Adults

Pediatric (<18 years)

TIA

55 %

TIA

38 %

Stroke

59 %

Stroke

40 %

Hemorrhage

16 %

Hemorrhage

6 %

Seizure

14 %

Seizure

11 %

Headache

49 %

Headache

22 %

Figure 10.1

Ethnicity of the 703 moyamoya patients (1,132 revascularization procedures) treated at Stanford 1990–Feb 1, 2013

Table 10.2

Disorders associated with moyamoya at Stanford

Disorder | Number of patients |

|---|---|

Down syndrome | 23 |

Neurofibromatosis | 18 |

Graves’ disease (hyperthyroid) | 11 |

Sickle cell disease | 6 |

Primordial dwarfism | 6 |

Coarctation of the aorta | 5 |

Post-radiation | 5 |

Thalassemia | 4 |

Morning Glory syndrome | 2 |

Optic glioma | 2 |

Alagille syndrome | 1 |

G6PD deficiency | 1 |

Glycogen storage disease | 1 |

Hurler’s disease | 1 |

Lysosomal storage disease | 1 |

MELAS syndrome | 1 |

Noonan syndrome | 1 |

Russell Silver syndrome | 1 |

Systemic autoimmune disease | 1 |

Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome | 1 |

Figure 10.2

Gender of the 703 moyamoya patients (1,132 revascularization procedures) treated at Stanford 1990–Feb 1, 2013

Natural History

The natural history of moyamoya is not completely understood, although there is inevitable progression in the majority of patients. The rate of progression, however, is unpredictable. Two-thirds of patient have symptomatic progression over 5 years and the outcome is poor without treatment [6, 19, 20]. Those with unilateral presentation often develop moyamoya on the other side [14] and medical therapy alone is not effective in preventing progression. The 5-year stroke rate is 20–65 % with medical treatment only [5, 10, 28]. “Asymptomatic” moyamoya may not be entirely accurate [18], as 20 % of patients have silent infarcts (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]-positive) and a 3.2 %/year stroke risk.

Diagnosis

Moyamoya diagnosis involves taking careful histories and evaluating several radiology studies. Patients are asked in-depth questions about the onset, frequency, location, duration and severity of any neurological symptoms in order to determine if they are related to moyamoya and which side of the brain might be affected. Moyamoya can initially be confused with other neurological disorders, such as multiple sclerosis [7], until radiological studies confirm findings consistent with narrowing or closure of brain arteries.

MRI scans reveal brain structures and identify locations of infarcts or areas of bleeding (Fig. 10.3), MRI or computed tomography (CT) angiograms noninvasively screen blood vessels of the brain (Figs. 10.4 and 10.5) and cerebral angiograms show the structure of brain arteries (Fig. 10.6). Most common findings include narrowing or closure of the ICA or its branches. In addition, compensatory thin-walled arteries that develop over time may be present. These fragile “moyamoya” vessels, which led Japanese doctors to initially describe the “puff of smoke” appearance on angiograms [29], can bleed. If treatment is indicated, external carotid (scalp) arteries are examined to choose the best donor artery and the optimal technique for surgery.

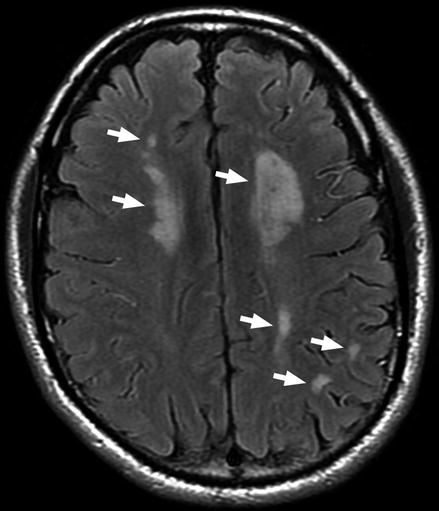

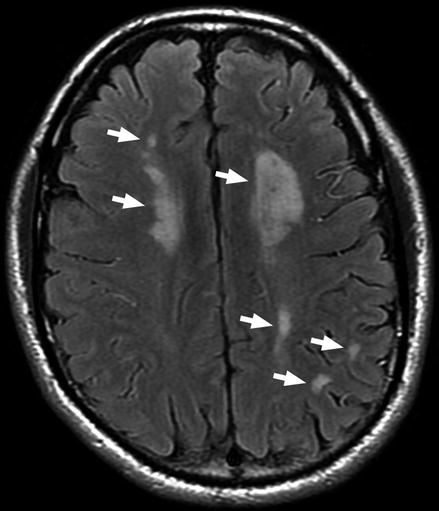

Figure 10.3

Preoperative MRI head scan showing strokes (arrows) on both sides of the brain secondary to moyamoya

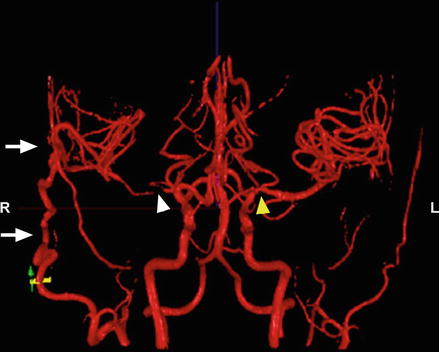

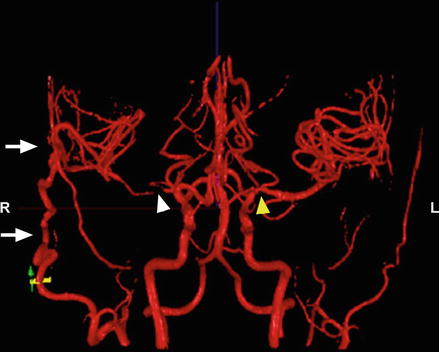

Figure 10.4

NOVA MRI shows flow through right STA-MCA bypass (arrows) filling the brain on the right side. Note the absence of the MCA on the right side (white arrow head) and mild narrowing of the MCA on left side (yellow arrow)

Figure 10.5

CT angiogram shows moyamoya on the right with closure of the ICA (red arrow) and a normal blood vessel on the left (yellow arrow)

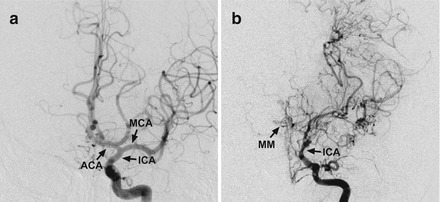

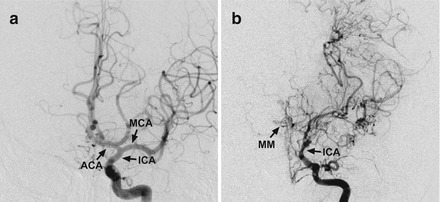

Figure 10.6

Cerebral angiogram. (a) Front view of a normal angiogram. (b) Front view of an angiogram showing moyamoya disease. Note the narrowing of the ICA and presence of moyamoya vessels. Also note the absence of the MCA and ACA. ICA internal carotid artery, ACA anterior carotid artery, MCA middle cerebral artery, MM moyamoya collateral arteries

Several different brain perfusion studies help determine how well blood vessels deliver oxygen to tissues of the brain. Patients may undergo one or more of these studies to evaluate brain perfusion, such as MRI, CT, PET and Xenon CT (Fig. 10.7) which, when combined with clinical history and physical evaluation, help guide treatment recommendations. Cognitive evaluation is also frequently done to assess for executive dysfunction (disorganization and impaired focus), which has been shown to be present at higher rates in adult moyamoya patients even without prior stroke [4, 12, 13].

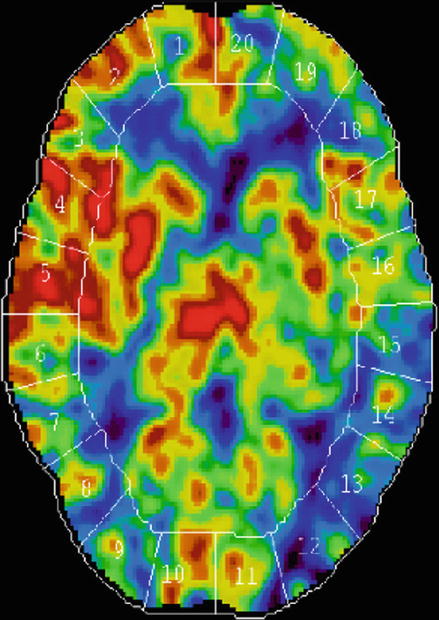

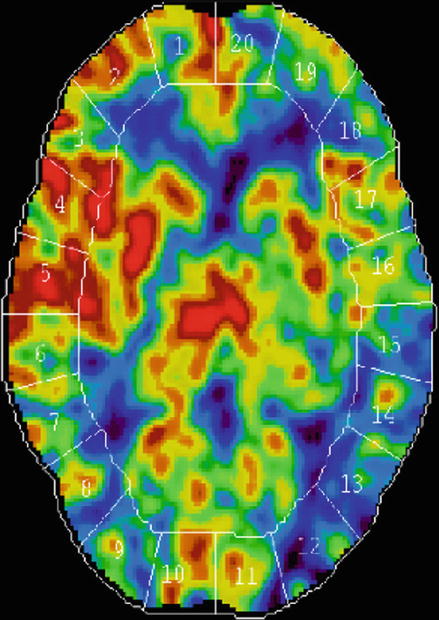

Figure 10.7

Xenon CT scan: This perfusion study shows reduced blood flow (higher area of blue) on the left side compared with normal perfusion on right side (higher area of red)

Treatment

Moyamoya is sometimes treated with antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy in an attempt to improve blood flow to the brain. However, as previously mentioned, medical therapy alone is ineffective. The goal of treatment is to improve blood flow to the brain and prevent future stroke. Placement of stents, often effective against intracranial atherosclerosis, are ineffective against moyamoya long-term due to its lack of atherosclerotic etiology and progressive nature [16]. As most patients are young when moyamoya is diagnosed, surgery is usually recommended when symptomatic.

Surgical procedures include direct and indirect revascularization techniques. The direct bypass is known as the superficial temporal artery to middle cerebral artery (STA-MCA) bypass. This involves attaching a scalp artery (STA) directly into a brain artery (MCA) on the outer surface of the brain. Patients benefit from an immediate improvement in their blood flow when the bypass is completed as well as reduced risks of stroke. Indirect bypasses (encephalo-duro-synangiosis [EDAS], encephalo-duro-arterio-myo-synangiosis [EDAMS], pial synangiosis) involve placing a scalp artery or vascular muscle or tissue on the outer surface of the brain for gradual growth of blood supply inwards to areas in need. At least several months are required for ingrowth of new blood supply as well as stroke risk reduction using this method alone.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree