Mood Disorders

8.1 Major Depression and Bipolar Disorder

8.1 Major Depression and Bipolar Disorder

Mood can be defined as a pervasive and sustained emotion or feeling tone that influences a person’s behavior and colors his or her perception of being in the world. Disorders of mood—sometimes called affective disorders—make up an important category of psychiatric illness consisting of depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and other disorders, which are discussed in this section and in the section that follows.

A variety of adjectives are used to describe mood: depressed, sad, empty, melancholic, distressed, irritable, disconsolate, elated, euphoric, manic, gleeful, and many others, all descriptive in nature. Some can be observed by the clinician (e.g., an unhappy visage), and others can be felt only by the patient (e.g., hopelessness). Mood can be labile, fluctuating or alternating rapidly between extremes (e.g., laughing loudly and expansively one moment, tearful and despairing the next). Other signs and symptoms of mood disorders include changes in activity level, cognitive abilities, speech, and vegetative functions (e.g., sleep, appetite, sexual activity, and other biological rhythms). These disorders virtually always result in impaired interpersonal, social, and occupational functioning.

It is tempting to consider disorders of mood on a continuum with normal variations in mood. Patients with mood disorders, however, often report an ineffable, but distinct, quality to their pathological state. The concept of a continuum, therefore, may represent the clinician’s overidentification with the pathology, thus possibly distorting his or her approach to patients with mood disorder.

Patients with only major depressive episodes are said to have major depressive disorder or unipolar depression. Patients with both manic and depressive episodes or patients with manic episodes alone are said to have bipolar disorder. The terms “unipolar mania” and “pure mania” are sometimes used for patients who are bipolar but who do not have depressive episodes.

Three additional categories of mood disorders are hypomania, cyclothymia, and dysthymia. Hypomania is an episode of manic symptoms that does not meet the criteria for manic episode. Cyclothymia and dysthymia as disorders that represent less severe forms of bipolar disorder and major depression, respectively.

The field of psychiatry has considered major depression and bipolar disorder to be two separate disorders, particularly in the past 20 years. The possibility that bipolar disorder is actually a more severe expression of major depression has been reconsidered recently, however. Many patients given a diagnosis of a major depressive disorder reveal, on careful examination, past episodes of manic or hypomanic behavior that have gone undetected. Many authorities see considerable continuity between recurrent depressive and bipolar disorders. This has led to widespread discussion and debate about the bipolar spectrum, which incorporates classic bipolar disorder, bipolar II, and recurrent depressions.

HISTORY

The Old Testament story of King Saul describes a depressive syndrome, as does the story of Ajax’s suicide in Homer’s Iliad. About 400 BCE, Hippocrates used the terms mania and melancholia to describe mental disturbances. Around 30 AD, the Roman physician Celsus described melancholia (from Greek melan [“black”] and chole [“bile”]) in his work De re medicina as a depression caused by black bile. The first English text (Fig. 8.1-1) entirely related to depression was Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, published in 1621.

FIGURE 8.1-1

Frontispiece of Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy (1621). (From Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan & Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009.)

In 1854, Jules Falret described a condition called folie circulaire, in which patients experience alternating moods of depression and mania. In 1882, the German psychiatrist Karl Kahlbaum, using the term cyclothymia, described mania and depression as stages of the same illness. In 1899, Emil Kraepelin, building on the knowledge of previous French and German psychiatrists, described manic-depressive psychosis using most of the criteria that psychiatrists now use to establish a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder. According to Kraepelin, the absence of a dementing and deteriorating course in manic-depressive psychosis differentiated it from dementia precox (as schizophrenia was then called). Kraepelin also described a depression that came to be known as involutional melancholia, which has since come to be viewed as a severe form of mood disorder that begins in late adulthood.

Depression

A major depressive disorder occurs without a history of a manic, mixed, or hypomanic episode. A major depressive episode must last at least 2 weeks, and typically a person with a diagnosis of a major depressive episode also experiences at least four symptoms from a list that includes changes in appetite and weight, changes in sleep and activity, lack of energy, feelings of guilt, problems thinking and making decisions, and recurring thoughts of death or suicide.

Mania

A manic episode is a distinct period of an abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood lasting for at least 1 week or less if a patient must be hospitalized. A hypomanic episode lasts at least 4 days and is similar to a manic episode except that it is not sufficiently severe to cause impairment in social or occupational functioning, and no psychotic features are present. Both mania and hypomania are associated with inflated self-esteem, a decreased need for sleep, distractibility, great physical and mental activity, and overinvolvement in pleasurable behavior. Bipolar I disorder is defined as having a clinical course of one or more manic episodes and, sometimes, major depressive episodes. A mixed episode is a period of at least 1 week in which both a manic episode and a major depressive episode occur almost daily. A variant of bipolar disorder characterized by episodes of major depression and hypomania rather than mania is known as bipolar II disorder.

Dysthymia and Cyclothymia

Two additional mood disorders, dysthymic disorder and cyclothymic disorder (discussed fully in Section 8.2) have also been appreciated clinically for some time. Dysthymic disorder and cyclothymic disorder are characterized by the presence of symptoms that are less severe than those of major depressive disorder and bipolar I disorder, respectively. Dysthymic disorder is characterized by at least 2 years of depressed mood that is not sufficiently severe to fit the diagnosis of major depressive episode. Cyclothymic disorder is characterized by at least 2 years of frequently occurring hypomanic symptoms that cannot fit the diagnosis of manic episode and of depressive symptoms that cannot fit the diagnosis of major depressive episode.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Incidence and Prevalence

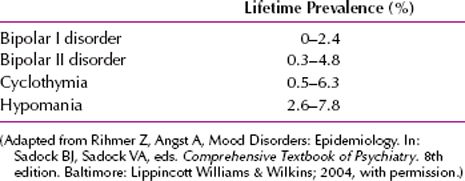

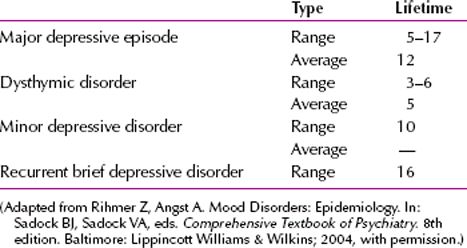

Mood disorders are common. In the most recent surveys, major depressive disorder has the highest lifetime prevalence (almost 17 percent) of any psychiatric disorder. The lifetime prevalence rate of different forms of depressive disorder, according to community surveys, are shown in Table 8.1-1. The lifetime prevalence rate for major depression is 5 to 17 percent. The lifetime prevalence rates of different clinical forms of bipolar disorder are shown in Table 8.1-2. The annual incidence of bipolar illness is considered generally to be less than 1 percent, but it is difficult to estimate because milder forms of bipolar disorder are often missed.

Table 8.1-2

Table 8.1-2

Lifetime Prevalence Rates of Bipolar I Disorder, Bipolar II Disorder, Cyclothymic Disorder, and Hypomania

Table 8.1-1

Table 8.1-1

Lifetime Prevalence Rates of Depressive Disorders

Sex

An almost universal observation, independent of country or culture, is the twofold greater prevalence of major depressive disorder in women than in men. The reasons for the difference are hypothesized to involve hormonal differences, the effects of childbirth, differing psychosocial stressors for women and for men, and behavioral models of learned helplessness. In contrast to major depressive disorder, bipolar I disorder has an equal prevalence among men and women. Manic episodes are more common in men, and depressive episodes are more common in women. When manic episodes occur in women, they are more likely than men to present a mixed picture (e.g., mania and depression). Women also have a higher rate of being rapid cyclers, defined as having four or more manic episodes in a 1-year period.

Age

The onset of bipolar I disorder is earlier than that of major depressive disorder. The age of onset for bipolar I disorder ranges from childhood (as early as age 5 or 6 years) to 50 years or even older in rare cases, with a mean age of 30 years. The mean age of onset for major depressive disorder is about 40 years, with 50 percent of all patients having an onset between the ages of 20 and 50 years. Major depressive disorder can also begin in childhood or in old age. Recent epidemiological data suggest that the incidence of major depressive disorder may be increasing among people younger than 20 years of age. This may be related to the increased use of alcohol and drugs of abuse in this age group.

Marital Status

Major depressive disorder occurs most often in persons without close interpersonal relationships and in those who are divorced or separated. Bipolar I disorder is more common in divorced and single persons than among married persons, but this difference may reflect the early onset and the resulting marital discord characteristic of the disorder.

Socioeconomic and Cultural Factors

No correlation has been found between socioeconomic status and major depressive disorder. A higher than average incidence of bipolar I disorder is found among the upper socioeconomic groups. Bipolar I disorder is more common in persons who did not graduate from college than in college graduates, however, which may also reflect the relatively early age of onset for the disorder. Depression is more common in rural areas than in urban areas. The prevalence of mood disorder does not differ among races. A tendency exists, however, for examiners to underdiagnose mood disorder and overdiagnose schizophrenia in patients whose racial or cultural background differs from theirs.

COMORBIDITY

Individuals with major mood disorders are at an increased risk of having one or more additional comorbid disorders. The most frequent disorders are alcohol abuse or dependence, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and social anxiety disorder. Conversely, individuals with substance use disorders and anxiety disorders also have an elevated risk of lifetime or current comorbid mood disorder. In both unipolar and bipolar disorder, whereas men more frequently present with substance use disorders, women more frequently present with comorbid anxiety and eating disorders. In general, patients who are bipolar more frequently show comorbidity of substance use and anxiety disorders than do patients with unipolar major depression. In the Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study, the lifetime history of substance use disorders, panic disorder, and OCD was approximately twice as high among patients with bipolar I disorder (61 percent, 21 percent, and 21 percent, respectively) than in patients with unipolar major depression (27 percent, 10 percent, and 12 percent, respectively). Comorbid substance use disorders and anxiety disorders worsen the prognosis of the illness and markedly increase the risk of suicide among patients who are unipolar major depressive and bipolar.

ETIOLOGY

Biological Factors

Many studies have reported biological abnormalities in patients with mood disorders. Until recently, the monoamine neurotransmitters—norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin, and histamine—were the main focus of theories and research about the etiology of these disorders. A progressive shift has occurred from focusing on disturbances of single neurotransmitter systems in favor of studying neurobehavioral systems, neural circuits, and more intricate neuroregulatory mechanisms. The monoaminergic systems, thus, are now viewed as broader, neuromodulatory systems, and disturbances are as likely to be secondary or epiphenomenal effects as they are directly or causally related to etiology and pathogenesis.

Biogenic Amines. Of the biogenic amines, norepinephrine and serotonin are the two neurotransmitters most implicated in the pathophysiology of mood disorders.

NOREPINEPHRINE. The correlation suggested by basic science studies between the downregulation or decreased sensitivity of β-adrenergic receptors and clinical antidepressant responses is probably the single most compelling piece of data indicating a direct role for the noradrenergic system in depression. Other evidence has also implicated the presynaptic β2-receptors in depression because activation of these receptors results in a decrease of the amount of norepinephrine released. Presynaptic β2-receptors are also located on serotonergic neurons and regulate the amount of serotonin released. The clinical effectiveness of antidepressant drugs with noradrenergic effects—for example, venlafaxine (Effexor)—further supports a role for norepinephrine in the pathophysiology of at least some of the symptoms of depression.

SEROTONIN. With the huge effect that the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—for example, fluoxetine (Prozac)—have made on the treatment of depression, serotonin has become the biogenic amine neurotransmitter most commonly associated with depression. The identification of multiple serotonin receptor subtypes has also increased the excitement within the research community about the development of even more specific treatments for depression. Besides that SSRIs and other serotonergic antidepressants are effective in the treatment of depression, other data indicate that serotonin is involved in the pathophysiology of depression. Depletion of serotonin may precipitate depression, and some patients with suicidal impulses have low cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations of serotonin metabolites and low concentrations of serotonin uptake sites on platelets.

DOPAMINE. Although norepinephrine and serotonin are the biogenic amines most often associated with the pathophysiology of depression, dopamine has also been theorized to play a role. The data suggest that dopamine activity may be reduced in depression and increased in mania. The discovery of new subtypes of the dopamine receptors and an increased understanding of the presynaptic and postsynaptic regulation of dopamine function have further enriched research into the relation between dopamine and mood disorders. Drugs that reduce dopamine concentrations—for example, reserpine (Serpasil)—and diseases that reduce dopamine concentrations (e.g., Parkinson’s disease) are associated with depressive symptoms. In contrast, drugs that increase dopamine concentrations, such as tyrosine, amphetamine, and bupropion (Wellbutrin), reduce the symptoms of depression. Two recent theories about dopamine and depression are that the mesolimbic dopamine pathway may be dysfunctional in depression and that the dopamine D1 receptor may be hypoactive in depression.

Other Neurotransmitter Disturbances. Acetylcholine (ACh) is found in neurons that are distributed diffusely throughout the cerebral cortex. Cholinergic neurons have reciprocal or interactive relationships with all three monoamine systems. Abnormal levels of choline, which is a precursor to ACh, have been found at autopsy in the brains of some depressed patients, perhaps reflecting abnormalities in cell phospholipid composition. Cholinergic agonist and antagonist drugs have differential clinical effects on depression and mania. Agonists can produce lethargy, anergia, and psychomotor retardation in healthy subjects, can exacerbate symptoms in depression, and can reduce symptoms in mania. These effects generally are not sufficiently robust to have clinical applications, and adverse effects are problematic. In an animal model of depression, strains of mice that are super- or subsensitive to cholinergic agonists have been found susceptible or more resistant to developing learned helplessness (discussed later). Cholinergic agonists can induce changes in hypothalamic–pituitary adrenal (HPA) activity and sleep that mimic those associated with severe depression. Some patients with mood disorders in remission, as well as their never-ill first-degree relatives, have a trait-like increase in sensitivity to cholinergic agonists.

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) has an inhibitory effect on ascending monoamine pathways, particularly the mesocortical and mesolimbic systems. Reductions of GABA have been observed in plasma, CSF, and brain GABA levels in depression. Animal studies have also found that chronic stress can reduce and eventually can deplete GABA levels. By contrast, GABA receptors are upregulated by antidepressants, and some GABAergic medications have weak antidepressant effects.

The amino acids glutamate and glycine are the major excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters in the CNS. Glutamate and glycine bind to sites associated with the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, and an excess of glutamatergic stimulation can cause neurotoxic effects. Importantly, a high concentration of NMDA receptors exists in the hippocampus. Glutamate, thus, may work in conjunction with hypercortisolemia to mediate the deleterious neurocognitive effects of severe recurrent depression. Emerging evidence suggests that drugs that antagonize NMDA receptors have antidepressant effects.

Second Messengers and Intracellular Cascades. The binding of a neurotransmitter and a postsynaptic receptor triggers a cascade of membrane-bound and intracellular processes mediated by second messenger systems. Receptors on cell membranes interact with the intracellular environment via guanine nucleotide-binding proteins (G proteins). The G proteins, in turn, connect to various intracellular enzymes (e.g., adenylate cyclase, phospholipase C, and phosphodiesterase) that regulate utilization of energy and formation of second messengers, such as cyclic nucleotide (e.g., cyclic adenosine monophosphate [cAMP] and cyclic guanosine monophosphate [cGMP]), as well as phosphatidylinositols (e.g., inositol triphosphate and diacylglycerol) and calcium-calmodulin. Second messengers regulate the function of neuronal membrane ion channels. Increasing evidence also indicates that mood-stabilizing drugs act on G proteins or other second messengers.

Alterations of Hormonal Regulation. Lasting alterations in neuroendocrine and behavioral responses can result from severe early stress. Animal studies indicate that even transient periods of maternal deprivation can alter subsequent responses to stress. Activity of the gene coding for the neurokinin brain-derived neurotrophic growth factor (BDNF) is decreased after chronic stress, as is the process of neurogenesis. Protracted stress thus can induce changes in the functional status of neurons and, eventually, cell death. Recent studies in depressed humans indicate that a history of early trauma is associated with increased HPA activity accompanied by structural changes (i.e., atrophy or decreased volume) in the cerebral cortex.

Elevated HPA activity is a hallmark of mammalian stress responses and one of the clearest links between depression and the biology of chronic stress. Hypercortisolema in depression suggests one or more of the following central disturbances: decreased inhibitory serotonin tone; increased drive from norepinephrine, ACh, or corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH); or decreased feedback inhibition from the hippocampus.

Evidence of increased HPA activity is apparent in 20 to 40 percent of depressed outpatients and 40 to 60 percent of depressed inpatients.

Elevated HPA activity in depression has been documented via excretion of urinary-free cortisol (UFC), 24-hour (or shorter time segments) intravenous (IV) collections of plasma cortisol levels, salivary cortisol levels, and tests of the integrity of feedback inhibition. A disturbance of feedback inhibition is tested by administration of dexamethasone (Decadron) (0.5 to 2.0 mg), a potent synthetic glucocorticoid, which normally suppresses HPA axis activity for 24 hours. Nonsuppression of cortisol secretion at 8:00 AM the following morning or subsequent escape from suppression at 4:00 PM or 11:00 PM is indicative of impaired feedback inhibition. Hypersecretion of cortisol and dexamethasone nonsuppression are imperfectly correlated (approximately 60 percent concordance). A more recent development to improve the sensitivity of the test involves infusion of a test dose of CRH after dexamethasone suppression.

These tests of feedback inhibition are not used as a diagnostic test because adrenocortical hyperactivity (albeit usually less prevalent) is observed in mania, schizophrenia, dementia, and other psychiatric disorders.

THYROID AXIS ACTIVITY. Approximately 5 to 10 percent of people evaluated for depression have previously undetected thyroid dysfunction, as reflected by an elevated basal thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level or an increased TSH response to a 500-mg infusion of the hypothalamic neuropeptide thyroid-releasing hormone (TRH). Such abnormalities are often associated with elevated antithyroid antibody levels and, unless corrected with hormone replacement therapy, can compromise response to treatment. An even larger subgroup of depressed patients (e.g., 20 to 30 percent) shows a blunted TSH response to TRH challenge. To date, the major therapeutic implication of a blunted TSH response is evidence of an increased risk of relapse despite preventive antidepressant therapy. Of note, unlike the dexamethasone-suppression test (DST), blunted TSH response to TRH does not usually normalize with effective treatment.

GROWTH HORMONE. Growth hormone (GH) is secreted from the anterior pituitary after stimulation by NE and dopamine. Secretion is inhibited by somatostatin, a hypothalamic neuropeptide, and CRH. Decreased CSF somatostatin levels have been reported in depression, and increased levels have been observed in mania.

PROLACTIN. Prolactin is released from the pituitary by serotonin stimulation and inhibited by dopamine. Most studies have not found significant abnormalities of basal or circadian prolactin secretion in depression, although a blunted prolactin response to various serotonin agonists has been described. This response is uncommon among premenopausal women, suggesting that estrogen has a moderating effect.

Alterations of Sleep Neurophysiology. Depression is associated with a premature loss of deep (slow-wave) sleep and an increase in nocturnal arousal. The latter is reflected by four types of disturbance: (1) an increase in nocturnal awakenings, (2) a reduction in total sleep time, (3) increased phasic rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, and (4) increased core body temperature. The combination of increased REM drive and decreased slow-wave sleep results in a significant reduction in the first period of non-REM (NREM) sleep, a phenomenon referred to as reduced REM latency. Reduced REM latency and deficits of slow-wave sleep typically persist after recovery of a depressive episode. Blunted secretion of GH after sleep onset is associated with decreased slow-wave sleep and shows similar state-independent or trait-like behavior. The combination of reduced REM latency, increased REM density, and decreased sleep maintenance identifies approximately 40 percent of depressed outpatients and 80 percent of depressed inpatients. False-negative findings are commonly seen in younger, hypersomnolent patients, who may actually experience an increase in slow-wave sleep during episodes of depression. Approximately 10 percent of otherwise healthy individuals have abnormal sleep profiles, and, as with dexamethasone nonsuppression, false-positive cases are not uncommonly seen in other psychiatric disorders.

Patients manifesting a characteristically abnormal sleep profile have been found to be less responsive to psychotherapy and to have a greater risk of relapse or recurrence and may benefit preferentially from pharmacotherapy.

Immunological Disturbance. Depressive disorders are associated with several immunological abnormalities, including decreased lymphocyte proliferation in response to mitogens and other forms of impaired cellular immunity. These lymphocytes produce neuromodulators, such as corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), and cytokines, peptides known as interleukins. There appears to be an association with clinical severity, hypercortisolism, and immune dysfunction, and the cytokine interleukin-1 may induce gene activity for glucocorticoid synthesis.

Structural and Functional Brain Imaging. Computed axial tomography (CAT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans have permitted sensitive, noninvasive methods to assess the living brain, including cortical and subcortical tracts, as well as white matter lesions. The most consistent abnormality observed in the depressive disorders is increased frequency of abnormal hyperintensities in subcortical regions, such as periventricular regions, the basal ganglia, and the thalamus. More common in bipolar I disorder and among elderly adults, these hyperintensities appear to reflect the deleterious neurodegenerative effects of recurrent affective episodes. Ventricular enlargement, cortical atrophy, and sulcal widening also have been reported in some studies. Some depressed patients also may have reduced hippocampal or caudate nucleus volumes, or both, suggesting more focal defects in relevant neurobehavioral systems. Diffuse and focal areas of atrophy have been associated with increased illness severity, bipolarity, and increased cortisol levels.

The most widely replicated positron emission tomography (PET) finding in depression is decreased anterior brain metabolism, which is generally more pronounced on the left side. From a different vantage point, depression may be associated with a relative increase in nondominant hemispheric activity. Furthermore, a reversal of hypofrontality occurs after shifts from depression into hypomania, such that greater left hemisphere reductions are seen in depression compared with greater right hemisphere reductions in mania. Other studies have observed more specific reductions of reduced cerebral blood flow or metabolism, or both, in the dopaminergically innervated tracts of the mesocortical and mesolimbic systems in depression. Again, evidence suggests that antidepressants at least partially normalize these changes.

In addition to a global reduction of anterior cerebral metabolism, increased glucose metabolism has been observed in several limbic regions, particularly among patients with relatively severe recurrent depression and a family history of mood disorder. During episodes of depression, increased glucose metabolism is correlated with intrusive ruminations.

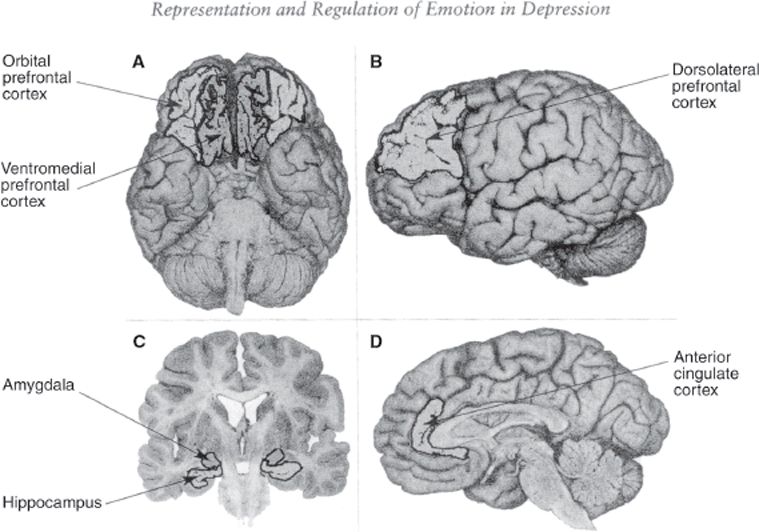

Neuroanatomical Considerations. Both the symptoms of mood disorders and biological research findings support the hypothesis that mood disorders involve pathology of the brain. Modern affective neuroscience focuses on the importance of four brain regions in the regulation of normal emotions: the prefrontal cortex (PFC), the anterior cingulate, the hippocampus, and the amygdala. The PFC is viewed as the structure that holds representations of goals and appropriate responses to obtain these goals. Such activities are particularly important when multiple, conflicting behavioral responses are possible or when it is necessary to override affective arousal. Evidence indicates some hemispherical specialization in PFC function. For example, whereas left-sided activation of regions of the PFC is more involved in goal-directed or appetitive behaviors, regions of the right PFC are implicated in avoidance behaviors and inhibition of appetitive pursuits. Subregions in the PFC appear to localize representations of behaviors related to reward and punishment.

The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is thought to serve as the point of integration of attentional and emotional inputs. Two subdivisions have been identified: an affective subdivision in the rostral and ventral regions of the ACC and a cognitive subdivision involving the dorsal ACC. The former subdivision shares extensive connections with other limbic regions, and the latter interacts more with the PFC and other cortical regions. It is proposed that activation of the ACC facilitates control of emotional arousal, particularly when goal attainment has been thwarted or when novel problems have been encountered.

The hippocampus is most clearly involved in various forms of learning and memory, including fear conditioning, as well as inhibitory regulation of the HPA axis activity. Emotional or contextual learning appears to involve a direct connection between the hippocampus and the amygdala.

The amygdala appears to be a crucial way station for processing novel stimuli of emotional significance and coordinating or organizing cortical responses. Located just above the hippocampi bilaterally, the amygdala has long been viewed as the heart of the limbic system. Although most research has focused on the role of the amygdala in responding to fearful or painful stimuli, it may be ambiguity or novelty, rather than the aversive nature of the stimulus per se, that brings the amygdala on line (Fig. 8.1-2).

FIGURE 8.1-2

Key brain regions involved in affect and mood disorders. A. Orbital prefrontal cortex and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. B. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. C. Hippocampus and amygdala. D. Anterior cingulate cortex. (From Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan & Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009.)

Genetic Factors

Numerous family, adoption, and twin studies have long documented the heritability of mood disorders. Recently, however, the primary focus of genetic studies has been to identify specific susceptibility genes using molecular genetic methods.

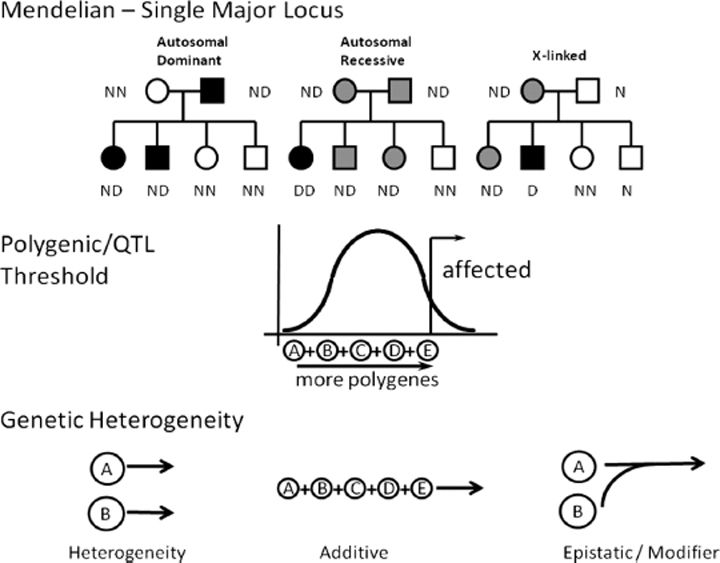

Family Studies. Family studies address the question of whether a disorder is familial. More specifically, is the rate of illness in the family members of someone with the disorder greater than that of the general population? Family data indicate that if one parent has a mood disorder, a child will have a risk of between 10 and 25 percent for mood disorder. If both parents are affected, this risk roughly doubles. The more members of the family who are affected, the greater the risk is to a child. The risk is greater if the affected family members are first-degree relatives rather than more distant relatives. A family history of bipolar disorder conveys a greater risk for mood disorders in general and, specifically, a much greater risk for bipolar disorder. Unipolar disorder is typically the most common form of mood disorder in families of bipolar probands. This familial overlap suggests some degree of common genetic underpinnings between these two forms of mood disorder. The presence of more severe illness in the family also conveys a greater risk (Fig. 8.1-3).

FIGURE 8.1-3

Many different models of genetic transmission have been considered and tested to see if they would explain the transmission of mood disorders. This is a selection of some of the more prominent models. In Mendelian or single major locus transmission, one gene transmits the illness. In polygenic quantitative trait (QTL) model, multiple genes add together to contribute to a quantitative trait. In this figure, the X axis represents the number of polygenes that a given individual is carrying, as well as the value of the resulting quantitative trait. The frequency of that trait value in the population is represented on the axis represents the number of polygenes that a given individual is carrying, as well as the value of the resulting quantitative trait. The frequency of that trait value in the population is represented on the Y axis. In the bottom panel, some possible models or genetic heterogeneity are illustrated. (From Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan & Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009.)

Adoption Studies. Adoption studies provide an alternative approach to separating genetic and environmental factors in familial transmission. Only a limited number of such studies have been reported, and their results have been mixed. One large study found a threefold increase in the rate of bipolar disorder and a twofold increase in unipolar disorder in the biological relatives of bipolar probands. Similarly, in a Danish sample, a threefold increase in the rate of unipolar disorder and a sixfold increase in the rate of completed suicide in the biological relatives of affectively ill probands were reported. Other studies, however, have been less convincing and have found no difference in the rates of mood disorders.

Twin Studies. Twin studies provide the most powerful approach to separating genetic from environmental factors, or “nature” from “nurture.” The twin data provide compelling evidence that genes explain only 50 to 70 percent of the etiology of mood disorders. Environment or other nonheritable factors must explain the remainder. Therefore, it is a predisposition or susceptibility to disease that is inherited. Considering unipolar and bipolar disorders together, these studies find a concordance rate for mood disorder in the monozygotic (MZ) twins of 70 to 90 percent compared with the same-sex dizygotic (DZ) twins of 16 to 35 percent. This is the most compelling data for the role of genetic factors in mood disorders.

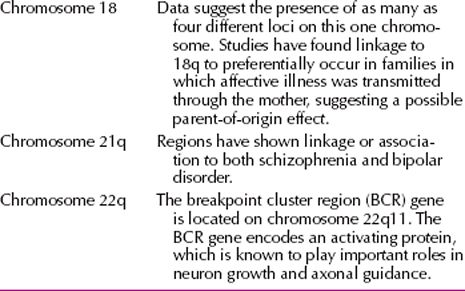

Linkage Studies. DNA markers are segments of DNA of known chromosomal location, which are highly variable among individuals. They are used to track the segregation of specific chromosomal regions within families affected with a disorder. When a marker is identified with disease in families, the disease is said to be genetically linked (Table 8.1-3). Chromosomes 18q and 22q are the two regions with strongest evidence for linkage to bipolar disorder. Several linkage studies have found evidence for the involvement of specific genes in clinical subtypes. For example, the linkage evidence on 18q has been shown to be derived largely from bipolar II–bipolar II sibling pairs and from families in which the probands had panic symptoms.

Table 8.1-3

Table 8.1-3

Selected Chromosomal Regions with Evidence of Linkage to Bipolar Disorder

Gene-mapping studies of unipolar depression have found very strong evidence of linkage to the locus for cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB1) on chromosome 2. Eighteen other genomic regions were found to be linked; some of these displayed interactions with the CREB1 locus. Another study has reported evidence for a gene–environment interaction in the development of major depression. Subjects who underwent adverse life events were shown, in general, to be at an increased risk for depression. Of such subjects, however, those with a variant in the serotonin transporter gene showed the greatest increase in risk. This is one of the first reports of a specific gene–environment interaction in a psychiatric disorder.

Psychosocial Factors

Life Events and Environmental Stress. A long-standing clinical observation is that stressful life events more often precede first, rather than subsequent, episodes of mood disorders. This association has been reported for both patients with major depressive disorder and patients with bipolar I disorder. One theory proposed to explain this observation is that the stress accompanying the first episode results in long-lasting changes in the brain’s biology. These long-lasting changes may alter the functional states of various neurotransmitter and intraneuronal signaling systems, changes that may even include the loss of neurons and an excessive reduction in synaptic contacts. As a result, a person has a high risk of undergoing subsequent episodes of a mood disorder, even without an external stressor.

Some clinicians believe that life events play the primary or principal role in depression; others suggest that life events have only a limited role in the onset and timing of depression. The most compelling data indicate that the life event most often associated with development of depression is losing a parent before age 11 years. The environmental stressor most often associated with the onset of an episode of depression is the loss of a spouse. Another risk factor is unemployment; persons out of work are three times more likely to report symptoms of an episode of major depression than those who are employed. Guilt may also play a role.

Ms. C, a 23-year-old woman, became acutely depressed when she was accepted to a prestigious graduate school. Ms. C had been working diligently toward this acceptance for the past 4 years. She reported being “briefly happy, for about 20 minutes” when she learned the good news but rapidly slipped into a hopeless state in which she recurrently pondered the pointlessness of her aspirations, cried constantly, and had to physically stop herself from taking a lethal overdose of her roommate’s insulin. In treatment, she focused on her older brother, who had regularly insulted her throughout the course of her life, and how “he’s not doing well.” She found herself very worried about him. She mentioned that she was not used to being the “successful” one of the two of them. In connection with her depression, it emerged that Ms. C’s brother had had a severe, life-threatening, and disfiguring pediatric illness that had required much family time and attention throughout their childhood. Ms. C had become “used to” his insulting manner toward her. In fact, it seemed that she required her brother’s abuse of her in order not to feel overwhelmed by survivor guilt about being the “healthy, normal” child. “He might insult me, but I look up to him. I adore him. Any attention he pays to me is like a drug,” she said. Ms. C’s acceptance to graduate school had challenged her defensive and essential compensatory image of herself as being less successful, or damaged, in comparison with her brother, thereby overwhelming her with guilt. Her depression remitted in psychodynamic psychotherapy as she better understood her identification with and fantasy submission to her brother. (Courtesy of JC Markowitz, M.D., and BL Milrod, M.D.)

Personality Factors. No single personality trait or type uniquely predisposes a person to depression; all humans, of whatever personality pattern, can and do become depressed under appropriate circumstances. Persons with certain personality disorders—OCD, histrionic, and borderline—may be at greater risk for depression than persons with antisocial or paranoid personality disorder. The latter can use projection and other externalizing defense mechanisms to protect themselves from their inner rage. No evidence indicates that any particular personality disorder is associated with later development of bipolar I disorder; however, patients with dysthymic disorder and cyclothymic disorder are at risk of later developing major depression or bipolar I disorder.

Recent stressful events are the most powerful predictors of the onset of a depressive episode. From a psychodynamic perspective, the clinician is always interested in the meaning of the stressor. Research has demonstrated that stressors that the patient experiences as reflecting negatively on his or her self-esteem are more likely to produce depression. Moreover, what may seem to be a relatively mild stressor to outsiders may be devastating to the patient because of particular idiosyncratic meanings attached to the event.

Psychodynamic Factors in Depression. The psychodynamic understanding of depression defined by Sigmund Freud and expanded by Karl Abraham is known as the classic view of depression. That theory involves four key points: (1) disturbances in the infant–mother relationship during the oral phase (the first 10 to 18 months of life) predispose to subsequent vulnerability to depression; (2) depression can be linked to real or imagined object loss; (3) introjection of the departed objects is a defense mechanism invoked to deal with the distress connected with the object’s loss; and (4) because the lost object is regarded with a mixture of love and hate, feelings of anger are directed inward at the self.

Ms. E, a 21-year-old college student, presented with major depression and panic disorder since early adolescence. She reported hating herself, crying constantly, and feeling profoundly hopeless in part because of the chronicity of her illness. Even at the time of presentation, she noted her sensitivity to her mother’s moods. “My mother’s just always depressed, and it makes me so miserable. I just don’t know what to do,” she said. “I always want something from her, I don’t even know what, but I never get it. She always says the wrong thing, talks about how disturbed I am, stuff like that, makes me feel bad about myself.” In one session, Ms. E poignantly described her childhood: “I spent a lot of time with my mother, but she was always too tired, she never wanted to do anything or play with me. I remember building a house with blankets over the coffee table and peeking out, spying on her. She was always depressed and negative, like a negative sink in the room, making it empty and sad. I could never get her to do anything.” This patient experienced extreme guilt in her psychotherapy when she began to talk about her mother’s depression. “I feel so bad,” she sobbed. “It’s like I’m saying bad things about her. And I love her so much, and I know she loves me. I feel it’s so disloyal of me.” Her depression remitted in psychodynamic psychotherapy as she became more aware of and better able to tolerate her feelings of rage and disappointment with her mother. (Courtesy of JC Markowitz, M.D., and BL Milrod, M.D.)

Melanie Klein understood depression as involving the expression of aggression toward loved ones, much as Freud did. Edward Bibring regarded depression as a phenomenon that sets in when a person becomes aware of the discrepancy between extraordinarily high ideals and the inability to meet those goals. Edith Jacobson saw the state of depression as similar to a powerless, helpless child victimized by a tormenting parent. Silvano Arieti observed that many depressed people have lived their lives for someone else rather than for themselves. He referred to the person for whom depressed patients live as the dominant other, which may be a principle, an ideal, or an institution, as well as an individual. Depression sets in when patients realize that the person or ideal for which they have been living is never going to respond in a manner that will meet their expectations. Heinz Kohut’s conceptualization of depression, derived from his self-psychological theory, rests on the assumption that the developing self has specific needs that must be met by parents to give the child a positive sense of self-esteem and self-cohesion. When others do not meet these needs, there is a massive loss of self-esteem that presents as depression. John Bowlby believed that damaged early attachments and traumatic separation in childhood predispose to depression. Adult losses are said to revive the traumatic childhood loss and so precipitate adult depressive episodes.

Psychodynamic Factors in Mania. Most theories of mania view manic episodes as a defense against underlying depression. Abraham, for example, believed that the manic episodes may reflect an inability to tolerate a developmental tragedy, such as the loss of a parent. The manic state may also result from a tyrannical superego, which produces intolerable self-criticism that is then replaced by euphoric self-satisfaction. Bertram Lewin regarded the manic patient’s ego as overwhelmed by pleasurable impulses, such as sex, or by feared impulses, such as aggression. Klein also viewed mania as a defensive reaction to depression, using manic defenses such as omnipotence, in which the person develops delusions of grandeur.

Ms. G, a 42-year-old housewife and mother of a 4-year-old boy, developed symptoms of hypomania and later of frank mania without psychosis, when her only son was diagnosed with acute lymphocytic leukemia. A profoundly religious woman who had experienced 10 years of difficulty with conception, Ms. G was a devoted mother. She reported that she was usually rather down. Before her son’s illness, she used to joke that she had become pregnant with him by divine intervention. When her son was diagnosed and subsequently hospitalized, he required painful medical tests and emergency chemotherapy, which made him very ill. The doctors regularly barraged Ms. G with bad news about his prognosis during the first few weeks of his illness.

Ms. G was ever present with her son at the hospital, never sleeping, always caring for him, yet the pediatricians noted that as the child became more debilitated and the prognosis more grim, she seemed to bubble over with renewed cheerfulness, good humor, and high spirits. She could not seem to stop herself from cracking jokes to the hospital staff during her son’s painful procedures, and as the jokes became louder and more inappropriate, the staff grew more concerned. During her subsequent psychiatric consultation (requested by the pediatric staff), Ms. G reported that her current “happiness and optimism” were justified by her sense of “oneness” with Mary, the mother of God. “We are together now, she and I, and she has become a part of me. We have a special relationship,” she winked. Despite these statements, Ms. G was not psychotic and said that she was “speaking metaphorically, of course, only as a good Catholic would.” Her mania resolved when her son achieved remission and was discharged from the hospital. (Courtesy of JC Markowitz, M.D., and BL Milrod, M.D.)

Other Formulations of Depression

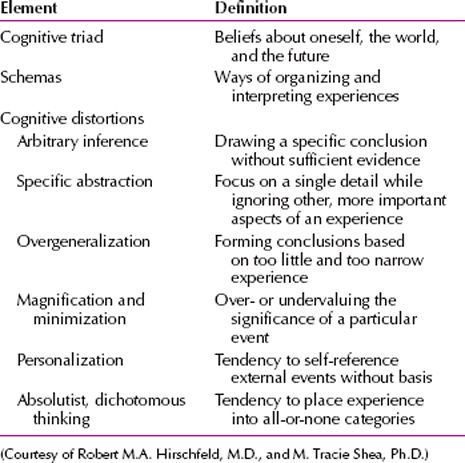

Cognitive Theory. According to cognitive theory, depression results from specific cognitive distortions present in persons susceptible to depression. These distortions, referred to as depressogenic schemata, are cognitive templates that perceive both internal and external data in ways that are altered by early experiences. Aaron Beck postulated a cognitive triad of depression that consists of (1) views about the self—a negative self-precept, (2) about the environment—a tendency to experience the world as hostile and demanding, and (3) about the future—the expectation of suffering and failure. Therapy consists of modifying these distortions. The elements of cognitive theory are summarized in Table 8.1-4.

Table 8.1-4

Table 8.1-4

Elements of Cognitive Theory

Learned Helplessness. The learned helplessness theory of depression connects depressive phenomena to the experience of uncontrollable events. For example, when dogs in a laboratory were exposed to electrical shocks from which they could not escape, they showed behaviors that differentiated them from dogs that had not been exposed to such uncontrollable events. The dogs exposed to the shocks would not cross a barrier to stop the flow of electric shock when put in a new learning situation. They remained passive and did not move. According to the learned helplessness theory, the shocked dogs learned that outcomes were independent of responses, so they had both cognitive motivational deficit (i.e., they would not attempt to escape the shock) and emotional deficit (indicating decreased reactivity to the shock). In the reformulated view of learned helplessness as applied to human depression, internal causal explanations are thought to produce a loss of self-esteem after adverse external events. Behaviorists who subscribe to the theory stress that improvement of depression is contingent on the patient’s learning a sense of control and mastery of the environment.

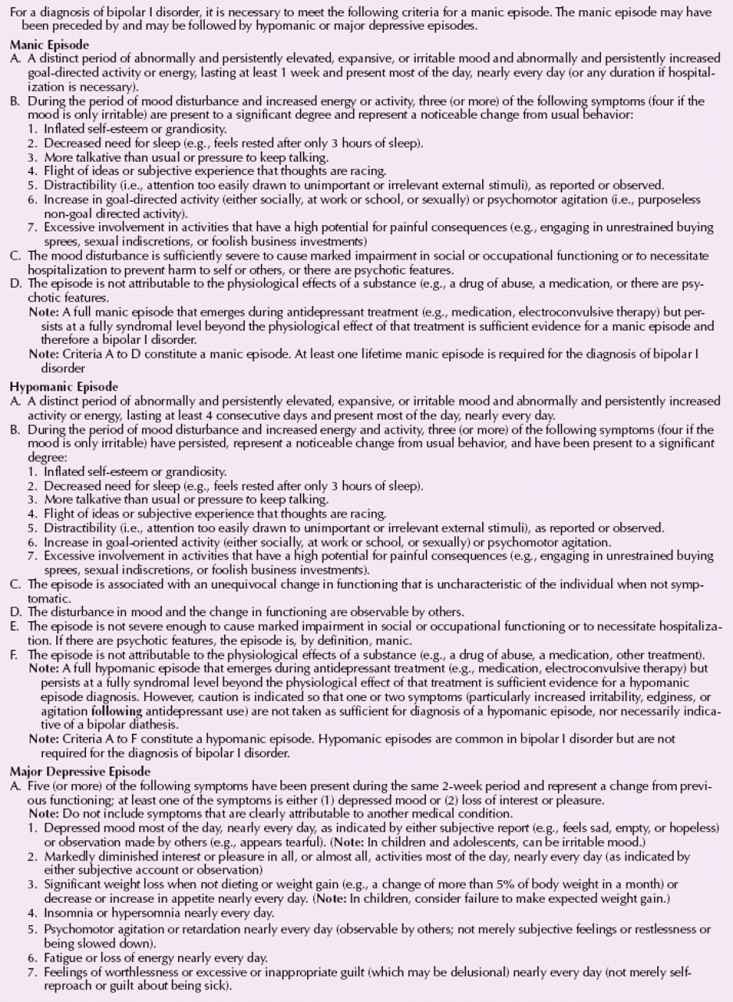

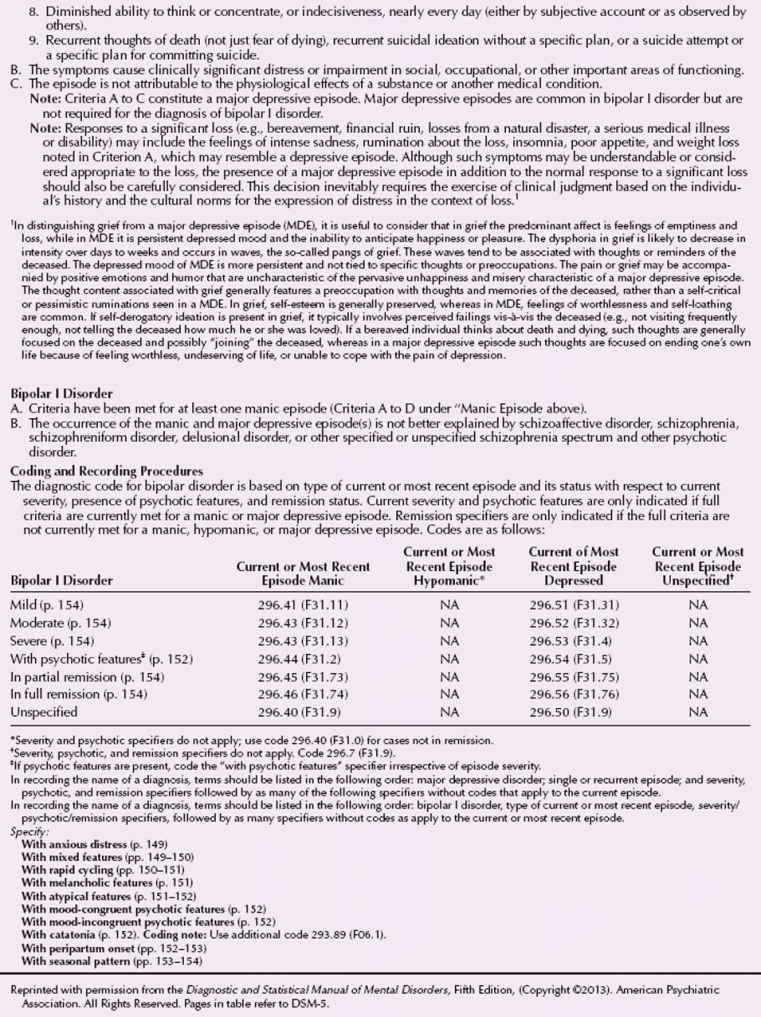

DIAGNOSIS

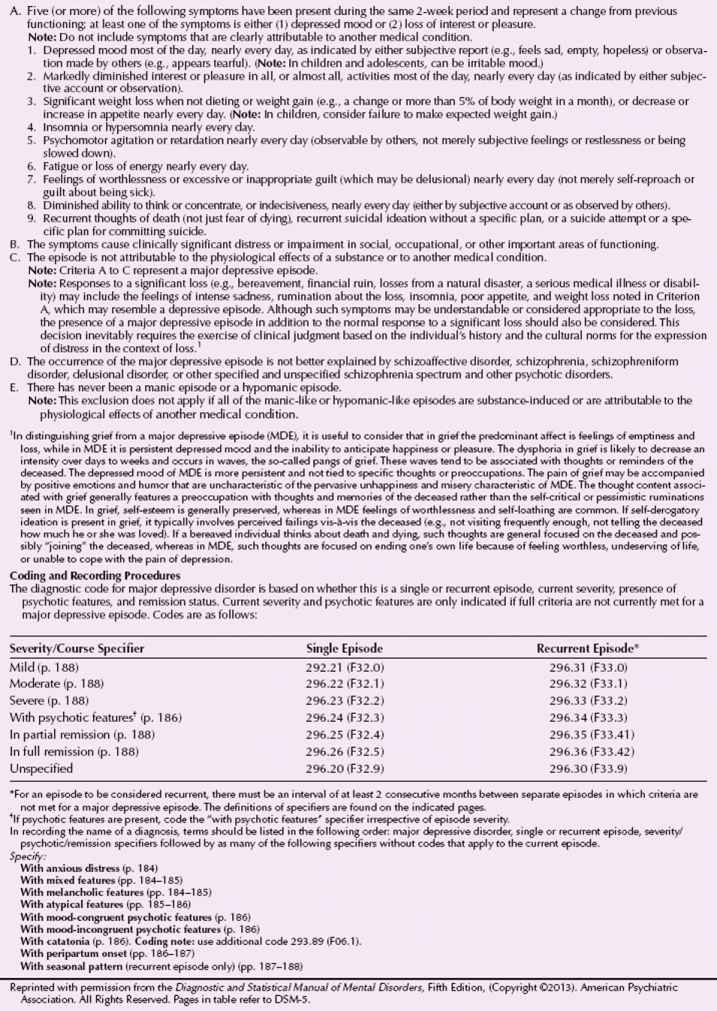

Major Depressive Disorder

The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for major depression are listed in Table 8.1-5; severity descriptors and other specifiers for a major depressive episode are also listed in that table.

Table 8.1-5

Table 8.1-5

DSM-5 Criteria for Major Depressive Disorder

Major Depressive Disorder, Single Episode

Depression may occur as a single episode or may be recurrent. Differentiation between these patients and those who have two or more episodes of major depressive disorder is justified because of the uncertain course of the former patients’ disorder. Several studies have reported data consistent with the notion that major depression covers a heterogeneous population of disorders. One type of study assessed the stability of a diagnosis of major depression in a patient over time. The study found that 25 to 50 percent of the patients were later reclassified as having a different psychiatric condition or a nonpsychiatric medical condition with psychiatric symptoms. A second type of study evaluated first-degree relatives of affectively ill patients to determine the presence and types of psychiatric diagnoses for these relatives over time. Both types of studies found that depressed patients with more depressive symptoms are more likely to have stable diagnoses over time and are more likely to have affectively ill relatives than are depressed patients with fewer depressive symptoms. Also, patients with bipolar I disorder and those with bipolar II disorder (recurrent major depressive episodes with hypomania) are likely to have stable diagnoses over time.

Major Depressive Disorder, Recurrent

Patients who are experiencing at least a second episode of depression are classified as having major depressive disorder, recurrent. The essential problem with diagnosing recurrent episodes of major depressive disorder is choosing the criteria to designate the resolution of each period. Two variables are the degree of resolution of the symptoms and the length of the resolution. DSM-5 requires that distinct episodes of depression be separated by at least 2 months during which a patient has no significant symptoms of depression.

Bipolar I Disorder

The DSM-5 criteria for a bipolar I disorder (Table 8.1-6) requires the presence of a distinct period of abnormal mood lasting at least 1 week and includes separate bipolar I disorder diagnoses for a single manic episode and a recurrent episode based on the symptoms of the most recent episode as described below.

Table 8.1-6

Table 8.1-6

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Bipolar I Disorder

The designation bipolar I disorder is synonymous with what was formerly known as bipolar disorder—a syndrome in which a complete set of mania symptoms occurs during the course of the disorder. The diagnostic criteria for bipolar II disorder is characterized by depressive episodes and hypomanic episodes during the course of the disorder, but the episodes of manic-like symptoms do not quite meet the diagnostic criteria for a full manic syndrome.

Manic episodes clearly precipitated by antidepressant treatment (e.g., pharmacotherapy, electroconvulsive therapy [ECT]) do not indicate bipolar I disorder.

Bipolar I Disorder, Single Manic Episode. According to DSM-5, patients must be experiencing their first manic episode to meet the diagnostic criteria for bipolar I disorder, single manic episode. This requirement rests on the fact that patients who are having their first episode of bipolar I disorder depression cannot be distinguished from patients with major depressive disorder.

Bipolar I Disorder, Recurrent. The issues about defining the end of an episode of depression also apply to defining the end of an episode of mania. Manic episodes are considered distinct when they are separated by at least 2 months without significant symptoms of mania or hypomania.

Bipolar II Disorder

The diagnostic criteria for bipolar II disorder specify the particular severity, frequency, and duration of the hypomanic symptoms. The diagnostic criteria for a hypomanic episode are listed together with the criteria for bipolar II disorder (also in Table 8.1-6). The criteria have been established to decrease overdiagnosis of hypomanic episodes and the incorrect classification of patients with major depressive disorder as patients with bipolar II disorder. Clinically, psychiatrists may find it difficult to distinguish euthymia from hypomania in a patient who has been chronically depressed for many months or years. As with bipolar I disorder, antidepressant-induced hypomanic episodes are not diagnostic of bipolar II disorder.

Specifiers (Symptom Features)

In addition to the severity, psychotic, and remission descriptions, additional symptom features (specifiers) can be used to describe patients with various mood disorders.

With Psychotic Features. The presence of psychotic features in major depressive disorder reflects severe disease and is a poor prognostic indicator. A review of the literature comparing psychotic with nonpsychotic major depressive disorder indicates that the two conditions may be distinct in their pathogenesis. One difference is that bipolar I disorder is more common in the families of probands with psychotic depression than in the families of probands with nonpsychotic depression.

The psychotic symptoms themselves are often categorized as either mood congruent, that is, in harmony with the mood disorder (“I deserve to be punished because I am so bad”), or mood incongruent, not in harmony with the mood disorder. Patients with mood disorder with mood-congruent psychoses have a psychotic type of mood disorder; however, patients with mood disorder with mood-incongruent psychotic symptoms may have schizoaffective disorder or schizophrenia.

The following factors have been associated with a poor prognosis for patients with mood disorders: long duration of episodes, temporal dissociation between the mood disorder and the psychotic symptoms, and a poor premorbid history of social adjustment. The presence of psychotic features also has significant treatment implications. These patients typically require antipsychotic drugs in addition to antidepressants or mood stabilizers and may need ECT to obtain clinical improvement.

With Melancholic Features. Melancholia is one of the oldest terms used in psychiatry, dating back to Hippocrates in the 4th century to describe the dark mood of depression. It is still used to refer to a depression characterized by severe anhedonia, early morning awakening, weight loss, and profound feelings of guilt (often over trivial events). It is not uncommon for patients who are melancholic to have suicidal ideation. Melancholia is associated with changes in the autonomic nervous system and in endocrine functions. For that reason, melancholia is sometimes referred to as “endogenous depression” or depression that arises in the absence of external life stressors or precipitants. The DSM-5 melancholic features can be applied to major depressive episodes in major depressive disorder, bipolar I disorder, or bipolar II disorder.

With Atypical Features. The introduction of a formally defined depression with atypical features is a response to research and clinical data indicating that patients with atypical features have specific, predictable characteristics: overeating and oversleeping. These symptoms have sometimes been referred to as reversed vegetative symptoms, and the symptom pattern has sometimes been called hysteroid dysphoria. When patients with major depressive disorder with atypical features are compared with patients with typical depression features, the patients with atypical features are found to have a younger age of onset; more severe psychomotor slowing; and more frequent coexisting diagnoses of panic disorder, substance abuse or dependence, and somatization disorder. The high incidence and severity of anxiety symptoms in patients with atypical features have sometimes been correlated with the likelihood of their being misclassified as having an anxiety disorder rather than a mood disorder. Patients with atypical features may also have a long-term course, a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, or a seasonal pattern to their disorder.

The DSM-5 atypical features can be applied to the most recent major depressive episode in major depressive disorder, bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, or dysthymic disorder. Atypical depression may mask manic symptoms as in the following case.

Kevin, a 15-year-old adolescent, was referred to a sleep center to rule out narcolepsy. His main complaints were fatigue, boredom, and a need to sleep all the time. Although he had always started the day somewhat slowly, he now could not get out of bed to go to school. That alarmed his mother, prompting sleep consultation. Formerly a B student, he had been failing most of his courses in the 6 months before referral. Psychological counseling, predicated on the premise that his family’s recent move from another city had led to Kevin’s isolation, had not been beneficial. Extensive neurological and general medical workup findings had also proven negative. He slept 12 to 15 hours per day but denied cataplexy, sleep paralysis, and hypnagogic hallucinations. During psychiatric interview, he denied being depressed but admitted that he had lost interest in everything except his dog. He had no drive, participated in no activities, and had gained 30 pounds in 6 months. He believed that he was “brain damaged” and wondered whether it was worth living like that. The question of suicide disturbed him because it was contrary to his religious beliefs. These findings led to the prescription of desipramine (Norpramin) in a dosage that was gradually increased to 200 mg per day over 3 weeks. Not only did desipramine reverse the presenting complaints, but it also pushed him to the brink of a manic episode. (Courtesy of HS Akiskal, M.D.)

With Catatonic Features. As a symptom, catatonia can be present in several mental disorders, most commonly, schizophrenia and the mood disorders. The presence of catatonic features in patients with mood disorders may have prognostic and treatment significance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree