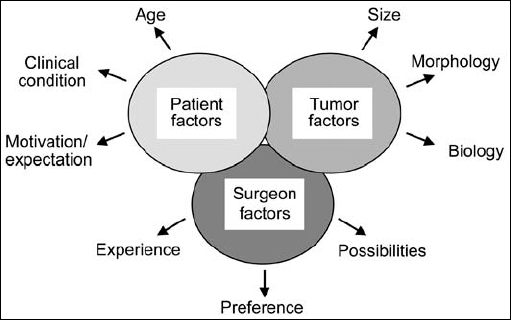

Microsurgical resection, radiosurgery, or a “wait-and-see” policy are the three accepted options that are possible in managing acoustic neurinomas. Deciding which of these is the best choice in the individual case is becoming more difficult, as increasing information becomes available about the natural history of the condition and as long-term follow-up data for radiosurgery accumulate. In addition to classic parameters such as surgical mortality, total tumor removal, and control of tumor size, considerations regarding facial nerve morbidity and preservation of hearing have become increasingly important aspects of the decision-making process. As if this were not enough, other parameters also need to be taken seriously into account in modern neurosurgery. There is the “surgeon factor,” taking the individual surgeon’s experience and track record into account; there is also the “patient factor,” involving patient’s age, general clinical condition, treatment goals, and expectations of treatment. Underlying all of this, of course, there is the “tumor factor”: the tumor itself has to be taken into account, including the anatomical, morphological, and biological parameters. The aim of this chapter is to present simple algorithms, providing simple management plans for decision-making, in which all of the factors mentioned above are included. Both treatment options—microsurgery and radiosurgery—indisputably provide excellent results. A “wait-and-see” policy is certainly preferable in some cases, however. There are justifications for each of the options, and in most cases these are indicated in the algorithms.

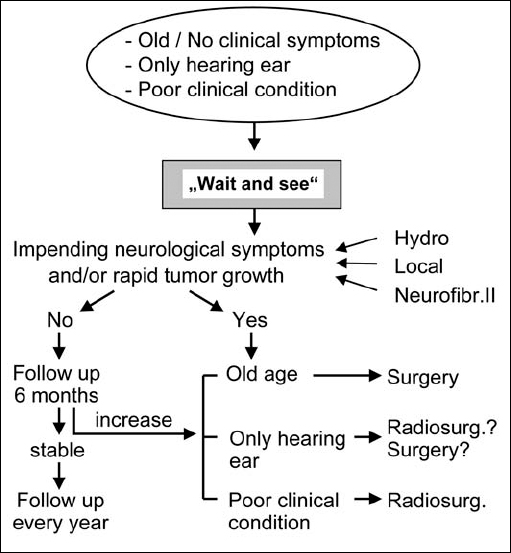

Treatment: Yes or No? (Fig. 4.1)

Fig. 4.1 The three different groups of factors affecting decision-making. The “surgeon factors” involve three main points. Firstly, there is the operating surgeon’s level of experience; secondly, his or her personal preference for one or the other form of treatment; and thirdly, what possibilities the surgeon may already have at his or her disposal. On the other hand, there are the “patient factors.” This group of parameters includes of course the patient’s age, general clinical condition, and expectations regarding treatment. A third major group of factors—the “tumor factors,” also have to be taken into account. These include typical morphological parameters, such as tumor size (grades I to IV), recurrent tumor, or special morphological situations such as type 2 neurofibromatosis and hydrocephalus.

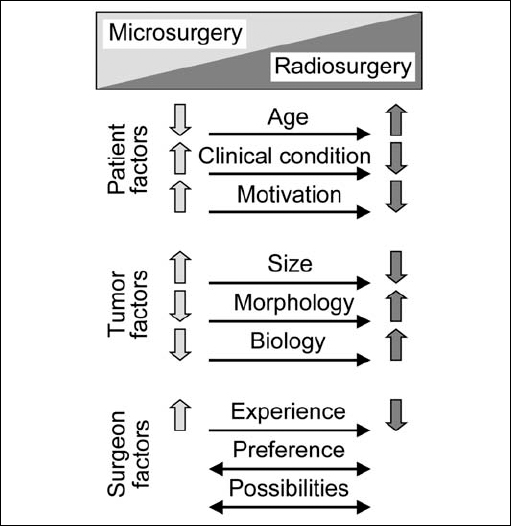

Microsurgery versus Radiosurgery (Fig. 4.2)

Fig. 4.2 In contrast to open surgery, the aim in radiosurgery for acoustic neurinomas is not to remove tumor tissue but to arrest further tumor growth. The effects of radiation take time to develop, and the results of treatment can be difficult to assess on neuroimaging. In general, there are currently no clearly defined rules regarding the choice between microsurgery and radiosurgery in treating these tumors. The decision on which is the best in the individual patient is influenced by the three major factors described in Fig. 4.1.

Preoperative Considerations (Decision-Making)

Although microsurgical removal was previously regarded as the treatment of choice, particularly in case of small neurinomas, this view has now become controversial. Since the establishment of radiosurgery as a treatment option in acoustic neurinomas. The decision has become much more complicated and uncertain both for the surgeon and the patient, despite the large numbers of publications that have appeared in recent years on the topic. The focus in contemporary publications is largely on the outcomes of radiosurgical options, which are increasingly being used as an alternative to open surgery.

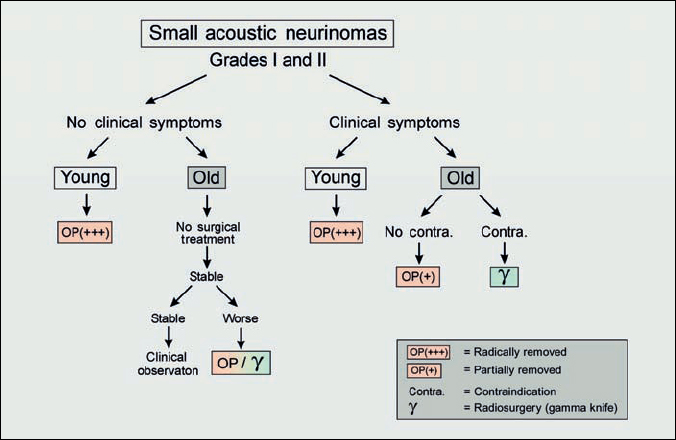

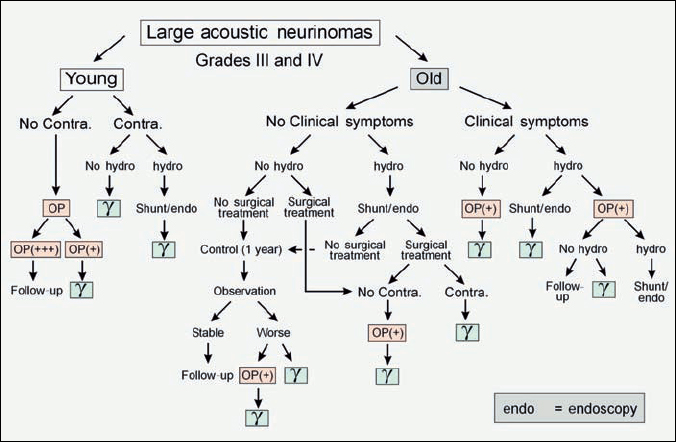

Figures 4.3 and 4.4 provide a simple algorithm for decision-making. It is reasonable, given certain assumptions, to create a simple management plan that offers clinically proven support in the choice between microsurgery, radiosurgery, or waiting and rescanning. We prefer to provide patients with full information about their situation and the nature of the pathology, as well as all the treatment options, and to discuss this with them in detail. To give patients added confidence in their decisions, we encourage them to obtain a second opinion from another well-experienced surgeon.

Fig. 4.3 Small acoustic neurinomas are defined as grade I and grade II. Nowadays, particularly as a result of earlier detection with improved magnetic resonance imaging (three-dimensional spin echo sequences), this group of tumors is increasing in number. As we know that the signs and symptoms of the tumor correlate directly with the size of the tumor, these patients generally have good hearing and no neurological symptoms. When one is dealing with small acoustic tumors, the importance of the growth rate should be borne in mind. The growth rate has been shown to be highly unpredictable. Some tumors will show no change over many years; 6 % actually decrease in size without any treatment, while some can increase in diameter by up to 20 mm per year. The range usually reported is 1–10 mm per year.

Fig. 4.4 Large acoustic neurinomas are defined as grades III and IV. Because of the size of the tumor, more signs and symptoms may occur, and these have to be taken into account when creating a treatment algorithm. The management plan in such cases is therefore more complex, but can be followed in the same way as in Fig. 4.3.

Acoustic Neurinomas in the Only Hearing Ear

In general, if the clinical situation remains stable (i.e., there is no significant change in hearing or other symptoms), we try to wait as long as possible. We prefer to wait and rescan. The follow-up is organized at short intervals, with frequent neuro-otological examinations (every 3 months) and magnetic resonance examinations (every 6 months). These patients are also encouraged to enter special programs to learn other means of communication, such as lip-reading. If hearing starts to deteriorate, or the tumor size increases in younger patients, we prefer to operate. Our approach of choice is a retromastoid one with careful tumor debulking, with an attempt being made to preserve hearing. If the patient’s motivation to have open surgery is low, radiosurgery is an option, depending on the size of the tumor (less than 2.5 cm). However, it should be remembered in these cases that radiosurgery is not without complications—complete hearing loss is also possible, as well as cranial nerve deficits or associated hydrocephalus. In patients with type 2 neurofibromatosis who are treated with radiosurgery, the failure rate appears to be higher, with early reports describing growth in about 15–20% of cases after radiosurgery. However, this difficult decision has to be discussed with the patient in detail, and the final decision has to take into account both the surgeon’s judgment and the patient’s choice.

Acoustic Neurinomas in Patients in Poor Clinical Condition (Fig. 4.5)

If there is a reason for the patient’s poor clinical condition (e.g., internal medical problems) we manage that first and try to bring the patient into as good a condition as possible, so that all treatment options can be considered. The same approach is used in cases of concomitant hydrocephalus. In these cases, we prefer to carry out an endoscopic third ventriculostomy first, and if this is not possible, a shunting procedure is performed. If the patient’s condition remains stable but does not improve, we prefer to proceed with radiosurgery as the only treatment option. In the case of elderly patients with small tumors (grade I or II), the wait-and-see option is preferred, on the basis of the known natural history of these tumors.

Fig. 4.5 Most importantly, the question that has to be answered is: should the individual patient be treated or not? A no-treatment policy, i.e. a “wait-and-rescan” approach, is preferable in older patients (over 70) who are asymptomatic and have small lesions, if the lesion is in the only hearing ear, or when the patient is in poor clinical condition. We follow these patients with MRI scans every 6 months for the first year. If the lesion remains stable, scans are performed annually. If neurological complications or rapid tumor growth occur, we follow the algorithms shown in the figure.

Selection of the Patient’s Position on the Operating Table

In our department, the retromastoid (transmeatal) approach, with the patient in the sitting (or semisitting) position, is preferred. In our opinion, the advantage of the sitting position is that blood and cerebrospinal fluid drain away from the operative site, providing clear exposure. In most cases, the surgeon’s position is much more comfortable. open foramen ovale, our decision is to operate However, this is a controversial point in neurosurgery. Many surgeons feel more comfortable placing the patient in a modified park-bench position. When properly performed, this position can also provide surgeon comfort, along with excellent exposure and access to the cerebellopontine angle.

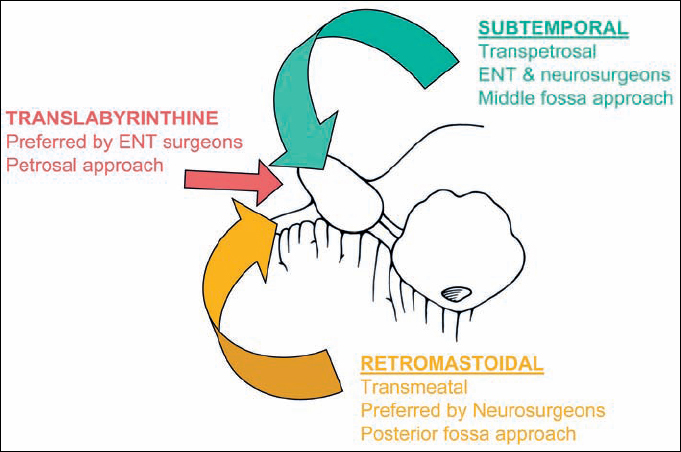

Selection of the Surgical Approach (Fig. 4.6)

The three main approaches for acoustic neurinomas are the retrosigmoid (transmeatal), the enlarged middle fossa, and the transpetrosal (translabyrinthine or retrolabyrinthine). Selection of the approach has always been a major topic of discussion between neurosurgeons and ear, nose, and throat (ENT) surgeons. As neurosurgeons, the present authors have been familiar over a long period of time with the retrosigmoid approach and the opportunities for individual modification it offers. As we can show from our clinical material, we have been able to remove all sizes of acoustic tumor with this technique—even the smallest ones located at the fundus of the internal auditory canal. It has to be accepted that in all cases of larger tumors (grades II, III, and IV), the retrosigmoid transmeatal approach is the best approach, for a number of reasons. In comparison with the translabyrinthine approach, the retrosigmoid approach provides a shorter operating time, a better approach angle for separation from the cerebellum and brain stem, and better exposure medial, superior, and inferior to the cerebellopontine angle for larger tumors. Only in cases of small tumors (grades I and IIa) in patients with good hearing is the middle fossa approach a viable alternative, in the hands of surgeons who are experienced with the technique and have acceptable results. The translabyrinthine approach might be an alternative if the surgeon is not familiar with the retrosigmoid transmeatal approach and a neurosurgeon is not available.

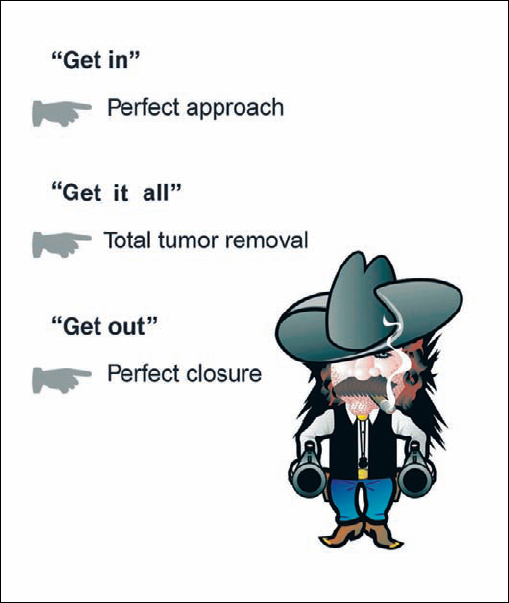

Total versus Subtotal Removal

As neurosurgeons, our preoperative intention in the majority of cases is to remove of the entire tumor. The philosophy we adopt resembles that of a bank robber—as suggested in Figure 4.7. Subtotal removal is the approach of choice preoperatively only in selected cases. We also consider that subtotal removal generally leads to recurrence, and the revision surgery that is subsequently required is more difficult and usually provides a poorer outcome in comparison with primary surgery. However, it must be realized that there are also exceptions to the philosophy of attempting complete removal in every case. For example, if the facial nerve is completely involved in the capsule of the tumor, an attempt at total tumor removal will cause permanent facial nerve palsy. To reduce the risk of facial nerve injury in such situations, we recommend leaving small parts of the capsule in place, where the tumor capsule is most adherent to the facial nerve. A similar situation is sometimes encountered in cases of grade II, III, or IV neurinomas that are adherent to the brain stem. It can happen that it is really not possible to separate all of the capsule without inflicting damage to the brain-stem surface. In such situations, we also recommend leaving a small portion of the capsule in place.

Fig. 4.6 The three possible routes to the inner meatus and the cerebellopontine angle.

Fig. 4.7 Over the years, we have followed a simple intraoperative strategy that has proved effective, which we call the “bank robber’s method”—meaning “get in, get it all, and get out.” “Getting in” means making the fastest and smallest opening possible in the individual case, using a defined step-by-step procedure. “Getting it all” means, whenever possible, total resection of the tumor. “Getting out” means carrying out the reconstruction and closure quickly and accurately in such a way that there is little outward trace that the patient has undergone an operation.

Special Situations

Tumors in patients with preoperative hydrocephalus. Obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) circulation by large acoustic tumors (grade IV) may produce hydrocephalus, with increased intracranial pressure. In these cases, we recommend either a shunting procedure or more and more an endoscopic third ventriculostomy.

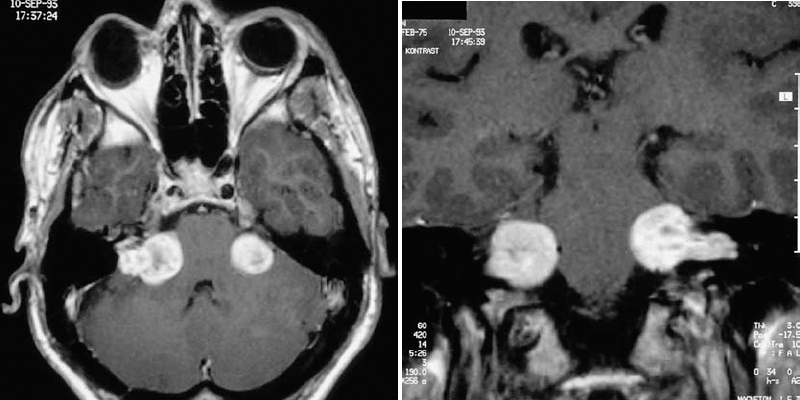

Patients with type 2 neurofibromatosis (Fig. 4.8, Table 4.1). The pathognomonic sign of type 2 neurofibromatosis is the presence of bilateral acoustic neurinomas. These cases are very difficult to manage, and the final treatment decisions depend on various factors, including the patient’s preoperative hearing level on each side, the size of the tumor, and other associated pathologies (e.g., other neurinomas, meningiomas, or gliomas). Operating on these tumors is generally much more difficult, due to the multilobular morphology seen in these cases, especially as the tumors become larger. The seventh and eighth cranial nerve fibers can become engulfed and infiltrated by tumor in cases of type 2 neurofibromatosis, in contrast to the typical situation in unilateral tumors, in which the nerves are simply displaced by the tumor.

Table 4.1 indicates our management approach in patients with bilateral acoustic neurinoma. The key factor is the patient’s preoperative hearing. When there is bilateral deafness, we recommend removing the larger tumor first, followed by the smaller one at a later time. If the results of radiosurgery in type 2 neurofibromatosis are satisfactory, it may offer an alternative for the smaller tumor. When there is unilateral deafness, the deaf side is treated. If microsurgery is not possible, or not accepted by the patient, we recommend radiosurgery. When there is preoperative hearing in both ears, we recommend treating the side on which hearing has declined first, no matter whether it is the side with the larger or smaller tumor. The goal in these patients is to maintain hearing as long as possible. As a general philosophy, it is in the patient’s best interests to have aggressive, proactive treatment of this disease. If removing a small tumor or stopping its growth with radiosurgery can save hearing, this will likely provide a longer period of time with preserved function than with the standard approach of observation until the patient shows significant symptoms. The conservative approach may often actually lead to the patient losing function at a much earlier stage than would otherwise have happened with a more aggressive treatment strategy. However, it is our experience that the final outcome in all of these patients is total deafness. The treatment strategy must also therefore include adaptive strategies (i.e., learning lip-reading and sign language) for the patient to facilitate communication once total deafness occurs. The initial results with auditory brain-stem implants, and in some cases cochlear implants, are very promising, and consideration will need to be given to these options in the coming years.

Fig. 4.8 a, b A typical case of type 2 neurofibromatosis in a young patient presenting with bilateral acoustic neurinomas.

Table 4.1 Management of bilateral acoustic neurinomas.

Bilateral deafness | Larger lesion operated on first, followed by the smaller one at a later date |

Unilateral deafness | Lesion on deaf side operated on first, whether it is the smaller one or not |

Bilateral hearing | Larger lesion operated on first; the smaller one on the side with better hearing is observed and operated on if hearing deteriorates |

Neuroanesthesiologic Considerations

Transesophageal Ultrasound (Sitting Position) (Figs. 4.9–4.13)

To detect air embolism at a very early stage, all patients placed in the sitting position are monitored using transesophageal echocardiography during the operation. The anesthesiologist is able to detect even the smallest air emboli long before clinical signs occur, such as a decrease in end-expiratory CO2. Since this was made a standard procedure, we have had no serious problems with air embolism in patients placed in the sitting position. We recommend simple internal jugular vein compression if the anesthesiologist detects air bubbles. The increase in venous pressure produced by jugular vein compression makes it easy to detect an open vein.

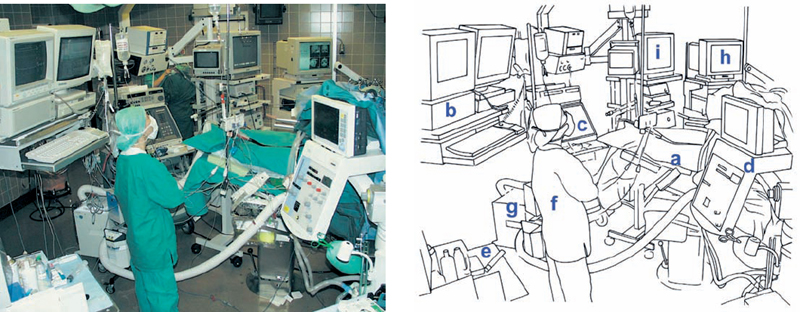

Fig. 4.9 The overall view of the neuromonitoring set-up in the operating room. The anesthesiologist’s workplace is beside the operating table (a). The monitors are mounted on the ceiling, with an automatic hydraulic arm (b). Ultrasound (c), the anesthesia apparatus and equipment for neuromonitoring (d), and the anesthesia trolley (e) are placed behind the anesthetist (f). Notice the so-called “bear hugger” (g), used to warm up the patient. On the other side of the operating table is the equipment for neuronavigation (h) and endoscopy (i).

Fig. 4.10 The ultrasound equipment for transesophageal echocardiography is an established part of the anesthesiology equipment during operations conducted with the patient in the sitting position.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree