Chapter 10 The second edition of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders published in 2005 included a separate section devoted to sleep-related movement disorders. This category includes restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movements in sleep and periodic limb movement disorder, sleep-related leg cramps, sleep-related bruxism, sleep-related rhythmical movement disorders, and other sleep-related movement disorders caused by a known physiological condition or substance abuse and those not caused by a substance or known physiological condition (e.g., other psychiatric or behavioral sleep-related movement disorders). Most of the nosological entities characterized by prominent motor abnormalities are, however, included in the category of parasomnias (e.g., undesirable motor events and behavior occurring during sleep that do not necessarily disturb sleep architecture and that are not caused by abnormalities intrinsic to basic sleep mechanisms). Parasomnias include disorders of arousals (e.g., confusional arousals, sleepwalking, sleep terrors arising out of non–rapid eye movement [NREM] sleep), those associated with rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (e.g., REM sleep behavior disorder, parasomnia overlap disorder, status dissociatus, nightmares, and recurrent isolated sleep paralysis), and other parasomnias (e.g., nocturnal dissociative disorder, catathrenia or nocturnal groaning, exploding head syndrome, and sleep-related eating disorders). While we await a deeper understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms, however, description remains the first step in the knowledge of a phenomenon. Video recordings and polygraphic pictures go a long way in helping clinicians to recognize and characterize the various movement abnormalities encountered in the everyday practice of sleep medicine. Therefore an atlas showing characteristic polysomnographic (PSG) features of different motor disorders arising during sleep provides a good guide in the interpretation of the tracings and helps technicians and physicians recognize patterns useful in the differential diagnosis. Figures 10.1 to 10.12 provide examples of PSG tracings and a brief clinical description for clinical-physiological correlation derived from the following motor disorders emerging during sleep: sleep terror (see Fig. 10.1), status dissociatus (see Fig. 10.2), propriospinal myoclonus at sleep onset (see Fig. 10.3), faciomandibular myoclonus (see Fig. 10.4), sleep-related eating disorder (see Fig. 10.5), bruxism (see Fig. 10.6), bruxism with catathrenia (see Fig. 10.7), hypnagogic foot tremor (see Fig. 10.8), alternating leg muscle activation (see Fig. 10.9), excessive fragmentary myoclonus (see Fig. 10.10), and confusional arousal (see Figs. 10.11 and 10 12). FIGURE 10.1 Sleep terror. FIGURE 10.2 Status dissociatus.

Motor Disorders During Sleep

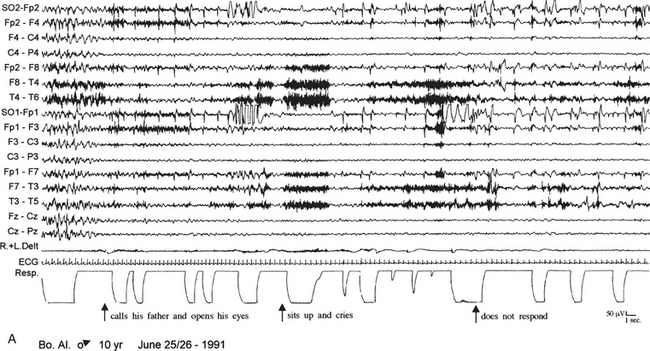

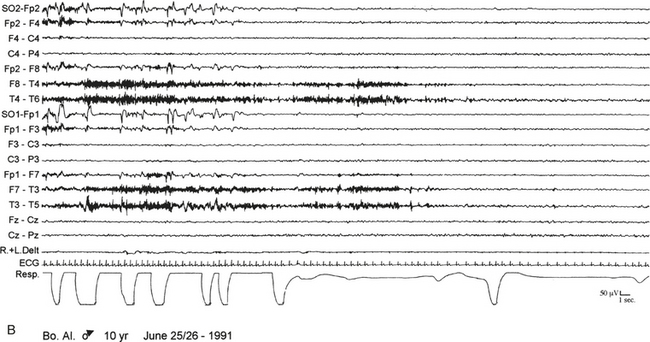

A 10-year-old boy presented with a 6-year history of sudden awakenings usually within 2 hours after sleep onset. A, During the episodes the patient sat up with a fearful expression and glassy eyes, vocalized and screamed with tachycardia, tachypnea, flushing of the skin, and mydriasis. The patient was confused and disoriented if awakened. The polysomnographic recording shows that the episode arises from stage N3 of sleep with a diffuse “hypersynchronous” rhythmical delta activity, deep inspiration, and tachycardia. At the beginning of the episode the patient calls his father, open his eyes, and cries, but electroencephalographic background activity remains slow. B, At the end of the episode the patient goes back to sleep. ECG, Electrocardiogram; top 16 channels, electroencephalogram (international nomenclature system); SO, supraorbital electrode; R.+L. Delt., right and left deltoideus muscle; Resp., thoracoabdominal respiration.

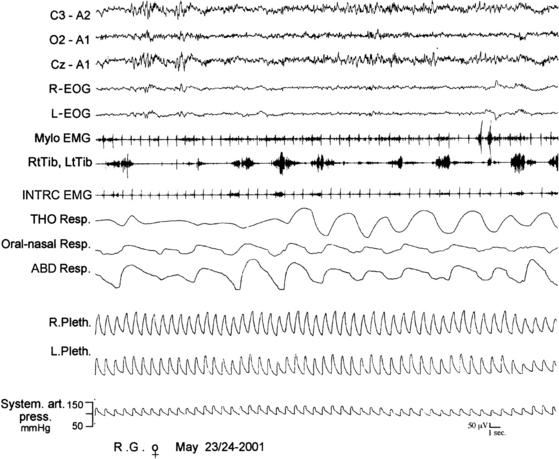

A 66-year-old woman with harlequin syndrome suffered, approximately 1 year after right jaw and multiple limb trauma, restless sleep, interrupted by excessive motor and sometimes harmful activities associated with vocalization and a report of dreaming corresponding to the motor manifestations. Hypnagogic hallucinations and sleep paralysis rarely occurred. Polysomnographic tracing shows intermingled non–rapid eye movement (NREM) and rapid eye movement (REM) electroencephalographic features (top three channels). In particular, sleep spindles were observed during REM sleep patterns (sawtooth waves, desynchronized high-frequency/low-amplitude activity, and REMs). Mylohyoid (Mylo EMG) muscle atonia was not complete with brief, sudden twitches and tonic electromyographic bursts. Respiration shows irregular tracings of REM sleep. R-EOG, Right electro-oculogram; L-EOG, left electro-oculogram; Mylo, mylohyoideus; RtTib, right tibialis anterior; INTRC, intercostalis; THO Resp, thoracic respiration; ABD Resp, abdominal respiration; R.Pleth, right plethysmogram; L.Pleth, left plethysmogram; System. art. press., systemic arterial pressure.

Motor Disorders During Sleep

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree