CHAPTER 31 Minimally Invasive Approach to Frontal Fossa and Suprasellar Meningiomas

INTRODUCTION

During the last two decades, as a result of advances in low-profile instrumentation, surgical navigation, and endoscopy, keyhole surgical routes have been increasingly used to approach a wide spectrum of brain and skull-base tumors. For frontal fossa and suprasellar meningiomas, the extended transsphenoidal and the supraorbital “eyebrow” craniotomies are now often used for their removal.1–20 Although these two approaches traverse entirely different anatomic territories to reach the same intracranial target and have markedly different closure requirements, they are similar in their technically demanding nature, requiring an ability to maneuver through a narrow operative corridor. The transsphenoidal approach, which obviates brain retraction, minimizes optic apparatus manipulation, and allows early identification of the pituitary gland and infundibulum, has been shown to be effective for smaller midline meningiomas.1,2,6,7,9,16 It is increasingly performed via an endonasal approach with microscopic and endoscopic assistance1,2,7,9,13,14,16 or by a purely endoscopic approach.6,15 The two major drawbacks of the endonasal approach are (1) limited access to lesions lateral to the supraclinoid carotid arteries and optic nerves and (2) challenges in achieving an effective skull-base closure. Supraorbital keyhole craniotomy is also performed with minimal or no brain retraction and allows excellent access to a broader region within the frontal fossa and suprasellar area.3,4,8,11,12,17–20 The minimal scalp tissue and muscle dissection required promote a less painful recovery compared to standard craniotomies.3,17–20 The major drawback of this approach is the potential for limited maneuverability given the small craniotomy, which typically measures 15 to 20 mm by 25 to 30 mm. Herein we describe the use of the endonasal and supraorbital keyhole approaches for removing frontal fossa and suprasellar meningiomas, including a discussion of selection criteria for their use, their respective limitations, potential pitfalls, success rates, and complications.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND INCIDENCE

Meningiomas of the anterior cranial fossa arise in various locations and comprise approximately 12% to 22% of all intracranial meningiomas.21–23 They are commonly divided into two major subgroups: olfactory groove meningiomas that arise over the cribriform plate and frontosphenoid suture and suprasellar meningiomas, the most common of which are midline tuberculum sellae meningiomas. Other suprasellar meningiomas may arise from the diaphragma sellae itself or from the arachnoidal attachments along the anterior and posterior clinoids. Some frontal fossa meningiomas span both the olfactory groove and tuberculum sellae territories and are not easily classified.23,24 Most olfactory groove meningiomas become rather large before producing symptoms (often >3 cm in size) such as headache, personality changes, anosmia, or seizures. Large olfactory groove meningiomas that extend posteriorly to the posterior planum may encroach upon the optic apparatus producing visual loss.24–26 In contrast, most tuberculum sellae and other suprasellar meningiomas are diagnosed at a smaller size as a result of visual loss from chiasmal or optic nerve compression.27–30 With progressive growth, tuberculum sellae meningiomas develop lateral and superior extensions, often resulting in vascular encasement, cavernous sinus invasion, and optic canal invasion. Larger tumors typically, greater than 3 or 4 cm in diameter, often encase the anterior cerebral artery complex.

HISTORY AND EVOLUTION OF MICROSURGERY FOR FRONTAL FOSSA AND SUPRASELLAR MENINGIOMAS

Traditional Approaches

Many macrosurgical and microsurgical series for removal of olfactory groove and suprasellar meningiomas have been published since the first reports of removal of an olfactory groove meningioma by Durante in 1884 and of a suprasellar meningioma by Cushing and Eisenhardt in 1938.31,32 In most series over the last two decades, olfactory groove and suprasellar meningiomas have been approached through several routes including bifrontal, unilateral frontal, pterional, and fronto-pterional.22–30,33–40 In microsurgical series of olfactory groove meningiomas, high rates of total tumor removal ranging from 85% to 100% are reported with both pterional and bifrontal routes with relatively low morbidity.24–26 The recurrence rate ranges from 5% to 41% over 10 years and appears to be predominantly related to subtotal removal (Simpson grade 2 or higher) in the floor of the anterior cranial fossa, and the underlying ethmoid or sphenoid sinus area.25,26,33,37,41,42

Achieving complete removal of suprasellar meningiomas is often more problematic because of tumor extensions along the optic apparatus, hypothalamic–pituitary axis, anterior circle of Willis, and cavernous sinus. In recent series, total resection of suprasellar meningiomas has ranged from 67% to 100% with rates of visual decline ranging from 0 to 20% and mortality ranging from 0 to 8.7%, respectively.22,23,27–30,34–36,38,39 Even with technically demanding approaches such as extradural clinoidectomy for optic nerve decompression, visual worsening of up to 10% has been reported.30,38

Minimally Invasive “Keyhole” Approaches

As Wilson stated more than 35 years ago “the ideal exposure is one that is large enough to do the job well, while preserving the integrity of as much normal tissue as possible.”43 With the development of frameless surgical navigation, endoscopy, as well as lower profile microsurgical instruments and aspirators, this “keyhole” concept has been increasingly used for removing a wide spectrum of intracranial lesions, including meningiomas.44 This concept is based on the observation that with a small craniotomy, the available exposure expands as the distance from the bony opening increases, so that with an optimally placed craniotomy, exposure is more than adequate (Fig. 31-1). These advances in keyhole surgery have resulted in a shift away from traditional larger anterior and anterolateral skull-base approaches such as the pterional, bifrontal, and orbitozygomatic craniotomies and the midface degloving transsphenoidal approach. Likewise, there is waning enthusiasm for the transpetrosal approach for petroclival tumors and a resurgence of the retrosigmoid craniotomy and endonasal transclival approach to reach such tumors.36,37,45,46

Supraorbital approach

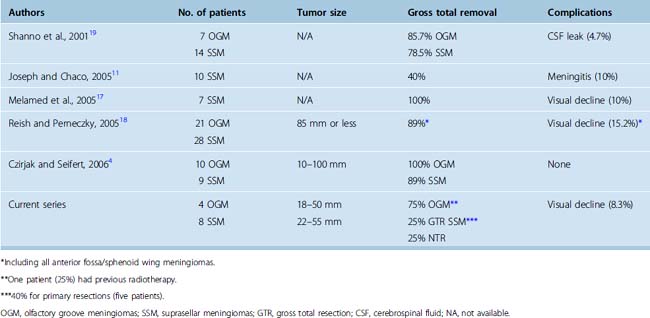

The supraorbital approach has evolved from more traditional frontal and frontotemporal approaches.47–50 The small craniotomy with an incision directly through the eyebrow obviates problems with mastication and temporalis wasting because of limited temporal muscle dissection and retraction. More importantly, placement of the craniotomy immediately above the orbital roof and along the floor of the frontal fossa affords access with minimal brain exposure and brain retraction.3,18 As recently demonstrated in an anatomic study by Figueiredo and colleagues using a slightly larger (30 mm) supraorbital craniotomy than is typically possible through an eyebrow incision, the area of exposure was similar between the supraorbital and traditional craniotomies, although it affords narrower angles of exposure.51 However, even with the narrower angles of horizontal and vertical exposure using the supraorbital craniotomy, many lesions of the frontal fossa and parasellar area are readily accessible as shown by Perneczky and others.3,4,18,44 Similar rates of total or near total resection of anterior cranial fossa meningiomas using the supraorbital approach have been reported when compared to traditional transcranial approaches (Table 31-1), ranging from 86% to 100% by the supraorbital route for olfactory groove meningiomas,4,18,19 and from 40% to 100% for suprasellar meningiomas.4,11,17–19 In these series, incomplete resection was typically attributed more to tumor invasiveness as opposed to inadequate exposure.4,11,17–19

Extended endonasal transsphenoidal approach

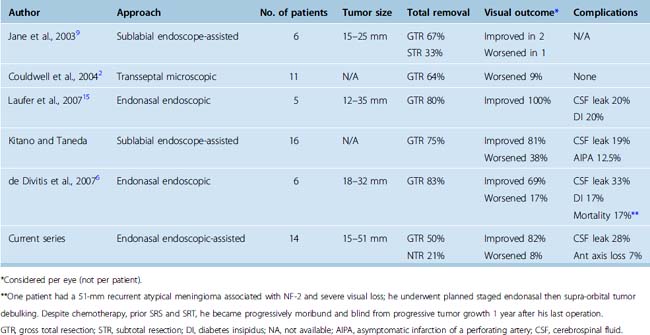

The transnasal approach is also considered a keyhole approach with the exposure expanding from the piriform aperture for the sublabial transsphenoidal approach or from the nostril for the endonasal approach. The obvious advantage of these approaches for midline frontal fossa and parasellar meningiomas is that the nasal cavity and ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses provide a direct route to the tumor without the need for brain retraction. In 1987, Weiss described the microscopic extended approach for the treatment of supradiaphragmatic craniopharyngiomas.52 Subsequent modifications of this approach have been described by multiple groups including the endonasal endoscope-assisted method and the fully endoscopic endonasal method for removal of suprasellar and olfactory groove meningiomas.1,2,5–7,9,10,14–16,53,54 In several recent reports, the extended transsphenoidal approach for tuberculum sellae meningiomas has yielded total or near total removal rates of 57% to 85% with tumor sizes ranging from 12 to 37 mm (Table 31-2).2,6,9,14–16 Transsphenoidal removal of tuberculum sellae meningiomas appears to result in similar visual recovery rates and visual worsening rates compared to transcranial approaches, although in one recent report by Kitano and colleagues, visual recovery was better by the transsphenoidal route.6,14,15 Visual improvement has ranged from 33% to 100%, with most reports noting greater than 50% visual improvement while visual decline has ranged from 0 to 38%, although visual worsening is less than 20% in most reports.2,6,7,15 The most common complication associated with the transsphenoidal or endonasal removal of suprasellar meningiomas has been inadequate skull-base repair and postoperative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks. In recent series of endonasal endoscopic and transsphenoidal microscopic approaches, the rates of postoperative CSF leak have ranged from 0 to 33%, although they have been decreasing in recent years.2,6,9,14–16

Regarding endonasal removal of olfactory groove meningiomas, there is relatively limited outcome data to date. However, this is becoming a more frequently utilized route for removal of these tumors at specialized centers with considerable endoscopic expertise.10,53,54 As with endonasal removal of suprasellar meningiomas, the most common complication using this approach is postoperative CSF leak.

PATIENT SELECTION FOR KEYHOLE MENINGIOMA REMOVAL

Suprasellar Meningiomas

For tuberculum sellae and other suprasellar meningiomas, tumor size and lateral extension are the two key factors that should determine whether a transsphenoidal, supraorbital, or conventional transcranial approach is used. As our results and others suggest, most midline tuberculum sellae meningiomas less than 30 to 35 mm in diameter can be removed by either the endonasal or supraorbital routes even in the setting of a normal sized sella.1,2,5–7,9,14,15 Both approaches allow excellent access for effective optic apparatus decompression with a high rate of visual recovery. However, the endonasal approach does not allow safe access to tumor lateral to the supraclinoid carotid arteries and the optic nerves and along much of the optic canal except medially. In contrast, the supraorbital approach allows access and excellent visualization to both of these areas. Therefore, larger meningiomas greater than 30 to 35 mm in diameter, those that extend well lateral to the supraclinoid carotid arteries or those that cause vascular encasement (see Fig. 31-1) are more safely approached by a supraorbital route or traditional transcranial approach. Regarding pituitary hormonal function, given that the pituitary stalk is pushed posteriorly by tuberculum sellae meningiomas, both the endonasal and supraorbital approaches are associated with a low rate of new endocrinopathy and a high likelihood of preserving the infundibulum. Concerning skull-base closure, a supraorbital craniotomy is relatively simple to close even if the frontal air sinus is transgressed, which occurs in fewer than 10% of cases. In contrast, endonasal avin removal of a tuberculum sellae meningioma will always result in a large skull-base defect and grade 3 CSF leak.55 Although postoperative CSF leak rates for extended suprasellar and transplanum transsphenoidal approaches have been improving considerably during the last 5 years for both microscopic and endoscopic procedures, skull-base repair remains a major issue to consider carefully before embarking on endonasal meningioma removal.55–59

Olfactory Groove Meningiomas

The ideal olfactory groove meningioma to remove by a supraorbital route is one that is less than 50 to 60 mm in maximal diameter and that does not extend to the most anterior extent of the frontal fossa, particularly on the side contralateral to the approach. Provided the tumor growth is within the arc of exposure of the supraorbital route, even meningiomas up to 100 mm in maximal diameter have been removed by this route.4 However, the anterior frontal fossa recess, particularly the contralateral anterior cribriform plate area, is a relative “blind spot” for the supraorbital approach.17,51 In addition, extensive tumor invasion of the ethmoid or sphenoid sinuses may be considered a contraindication for supraorbital removal because the small craniotomy limits the ability to achieve an adequate frontal fossa floor repair should tumor removal extend into the ethmoid or sphenoid sinuses. Tumors that exhibit far anterior bilateral extension or which have extensive growth into the paranasal sinuses are probably best approached from a traditional bifrontal, pterional, or other skull-base craniotomy.24,26,40

For endonasal removal of olfactory groove meningiomas, the most important consideration is tumor size, lateral extension, and whether there is vascular encasement of the anterior cerebral complex by the tumor. The small corridor between the two orbits (22 ± 4 mm)10 afforded by the extended endonasal approach allows complete resection only for tumors medial to the mid orbit as described by Kassam.(Kassam, personal communication). In addition, if there is vascular encasement of the anterior cerebral vessels by tumor, a transcranial removal is recommended. Finally, as with the extended transsphenoidal approach for tuberculum sellae meningiomas, the challenge of achieving an effective skull-base repair and avoiding a postoperative CSF leak remains a major consideration. Given these issues, endonasal removal of olfactory groove meningiomas should be attempted only by experienced endoscopic teams.10,53,54

INSTRUMENTATION

Given the restricted visualization and reduced angles of exposure of any keyhole approach with an operating microscope, endoscopic visualization should be utilized in all cases, at least intermittently to provide a more panoramic view and to assist with tumor removal in the far recesses of the exposure. Endoscopes for keyhole surgery should include 4-mm rigid endoscopes (18 cm in length) with 0-, 30-, and 45-degree angled lenses (Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany)60–64

Use of a micro-Doppler probe for vessel localization localizing is also recommended for all keyhole approaches. For example, in the supraorbital approach, after initial tumor debulking of an olfactory groove or tuberculum sellae meningiomas, localizing the anterior cerebral artery complex behind a rind of tumor with the Doppler can be very helpful. Similarly, as we have shown previously, localizing the cavernous carotid arteries before dural opening in the endonasal approach is also highly recommended and appears to reduce the risk of a cavernous carotid injury.65

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree