CHAPTER 12

Movement Disorders

I. Definition

A. Motor disorders are defined as a group of neurological disorders characterized by paucity of movement (hypokinesia), excessive movement (hyperkinesia), or sometimes a combination of both.

B. Speed, amplitude, and quality of movement are affected in these disorders.

C. Classification

HYPOKINETIC MOVEMENTS | HYPERKINETIC MOVEMENTS |

Parkinsonism Hypothyroid slowness Stiff muscles Catatonia Psychomotor depression Cataplexy and drop attacks | Tremors (an oscillatory, usually rhythmic and regular movement affecting one or more body parts) Dystonia (sustained or intermittent muscular contractions resulting in repetitive abnormal movements and/or postures) Chorea (involuntary, irregular, purposeless, nonrhythmic, abrupt, rapid, unsustained movements that seem to flow from one body part to another) Ballism (large-amplitude choreic movements of the proximal parts of the limbs, causing flinging and flailing of limbs) Athetosis (slow, writhing, continuous, involuntary movement) Myoclonus (sudden, brief, shock-like involuntary movements caused by muscular contractions or inhibitions [negative myoclonus]) Ataxia (incoordination characterized by jerky movement or posture) Restless legs (unpleasant crawling sensation of the legs, particularly when sitting and relaxing in the evening, which then disappears on walking) Tics (consist of abnormal movements or sounds; can be simple or complex) Stereotypy (coordinated movement that repeats continually and identically) Hemifacial spasm (unilateral facial muscle contractions) Hyperekplexia (excessive startle reaction to a sudden, unexpected stimulus) Akathisia (feeling of inner, general restlessness, which is reduced or relieved by walking about) Myokymia (fine persistent quivering or rippling of muscles) Myorhythmia (slow-frequency, prolonged, rhythmic or repetitive movement without the sharp wave appearance of a myoclonic jerk) Paroxysmal dyskinesias (recurrent episodes of chorea, dystonia, athetosis, ballism, or a combination of these movements with normal neurologic examination in between the episodes) |

II. Parkinsonism: Core features: resting tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia akinesia, loss of postural reflexes (TRAP)

A. Etiologies

Idiopathic parkinsonism Parkinson-plus syndromes | Parkinson’s disease (PD) Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) Multiple-system atrophy (MSA) Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) Corticobasal degeneration (CBD) Frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism (FTD-P) |

Secondary parkinsonism | Drug induced (antiemetics, neuroleptics, reserpine, tetrabenazine, lithium, flunarizine, cinnarizine, diltiazem) Vascular Structural (hydrocephalus, especially normal-pressure hydrocephalus; trauma; tumor) Hypoxia Toxins (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine [MPTP], CO, manganese, cyanide, methanol) Infections (fungal, AIDS, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, postencephalitic parkinsonism, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease) Metabolic (hypo-/hypercalcemia, chronic hepatocerebral degeneration, Wilson’s disease) Paraneoplastic parkinsonism Psychogenic |

Heredodegenerative disease | Alzheimer’s disease (AD) Huntington’s disease Machado-Joseph disease Hallervorden-Spatz disease X-linked dystonia-parkinsonism (Lubag) |

B. PD: neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the gradual and progressive onset of parkinsonism in the absence of known causes

1. Clinical diagnosis: unilateral onset with asymmetry of clinical signs; bradykinesia, which is the most important clinical sign for the diagnosis of parkinsonism; rest tremor (in 80%, usually low frequency [4–7 Hz] with classic pronation-supination and pill-rolling pattern); rigidity of a lead pipe quality and in later stages of the disease postural instability; insidious, often unilateral onset of subtle motor features; rate of progression varies; eventually symptoms worsen and become bilateral; with absence of other neurologic signs (spasticity, Babinski signs, atypical speech); absence of lab or radiologic abnormalities (e.g., strokes, tumors); slowly progressive with significant and sustained response to dopaminergic therapy; classically or traditionally defined by motor features, it is now known to be associated with a host of nonmotor symptomatology, including autonomic dysfunction (constipation, impotence, seborrheic dermatitis, bladder dyssynergia); neuropsychiatric dysfunction (NB: depression in up to 50%, dementia in up to 20%; anxiety, panic attacks, hallucinations, delusions); nearly all PD patients suffer from sleep disorders (e.g., insomnia, sleep fragmentation, excessive daytime sleepiness, nightmares, REM behavior disorder); treatment must be individualized and continually adjusted as the disease evolves. Nonmotor symptoms are now known to cause more impairment in quality of life and cause more caregiver stress than motor features.

2. Epidemiology of PD: estimated prevalence: 500,000 to 1 million patients in United States; incidence: 40,000 to 60,000 new cases per year; average age of onset is 60 years; affects up to 0.3% of general population, but 1% to 3% of those over 65 years old (y/o); PD is largely a disease of older adults: only 5% to 10% of patients have symptoms before 40 y/o (young-onset PD).

3. Genetic factors: autosomal dominant (AD) and recessive patterns of inheritance have been identified.

a. Park 1/Park 4: chromosome 4q21-23; alanine-53-threonine mutation in the α synuclein gene; AD; earlier disease onset (mean age 45 years), faster progression, some with fluent aphasia; central hypoventilation

b. Park 2: chromosome 6q25.2-27; the parkin gene; parkin; autosomal recessive (AR); relatively young-onset parkinsonism; dystonia at onset; symmetric involvement; good levodopa response; slow disease progression; absence of Lewy bodies at autopsy

c. Park 3: chromosome 2p13; AD but with 40% penetrance; all from northern Germany and southern Denmark; nigral degeneration and Lewy bodies at autopsy; dementia may be more common.

d. Park 5: mutation in ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 on chromosome 4p14; AD; late-onset progressive parkinsonism

e. Park 6: mutation of the PINK1 gene on chromosome 1p35-36; AR; early-onset parkinsonism; phenotype similar to Parkin-PD but with cognitive and psychiatric features; slow progression, and marked response to levodopa

f. Park 7: mutation of DJ-1 gene on chromosome 1p36; early-onset AR parkinsonism, slow progression, with levodopa responsiveness; mostly from the Netherlands

g. Park 8: mutation of the LRRK2 gene on chromosome 12q12; AD; age of onset in the 60s with variable alpha synuclein and tau pathology

h. Park 9: aka Kufor-Rakeb syndrome; mutation of ATP13A2 on chromosome 1q36; AR; age of onset in the 30s; vertical gaze palsy, pyramidal signs, facial and finger mini-myoclonus, cognitive impairment

i. Park 10 and 11: reported but inheritance is still unclear, probably AD, and gene mutation has not yet been identified.

j. Park 14: mutation of PLA2G6 on chromosome 22q13. AR; parkinsonism associated with dystonia

4. Pathology: many theories on cell death, but no firm conclusions; apoptosis, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, excitotoxicity, deficient neurotrophic support, immune mechanisms; loss of pigmentation of the substantia nigra and locus ceruleus with decreased neuromelanin-containing neurons; affected neurons contain large homogenous eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions called Lewy bodies, which possess neurofilament, ubiquitin, and crystalline immunoreactivity.

5. Pharmacotherapy of PD

a. Amantadine: N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist useful for newly diagnosed patients with mild symptoms and in some patients with advanced disease; provides mild to moderate benefit by decreasing tremor, rigidity, and akinesia; rarely effective as monotherapy for more than 1 to 2 years, may be continued as adjunctive agent; effective for levodopa-induced dyskinesias; adverse effects: anticholinergic effects, livedo reticularis, renal disease increases susceptibility to adverse effects, leg edema, neuropsychiatric effects—confusion, hallucinations, nightmares, insomnia

b. Anticholinergic agents: option for young patients (<60 y/o) whose predominant symptoms are resting tremor and hypersalivation (sialorrhea); available agents—trihexyphenidyl and benztropine; adverse effects often limit use—memory impairment, confusion, hallucinations

c. Levodopa: advantages—most efficacious antiparkinsonian drug to date, immediate therapeutic benefits (within 1 week), easily titrated, reduces mortality, lower cost; disadvantages—no effect on disease course, no effect on nondopaminergic symptoms (such as dysautonomia, cognitive disturbances; little or no effect on axial symptoms such as sialorrhea, dysphagia, hypophonia and postural instability), motor fluctuations and dyskinesia develop over time (especially in younger patients, those with more severe disease and those requiring higher doses); acute adverse effects—nausea/vomiting (dopamine decarboxylase inhibitor [carbidopa or benserazide] alleviates by inhibiting amino acid decarboxylase enzyme), confusion, psychosis, dizziness; chronic effects—hallucinations; motor fluctuations—peak dose or diphasic dyskinesias, wearing off (predictable or sudden off), delayed on, yo-yoing; now available in different formulations: short-acting, long-acting, orally dissolving (Parcopa), extended release (Rytary), and in liquid gel form delivered directly to the duodenum through an external pump (Duopa or Duodopa).

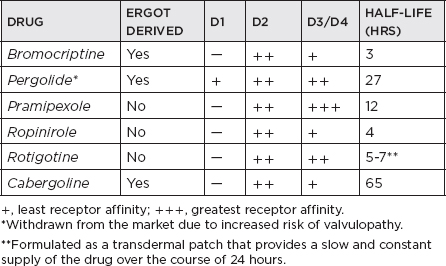

d. Dopamine agonists

i. Effective for initial monotherapy; also indicated in combination with levodopa to smoothen clinical response in advanced disease; directly stimulate postsynaptic dopamine receptors; effective against key motor symptoms (tremor, bradykinesia, and rigidity); early use shows reduced risk of dyskinesia compared with levodopa therapy, although antiparkinsonian effects consistently inferior to levodopa; adverse effects: slightly higher than levodopa—nausea/vomiting, sedation, orthostatic hypotension, hallucinations, dyskinesia in more advanced disease, leg edema, NB: daytime somnolence including sleep attacks; ergot-derived side effects—livedo reticularis, erythromelalgia, cardiac, pulmonary or retroperitoneal fibrosis, valvulopathy; potential to cause impulse control disorders (ICDs), which include pathologic gambling, hypersexuality, compulsive eating.

ii. Apomorphine: available in the United States as an injectable (subcutaneous) short-acting dopamine agonist; approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a “rescue therapy” for symptoms of wearing off in advanced PD patients; benefits take effect as early as 5 minutes from the time of injection, but lasts for only 1 to 1.5 hours.

iii. Rotigotine: the latest dopamine agonist approved in the United States for monotherapy in early PD and as an adjunct treatment for levodopa in advanced PD; available in transdermal (patch) form; side effects, other than skin reactions, are similar to non-ergot dopamine agonists, including somnolence, sleep attacks, nausea, vomiting, weight gain, hallucinations, and so forth.

iv. Impulse control disorders (e.g., hypersexuality, binge eating, pathological gambling, and compulsive shopping) have been associated with PD medications, especially dopamine agonists. Dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome (DAWS) has been described to occur in patients when dopamine agonists are withdrawn because of side effects, characterized by agitation, depression, anxiety, and other symptoms similar to that seen with psychostimulant withdrawal.

e. NB: Catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitors: inhibit levodopa catabolism to 3-O-methyldopa, increasing levodopa bioavailability and transport to brain; extend duration of levodopa effect; indicated for treatment of patients with PD experiencing end-of-dose wearing off with levodopa; no role as monotherapy; used only in combination with levodopa; two available agents: entacapone (Comtan®) and tolcapone (Tasmar®); fatal fulminant hepatitis in four tolcapone-treated patients: requires liver function monitoring and signed patient consent; side effects: dyskinesias, diarrhea (4%–10%), nausea

f. Monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors

i. Selegiline: selective monoamine oxidase-B inhibitor with doses less than 10 mg/day; Deprenyl and Tocopherol Antioxidative Therapy of Parkinsonism (DATATOP) study showed unlikely neuroprotective effect and mild symptomatic benefit in early PD; with higher doses, avoid tyramine-rich food, meperidine, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, as monoamine oxidase-B selectivity is lost, predisposing to cheese effect

ii. Rasagiline: new selective, once-per-day MAO-B inhibitor; FDA approved for monotherapy in early PD, and also for adjunctive treatment to levodopa in moderate to advanced PD; “off time” was decreased by 0.9 hours among PD patients with wearing-off symptoms compared to placebo in the PRESTO trial and LARGO trials; the recently concluded ADAGIO trial showed that early, medication-naïve PD patients placed on rasagiline at 1 mg per day immediately at study entry had a better average total Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) score after 3 years compared to those who received rasagiline 9 months later; unlike selegiline, this new MAO-B inhibitor is not broken down into amphetamine metabolites; however, dietary precaution on tyramine-rich foods is advised.

g. Management of hallucinations (psychosis) in PD and PD dementia: eliminate medical causes of delirium (e.g., infection or dehydration); discontinue nonparkinsonian psychotropic medications, if possible; eliminate antiparkinsonian drugs in order of their potential to produce delirium (anticholinergics > amantadine > monoamine oxidase-B inhibitors > dopamine agonists > catechol methyltransferase inhibitor > levodopa); use regular levodopa formulation at lowest possible dose; use atypical antipsychotic agents (clozapine > quetiapine > other atypicals). NB: Quetiapine is preferred despite clozapine being the gold standard; risk of agranulocytosis with clozapine necessitates regular white blood cell (WBC) monitoring.

Rivastigmine: for cognitive impairment, the first FDA-approved medication for Parkinson’s disease with dementia (PDD); available orally and in patch form; may also improve mild hallucinations; most frequent side effects: nausea, vomiting, and tremors (usually mild and transient but can be bothersome to some); no worsening in the UPDRS motor scores in patients who were randomized to rivastigmine compared to placebo in the EXPRESS trial

h. Surgical management of PD: lesion versus deep-brain stimulation; lesion (thalamotomy—most effective for parkinsonian and essential tremor; pallidotomy—improves bradykinesia, tremor, rigidity, dyskinesia in PD) has the advantage of simplicity, no technology or adjustments required, no indwelling device; however, disadvantages include inability to do bilateral lesions without increased risk of dementia, swallowing dysfunction, and so forth, and side effects could be permanent; deep-brain stimulation surgery of globus pallidus internus or subthalamic nucleus may improve most symptoms of PD and has the advantage of minimal to no cell destruction and the ability to perform deep-brain stimulation on both sides and to adjust the stimulation settings as the disease progresses; however, deep-brain stimulation is more expensive, requires technical expertise, and could be prone to hardware malfunctions (e.g., kinks, lead fractures) or infections; the ideal surgical candidate: clear PD diagnosis with unequivocal and sustained levodopa response, relatively young, nondemented, nondepressed, nonanxious, emotionally and physically stable.

C. Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is a neurodegenerative condition characterized by parkinsonism, autonomic dysfunction, and cerebellar dysfunction in variable combination; the term encompasses three overlapping entities: (1) MSA with orthostatic hypotension, previously known as Shy-Drager syndrome; (2) MSA parkinsonism subtype (MSA-P), previously known as striatonigral degeneration; and (3) MSA cerebellar subtype (MSA-C), previously known as olivopontocerebellar atrophy.

1. Clinical manifestations

a. MSA-P: a sporadic disorder with an insidious onset of neurologic symptoms in the 4th to 7th decades of life; the mean age at onset is 56.6 years, and there is no sex preference; akinetic rigid syndrome, similar to PD; patients initially present with rigidity, hypokinesia, and sometimes unexplained falling; may be symmetric or asymmetric at onset; the course is relentlessly progressive, with a duration ranging from 2 to 10 years (mean, 4.5–6.0 years); eventually, patients are severely disabled by marked akinesia, rigidity, dysphonia or dysarthria, postural instability, and autonomic dysfunction; mild cognitive and affective changes with difficulties in executive functions, axial dystonia with anterocollis, stimulus-sensitive myoclonus, and pyramidal signs; respiratory stridor due to moderate to severe laryngeal abductor paralysis can sometimes occur; resting tremor is not common; cerebellar signs are typically absent; the majority do not respond to levodopa, except early in the course.

b. MSA-C: essentially a progressive degenerative cerebellar-plus syndrome; male-to-female ratio is 1.8:1.0 in familial olivopontocerebellar atrophy and 1:1 in sporadic olivopontocerebellar atrophy; the average age of onset is 28 years for familial and 50 years for sporadic olivopontocerebellar atrophy; the mean duration of the disease is 16 years in familial and 6 years in sporadic olivopontocerebellar atrophy; cerebellar ataxia, especially involving gait, is the presenting symptom in 73% of patients; dysmetria, limb ataxia, and cerebellar dysarthria are characteristic; other initial symptoms include rigidity, hypokinesia, fatigue, disequilibrium, involuntary movements, visual changes, spasticity, and mental deterioration; as the disease progresses, cerebellar disturbances remain the most outstanding clinical features; dementia is the next most common symptom in familial olivopontocerebellar atrophy and is present in 60% of patients; dementia occurs in 35% of sporadic olivopontocerebellar atrophy patients.

2. Pathology: MSA is characterized pathologically by cell loss and gliosis in the striatum and substantia nigra; macroscopically, the putamen is most affected, with significant atrophy; the substantia nigra exhibits hypopigmentation; microscopically, severe neuronal loss, gliosis, and loss of myelinated fibers are evident in the putamen, less on the caudate; gliosis is found, but Lewy bodies or neurofibrillary tangles are not commonly present; a recent finding in cases of multiple system atrophy is the presence of argyrophilic cytoplasmic inclusions in oligodendrocytes and neurons; the inclusions are composed of granule-associated filaments that have immunoreactivity with tubulin, τ protein, and ubiquitin; they seem to be specific for MSA; there is considerable clinical and pathologic overlap among the three MSA syndromes; in MSA-C, neuronal loss with gross atrophy is concentrated in the pons, medullary olives, and cerebellum; in MSA with orthostatic hypotension, the intermediolateral cell columns of the spinal cord are affected as well.

3. Differential diagnosis: MSA is most frequently misdiagnosed as PD; features suggestive of MSA include unexplained falls early in disease, early appearance of autonomic symptoms, rapid progression of parkinsonian disability, lack of or unsustained significant response to levodopa therapy, symmetric presentation, and minimal or no resting tremors; PD is different from MSA-C because of the absence of prominent cerebellar symptoms and from MSA syndrome because of a lack of pronounced orthostatic hypotension; MSA’s relatively symmetric presentation will not be confused with cortical-basal ganglionic degeneration, and its intact oculomotor function distinguishes it from progressive supranuclear palsy; mentation is relatively preserved in MSA-P (less so in MSA-C) and is helpful in differentiating from dementing diseases, such as AD with parkinsonian features, diffuse Lewy body disease, or Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease; finally, MSA should be distinguished from acquired parkinsonism by ruling out infectious, toxic, drug-induced, vascular, traumatic, and metabolic causes.