Impaired Insight and the Therapeutic Relationship

The compulsive nature of addiction often remains latent or implicit in the clinic, despite becoming increasingly stimulus driven in naturalistic settings. This contrasts with how emotionally driven disorders such as anxiety and depression present in clinical settings. A depressed or anxious patient will frequently express strong emotions behaviourally as well as by self-reports and physiological arousal, whereas an addicted individual will often appear somewhat detached from the compulsive nature of the problem. Michael, for instance, a depressed 58-year-old man who came to see me recently, became distraught when reflecting back on the difficulties he had encountered due to his chronic anxiety, associated avoidance and alcohol dependence. His appraisals, ‘I’ve achieved nothing; I’ve wasted my life’, were entirely congruent with his sad mood and self-directed anger. The transparent manner with which Michael was able to report his thoughts made him a good candidate for traditional cognitive therapy, beginning with a reappraisal of his biased thinking. Similarly, Tim, a 47-year-old man with pervasive obsessive–compulsive tendencies involving mental rituals, told me that throughout the session he was struggling to focus on the interview as he felt compelled to count angles in the furniture in the room and engage in other neutralizing rituals. Again, this enabled a more accurate assessment of his problems by means of close observation and exploration of his compulsive thinking and obsessive behaviour ‘in the moment’. In both these cases the presenting problem is transported directly into the clinical arena and is thus available for examination and ultimately modification.

Addictive disorders present differently however. Both of these men also had chronic substance misuse problems with regard to alcohol and cocaine respectively. Despite attributing much of their lives’ difficulties to their inability to regulate their drug use, there was little, if any, cognitive, behavioural or motivational evidence of this in the consulting room: craving, urgency, preoccupation or suddenly leaving the clinic in order to procure drugs were notably absent. Further, close enquiry about recent drug use of often reveals little of the mindset or thought process of the client, although of course it reveals important information about environmental and contextual cues and triggers. Consider Suzy, a 35-year-old woman with a 15-year history of compulsive and excessive drinking together with recreational use of cocaine. She told me that, at six weeks of abstinence from both substances, she was doing ‘really well’ and had not experienced any urges or craving since being seen a week earlier. However, when next reviewed she told me that after she had consumed two or three drinks at a friend’s birthday party she accepted cocaine from another friend. The coping strategies rehearsed in advance for this planned encounter were not deployed. Suzy was not able to account for her lapse, although she was self-critical, accusing herself of lacking motivation. This scenario is, no doubt, a familiar one to therapists and their clients in the addiction arena. Here, I intend to examine problems in the therapeutic relationship from a dual-processing perspective.

Ambivalence is a systemic problem with a systemic solution

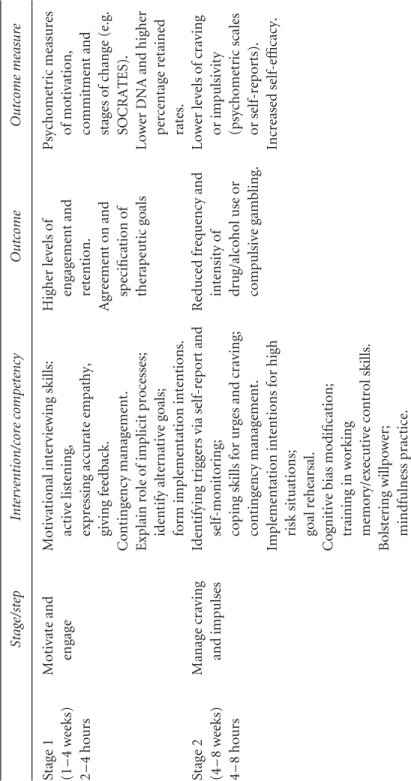

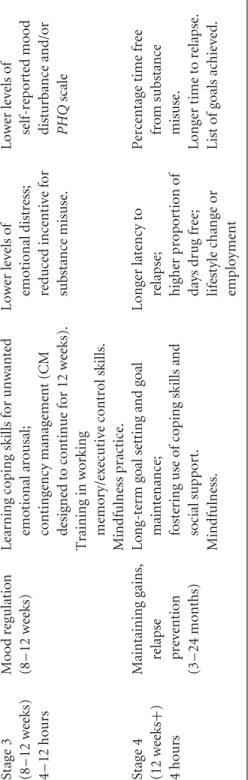

From a dual-processing perspective the ambivalence or motivational conflict that characterizes addictive behaviour is a clash of systems rather than an uneven balance sheet. The reflective system can enable lengthy deliberation about the merits and demerits of cocaine, for example, and sometimes the outcome is indeed a decision to give up. The impulsive system, however, does not have the flexibility to entertain conflicting tendencies, and hence enables the intrinsically more simple pursuit of satiation. Put simply, the impulsive system is not influenced by the outcome of weighing up the pros and cons of continuing or stopping a given behaviour. In the face-to-face encounter in the therapy room the impulsive system remains in the background, letting the reflective system do what it does best: thinking and talking. This can invalidate or distort the motivational enhancement process, as the source of impulsivity is not fully acknowledged or recognized. In due course the impulsive system will assert itself, for example when executive control is compromised by tiredness, stress or unexpected cue exposure. I shall outline how assessment and engagement strategies can be modified and applied to accommodate distorted decision making and impaired cognitive control. This scenario (see Table 6.1) depicts an altogether more difficult, but I would argue more realistic, route to addiction resolution than that implied by motivational augmentation via empathy, feedback and facilitated decision making.

Table 6.1 Outline of the CHANGE/Four-M Model.

Impaired insight

Traditional accounts of addiction emphasized the role of ‘denial’, the negation of problems associated with addiction by the affected individual. In the words of another client, ‘alcoholism is a disorder that tells you that do not have it’. Goldstein et al. (2009) considered lack of insight or self-awareness with regard to drug addiction as indications of altered or impaired functioning in corticolimbic regions associated with interoception, behavioural control, habit formation and evaluative learning as follows.

- The insula subserves interoceptive representation of somatic and emotional states, including craving. Interestingly, Naqvi et al. (2007) reported that a cohort of 19 smokers with brain damage involving the insula were 100 times more likely than a cohort of 50 smokers with brain damage not involving the insula to lose the urge to smoke and subsequently give up smoking.

- The anterior cingulate cortex, involved in behaviour regulation and error monitoring. It will be recalled that there is evidence that chronic misusers of cocaine, heroin, alcohol, cannabis and other drugs evidence underactivity in this key component of cognitive control (Garavan and Stout, 2005). Carter and van Veen (2007) have proposed that the role of the ACC is to detect conflict between concurrently active, competing representations and to engage the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) to resolve this. This leads to top-down or executive control being leveraged to improve performance. Compromised ACC and DLPFC functioning, as observed in chronic drug users, therefore compromises cognitive control.

- The dorsal striatum is a key conduit for dopaminergic transmission triggered by drug use. Everitt et al. (2008) proposed, albeit based largely on evidence from nonhuman-animal studies, that the transition from controlled to compulsive drug seeking represents a switch at the neural level from prefrontal cortical to dorsal striatal control over addictive behaviours. Applied to humans, this implies that the more compulsive drug seeking becomes, the more remote it is from the cortical areas that might support insight and decision making. However, as pointed out by Stacy and Wiers (2010), habit theories may be more applicable to subsets of drugs such as nicotine due to the high frequency of cigarette smoking. This has obvious implications for psychotherapeutic approaches such as motivational interviewing (MI), or indeed cognitive therapy, that rely on elicitation of beliefs and motives in order to facilitate decision making.

By definition, it is not possible to have insight regarding stimuli of which one is unaware. The Childress et al. (2008) study referred to in Chapter 1 is relevant here. The very early detection (33 ms) of drug-relevant cues, as evidenced by activation in areas such as the amygdala observed in abstinent cocaine users, means that pre-emptive conscious control is impossible. Mobilizing the necessary inhibitory or diversionary processes can take several hundred milliseconds. This enables speculation that stimuli that are not consciously detected can be, if anything, more influential than those that can be appraised consciously. There appears to be converging evidence from psychophysiology research, cognitive processing studies and neuroimaging findings with individuals addicted to alcohol, tobacco and cocaine that stimuli that evade conscious detection are nonetheless differentiated preconsciously. However, this lack of awareness of stimuli does not necessarily prevent these same stimuli from capturing attention and triggering purposeful (here, drug-seeking) behaviour.

The Sad Case of Julia

This lack of insight can have profoundly negative consequences. A year ago, I saw Julia, a 39-year-old woman, in my clinic. She told me that, over a period of several years, her three children had been placed in care because of her history of crack cocaine addiction. She described how she had left rehab and remained drug free for over a year before becoming pregnant. With less than three months of her term remaining she met a supplier of crack cocaine who lived nearby. Within a week she was using daily, despite being closely monitored by health- and social-care professionals: she knew the consequences. Julia did not recall experiencing any particular craving or urge initially but she continued to use until she was due to give birth. Prior to this, the crack dealer had pleaded with her to stop, probably as she was distressing his other customers. Inevitably, she was not given the opportunity to care for her newborn and apparently healthy baby, who was placed in care from birth. She returned home alone. What was striking about this sad episode was that Julia subscribed to the view any observer would: this was a personal tragedy for her, and the children she had witnessed being removed from her care one by one. Yet she had proved powerless to defer the gratification offered by her drug of choice pending the longer-term and infinitely more gratifying rewards of parenthood. Note also that Julia had by all accounts been drug free for over 18 months prior to her relapse. What cognitive or motivational processes could account for this? Julia was an articulate lady but introspection did not yield any particular insights. She appeared to sleepwalk into this avoidable catastrophe. Any input I could provide was too little, too late. In any event, I encouraged Julia to view her behaviour when confronted with the possibility of getting cocaine as being, albeit momentarily, governed by an impulsive system over which she had neither control nor insight when it really mattered. Sadly, any consideration of this did not enable her to undo the consequences of her relapse but recognition of the involuntary processes involved helped reduce her tendency towards self-blame and depression. This vignette starkly illustrates the challenge facing those aiming to recover from addiction. In the following paragraphs I shall attempt to develop some insight into the cognitive processes that might have had a bearing on Julia’s behaviour.

Conflicted Motivation is the Key

Historically, motivational approaches were a reaction to the confrontational stance advocated by traditional approaches such as Twelve-Step in an effort to break down ‘denial’. In the case of Julia, this would entail orchestrating a situation where she would admit that she was addicted and powerless in the face of temptation. By confronting ambivalence rather than putative denial, MI provided a more nuanced and engaging approach. MI is thus appropriately aimed at leveraging people into treatment programmes, or encouraging them to simply attend for the next session. The mechanisms and utility of MI approaches are, however, neither fully clear nor fully established as drivers of change. To be sure, a nascent decision to give up is sometimes translated into long-term change, but more often the resolution is not implemented or fails to endure (see Burke et al., 2003). Moreover, the mechanisms of this implementation process are unclear because it is difficult to establish a causal link between a therapeutic mechanism such as evoking commitment to change and clinical outcomes. Miller and Rose (2009) nonetheless considered a range of possible therapeutic mechanisms, such as therapist attributes including empathy, client behaviour such as ‘change talk’, or evocation of faith or hope. Linguistic analysis (Amrhein et al., 2003) of how people negotiate and decide to change suggested their utterances could be differentiated according to the following motivational components: desire, ability, reasons, readiness, need and commitment. The extant motivational model assumes that, given the right coaching, the essentially rational person who happens to be addicted will make a decision that is in his or her own best interests. In many cases, this would work: most people are open to persuasion in the face of a well-presented case for change or flexibility. But addiction can be an exception, as demonstrated by the sad case of Julia. Whether reflecting denial, negation or simply selfishness, her behaviour seems difficult to understand. Unless, that is, Julia was herself unable to fathom her own motives. As briefly reviewed above, neuroscientific findings do indicate a lack of interoceptive awareness in addiction. This suggests that one person’s ascription of denial (the observer) is another’s lack of insight (the addicted one).

Goal Setting and Maintenance

Because the MI dialogue takes place mainly in the reflective or declarative mode, it is assumed that the addicted individual will be able to authentically chart their motivational status. It is hoped, for instance, that by listing positive and negative attributes of drug-using behaviour individuals will re-evaluate their choices and resolve to change. Clearly, working with clients to explore the positives and negatives of their addictive lifestyle is likely to be useful, especially if done in the empathic and nonjudgemental manner that characterizes the spirit of MI. This evaluative process can of course facilitate decision making and goal setting, priorities at the engagement stage of therapy. When risks to health, relationships and livelihood are juxtaposed with the transient rewards of the addictive pursuit, the balance sheet often appears rather heavily weighted towards giving up. For example, a parent could acknowledge the pleasurable effects of cocaine while at the same time recognizing that this has a negative effect on her ability to care for her young child. The discrepancy between self-gratification and the valued role of being a good parent evoked by this process creates tension that the motivational therapist can exploit by steering the client towards making a decision apropos her drug use. This could entail simply agreeing to come back for another motivational encounter, an undertaking to avoid using in certain situations or perhaps making a commitment to give up. In cognitive-processing terms this goal definition and goal maintenance are key to cognitive control.

The Importance of Between-Session Change

It seems reasonable to conclude that MI can facilitate decision making and increase commitment to change within the session. Here, the reflective mode is fully engaged, the client dutifully swayed by the force of logic. Ultimately, this approach, termed ‘cognitive algebra’ (Stacy and Wiers, 2010), fails to account for the characteristic tendency of habitual behaviour to proceed by default at critical decision points or when significant cues are available, especially between sessions. These cues only need to capture attention momentarily in order to initiate action (see Norman and Shallice, 1986, and Chapter 4). MI thus assumes greater insight into the motivational drivers of addiction than is likely or even possible. This reduces the therapist’s ability to empathize accurately with the clients that they are ardently trying to motivate. MI also assumes a more rational decision-making process than is likely to be the case, thereby assigning more credence to undertakings of restraint proffered by the client. In effect, this is an example of a ‘planning fallacy’ (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974; Kahneman, 2003) and sets the scene for failure. Consequently, the therapeutic alliance can be undermined in some of the ways explored below. MI nonetheless remains a valid and flexible approach that can accommodate the emerging findings and new perspectives outlined here. The emphasis on empathy, decision making and goal setting is fully justified at the beginning of a therapeutic journey aimed at overcoming impulsive behaviour.

Neurocognitive Perspectives on Motivation

In the CHANGE model engagement is, predictably, the first phase (see Table 6.1) and aims to help the client to form attainable goals. The related tasks of goal setting and goal maintenance are seen as core components of self-regulation or cognitive control. As discussed in Chapter 3, goals encoded in WM are crucial to organizing behaviour and can exert top-down influence on selective attention: goal setting is thus seen a means of exerting cognitive control. In the later sections of this chapter I shall address formulation, again drawing on a model that accommodates the operation of implicit cognitive and behavioural processes. This includes an exploration of how therapists conceptualize addiction and the possibility of implicit biases influencing formulation. A particular focus is on nurturing the therapeutic alliance in the context of a behaviour that occurs impulsively, with little warning and often little insight into its precursors. In turn, this sets the scene for Chapters 7 and 8 (managing impulses and mood) that describe addressing impaired cognitive control in the context of addiction and coexisting problems, somewhat arbitrarily signified by ‘M’ for managing impulses and ‘M’ for mood. To this end, some examples and strategies are provided.

Motivational Interviewing in Practice

FRAMES

As we saw at the beginning of this chapter, the conceptual basis of MI can be challenged as it assumes a rather more rational decision-making process in the face of impulsivity than is in fact the case. It nonetheless has enabled the development of a useful framework for engaging and preparing people for therapeutic intervention.

FRAMES is an acronym that captures the key ingredients for building motivation and commitment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree