Major depressive disorder is characterized by a depressed mood most of the day nearly every day or a significant loss of interest or pleasure in almost all activities (anhedonia) for a period of 2 weeks or more. Various other specific depressive syndromes are characterized by both duration and number of mood symptoms.

Roughly 10% of patients in primary care settings meet the criteria for major depressive disorder.

Depression is common among postpartum women and patients with a personal or family history of depression, the experience of a recent trauma or loss, ongoing substance abuse, and comorbid systemic medical illnesses such as cancer, diabetes mellitus, neurologic disease, and cardiovascular disease.

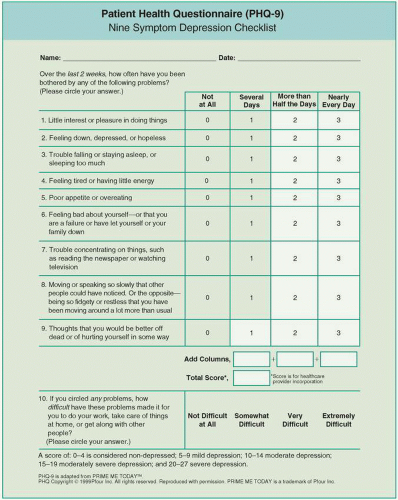

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that primary care practices should screen all adults for depression if the practice has systems in place to formally diagnose, treat, and follow patients with depression. The Physician Health Questionnaire, or PHQ-9, is a self-administered screening tool for depression that can be easily used in the primary care setting.

Most patients with depression respond well to psychotherapy, antidepressants, or a combination of both.

Sixty percent of those with major depressive disorder will have a second episode. Individuals who have had two to three major depressive episodes have an 80% to 90% chance of having yet another episode. Patients with recurrent depression should be educated about the early signs of depression and be on lifelong antidepressant therapy.

Suicide can occur at any phase of treatment for depression. More than half of all patients who die by suicide have visited their primary care provider within 1 month of their death.

More than 70% of men and 50% of women who die by suicide used a firearm. Physicians should ask depressed or anxious patients about suicidal ideation and access to firearms at each visit.

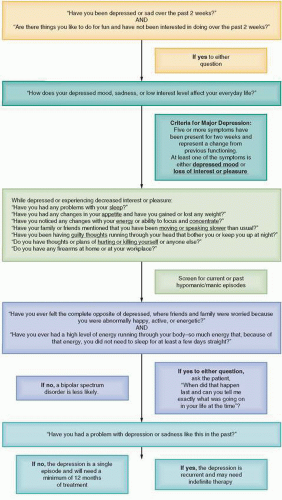

a mental health provider. Major depression is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR), as the presence of five or more depressive symptoms over a 2-week period (depressed mood or lack of interest in pleasurable activities must be present). The collective symptoms cause significant dysfunction and cannot be due to other illnesses such as anxiety, hypothyroidism, or alcohol- or substance-related disorders (1) (Table 2.1).

present and there is moderate impairment in functioning. Severe depression is suggested by the presence of many more symptoms than required for the diagnosis of major depression and related disabling functional impairment. Psychotic features such as hallucinations or delusions may be present in severe depression. Suicidal ideation may accompany mild, moderate, or severe depression.

Table 2.1 DSM-IV-TR Definition of Major Depression | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

with moderate to severe depression, and greater than 70 with severe depression. The BDI contains 21 items; scores of 0 to 9 represent minimal symptoms, 10 to 16 mild depression symptoms, 17 to 29 moderate symptoms, and 30 to 63 severe symptoms. Generally, the PHQ-9 is the easiest for the primary care provider to use.

Suicidal thoughts

Homicidal thoughts

Opportunities to reduce access to firearms and medications that may be harmful if taken in large quantities

Psychotic symptoms

Illicit drug or alcohol abuse

Systemic medical causes of depression (e.g., hypothyroidism)

Bipolar disorder with depressed or mixed episode

Table 2.2 Differential Diagnosis for Major Depressive Disorder | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree