CHAPTER 35 Middle Fossa Meningiomas

INTRODUCTION

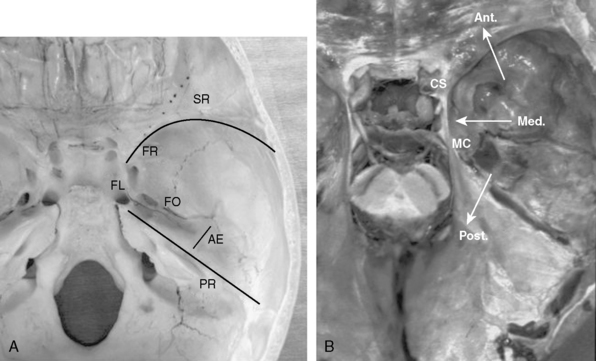

The middle fossa is a common localization for intracranial meningiomas. The floor of the middle cranial fossa is formed by the greater wing of the sphenoid bone joining the squamosal part of the temporal bone.1 Medially, it articulates with the clival portion of the occipital bone at the petroclival fissure. The foramen lacerum is located at the junction of the temporal, sphenoid, and occipital bones. The floor of the middle cranial fossa is bound anteriorly by the greater wing of the sphenoid (sphenoid ridge), posteriorly by the superior petrosal sinus (petrous ridge), and medially by the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus and Meckel’s cave (Fig. 35-1A, B). The bone and the dura mater of the middle fossa floor are supplied by branches of the middle meningeal artery and by caroticocavernous branches.

Meningiomas can involve the middle fossa primarily or secondarily. Pure middle fossa meningiomas originate anterolaterally and posterolaterally at the floor of the middle cranial fossa and extend to the vicinity of the superior petrosal sinus and the exit of the vein of Labbé.2 However, the majority of meningiomas encountered at the middle fossa are secondary extensions and involve the sphenoid wing, superior orbital fissure, cavernous sinus, Meckel’s cave, petroclival area, and the cerebellopontine angle. Some extend extradurally to the pterygopalatine fossa and infratemporal fossa through the foramen rotundum and ovale. Other authors reported unusual cases of the middle fossa meningiomas arising from the geniculate ganglion,3 the middle ear,4 and other parts of the temporal bone.5 Meningiomas of the middle fossa can also occasionally invade along the temporal base in en plaque fashion. Therefore, knowledge of microsurgical anatomy and variations of lateral skull-base approaches are essential for planning a surgical treatment in patients with middle fossa meningiomas.

SURGICAL APPROACHES FOR MIDDLE FOSSA MENINGIOMAS

For resection of most pure middle fossa meningiomas, a subtemporal and/or middle fossa approach or suprapetrosal approaches are adequate.6 In contrast, for meningiomas of the middle fossa that extend into surrounding skull-base structures (Fig. 35-1B), appropriate skull-base approaches should be tailored based on the preoperative imaging studies. Zygomatic osteotomies facilitate these approaches by widening the surgical corridor in exposure of the middle fossa, and enable access to the infratemporal fossa. In case of anterior extension to the frontal fossa, sphenoid wing, and superior orbital fissure (SOF), orbitozygomatic approaches may be planned.7,8 In case of posterior extension to the cerebellopontine angle, anterior and/or posterior petrosal approaches may be appropriate.9,10 In case of inferior extension to the infratemporal fossa, the zygomatic infratemporal approach may be chosen.11 Depending on the tumor location and extent, combinations of these approaches may be used to achieve safe and total removal of widely invasive tumors.

Epidural or Subdural Subtemporal Approach (Middle Fossa Approach)

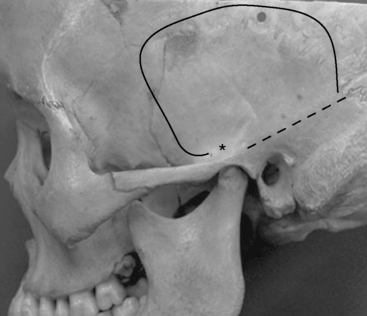

Most meningiomas of the middle fossa can be resected with the subtemporal approach. The lowest point of the middle cranial fossa is roughly at the level with the upper border of the zygomatic arch and is slightly posterior to the articular tubercle of the temporomandibular joint.12 Zygomatic osteotomies therefore facilitate the exposure of the anterior part of the middle cranial fossa. The surgical landmark of the base of the middle cranial fossa is the line between just above the root of the zygoma and the supramastoid crest (Fig. 35-2).

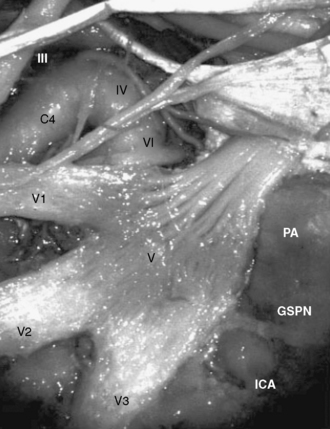

The petrous portion of the internal carotid artery (ICA) courses posterolaterally toward Meckel’s cave, and the transition between petrous and cavernous portion of ICA occurs below the trigeminal ganglion (Fig. 35-3). The Glasscock triangle is limited by the posterior rim of the foramen ovale, foramen spinosum, and the posterior border of V3. The GSPN usually runs just above this triangle, which is an important landmark of the lateral border for preserving the petrous ICA while drilling the petrous apex.9 When the GSPN is adherent to the dura of the middle fossa, it can be dissected together with the middle fossa dura.

During epidural dissection of the divisions of the trigeminal nerve, it is quite important to respect the microsurgical anatomy of the cavernous sinus and Meckel’s cave. The dura of the middle fossa has two layers: the outer periosteal layer and the inner meningeal layer. At its exit from the dura, the meningeal layer of the dura envelopes the epineurium of the nerve and after its entry into the bony foramens of the middle fossa the nerve is covered by the periosteal layer. Therefore, by cutting the periosteal layer of the dura and dissecting between the meningeal layer of the dura and the epineurium in the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus and Meckel’s cave, the divisions of the trigeminal nerve can be exposed extradurally. Peeling off the meningeal layer of the V3 and Meckel’s cave will also facilitate the exposure of the petrous apex for the anterior petrosal approach.9 This technique will also provide a wide exposure from the SOF to the foramen ovale and Meckel’s cave. The disadvantage of the subtemporal approach is the need for significant temporal lobe retraction and resultant posterior venous congestion. Removal of the zygoma and lumbar cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage may minimize the need for temporal lobe retraction. The epidural subtemporal approach provides limited exposure of the tumor, because V2 and V3 may limit the exposure. In addition, traction injury of GSPN and of the geniculate ganglion may result in facial nerve palsy. Preservation of the arachnoid planes and the surrounding neurovascular structures should be attempted. However, some meningiomas may invade the arachnoid and even the pial sheets. In these cases, the operating surgeon will decide how aggressive the surgery will be, depending on the structures involved and the patient’s clinical situation.13

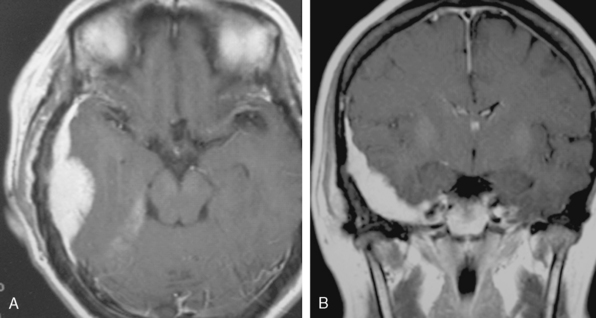

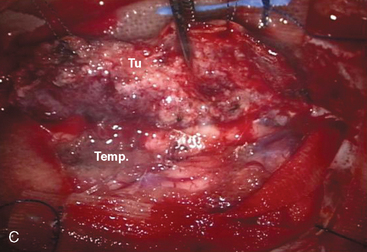

A 47-year-old woman presented with left temporal pain, which was present for the last few years. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an en plaque meningioma along the right middle fossa, extending to the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus and Meckel’s cave (Fig. 35-4). A right cerebral angiogram revealed the tumor blush on the venous phase and indicated that the tumor was mainly fed by the middle meningeal artery. Computed tomography (CT) showed hyperostosis of the temporal bone. Gross total removal was achieved with a right zygomatic subtemporal approach. Wide exposure of the floor of the middle fossa made it possible to safely resect the hyperostotic bone as far as medially as the lateral aspect of the foramen ovale and foramen rotundum. The middle fossa dura was also widely resected after peeling off the outer layer of the lateral wall of the posterior cavernous sinus. Cavernous sinus involvement may represent a limit to achieving total resection. Skull-base reconstruction is performed using a vascularized temporal fascial and muscle flap. In case of a large bone defect, artificial materials such as bone cement or ceramic material can be used for cranioplasty. Close observation under imaging studies is essential because of the high frequency of recurrence in patients with en plaque meningioma.14

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree