Money Matters: Funding Care

Martin Knapp

David P.A. McDaid

Sujith Dhanasiri

Introduction

The primary concerns of anyone working with children and adolescents with mental health problems are alleviation of symptoms, promotion of quality of life, support of families, and improvement of broad life chances. These should also be the primary concerns of those with responsibility for resource allocation, whether it is deciding how much funding can be made available, how it is shared between competing uses, or how to improve efficiency in its use. These latter can be seen as economic questions, but they cannot be answered without a clear understanding of child and family needs and the outcomes of interventions.

Interventions for children and adolescents include primary prevention of behavioral and emotional problems, services that respond to the emergence of such problems, treatments that directly address symptoms and their immediate consequences, and actions targeted on longer term, broader implications for individuals and communities. For almost any such intervention to be successful—indeed, for it to be initiated—skilled staff are needed, supported by appropriate physical and other resources. In turn, because little in life is free, this requires commitment of the necessary finances.

The purpose of this chapter is to explore these links between finances, resources, and achievements. We first introduce a conceptual framework that summarizes the main connections linking resources to individual and family outcomes. One source

of complexity that runs throughout the arguments in this chapter is that many children and adolescents have multiple needs, often prompting multiple responses—from health care, education, social work, criminal justice, and other services. Each of these service sectors has its own funding streams and associated arrangements for allocating resources; we consider this mixed economy in the third section. We then turn to a discussion of financing arrangements: How are child and adolescent mental health services funded? In judging whether financing arrangements are delivering the services and outcomes needed and wanted, we refer to two widely discussed performance criteria: efficiency (the balance between outcomes and what it costs to achieve them) and equity (whether outcomes, access, and burdens are fairly distributed). Achieving better performance by those criteria is often hampered: We therefore next discuss the resource barriers in the way of progress. The concluding section summarizes the key messages.

of complexity that runs throughout the arguments in this chapter is that many children and adolescents have multiple needs, often prompting multiple responses—from health care, education, social work, criminal justice, and other services. Each of these service sectors has its own funding streams and associated arrangements for allocating resources; we consider this mixed economy in the third section. We then turn to a discussion of financing arrangements: How are child and adolescent mental health services funded? In judging whether financing arrangements are delivering the services and outcomes needed and wanted, we refer to two widely discussed performance criteria: efficiency (the balance between outcomes and what it costs to achieve them) and equity (whether outcomes, access, and burdens are fairly distributed). Achieving better performance by those criteria is often hampered: We therefore next discuss the resource barriers in the way of progress. The concluding section summarizes the key messages.

The Production of Welfare

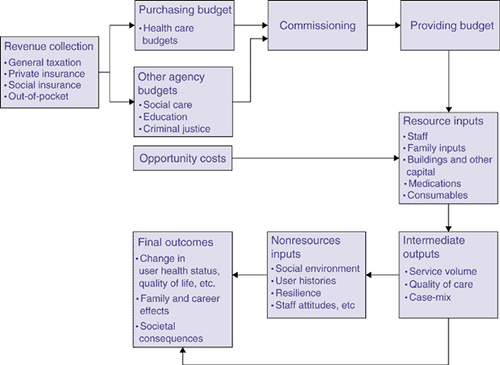

As a starting point, it is helpful to explicate the links between budgets, staff, and other resources hired or purchased, treatments and other services thereby delivered, and health and quality of life improvements hopefully experienced by individuals, families, and communities. A simple representation of a treatment and care systems helps to identify the probable connections between key entities (Figure 1.6.1): Revenue collection is the process by which health, education, social services, and other systems receive money from individuals, households, employers, and other organizations.

The funds thereby available to those systems are the purchasing budgets, to be allocated between competing needs and demands.

Commissioning is the process by which purchasers (e.g., insurance funds and government departments) transfer funds to service providers in return for (usually) contractually agreed-upon services.

Providing budgets are the funds available to the bodies that actually deliver services.

For those services to be delivered (whether health promotion, assessment, treatment, or supervision), resource inputs are employed: staff, buildings, equipment, medications, and other consumables.

Some resources are not bought and sold in markets, such as family care, volunteer inputs, and support from faith and community groups. But these inputs are not really “free”: using them in one activity (in supporting children with behavioral problems, say) means they are unavailable for other uses (such as a volunteer or parent getting a paid job). In other words, there are opportunity costs.

Services produced from combinations of the resource inputs can be labeled intermediate outputs. They indicate success: Deploying funds to hire staff to deliver services is an achievement in its own right. But they are not the ultimate goals of mental health systems (which are usually expressed in terms of health and quality of life improvement). Relevant questions about these intermediate outputs concern volume (How many therapy sessions are delivered? How many children are supported in a school-based program?), quality of care, and the characteristics of service users (case-mix, in healthcare parlance).

Final outcomes are the focal point of the whole system: symptom alleviation, fewer behavioral problems, improved functioning, educational attainment, and quality of life enhancement. Potentially, there are also outcomes for communities. Some final outcomes take years to reveal themselves fully.

In between services (the intermediate outputs) and outcomes are a number of mediating factors, such as the care-setting social milieu, young people’s care histories, individual and family resilience, and staff attitudes. Although potentially very influential in determining the success of an intervention, they do not have a readily identified cost (since they are not usually marketed) and so they might get overlooked when attention focuses on how services are financed and what they achieve. These can be called nonresource inputs.

This representation was originally called the production of welfare framework (1) and developed to underpin discussion of the economics of care systems because (loose) analogies could be drawn between production processes as studied in mainstream economics and care and support approaches used in health, social services, and education to promote individual and family welfare. There is no suggestion here of mechanistic processes of treatment or care. The stylized framework in Figure 1.6.1 has the signal virtues of highlighting the core connections between what goes in (finances, the resource inputs they purchase, and the unfunded contributions of family members and volunteers) and what comes out (services delivered, and improved outcomes for children, adolescents, and families). And although it looks highly simplified to anyone familiar with psychiatric, education, social services, or justice systems, in fact it is more complicated than often appears to be assumed by strategic decision makers looking for quick fixes. Pumping more money into a system will only generate better outcomes for children, adolescents, and families if all the necessary links are in place and are functioning properly. Thus, revenue generation or collection needs to be planned carefully to avoid creating perverse incentives, and skilled staff need to be supported by other resources if they are to deliver services that families need. Equally, the organization of those services and the therapeutic approaches they employ need to be chosen carefully to maximize the chances of successful resolution. This means looking not only at whether there is evidence of therapeutic effectiveness but also whether it is cost effective.

Succinctly expressed, the success of a child and adolescent mental health system in improving health and quality of life will depend on the mix, volume, and deployment of resource inputs and the services they deliver, which in turn are dependent on available finances.

A Mixed Economy

Child and adolescent mental health services as narrowly defined and conventionally viewed sit in the middle of a complex, multiservice, multibudget world. The reason is simple: Children and adolescents with behavioral or emotional problems and their families often have multiple needs. In well developed, well resourced systems, these needs could be identified, assessed, and addressed by numerous agencies (including pediatrics, child psychiatry, education, social work, and youth justice).

Many examples could be given. Farmer et al. (2) documented the various entry points to, and movement within, part of the U.S. mental health service system: Sixty percent of all youths entered through education, 27% through specialty mental health, and 13% through the general medical sector. Glied and Evans Cuellar (3) describe how 92% of children with serious emotional disturbances in another study received services from more than two systems, and 19% from more than four. In Scotland, 10% of new referrals to child and adolescent psychiatry outpatient services were already under social work supervision (4). Two studies, one in the United States (5) and one in the U.K. (6), illustrate the multiple needs

of children with conduct disorder and the multiple budgets that contribute to meeting them.

of children with conduct disorder and the multiple budgets that contribute to meeting them.

Multiple Provider Sectors

The resources described in Figure 1.6.1 might therefore come from social work, education, housing, employment, criminal justice, or other systems. These services could be delivered by government (public sector), for-profit, or nonprofit organizations. Indeed, most countries have a thriving mixed economy of provision. There are additionally the multifarious contributions of parents, other family caregivers, and volunteers. Even health promotion strategies, which tend to be coordinated by national and local government bodies, still need inputs from others, such as local communities (the social capital effect).

Do these provider distinctions matter? Entities with different legal forms often behave differently in response to incentives, and can be motivated by slightly different goals. For instance, a government hospital may have different objectives and constraints from a for-profit hospital or a charitable hospital linked to a faith community. This may affect their modus operandi, patterns of resource dependency, and styles of governance. Distinctive motivations could influence how they respond to changes in funding levels and routes, market prices for staff or medications, and competition, with implications for costs, case-mix, quality of care, and outcomes (7).

Multiple Funding Sources

Another reason for distinguishing between provider types and the sectors in which they are located is because they are likely to have different funding bases. A treatment facility in the public sector—where most are located in the U.K., for example—is likely to be heavily reliant on tax revenues, whereas a for-profit provider will probably receive more of its funding from insurance plans or user fees. School-based social work services in some countries may be funded through the general education budget, which itself is usually funded through some form of taxation. Services run by nonprofit organizations might be funded under contract or grant from government and by insurance payments, but could also receive charitable donations. Family caregivers, although ostensibly unpaid, might actually receive social security support or disability allowances tied to children’s needs. Matching the diversity in provision, therefore, is a mixed economy of funding.

Interconnections: Transaction Types

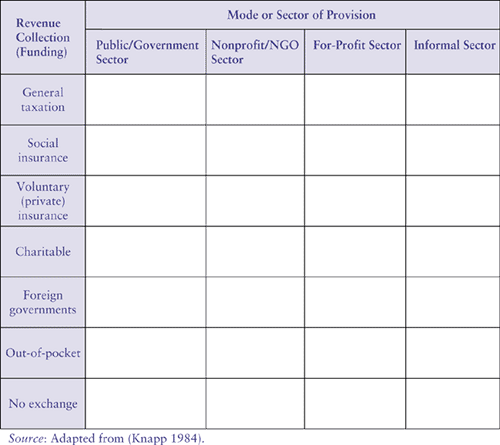

Crossclassifying the main funding and provider types generates a large number of possible interconnections. The matrix in Figure 1.6.2 describes just the broadest categorization of provider sectors and funding sources, but it is already immediately clear that the mixed economy of child mental health care is a highly pluralist system. And each combination of funding arrangement and provider sector could apply to the health, education, social services, criminal justice, and other systems.

There are many transaction types. For example, tax revenues that support for-profit providers could be linked through performance-related contracts, tax breaks, or lump-sum cash subsidies. Insurance payments to providers could be made through fee-for-service, capitation, or other mechanisms. Each transaction type has accompanying needs for regulatory frameworks to control, auditing, and monitoring.

Charting the broad contours of the mixed economy in this way helps to identify the range and volume of services offered to and used by children, adolescents, and families, and the means by which they are funded. It also emphasizes the inherent financial interdependence of different services and

agencies. One recent U.S. study demonstrated how improved community mental health services for young people affected public expenditures in other sectors, “including inpatient hospitalization, the juvenile justice system, the child welfare system, and the special education system. … The full fiscal impact of improved mental health services can be assessed only in the context of their impact on other sectors” (5) (p. 50). Child and adolescent mental health services in England’s national health service allocated as much as 15% of their core budgets to school programs (8). The “expanded school mental health framework” initiated by the U.S. government encourages education services to liaise with community mental health centers, health departments, hospitals, and others to broaden mental health promotion and intervention, although funding is “patchy and tenuous” (9).

agencies. One recent U.S. study demonstrated how improved community mental health services for young people affected public expenditures in other sectors, “including inpatient hospitalization, the juvenile justice system, the child welfare system, and the special education system. … The full fiscal impact of improved mental health services can be assessed only in the context of their impact on other sectors” (5) (p. 50). Child and adolescent mental health services in England’s national health service allocated as much as 15% of their core budgets to school programs (8). The “expanded school mental health framework” initiated by the U.S. government encourages education services to liaise with community mental health centers, health departments, hospitals, and others to broaden mental health promotion and intervention, although funding is “patchy and tenuous” (9).

Coordination

Good interagency coordination is imperative if individual and family needs are to be met, which requires collaborative approaches to financing. Without effective coordination, yawning gaps could open up in the spectrum of support: Even in well resourced care systems there are large numbers of young people whose needs go unrecognized or undertreated. Wasteful duplication of effort is another possibility. Countries, states, and municipalities differ in their service and agency definitions, responsibilities and arrangements, and therefore in their interagency boundaries and the kinds of connected action that spans them. One of the major organizational resource challenges, therefore, is to coordinate the funding of services in ways that are effective, cost-effective, and fair. Cost shifting and problem dumping between agencies will not help children and families, but recognition of economic symbiosis could help decisionmakers fashion improved responses to needs through pooled budgets, jointly commissioned programs, and other whole system initiatives (3,8,10).

Financing Arrangements

Accessing health care services is not like buying groceries, which is why most high- and middle-income countries rely on prepayment systems of revenue collection. Prepayment is organized through tax contributions, social insurance, or private insurance (more accurately labeled voluntary insurance). Prepayment is widely held to be preferable to out-of-pocket payments as the main way to finance health care. An individual’s risk of needing health care is very uncertain, but when the need arises, the attendant costs (of treatment) and losses (of earnings) could be catastrophic. Prepayment contributions pool risks, and have the potential to redistribute benefits toward people with greater health needs. They can also be made progressive, so that poorer individuals pay less for equivalent health care than richer people. Out-of-pocket-payment systems cannot achieve such targeting unless accompanied by well informed systems of payment exemptions that are closely monitored to ensure implementation and prevent abuse.

Prepayment systems have their problems. If there is no charge at the point at which a service is used there may be excessive utilization—the so-called moral hazard problem that might be addressed by introducing copayments at point of use. Another potential difficulty is adverse selection: High-risk individuals are denied coverage or face unaffordable premiums. Additionally, in attempts to cap expenditures, some insurance or managed care arrangements exclude mental health coverage, with predictable consequences for access, knock-on costs, societal inefficiencies, and inequity. Legal intervention, regulation, or subsidy may be needed as countermeasures, or universal coverage guaranteed by public financing (taxation or social insurance) to provide a safety net. Whatever the merits of prepayment systems, there are obstacles to their wider use in low-income countries, including the state of the economy, unstable governance structures, and the informality of much employment. Consequently, out-of-pocket payments

dominate in many low-income countries, where foreign donors may provide significant additional resources, generally in-kind rather than funds.

dominate in many low-income countries, where foreign donors may provide significant additional resources, generally in-kind rather than funds.

Financing can be public or private. Public systems are normally tax based, while private systems include voluntary health insurance (sometimes called private insurance, taken up and paid for at the discretion of individuals) and out-of-pocket payments. Social health insurance systems—common in parts of continental Europe—are quasi-public, as the funding is managed by agencies established by government.

Globally, and looking at health systems as a whole, the most common method of financing is tax based (60%), followed by social insurance (19%), out-of-pocket payments (16%), external grants (3%) and voluntary insurance (2%) (11). As far as mental health systems are concerned, almost every country has a mix of public and private funding.

Two particular questions need to be addressed: What do these various revenue collection arrangements mean for child and adolescent mental health services? And what are the consequences of different commissioning processes (fee-for-service, capitation, and so on) to which they give rise?

Tax-Based Financing

Many health, education, and other systems are funded from national, regional, or local taxes. Income tax is usually described as progressive because it can be structured to capture progressively larger income shares from wealthier individuals. Indirect taxes such as sales tax tend to be regressive, as poorer individuals often contribute larger proportions of their incomes. Tax-based systems of health financing are seen as the most progressive and equitable (12). Payments are mandatory, and scale economies can be achieved in administration, risk management and purchasing power (13). For those who advocate health as a right, taxation-based health systems fit the bill, while those with conservative leanings view such arrangements as an erosion of personal responsibilities and freedom.

Tax-based systems have limitations. Health care funding levels often fluctuate with the state of the national economy: When an economy is not doing well, there is a tendency to cut back on publicly funded programs (10,14). Competing political and economic objectives also make a tax-based system less transparent, and bureaucracy can add to the inefficiency, reflected perhaps in long waiting lists (although these are also symptomatic of underfunding). Patients tend to view tax-based systems as offering them less choice, but uninsured individuals in an alternative financing system might argue that they face no choice whatsoever.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree