11 Myasthenic Crisis Mark Sivak and Jennifer A. Frontera Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disease of the neuromuscular junction characterized by a T-cell dependent response targeted to the postsynaptic acetylcholine receptor or receptor-associated proteins. Weakness is confined to voluntary muscles (sparing smooth and cardiac muscle) and is variable in focus and degree. Breathing and swallowing may become significantly involved, with severe consequences leading to respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. Respiratory insufficiency due to MG is referred to as myasthenic crisis. Myasthenic crisis can present as a forme fruste of MG. It can begin with oropharyngeal weakness with or without appendicular symptoms and progress to crisis within hours to days, often in the context of infection or aspiration and occasionally following surgery. Half of patients with recently diagnosed MG will have a crisis within the first year and another 20% within the second year from diagnosis. Patients with long-standing MG are also at risk for crisis. Triggers include:

| Antibiotics | Aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, norfloxacin), macrolides (clarithromycin, erythromycin), ampicillin, clindamycin, colistin, lincomycin, quinine, tetracyclines |

| Anticonvulsants | Phenytoin, gabapentin |

| Antipsychotics | Chlorpromazine, lithium, phenothiazines |

| Anesthetics | Diazepam, chloroprocaine, halothane, ketamine, lidocaine, neuromuscular blocking agents (depolarizing agents such as succinylcholine have no efficacy in myasthenic patients), procaine |

| Cardiovascular | Beta blockers, bretylium, procainamide, propafenone, quinidine, verapamil, and calcium channel blockers |

| Ophthalmologic | Betaxolol, echothiophate, timolol, tropicamide, proparacaine |

| Rheumatologic | Chloroquine, penicillamine |

| Steroids | Prednisone, methylprednisolone, corticotropin |

| Other | Anticholinergics, carnitine, deferoxamine, diuretics, interferon α, iodinated contrast agents, narcotics, oral contraceptives, oxytocin, ritonavir and antiretroviral protease inhibitors, thyroxine |

History and Examination

History

Does the patient have a history of MG? If so, has the patient been in crisis before? What were the triggers for the previous crises? Has the patient been intubated or had a tracheostomy (may indicate a more difficult airway) in the past? What medications is the patient taking? Have new medications been introduced or tapered? Does the patient have an infection or recent surgery?

Below are signs and symptoms of developing crisis in order of development:

- Deteriorating articulation

- Swallowing difficulty

- Accumulation of oral secretions—wet voice

- Worsening cough efficacy/reduced ability to clear secretions with cough

- Speech shift to short sentences (deteriorating length of numbers able to count aloud using a single breath)

- Patient anxiety increased due to hypoxia

Physical Examination

Concerning exam findings include:

- Increasing respiratory rate

- Use of accessory muscles of respiration

- Decreased tidal volume

- Paradoxical breathing

- Increasing pulse and blood pressure (BP)

- Diaphragmatic breathing especially at night in rapid eye movement sleep (REM). Worsening neck flexion correlates with diaphragm dysfunction.

- Unable to be supine

- In patients without a history of MG: Examine mucous membranes for evidence of diphtheria, look for ticks (particularly in children), assess for evidence of excess cholinergic stimulation (salivation, lacrimation, diarrhea, excess urination, gastrointestinal [GI] upset, emesis).

Neurologic Examination

- Mental status: normal unless CO2 retention leads to inattentiveness

- Cranial nerves: ptosis, nasal voice, ophthalmoparesis (diplopia), facial weakness, fatigable chewing, dysarthria, hypophonic voice, difficulty swallowing with pooling of secretions, no pupillary involvement

- Motor: fatiguing proximal >distal weakness, arm >leg weakness, neck flexor weakness (C3-C5) correlates with respiratory capacity

- Sensory: normal

- Reflexes: normal to slightly decreased

- Cerebellar: normal (exam may be limited by weakness)

- Additional testing: ptosis time (have patient look up and time how long it takes for ptosis to develop), arm abduction time (duration patient can keep arms abducted), one breath counting. These measures can be used to track improvement or worsening.

Differential Diagnosis

- Myasthenic crisis

- Cholinergic crisis. Can occur from excess acetylcholine esterase inhibitor. Characterized by SLUDGE (salivation, lacrimation, urination, diarrhea, (GI) upset, and emesis), miosis, bronchospasm, and flaccid weakness. Although a Tensilon (Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Aliso Viejo, CA) challenge can distinguish cholinergic crisis from myasthenia, this test can be dangerous and often is not necessary.

- Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome. Presynaptic autoimmune attack of voltage-gated calcium channels, associated with cancer in 50 to 70% (typically small cell lung cancer), limb symptoms more prominent than ocular/bulbar symptoms (5% with bulbar findings), facilitation with exercise, autonomic dysfunction, and reduced reflexes. Respiratory failure is uncommon.

- Botulism. Neurotoxin produced from Clostridium botulinum, permanently blocks presynaptic acetylcholine release at the neuromuscular junction. Botulism causes symmetrical descending paralysis with dilated pupils (50%), and dysautonomia, but no sensory deficits. Botulism can be treated with trivalent equine antitoxin.

- Tick paralysis. Ascending paralysis, ophthalmoparesis, bulbar dysfunction, ataxia, reduced reflexes. Complete cure can occur with tick removal.

- Organophosphate toxicity (malathion, parathion, Sarin, Soman, etc.). Inactivates acetylcholine esterase, causing SLUDGE, miosis, bronchospasm, blurred vision, and bradycardia. Also causes confusion, optic neuropathy, extrapyramidal effects, dysautonomia, fasciculations, seizures, cranial nerve palsies, and weakness due to continued depolarization at the neuromuscular junction. Delayed polyneuropathy can occur 2 to 3 weeks after exposure. Treat with atropine, pralidoxime (2-PAM), and benzodiazepines. Avoid succinylcholine.

- Guillain-Barré syndrome (see Chapter 12). Can present with areflexia and ophthalmoplegia (Miller-Fisher variant), or ascending weakness, facial weakness, diplopia, and areflexia. Often demyelinating, but can be axonal. Characterized by early loss of F waves on electromyogram (EMG). Treatable with plasmapheresis or intravenous high-dose immunoglobulin (IVIG).

- Neurotoxic fish poisoning. Tetrodotoxin (pufferfish) and saxitoxin (red tide) both block neuromuscular transmission. Ciguatera toxin (red snapper, grouper, barracuda) affects voltage gated sodium channels of muscles and nerves and produces a characteristic metallic taste in the mouth and hot-cold reversal.

- Diphtheria, caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae. It is associated with a thick gray pharyngeal pseudomembrane, atrial-ventricular (AV) block, endocarditis, myocarditis, lymphadenopathy, neuropathy with craniopharyngeal involvement, proximal >distal weakness, and decreased reflexes.

- Myopathy. Critical illness myopathy/neuropathy, mitochondrial myopathies (myoclonic epilepsy associated with ragged red fibers [MERRF]), acid maltase disease (adult type), polymyositis, and thyroid disease (Graves) can mimic MG.

- Brainstem disease with multiple cranial neuropathies (stroke, Bick-erstaff-Cloake, rhombencephalitis, basilar meningitis, carcinomatous meningitis)

- Diphtheria, caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae. It is associated with a thick gray pharyngeal pseudomembrane, atrial-ventricular (AV) block, endocarditis, myocarditis, lymphadenopathy, neuropathy with craniopharyngeal involvement, proximal >distal weakness, and decreased reflexes.

Life-Threatening Diagnosis Not to Miss

- Impending respiratory failure due to progressive neuromuscular disorder

- Organophosphate toxicity or botulinum toxicity, which can be treated with an antidote if administered in a timely fashion

Diagnostic Evaluation

In patients diagnosed with myasthenia gravis:

- Laboratory and radiographic studies: Complete blood count (CBC); chemistry panel; liver function tests; chest radiograph (CXR); erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR); C-reactive protein (CRP); blood, sputum, and urine cultures should be considered in febrile patients to identify an infectious source that may have led to decompensation. Serial ABGs should be performed. The first laboratory sign of respiratory insufficiency is a rising PCO2. By the time hypoxia is evident, respiratory failure is imminent.

- Respiratory function studies: Frequent (every 2 to 6 hours) vital capacity (VC) and negative inspiratory force (NIF) should be measured. A declining NIF or NIF worse than -20 cm H2O and VC <10 to 15 mL/kg should prompt intubation.

In patients without a diagnosis of myasthenia gravis:

- Bedside tests: Edrophonium (Tensilon) has a rapid onset and can be used to make the diagnosis of MG in patients with obvious ptosis; 2 mg doses can be administered every 60 seconds (up to 10 mg) while looking for a clinical response. Patients should receive electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring with atropine at the bedside while this test is being performed because of the risks of bradycardia. Because edrophonium has muscarinic effects, it can cause bronchospasm and increased secretions and is not recommended in those with crisis.

- Serologic studies: Acetylcholine receptor antibodies are present in 85% of patients with generalized MG. Rare false-positives can be seen in Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome, motor neuron disease, polymyositis, primary biliary cirrhosis, lupus, thymoma without MG, and in first-degree relatives of a myasthenic patient. Fifteen to 20% of patients with MG are seronegative. Of these patients, 40 to 50% have muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK) antibodies.

- Laboratory studies: Because many patients with MG have other autoimmune diseases, testing for lupus, thyroid disease, and rheumatoid arthritis is suggested. Lumbar puncture is typically unrevealing in MG.

- EMG: Repetitive nerve stimulation can be performed by administering 2 to 3 Hz stimulation and assessing for a decremental response in compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitudes. An exercise protocol can be applied to increase the sensitivity of the test. Single-fiber EMG is the most sensitive test for MG. Abnormal jitter can occur in other neuromuscular disorders but is specific for a disorder of neuromuscular transmission when no other abnormalities are seen on standard EMG needle exam. EMG/nerve conduction study (NCS) can distinguish MG from other neuropathies (diphtheria, Guillain-Barré, toxic neuropathy, etc.), presynaptic neuromuscular junction disorders (Lambert-Eaton, botulism, neurotoxic fish poisoning), and myopathies.

- Imaging: Chest computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to screen for thymoma should be performed on all myasthenic patients. MRI of the brain may be necessary if a central brainstem etiology is suspected.

- Serologies: Serologies specific to certain disease etiologies are listed: Lambert-Eaton—P/Q type calcium channel-binding antibodies; botulism—serum and stool botulism toxin assay; organophosphate toxicity—measure plasma and red blood cell (RBC) cholinesterase levels; C. diphtheriae—culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of toxin, serum diphtheria antibodies.

Treatment

Ventilation

MG patients with deterioration or impending crisis should be admitted to an intensive care unit because respiratory deterioration can be rapid. Although patients may be unable to handle secretions, glycopyrrolate should only be used with extreme caution as it can lead to mucous plugging. VC and NIF should be measured every 2 to 6 hours, and prompt intubation should be performed when NIF is steadily declining or worse than -20 cm H2O and/or VC <10 to 15 mL/kg. The initial ventilator mode is typically “assist control/volume control.”

After the insult triggering the crisis has been addressed and the patient has received adequate disease modifying therapy, considerations for ventilator weaning can begin. The patient should meet weaning criteria delineated in Chapter 17. A bedside measure of the patients’ readiness for extubation is the ability to lift the head off the bed against resistance.

Pressure support can be used as a weaning mode, but a myasthenic patient should also undergo a T-piece or tube compensation trial prior to extubation. An example of a weaning protocol is below:

- Check NIF/VC early on the day of trial.

- if NIF is better than -20 cm H2O and VC > 900 mL without cholinesterase inhibitors (AchI), begin pyridostigmine at 0.5 mg IV every 3 hours.

- Place patient on T piece or tube compensation mode for 40 minutes, after the dose of pyridostigmine.

- if NIF is better than -20 cm H2O and VC > 900 mL without cholinesterase inhibitors (AchI), begin pyridostigmine at 0.5 mg IV every 3 hours.

- Continue to monitor patient (blood pressure [BP], pulse rate, respiratory rate).

- Repeat NIF, VC, at 1.5 to 2 hours following the dose of acetylcholine esterase inhibitor.

- NIF and VC should be better than initial values (NIF better than -30 cm H2O and VC >1 L).

- The patient should be comfortable with stable vital signs. If the patient fails to maintain the above parameters or fatigues, discontinue the weaning trial and place the patient back on a resting mode and discontinue acetylcholine esterase inhibitor.

- Repeat NIF, VC, at 1.5 to 2 hours following the dose of acetylcholine esterase inhibitor.

- Preparation for extubation:

- At the end of the second dose of AchI, check that the patient remains stable.

- Confirm that NIF and VC remain as above.

- At 1 hour into the third dose of AchI, extubate the patient after good suctioning.

- Continue to monitor the patient.

- At the end of the second dose of AchI, check that the patient remains stable.

Myasthenic-Specific Treatment

- Early in a crisis, pyridostigmine is typically held since it can increase secretions.

- Underlying diseases that may have triggered a crisis should be addressed (infection, tapering of immunosuppression etc.).

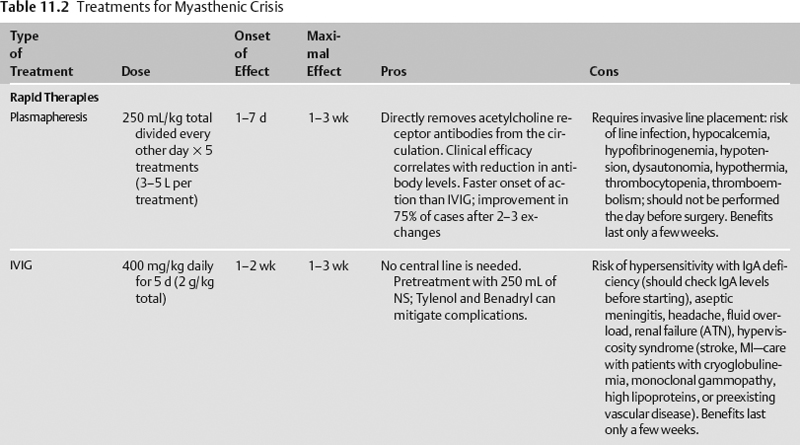

- Rapid treatment is initiated early with either plasmapheresis (plasma exchange) or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). Neither has been compared directly to placebo in a randomized clinical trial. Because plasmapheresis has a shorter onset of action, it is often the initial therapy used. In a prospective, randomized trial of plasmapheresis versus IVIG, 50% of patients reached a target improvement in the myasthenia muscle score by day 9 in the plasmapheresis group and by day 12 in the IVIG group, though there were no functional or strength differences by day 15, and there were fewer adverse events in the IVIG group.1

- Steroids are often begun concomitantly with rapid acting therapy because rapid therapy has a short duration of action. Steroids can seriously worsen weakness 5 to 10 days after initiation in up to 50% of patients and lead to respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation in 10%. However, the weakness produced by steroids typically lasts only 5 to 6 days and is blunted by concomitant rapid acting therapy.

- Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (pyridostigmine) can be restarted once a patient begins to show improvement from rapid therapy.

- Long-term steroid-sparing immunomodulating therapies are typically begun in the outpatient setting, though they may be started early, particularly in patients with a contraindication to steroids. These medications have a delayed onset of action (Table 11.2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree