Chapter 4 Middle east and arab american cultures

The nature and significance of the arab world

People who are Arabs extend from the Atlantic shores of Northwest Africa to the Persian (Arab) Gulf opening on the Indian Ocean, from the interior of Northern Africa to the whole Southern Mediterranean shore, and to the Southern border of Turkey. Furthermore, the Arab world embraces more than 5 million square miles, approximately one eleventh of the earth’s land mass. The Arab world in the Middle East includes more than 285 million people, which amounts to nearly one thirtieth of the population of humankind.

The Middle East is a vast area of the world stretching from the lands surrounding the eastern edge of the Mediterranean Sea to the areas of Southwest India. Although the U.S. Census Bureau (2001) identifies countries such as Iran and Iraq as Asian, this text considers them to be in the Middle East. The distinction was made on the basis of the cultural roots of the countries and the roots of the languages spoken, rather than any political issues.

Although Arab Americans are heterogeneous in origin and culture, they share in negative stereotypes and discrimination, related to the recent political events involving the Arab nations, such as the Gulf War of the early 1990s (Suleiman, 2001) and the subsequent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Although Arab Americans are less visible than other ethnic groups, the anti-Arab representation in the media makes them more visible in a negative way. There is considerable misunderstanding about the Middle Eastern people, particularly involving the beliefs and practices of non-Christian religions. Holidays such as Ramadan (associated with Muslims) and Passover (associated with Judaism), modes of dress, prohibitions about food products, fasting, and other practices often result in misunderstanding and stereotypes that can have an impact on clinical practices. (For a more detailed discussion of religious practices, see the Intervention section in Chapter 14.)

Most Arab immigrants in Brazil were Christians, the Muslims being a small minority in comparison. Intermarriage between Brazilians of Arab descent and other Brazilians, regardless of ethnic ancestry or religious affiliation, is very high; most Brazilians of Arab descent only have one parent of Arab origin. As a result of this, the new generations of Brazilians of Arab descent show marked language shift away from Arabic. Only a few speak any Arabic, and such knowledge is often limited to a few basic words. Instead, the majority, especially those of younger generations, speak Portuguese as a first language. In Brazil, there are 7 million people of Lebanese origin, 3 million of Syrian origin, and 2 million from various other Arab origins, most notably Palestinians, Iraqis, Egyptians, and Moroccans. Canadians of Arab origin make up one of the largest non-European ethnic group in Canada. In 2001, almost 350,000 people of Arab origin lived in Canada, representing 1.2% of the total Canadian population. Of the Arab Canadians, 14% have their origins in Lebanon, 12% in Egypt, 6% in Morocco, 6% in Iraq, 4% in Algeria, and 4% in Palestine.

Geographic diversity

Today’s Arab world includes diverse countries from the Mediterranean area and northern Africa to southwestern Asia. The countries include the large cosmopolitan areas such as Cairo in Egypt, Jerusalem in Israel, Jeddah in Saudi Arabia, and Beirut in Lebanon. They also include the rich agricultural area of the Fertile Crescent as well as the vast rural areas of the deserts in which most Arabs continue to live. Countries of the Middle East include Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Algeria, Morocco, Turkey, and Tunisia. Other Arab nations include Kuwait, Mauritania, Oman, Palestine, Israel, Qatar, Somalia, Sudan, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen (Hsourani, 1991; Shipler, 1987).

The Middle East contains four main geographic regions that cut across national and political divisions. These are the northern tier, the Fertile Crescent, the largely desert south, and the western area. The northern tier, which encompasses Turkey, northern Iraq, and semiarid plateaus, depends on irrigation and light rainfall to support agriculture. The major language groups in the northern tier include Arabic, Kurdish, Turkish, and Farsi (Isenberg, 1976). The primarily desert southern lands include the oil-rich United Arab Emirates, Oman, and the two Yemeni Republics (North and South). The Fertile Crescent consists of the Gulf States of Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan. The Fertile Crescent forms the southern border of the northern tier. It stretches northward through Israel and Lebanon and then arches across northern Syria to the valleys of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers in Iraq. The primary languages spoken in the Fertile Crescent and the southern sectors of the Middle East are Arabic, Hebrew, and dialects of Aramaic, Berber, and Nubian origin (Isenberg, 1976). Djibouti, Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt capsule the western areas of the Middle East. The languages of this vast area include French, Arabic, and Aramaic.

The Middle East is a predominately Arabic-speaking region that is populated primarily by Arabs. This notion requires clarification, however, because the term Arab itself is not strictly definable. In a purely semantic sense, no people can be classified as Arab because the word connotes a mixed population with widely varying ethnographic and racial origins. Some people of Negro, Berber, and Semitic origins identify themselves as Arab (Wilson, 1996). Hence, Arab is best used within a cultural context (Lamb, 1987). Arab countries are those in which the primary language is Arabic and the primary religion is Islam. Consequently, the Middle East makes up the greatest portion of the Arab world, a world that reflects one of Islam from an embryonic phenomenon into a vast sphere of influence and civilization.

According to Lamb (1987) and Mansfield (1992), approximately 200 million Arabs occupy the Arab world. The paradox of parallel modernization and political turmoil has influenced language, learning, and SLP-A services in the Middle East. The hugely increased revenue flowing into the oil-producing Arab countries has facilitated the early phases of the development of SLP-A services, whereas the turmoil of civil and regional wars has created populations of patients of all ages who need services to treat communication disorders.

Additionally, age-old traditions of consanguinity (blood relationships) contribute to a variety of communication problems among Arab speakers. Jaber and colleagues (1997) studied the frequency of speech disorders in Israeli Arab children and its association with parental consanguinity. Twenty-five percent of 1282 parents responding to a questionnaire indicated that their children had a speech and language disorder. After examination by a speech-language pathologist (SLP), rates of affected children of consanguineous and nonconsanguineous marriages were 31.0% and 22.4%, respectively (P < .01).

Arab americans and arab origins

The second major wave of Arab immigration began in the 1940s after World War II. They were primarily well-educated professional Muslims who, like their predecessors, sought the educational and financial opportunities in the United States. The new wave sparked a resurgence of ethnic pride among descendants of the early immigrants. Since the mid-1960s, the number of Arabs living outside the Arab world has increased significantly. The United States, Germany, Brazil, Israel, England, France, Canada, and Sweden have among the largest populations of Arabs living outside the Middle East.

Current estimates of the number of Arab Americans living in the United States are about 3 to 5 million. Estimates vary because the U.S. Census Bureau does not use Arab American as a classification. In addition, recent immigrants from some Arab or Middle Eastern countries are reluctant to give personal and confidential information to the government because of the sociopolitical issues of the past decade. Officially, as shown in Table 4-1, according to extrapolated U.S. Census data, there are an estimated 1.5 million Arab Americans living in the United States. There are approximately 200,000 persons from Lebanon, 179,000 persons of Egyptian ancestry, and 149,000 Americans of Syrian ancestry.

TABLE 4-1 Population by Selected Arab Ancestry Group in the United States, 2008

| Population | No. |

|---|---|

| Total Arab | 1,549,725 |

| Egyptian | 179,592 |

| Iraqi | 69,277 |

| Jordanian | 59,233 |

| Lebanese | 501,907 |

| Moroccan | 77,468 |

| Palestinian | 85,745 |

| Syrian | 149,541 |

| Saudi Arabian | 260,427 |

| Other Arab | 189,300 |

From U.S. Census Bureau (2008). American Community Survey, B04006: People reporting ancestry. Retrieved March 2010 from http://www .census.gov/acs/www/.

Persons of Arab descent in the United States today are as diverse as the many countries of the origin of their descendants. They represent a variety of religions, values, and degrees of acculturation and assimilation. Because the major waves of immigration of persons from the Middle East occurred in the first half of the 19th century, 82% of Arab Americans are U.S. citizens, and 63% were born in the United States. As a cultural group, they are well educated, with 62% having at least some college education (compared with 45% of the non-Arab U.S. population) and twice as many as in the non-Arab U.S. population having a master’s degree or higher. More than 60% of Arab Americans hold white-collar or professional occupations, 12% are self-employed, and 20% are in retail trade business. Most reside in the urban areas of Detroit, New York City, Washington DC, Los Angeles, Chicago, Boston, Cleveland, and New Jersey (Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1998).

Arab american families and arab lifestyles

Family life, religion, and harmony are important to nearly all Arab and Middle Eastern families. The family is the centerpiece of society in Arab states. All other establishments evolve from this basic unit. Most Arab American families are large. It is not uncommon for several generations to live together as an extended family, with the oldest man being the head of each family; the families are patriarchal, being based around the father, his sons, their wives, and their children. Although separated from their natal family, ties between women and their blood relatives are continued. Women frequently consult their natal families if there are problems with the children or other problems. Clinicians need to respect the sanctity of the nuclear and extended family and the role of elders within the family (Schwartz, 1999). Inviting the family to participate in assessment and intervention can be useful in helping the family understand the needs of the individual. In most Muslim families, the women are responsible for instilling the proper cultural values in children through child-rearing practices.

The concept of honor is very important in the lives of Arabs and Middle Eastern society. Fear of scandal is a major consideration in their daily lives. Upholding the honor of the family is vital. Because Arabs are very sensitive to public criticism, clinicians should express concerns to Arab American families in a way that prevents the “loss of face” (Adeed & Smith, 1997; Jackson, 1995, 1997).

Women in middle eastern culture

In this age of globalization, Arab women are entangled in the simultaneous movements of contraction and expansion whereby people of all cultures grapple with the global economy and debate universal values. The restrictions that many Arab women face are often like mirrors of the primordial ties of Arab ethnicity, language, and religions. Consequently, Arab women are subjected to conditions and challenges in the Arab world that vary in intensity from one Arab country to another. Such conditions and challenges include populations in which as many as one in three is younger than 14 years of age; inadequate or underdeveloped education systems (especially educational entities for females); economies struggling to create and maintain competitive 21st century employment structures; limited water resources; limited or nonexistent political rights; societies grappling to define the role of women; and the crisis of identity (the most fundamental measure of who and what a person or society is).

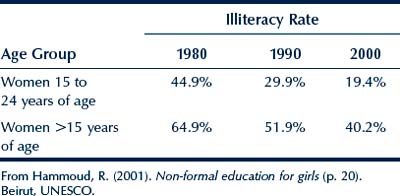

The Arab region has some of the world’s lowest adult literacy rates, with only 62.2% of the region’s population 15 years and older able to read and write in 2000 to 2004, well below the world average of 84% and the developing countries’ average of 76.4%. Great variations exist among the Arab states in their literacy rates for the group aged 15 years and older. The most recent data reveal that literacy rates range from 80% and higher in nine countries (Jordan, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Kuwait, Lebanon, Qatar, and Libya), which are relatively small states with the exception of Saudi Arabia, to less than 75% in nine other countries with large populations, with Iraq, Mauritania, and Yemen standing as low as 40%, 41.2%, and 49%, respectively. There is considerable disparity between the education of girls and that of boys in the Arab world and also across countries. In some countries, nearly 20% of girls between the ages of 6 and 11 years do not attend school (Hammond, 2006). Female literacy rates of those aged 15 years and older in the Arab world today range from 24% in Iraq to 85.9% in Jordan. Although improvements have been made in education of women in recent years, high rates of illiteracy among women persist in most of the Arab countries; indeed, women today account for two thirds of the region’s illiterate population, and according to the Arab Human Development Report of 2002 (p. 52), this rate is not expected to disappear until 2040 (Daniel, 2005, p. 6) (Table 4-2).

Religion in arab life

Religion is very important to Arab and Arab American families. Although most are Muslim, many follow the Christian beliefs of their ancestors from the early wave of immigration. Some Muslim Arab American families send their children to private Muslim schools so that they can receive education consistent with the religious beliefs of the family (Zehr, 1999). Some families opt to send their children to public schools. As the number of Arab American children in the public schools increases, many schools have adapted their programs and practices to accommodate the religious needs of the children. This includes adapting school menus to have alternatives to pork, which is not consumed by Muslims; allowing a place for prayer at the noon hour; and adapting the school lunch programs to allow for the fasting, required during Ramadan. Many school programs are reducing the emphasis on celebration of Christian holidays to relieve Muslim students from the stresses of participating in Christian and Judaic religious practices. Clinical materials and tests are being modified to remove items that may be specific to a particular Christian religion, such as items related to the celebration of Christmas. Clinicians should be sensitive to the religious beliefs of clients in selecting items for assessment and intervention.

Most persons in the Middle East are farmers or laborers, although a great deal of the land space in the Middle East is unfit for agricultural use (Hitti, 1985). Because the oil wealth of the Middle East has benefited only a fraction of the Arab population, many inhabitants of the Arab world have speech, language, and hearing problems owing to lack of medical, educational, and human resources services. These inhabitants are often born into communities that do not systematically provide these services. According to Isenberg (1976), the reality of limited natural resources in most of the Middle East explains why the Arab world must be considered among the underdeveloped sectors of the world. Limited resources, too few trained professionals, and lack of access to services negatively influence speech, language, and hearing integrity among large populations of Arab speakers. For persons seeking assistance from SLPs trained in the Middle East in the major cities such as Cairo, Jeddah, and Amman, the supply of clinicians is considerably below the demand for services. When the civil and regional political turmoil is considered, access to available services in the Middle East becomes even more restricted.

Arabic language

Ethnic diversity among arab american speakers

The Arab world, owing to its ancient and current history, remains a diverse melting pot of humanity, largely a result of Islamic pilgrimages. Because national languages and SLP-A dynamics are influenced by histories of invasions, conquests, slavery, and most importantly, the onset of Islam, the inhabitants of the Arab world represent a multiplicity of subgroups, all struggling to coexist in a collision of cultures. Perhaps the most useful method for classifying persons from the Middle East is according to the language they speak, religions they embrace, and traditions they honor (Mansfield, 1992). This categorization allows for four major national groups: the Turks, Iranians, Israelis, and Arabs. The extremely close relationships and overlapping of linguistic, cultural, racial, and sociologic factors of all these groups foster many of the chronic problems of Middle Eastern society.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree