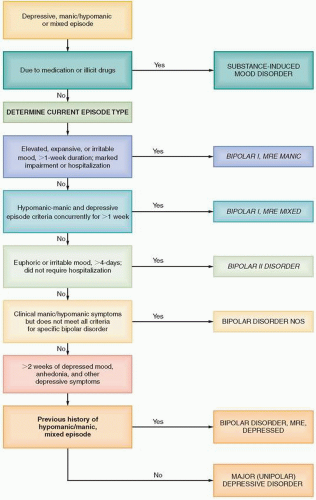

The “building blocks” for both bipolar spectrum disorders include depressive, hypomanic, manic, and mixed episodes. Patients with bipolar disorder I must have had at least one manic or mixed episode and those with bipolar II must have had at least one depressive and one hypomanic episode. The principle difference between a manic and a hypomanic episode is that the former must result in significant social or occupational dysfunction or need for psychiatric admission.

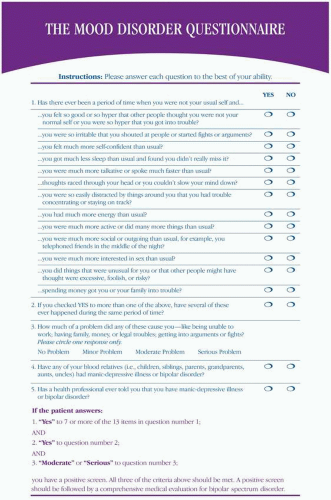

Most patients with bipolar disorder present with depression, so it is important to screen for bipolar disorder in all patients who present with depressive symptoms.

The classic presentation of bipolar mania may be absent in many patients. There is a delay in an accurate diagnosis of bipolar disorder that averages about 8 years after the initial presentation to a mental health professional.

Up to 30% of depressed and anxious patients who present to primary care settings may have an underlying bipolar disorder.

Bipolar disorder is a chronic disease with an episodic, relapsing-remitting condition that requires long-term treatment.

Bipolar disorder occurs frequently with substance use disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

The contemporary treatment of bipolar acute manic or mixed states involves the use of combination therapy with a mood stabilizer and a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA).

Treatment options for bipolar depression include lamotrigine, lithium, quetiapine, and an antidepressant combined with a mood stabilizer or SGA. As a general rule, antidepressants should not be used as monotherapy to treat a bipolar spectrum disorder.

Table 3.1 DSM-IV-TR Criteria for a Manic Episode | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 3.2 Screening Questions for Manic and Hypomanic Episodes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

be grandiose or delusional and themes of exaggerated power and achievement are often present.

Figure 3.1. The mood disorder questionnaire (6). (© 2000 by American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. Reprinted with permission. This instrument is designed for screening purposes only and is not to be used as a diagnostic tool.) |

distinguish from a primary mood disorder. Therefore, it is important to inquire about the existence of any mood disturbances during periods of sobriety.

Table 3.3 Medications and Medical Conditions Associated with Mood Disturbances | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

the treatment for bipolar disorder (10). Manic episodes frequently require psychiatric hospitalization. For acute bipolar mania, a mood stabilizer (except lamotrigine) is generally indicated in combination with an SGA (11). SGAs have FDA approval for acute bipolar manic and mixed episodes (Table 3.5). For bipolar depression, lamotrigine, lithium, quetiapine, and an antidepressant combined with a mood stabilizer or an SGA are possible options. There is currently no FDA-approved medication

specifically for the treatment of bipolar II disorder, per se. The hypomania of bipolar II may be treated with a mood stabilizer and/or an SGA. The approach to the treatment of depression is similar for both bipolar I and bipolar II disorders. Antidepressants should be used with caution in patients with bipolar disorder (particularly when used as monotherapy) because it carries a small but unpredictable risk of inducing mania and agitation (12).

Figure 3.2. Diagnostic algorithm for bipolar disorders. (Adapted with permission from Diagnosis and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed., text revision. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2002: Appendix A.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|