4 | Multilevel Cervical Spondylosis: Posterior Approach |

| Case Presentation |

History and Physical Examination

W.S. is an 80-year-old man presenting with a 1-month history of decreasing ability to ambulate and an inability to perform independent activities of daily living. He was noted to have weakness in his upper and lower extremities with worsening of his manual dexterity bilaterally. He denied bowel and bladder dysfunction.

On physical exam, the patient’s neck range of motion was limited but not painful (flexion to 25 degrees, 10 degrees of extension, and 25 degrees of rotation bilaterally). He was able to ambulate short distances with assistance utilizing a wide-based gait. He noted radiating pain down his left arm, particularly in the dorsum of his forearm distally. Hoffmann sign was positive bilaterally. The patient was hyperreflexic in both the upper and the lower extremities with equivocal Babinski responses and four beats of nonsustained clonus bilaterally.

Figure 4–1 Sagittal magnetic resonance imaging showing spondylosis and stenosis affecting multiple levels with maintenance of cervical lordosis.

Radiological Findings

The patient’s sagittal and axial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is shown in Figs. 4–1 and 4–2. There is significant central canal stenosis with disk protrusions at C3-4, C4-5, C5-6, and C6-7. There is maintenance of sagittal cervical lordosis. The axial MRI (Fig. 4–2) at the C5-6 level demonstrates significant foraminal stenosis on the left side.

Diagnosis

The patient was diagnosed clinically as having evidence of progressive myeloradiculopathy with significant neurological compromise involving the ability to ambulate as well as a loss of manual dexterity. Radiographs confirmed multilevel cervical spondylosis with central stenosis and preservation of cervical lordosis with significant left-sided, C5-6 foraminal stenosis.

Figure 4–2 Axial magnetic resonance imaging at the C5-6 level showing significant left-sided, foraminal stenosis.

| Background |

Cervical spondylosis is a degenerative disease of the spine characterized by a loss of disk height, end plate sclerosis, and osteophyte formation. By age 70 years, 70% of women and 95% of men may have these radiographic changes.1 Most often, these changes do not result in neurological symptoms. However, a certain percentage of people manifest symptoms of either or both radiculopathy and myelopathy.

Age-related degeneration is most prevalent at the C5-6 level, followed by C6-7 and C4-5.2 Various anatomical structures are affected, resulting in a constellation of radiographic findings. Facet and uncovertebral degeneration as well as decreased disk height with osteophytic formation are the most common anatomical findings. As the degeneration becomes more significant, central and foraminal stenosis may ensue, resulting in clinical symptoms of myelopathy, radiculopathy, or both.

Clarke and Robinson reported that the natural history of cervical spondylotic myelopathy is progressive, with 75% of patients deteriorating in a stepwise fashion, 20% deteriorating slowly and steadily, and 5% having a rapid onset of symptoms.3 Because of the unfavorable natural history of the disease and the unpredictable rate of neurological deterioration, surgical treatment is recommended in an attempt to prevent further neurological loss.

Posterior cervical laminoplasty was developed as a technique to address the high rate of myelopathy found in the Japanese population secondary to multilevel ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL). Hattori is credited with first developing the technically demanding Z-shaped laminoplasty in 1971, which was later reported in the American literature.4,5 Hirabayashi et al described the open-door laminoplasty, which is the basis for our preferred technique.4,6

Results of laminoplasty in select patients have been favorable. Herkowitz retrospectively reviewed anterior fusions versus laminectomy versus laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic radiculopathy7 and found that ACDF and laminoplasty were statistically better than laminectomy for pain relief (92% vs 86% vs 66% excellent-to-good results for ACDF, laminoplasty, and laminectomy, respectively). Seichi et al reported that 84% of patients undergoing laminoplasty for multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy maintained good results by an improvement in the Japanese Orthopaedic Association scores at an average of 156 month follow-up.8 Satomi et al found that Japanese Orthopaedic Association scores improved for up to 3 years postoperatively, and canal diameter remained enlarged at 5 years of follow-up.9 Yonenobu et al compared 41 patients who underwent anterior corpectomy and strut grafting with 42 patients who underwent laminoplasty for cervical myelopathy with a minimum 2-year follow-up.10 Neurological recovery was similar for both groups; however, surgical complications were higher in the anterior corpectomy group, including 10 graft complications (dislodgment, fracture, and pseudarthrosis), four patients with neurological deterioration, one esophageal fistula, and one retrolisthesis. Only three transient palsies of C5 were noted in the laminoplasty group. A 10- to 14-year follow-up was reported in this same cohort.11 Twenty-three patients in the anterior corpectomy group (average 2.5 levels) were compared with 24 patients who underwent laminoplasty. In terms of results, long-term neurological recovery was comparable, but the complication rate in the anterior corpectomy group was much higher.

Heller et al reported an independently matched clinical cohort of multilevel cervical laminectomy with fusion patients versus laminoplasty patients.12 They found a significantly reduced rate of postoperative complications, including nonunions, instrumentation failure, and infections in the laminoplasty group. Additionally, the authors noted no difference in rates of neurological and functional outcomes. As such, laminoplasty with foraminotomy is the authors’ preferred technique to address multilevel cervical spondylotic myeloradiculopathy in patients who have a neutral or lordotic cervical alignment with no evidence of instability.

| Authors’ Preferred Method of Surgical Management |

Laminoplasty and Foraminotomies

Positioning

If the patient is significantly myelopathic with evidence of spinal stenosis, it is the authors’ recommendation to perform an awake fiberoptic intubation confirming movement of the extremities prior to delivery of the anesthetic. Baseline somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs) and motor evoked potentials (MEPs) are obtained prior to positioning on the operating table. Once confirmed, Mayfield tongs are placed and the patient is transferred onto a regular operating room table in the prone position. The chest is aligned on chest rolls that allow the chin to clear the operating room table by ~10 cm. When multilevel spondylosis is present, extension of the neck should be avoided to prevent buckling of the ligamentum flavum and further narrowing of the canal.13 It is the authors’ preference that the neck is positioned in slight flexion to open the interlaminar spaces and prevent pincering of the spinal cord.

Visualization of the lower levels of the cervical spine with radiography can be difficult. To facilitate this, the shoulders can be secured to the operating table with tape while gentle traction is placed in a caudal direction on the arm. Care must be taken not to use excessive traction because a brachial plexus palsy may ensue. Foam tape can be placed on the shoulders prior to the application of cloth tape to improve holding strength and prevent skin breakdown.

The head of the table is elevated ~10 degrees to allow for venous drainage of the epidural veins during canal expansion. Baseline SSEPs are reobtained prior to the surgical prep to confirm that there has been no interval change during positioning.

Exposure

The spinous processes of C2, C7, and T1 are large, can be easily palpated, and serve as anatomical landmarks prior to incision. The incision is made in the midline extending from C2 to T1. Bovie electrocautery is used to dissect down to the fascia. The avascular ligamentum nuchae is identified in the midline and divided en route to the spinous processes. The internervous plane is between the left and right paracervical muscles (which are supplied segmentally by the left and right posterior rami of the cervical nerves). Once the spinous processes are reached, subperiosteal dissection is extended laterally to the junction of the lateral mass and lamina. Overzealous lateral retraction should be avoided to minimize bleeding from the paraspinal musculature.

If a fusion is not anticipated, the exposure can be performed to the medial edge of the lateral masses to avoid disruption of the facet capsules. If a fusion is being performed, the facet capsules can be resected, and exposure should be extended to the lateral border of the lateral masses. If the surgical procedure does not include intervention above C2, care should be taken to preserve the muscular attachments of rectus capitis posterior major and minor, and the oblique capitis superior and inferior. Detachment of these muscles has been shown to be a significant risk factor for developing long-term kyphosis.14 If detachment does occur, a formal repair with nonabsorbable suture and drill holes through the C2 laminar arch should be performed.

Foraminotomy

Prior to laminoplasty, we recommend performing foraminotomies at those levels that have radiographic evidence of stenosis. We prefer performing the foraminotomy on the opening side of the laminoplasty. It is also the authors’ preferred method to perform a French-door laminoplasty in the setting of bilateral neuroforaminotomies to preserve as much facet joint as possible.

To perform an adequate foraminotomy, the surgeon must have a thorough understanding of the borders of the neuroforamen. The superior and inferior borders of the foramen are composed of the pedicles of the vertebral body above and below. The roof of the foramen is the superior articular facet. The floor of the foramen is the disk.

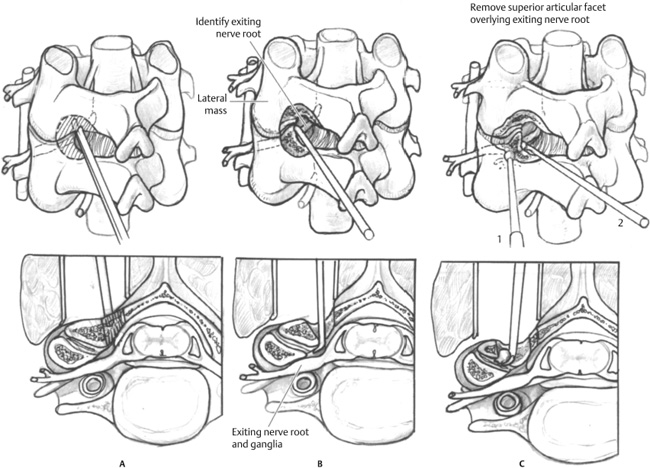

The technique for a posterior foraminotomy is depicted in Fig. 4–3. First, a 2 mm Kerrison rongeur (Specialty Surgical Instrumentation, Inc., Nashville, TN) is used to remove a portion of the superior lamina. Then a high-speed burr is used to enter the canal medially while the bone is thinned laterally toward the facet joint. We prefer using a 3 mm round, soft-tipped cutting burr. The overlying inferior articular facet and the superior articular facet are burred until they are thin enough to elevate with a small, angled curette. The decompression is performed laterally such that less than 50% of the facet joint is resected. Every attempt is made to complete the foraminotomy with an angled curette to avoid placement of the thicker Kerrison into the already narrowed foramen.

Figure 4–3 Posterior cervical foraminotomy. (A) A Kerrison rongeur is used to perform a laminotomy. (B) A burr is used to perform a medial facetectomy or foraminotomy, and a nerve hook is passed through the foramen to check for adequacy of decompression. (C) A foraminotomy should be extended laterally until the nerve root is decompressed.