Chapter 5 Multiple sclerosis

Pathology

The other conditions that are part of this group are rare and may be variants of MS. They include:

The demonstration that a serum autoantibody present in neuromyelitis optic (Lennon et al., 2004), subsequently shown to be an IgG antibody binding to the aquaporin-4 water channel (Lennon et al., 2005), allows a clear distinction to be made between most people with MS and the majority of those whose clinical pattern involves the optic nerves and spinal cord. It is possible that better understanding of the pathology and immunology of the demyelinating diseases will result in the recognition and identification of other clinical sub-types of the disease.

Demyelination of nerve fibres

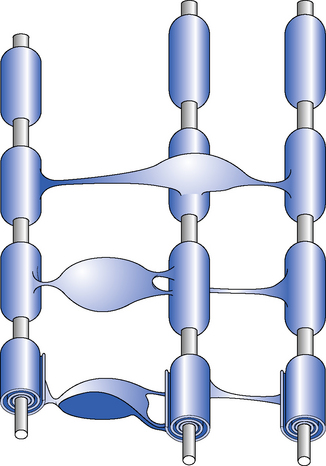

In the CNS, myelin is produced by oligodendrocytes (Shepherd, 1994). Each oligodendrocyte gives off a number of processes to ensheath surrounding axons. These processes, which envelope the axon, form a specialized membranous organelle – the myelin segment. A myelinated nerve fibre has many such myelin segments, all ofa similar size, arranged along its length. Between the myelinated segments there is an area of exposed axon known as the node of Ranvier. The myelin segment is termed the ‘internode’ (Figure 5.1). When an action potential is conducted along the axon, ionic transfer predominantly occurs across the axonal membrane at the node of Ranvier. The lipid-rich myelin of the internode insulates the axon and inhibits ionic transfer at the internode. This arrangement of segmental myelination allows rapid and efficient axonal conduction by the process of saltatory conduction where the signal spreads rapidly from one node of Ranvier to the next.

Distribution of plaques

The microscopic appearance of a plaque depends upon its age. An acute lesion consists of a marked inflammatory reaction with perivenous infiltration of mononuclear cells and lymphocytes (Lucchinetti et al., 1996). There is destruction of myelin and degeneration of oligodendrocytes with relative sparing of the nerve cell body (neurone) and the axon. Axonal integrity may be disrupted early in the inflammatory process and may be the most important determinant of residual damage and disability (Trapp et al., 1998). In older lesions there is infiltration with macrophages (microglial phagocytes), proliferation of astrocytes and laying down of fibrous tissue. Ultimately this results in the production of an acellular scar of fibrosis which has no potential for remyelination or recovery.

It is suggested by some pathologists that the variation seen in the appearance of individual plaques indicates hetrogeneity in the underlying pathology and differing immunological causes of MS (Lucchinetti et al., 2000).Others, however, feel that the variability in lesions may represent only a temporal progression of the pathology and that varying lesions are within the same individual (Prineas et al., 2001). It is evident that the pathology in people with primary progressive MS (PPMS) differs from that seen in relapsing remitting disease (RRMS) (Bruck et al., 2003).

Remyelination

Remyelination can occur following an acute inflammatory demyelinating episode. There are, within the brain, oligodendroglial precursors which can mature into oligodendrocytes, infiltrate the demyelinated area and provide partial remyelination of axons (Prineas & Connell, 1978). This can be demonstrated in postmortem tissue and, though remyelination always appears thinner than the original myelin, it may allow functional recovery.

Axonal damage

It is now recognized that during the acute inflammatory phase of the disease axonal transection and damage occurs in the demyelinating plaque (Trapp et al., 1998).In the later stages of the disease, and in addition to the scarring which develops at the site of the inflammatory plaques, there is increasing damage to the axons which can be seen both at the site of the original inflammation and distant from the areas involved in the original inflammation. It is likely that this axonal damage is an important part of the pathology of MS and, though less well recognized and researched than demyelination, is probably responsible for the more progressive and chronic forms of the illness. This axonal loss can be demonstrated on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans as atrophy of the brain white matter, ventricular dilatation, ‘black holes’ and degeneration of the long ascending and descending tracts of the brainstem and spinal cord. Brain atrophy is also the main morphological counterpart of psychological deficits and dementia occurring in people with MS (Loseff et al., 1996).

Aetiology and epidemiology

Geographical prevalence

Epidemiological research into MS has been bedevilled by problems with ascertainment, identification of the baseline population to estimate prevalence, and the difficulty in interpreting minor changes in the small numbers of patients identified. Nonetheless, there appears to be a reproducible finding that the prevalence of MS varies with latitude (see Langton Hewer, 1993, for a review). In equatorial regions the disease is rare, with a prevalence of less than 1 per 100 000, whereas in the temperate climates of northern Europe and North America this figure increases to about 120 per 100 000 and in some areas as high as 200 per 100 000. In the UK it has a prevalence of about 80 000, affecting approximately 120 in every 100 000 of the population (O’Brien, 1987).

There is a similar, but less clearly defined relationship of increasing prevalence with latitude in the southern hemisphere. Some regions with the same latitude have widely differing prevalence of MS; Japan has a relatively lower incidence, whereas Israel has an unexpectedly high level; the two Mediterranean islands of Malta and Sicily have a 10-fold difference in prevalence. Studies within the USA appear to confirm this variation with latitude but may in part reflect genetic differences in the origin of the populations, predominantly derived from European Caucasians (Page et al., 1993).

Genetic influences

A familial tendency towards MS is now well established but no clear pattern of Mendelian inheritance has been found. Between 10 and 15% of people with MS have an affected relative, which is higher than expected from population prevalence. The highest concordance rate is for identical twins – about 30%; non-identical twins and siblings are affected in 3–5% of cases. Children of people with MS are affected in about 0.5% of cases (Ebers et al., 1986).

A genetic factor is supported by the excess of certain major histocompatibility (MHC) antigens in people with MS. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) A3 and B7 are overrepresented in people with MS and the HLA complex on chromosome 6 has been considered as the possible site of an MS ‘susceptibility gene’. Systematic genome screening to attempt to define the number and location of susceptibility genes has been undertaken (Sawcer & Compston, 2003) and the most obvious candidates are DR(2)15 and DQ6, the former genotype is now defined as DRB1⁎1501, DRB5⁎0101 and the latter DQA1⁎0102, DQB2⁎0602. More recently assocation has been suggested with genes encoding the cytokines IL2 (Matesanz et al., 2004) and IL7 (Lundmark et al., 2007); almost all genes so far identified affect the immune system. Recently an axonal gene, KIF1B, has been identified to carry a susceptibility risk (Aulchenko et al., 2008). The probability is that, as in the case of diabetes mellitus, any genetic factor in MS is likely to involve several different genes and be complex (Compston, 2000).

Viral ‘epidemic’ theory

One other intriguing aspect of epidemiology of MS is the so-called ‘epidemics’ of MS occurring in the Faroes, the Orkney and Shetland Islands, and Iceland in the decades following the Second World War (Kurtzke & Hyllested, 1986). It was suggested that the occupation troops may have introduced an infective agent which, with an assumed incubation period of 2–20 years, resulted in the postwar ‘epidemic’. It should be emphasized that despite extensive research no such infective agent has ever been isolated. Several factors influence the accuracy of such research and one or two errors in the numerator, when defining the base population, would make huge differences in the interpretation of the data.

Migration studies have lent support to the possibility of incomers adopting the risk and prevalence of MS closer to their host population. Studies have suggested that when migration occurs in childhood, the child assumes the risk of the country of destination, but these studies rely upon relatively small numbers of defined cases and interpretation is difficult (Dean & Kurtzke, 1971).

Clinical manifestations

There are different types of MS, which are classified in Table 5.1. The disease can run a benign course with many people able to lead a near-normal life with either mild or moderate disability.

Table 5.1 Classification of multiple sclerosis

| Classification | Definition |

|---|---|

| Benign MS | One or two relapses, separated by some considerable time, allowing full recovery and not resulting in any disability |

| Relapsing remitting MS | Characterized by a course of recurrent discrete relapses, interspersed by periods of remission when recovery is either complete or partial |

| Secondary progressive MS | Having begun with relapses and remissions, the disease enters a phase of progressive deterioration, with or without identifiable relapses, where disability increases even when no relapse is apparent |

| Primary progressive MS | Typified by progressive and cumulative neurological deficit without remission or evident exacerbation |

MS, multiple sclerosis.

MS can also be classified according to the certainty of diagnosis (Table 5.2). It should always be remembered that the diagnosis is one of exclusion; haematological and biochemical investigations are essential to rule out other confounding diseases and, during the course of the disease, the physician must always be willing to reconsider the possibility of differential diagnosis. The classification of disease by the certainty of the diagnosis is of predominant importance for the inclusion of patients into drug trials and for epidemiological studies (McDonald et al., 2001; Poser et al., 1983). Recently an updated classification of diagnostic criteria has been produced (Polman et al., 2005) and this is currently being assessed.

Table 5.2 Classification of multiple sclerosis according to certainty of diagnosis

| Clinically definite MS | Two attacks and clinical evidence of two separate lesions Two attacks; clinical evidence of one lesion and paraclinical evidence of another separate lesion |

| Laboratory-supported definite MS | Two attacks; either clinical or paraclinical evidence of one lesion and CSF oligoclonal bands One attack; clinical evidence of two separate lesions and CSF oligoclonal bands One attack; clinical evidence of one lesion and paraclinical evidence of another, separate lesion and CSF oligoclonal bands |

| Clinically probable MS | Two attacks and clinical evidence of one lesion One attack and clinical evidence of two separate lesions One attack; clinical evidence of one lesion and paraclinical evidence of another, separate lesion |

| Laboratory-supported probable MS | Two attacks and CSF oligoclonal bands |

Paraclinical evidence is derived from magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomographic scanning or evoked potentials measurement. CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; MS, multiple sclerosis.

Early signs and symptoms

Neurological deficit

Not infrequently the disease may begin with the signs and symptoms of cerebellar dysfunction causing unsteadiness, imbalance, clumsiness and dysarthria (slurring of speech). Examination may reveal the patient to have nystagmus (a jerky movement of the eyes), an intention tremor (see Ch. 4) and a cerebellar dysarthria, the combination of which is termed Charcot’s triad and is one of the classical features of MS. These symptoms are due to demyelination occurring within the brainstem and there are a wide variety of brainstem syndromes causing cranial nerve disturbances and long tract signs. Other clues are the development of trigeminal neuralgia, or tic douloureux (sharp facial pains), in young adults suggesting the presence of a lesion within the brainstem.

Possible signs and symptoms in the course of multiple sclerosis

Psychiatric and psychological disturbances are common (see Ch. 17). Depression is the most common affective disturbance in MS and may compound the underlying physical problems, exaggerating symptoms of lethargy and reduced mobility. With diffuse disease some people develop frank dementia, a few become psychotic and epileptic seizures are seen in 2–3% of cases, an increase of four to five times over that of the normal population. Patients can show evidence of emotional instability or affective disturbance. Euphoria, or inappropriate cheerfulness, was said to be a classical feature of the disease but this is now considered a myth. It is, in practice, quite rare and probably occurs when lesions affect the subcortical white matter of the frontal lobes, resulting in an effective leucotomy.

Patients will frequently record an increase in their symptoms with exercise and with a rise in body temperature. The physiology behind these symptoms is probably the same, due to the fact that the propagation of an action potential along a neurone is greatly affected by temperature. Nerve conduction in an area of demyelination can be critical and paradoxically an increase in temperature, which normally improves conduction, may, in the demyelinated axon, result in a complete conduction block. This phenomenon of worsening of symptoms with exercise and increased temperature is Uhthoff’s phenomenon and is most dramatically manifest when patients describe how they are able to get into a hot bath but not able to extricate themselves. Patients should be warned to avoid extremes of temperature and overexertion to avoid this increase in symptoms (Costello et al., 1996).

Diagnosis

To make a clinical definitive diagnosis of MS there has to be a history of two attacks and evidence, clinically, of two separate lesions (Poser et al., 1983). It is also important to remember that other diagnoses should be excluded and, since at presentation all these criteria may not be fulfilled, corroborative paraclinical, laboratory and radiological evidence is usually sought (see O’Connor, 2002, for a review).

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI of the head and spinal cord is extremely useful in demonstrating the lesions of MS (see Figure 2.2 in Ch. 2). Typically, high signal lesions on T2-weighted sequences are seen throughout the white matter. Gadolinium enhancement demonstrates areas of active inflammation with breakdown in the blood–brain barrier, which are associated with an acute relapse (Paty et al., 1988). In particular circumstances, as with acute optic neuritis or cervical myelopathy, the demonstration on an MRI scan of disseminated asymptomatic lesions is particularly helpful in confirming the diagnosis and there are rigid criteria for interpreting the MRI scan changes. Newer techniques, such as fluid-attentuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and magnetization transfer imaging (MTI), improve the sensitivity and selectivity of MRI in MS (Filippi et al., 1998).

Lumbar puncture

Analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in a patient suspected of having MS is valuable diagnostically. There is production of immunoglobulin (mainly IgG) within the CNS and these antibodies are detected by biochemical analysis of the CSF. Electrophoresis of the CSF allows the immunoglobulin fraction to separate into a few discrete bands (oligoclonal bands) and simultaneous analysis of the immunoglobulin from the blood can demonstrate that these antibodies are confined to the CNS and, therefore, provide confirmatory evidence of inflammatory CNS disease (Tourtellotte & Booe, 1978).

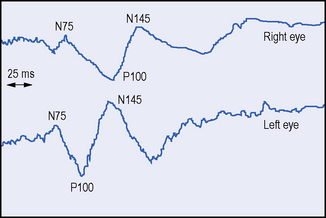

Evoked potentials

A typical history, the signs of more than one lesion affecting the CNS, together with disseminated white-matter lesions shown on MRI and the presence of unmatched oligoclonal bands in the CSF, puts the diagnosis beyond reasonable doubt. However, when one or more of these findings are inconclusive further support for the diagnosis may be obtained by evoked potential (EP) testing (Misulis, 1993) (Figure 5.2). These tests, which include visual, brainstem auditory and somatosensory evoked potentials (VEP, BAEP, SSEP) may provide evidence of a subclinical lesion, which has previously been undetected (Halliday & McDonald, 1977). For example, the finding of abnormal SSEPs from both legs, in a patient presenting with blindness in an eye, strongly suggests a lesion in the spinal cord and raises the possibility of MS. The demonstration of more than one lesion is essential in making a secure diagnosis of MS.

The management of multiple sclerosis

Not all MS patients require active intervention but even those with mild symptoms should be given support and advice from appropriate professionals, relevant to the patient’s condition and circumstances. Interventions available for those with moderate to severe disabilities mainly involve drug therapy and physiotherapy. For a recent review of the management of MS, see O’Connor (2002).

There is no proven benefit from any dietary restrictions, though there is suggestive evidence that diets low in animal fat and high in vegetable oil and fish-body oil have potential benefits (Klaus, 1997; Payne, 2001).

Drug therapy

The management of the acute exacerbation

Corticosteroids hasten recovery from an acute exacerbation of MS and improve rehabilitation. The most commonly used agent is intravenous methylprednisolone (Martindale, 2007).

There is some evidence that the use of steroids in early acute symptoms of MS, specifically optic neuritis, may retard the development of MS during the next 2 years (Beck et al., 1993). However, the use of long-term steroids has no effect on the natural history of the disease and the risks outweigh any benefit.

Symptomatic drug therapy

The effective use of symptomatic agents is intended to make the life of the person with MS more tolerable (Thompson, 2001).

Spasticity

Tizanidine (Zanaflex) is another centrally acting agent which is less sedating and has less of an underlying effect on muscle than baclofen but is potentially hepatotoxic (Martindale, 2007). Again it must be used by titration against the symptoms and spasticity in the individual patient and is used together with physiotherapy to improve mobility.

In severe painful spasticity, where the aim is to alleviate the distressing symptoms or to aid nursing care rather than to restore function, there are a number of more invasive procedures which may be useful. Local injection of botulinum toxin causes a flaccid paralysis in the muscles injected, with minimal systemic side-effects. The effect usually lasts for 3 months and may be repeated indefinitely (Snow et al., 1990). More graduated doses of the toxin can improve mobility in people with less severe spasticity. The more destructive techniques of intrathecal or peripheral nerve chemical blocks, or surgery are now rarely required.

Pain

People with MS develop pain for a variety of reasons, some of which are central and some peripheral. Plaques affecting the ascending sensory pathways frequently cause unpleasant dysaesthesiae, or allodynia, on the skin, often with paraesthesiae. Such central pain is most responsive to centrally acting analgesics, such as the antiepileptics carbamazepine, sodium valproate or gabapentin. It may also respond to tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitriptyline or dothiepin. Alternatively, electrostimulation with cutaneous nerve stimulation (see Ch. 12) or dorsal column stimulation (Tallis et al., 1983) can be effective.

Cannabis is thought to be helpful for MS patients but is not used widely and is currently under investigation. Principles of pain management are discussed in Chapter 16.

Bladder, bowel and sexual dysfunction

These symptoms, which often occur in combination, are due to spinal cord disease and have a major impact upon the patient (see Barnes, 1993, for a review).

Sexual dysfunction

Erectile dysfunction in men is a common problem and is now helped by the use of sildenafil, which has been demonstrated, in a randomized placebo controlled trial, to be effective (DasGupta & Fowler, 2003). Alternative methods are still available, but the use of intracorporeal papaverine has now been replaced by prostaglandin.

In women there are many factors which may affect the expression of sexuality, including neurological symptoms from sacral segments, such as diminished genital sensitivity, reduced orgasmic capacity and decreased lubrication (Hulter & Lundberg, 1995).

Both sexes are affected by leg spasticity, ataxia, vertigo and fatigue. Counselling may be appropriate in some cases and referral to a specialist counselling service, such as SPOD, may be useful (see Appendix 2 ‘Associations & Support Groups’).

Fatigue

Almost all patients with MS will, at some time, complain of fatigue and in the majority of cases it is regarded as being the most disabling symptom. Pharmacological treatment is disappointing, though amantidine and pemoline have been suggested to be beneficial. Other agents used in the past have now been replaced by the less addictive modafinil. Reassurance and graded exercise programmes are considered to be at least as effective (see ‘Physical management’, below). There has been the recent suggestion that use of a long acting form of 4 aminopyridine, a sodium channel blocker, has a benefit in reducing fatigue (Goodman et al., 2008).

Tremor

The treatment of tremor in MS, as in most other situations, is difficult (see Ch. 14). Minor action tremors may be helped by the use of beta-blockers, such as propranolol, or low-dose barbiturates such as primidone. The more disabling intention tremor of cerebellar disease and the most disabling dentatorubral thalamic tremor, which prevents any form of movement or activity, is refractory to treatment. There have been reports of agents such as clonazepam, carbamazepine and choline chloride helping individuals, and by serendipity, the antituberculous agent isoniazid has been shown to be effective but should be given with a vitamin B6 supplement. None of these treatments are particularly effective and the possibility of deep brain stimulation is now being increasingly considered. Surgical treatments are most effective for unilateral tremor; bilateral treatment is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

Psychological symptoms

Depression is the most common symptom and, if clinically significant, requires treatment with antidepressant medication, either a tricyclic agent or a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (Martindale, 2007). Cognitive dysfunction is reported to occur in up to 60% of patients. Psychological issues and behavioural management are discussed in Chapter 17.

Disease-modifying therapies

Three forms of immunomodulatory therapy, beta-interferon, glatiramer acetate and natalizumab, are licensed and have been shown in large controlled, randomized clinical trials to be effective in reducing the frequency and severity of relapses and delaying the development of disability in people with relapsing remitting MS. Immunosuppressive therapy has also received much attention. For a review of disease-modifying therapies, see Corboy et al. (2003).

Interferon-β

An initial trial, giving interferon β by intrathecal route, showed a reduction in attack rate and was followed by a large trial in North America using the bacterially derived product interferon β-1b (IFBN Multiple Sclerosis Study Group, 1993). This showed that high doses of interferon β-1b, given subcutaneously on alternate days, reduced clinical relapses by one-third over 2 years as compared to placebo. There was a dramatic reduction in the changes seen on the MRI scans in the treated group but the study was not powered to show an effect upon progression of disability (Paty & Li, 1993).

Subsequent studies using a mammalian cell-line-derived interferon β-1a have shown benefit, in both frequency of attack and in development of disability (Jacobs et al., 1996; PRISMS Study Group, 1998), and three agents are now available:

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree