Chapter 5 Native american and worldwide indigenous cultures

Who are indigenous people?

Definitions of indigenous

• Tribal peoples in independent countries whose social, cultural, and economic conditions distinguish them from other sections of the national community

• Peoples in independent countries who are regarded as indigenous on account of their descent from the populations that inhabited the country, or a geographical region to which the country belongs, at the time of conquest or colonization or the establishment of present state boundaries and who retain some or all of their own social, economic, cultural, and political institutions

Indigenous peoples of the world are very diverse (Bartlett, Madariaga, O’Neil, & Kuhnlein, 2007). They live in all countries and form a spectrum of humanity ranging from hunter-gatherers and subsistence farmers to professionals. In some countries, such as Bolivia and Peru, they form the majority of the population, whereas in many others they comprise small minorities. Some seek to preserve traditional lifestyles while others seek to adapt to a country’s mainstream. Despite extensive diversity in indigenous communities, all indigenous peoples (as defined by the ILO) have one thing in common: they all share a history of injustice and historical trauma. For many indigenous peoples, this historical trauma is cumulative emotional wounding across generations. It includes trauma from one’s own lifespan and trauma that emanates from massive group ordeals such as massacres, boarding school abuses, and intergenerational transfer of traumatic responses (Evans-Campbell, 2008). Indigenous peoples are the victims of violent crime more often than national averages (Greenfield & Smith, 1999) and experience overt and covert instances of racism. The historical trauma response is in reaction to intergenerational traumatic history. Of the 17,000 Cherokees forced to leave their ancestral homes in North Carolina and relocate in Oklahoma, 8000 died (Churchill, 1996). Both the Creek and Seminole nations suffered approximately 50% mortality in their relocations as well (Foreman, 1989). Nearly every tribe in the United States has its own story of relocation and warfare. Even as late as the 1950s, American Indians were relocated—this relocation moving them from traditional lands to urban areas. Australian Aborigines had similar experiences. In Australia, under a government policy that ran from 1910 to 1971, as many as 1 in 10 of all Aboriginal children were removed from their families and placed in orphanages or foster homes in an effort to “civilize” them by assimilation into white society. Boarding schools had an especially negative impact on the quality of indigenous parenting and the development of domestic violence in indigenous families. Parents who were traumatized as children often pass on trauma response patterns to their offspring, including violence. Gender roles and relationships were also impaired as indigenous children were taught values that women and children were the property of men and that the corporal punishment of children was acceptable. People who have been traumatized tend to pass on the trauma.

In the United States, indigenous groups include Native Hawaiians and American Indians/Alaska Natives. (The term Native American is used interchangeably with American Indian.) The American Indian population consists of Indians, Inuit, Yupic, and Aleuts. Specifically, “Who is an Indian?” in the United States, however, is a difficult question to answer because no single federal or tribal definition is used to determine membership in this population. Three definition categories have been applied: biological, administrative, and mystical. Biological definitions are usually based on some minimum “blood quantum” or percentage of “Indian blood” (e.g., one fourth, one eighth). Each Native American group has always had a name for itself, which often translates to something like “The People.” Official names have often been applied by outsiders, and often these names are now used by the Indians themselves. For example, the group known as Sioux is actually a number of related groups, including Ogala, Hunkpapa, and Yanktonia. The word Sioux comes from a French translation for a term applied to the group by their enemies, the Blackfoot, and means something like, “those who crawl in the grass like snakes.” The Creek got their name from English settlers describing the location of their settlements next to creeks. Those called Native American or American Indian often prefer to identify themselves using terms specific to their native groups, such as Nee-me-poo (Nez Perce) or Dineh or Diné (Navajo). Native Americans of one nation were and are as different from Native Americans of another nation as the English are from the Spanish or the Swedes are from Italians (Heinrich, 1991).

The population figures for indigenous peoples of the Americas before the 1492 voyage of Christopher Columbus have proved difficult to establish. Most scholars writing at the end of the 19th century estimated the pre-Columbian population at about 10 million; by the end of the 20th century, the scholarly consensus had shifted to about 50 million (Taylor, 2002). There is general agreement that a very large percentage of these peoples succumbed to diseases introduced by Europeans. As of July 1, 2008, the estimated population of American Indians and Alaska Natives was 4.9 million, including those of more than one race. They made up 1.6% of the total population (www .infoplease.com/spot/aihmcensus1.html#axzz0zzsJFDCu.)

Native Americans reside in every state of the United States. About three fourths of the population is found in the West and upper Midwest. In the East, New York, North Carolina, and Florida have sizeable indigenous populations. In the 2000 census, the Cherokee tribe was the largest with 729,533 members. The Navajo had the second largest population with 298,197 members. The next largest tribe was the Sioux with a population of 153,360. Although most of the Indian population reside off their reservations, about one third live on reservations (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000). Of 279 recognized reservations, only 18 had populations of 5000 or more in 2000. Reservations vary in size from almost 16 million acres of land on the Navajo Reservation to less than 100 acres on smaller reservations. Some reservations are occupied primarily by tribal members, whereas others are inhabited by a high percentage of non-Indian land owners (Bureau of Indian Affairs, 1991). The Mountain States (Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah) have the largest number of reservations in the United States. These reservations are relatively isolated and distant from urban centers. Given this remoteness, residents of these reservations intermarry less with non-Indians than do residents of other reservations—a fact reflected in the small share of American Indians reporting a multiracial heritage.

Multiethnicity and ganma

In today’s world, the lives of most indigenous peoples have been influenced by persons who have acted as colonizers. In recent years, it has been acknowledged that people frequently cannot be identified with one culture. Increasing numbers of interracial marriages and cross-cultural adoptions are resulting in multiethnic individuals and families (McCubbin et al., 2010). A great deal of diversity exists both within the American Indian and Alaska Native population and among the children of these groups. Some of these children live within a tightly knit circle of family, clan, and tribal members situated in remote reservations. Others live in cities distant from their family’s reservation and have only limited contact with their families or tribe. Some of this heterogeneity is manifest in the “mark all that apply” option for racial identification in the 2000 U.S. Census. About 2.5 million people were identified as nothing other than “American Indian” or “Alaska Native” in the 2000 U.S. Census. But another 1.6 million people were identified as American Indian or Alaska Native along with one or more other races, making a total of 4.1 million people who claim some connection with an American Indian or Alaska Native heritage. During recent years, many Native Americans have shifted from reservation to urban residences. Thus, exposure to the dominant culture and the associated adoption of dominant culture values varies widely.

To understand the cultural diversity of indigenous persons, one must recognize their multiethnicity. Indigenous lifestyles involve behaviors and beliefs regarding language, kin structure, religion, views of the land, and health (Red Horse, 1988). Each of these areas of beliefs and behaviors may be influenced in varying degrees related to the cultures encountered and whether the persons live on a reservation or ancestral lands versus an urban area. Some indigenous persons may maintain a traditional lifestyle in all aspects of their lives, whereas others may operate primarily within and identify with the dominant culture. In practice, many indigenous persons exhibit different cultures or different ethnicities or identities in different aspects of their lives.

Families with bicultural identities maintain some aspects of indigenous beliefs and behaviors, but have adopted much of the dominant culture’s lifestyle. Parents often understand the Native language but prefer to speak the language of the dominant culture. They do not teach the Native language to their children nor transmit traditional knowledge. Although they have acquired many characteristics of mainstream society, they are not totally socially integrated. They prefer relationships with other indigenous persons and often replicate traditional extended kin systems by incorporating nonkin friends into traditional roles. Their child-rearing practices are likely to reflect Indian values, although they may not be able to articulate these values explicitly (Miller & Schoenfield, 1975). They may attend powwows in urban areas or social dances in nearby reservations.

The Australian aboriginal concept of ganma provides a means for addressing the effects of multiple cultures coming together in a more positive way than the concept of acculturation. The ganma metaphor describes a situation in which water from the sea (Western knowledge) and a river of water from the land (Aboriginal knowledge) mutually engulf each other upon flowing into a common lagoon and becoming one (Pyrch & Castillo, 2001). In coming together, the streams of water mix across the two currents, and foam is created. The foam represents a new kind of knowledge. Essentially, ganma is the place where knowledge is created. One culture does not overwhelm another; rather a third culture arises at the point of intersection. Similarly, the collaboration of professionals from dominant cultures with indigenous parties results in unique services and training programs.

The ganma metaphor can serve as a foundation for clinical interactions in educational and health care systems. By employing the concept of ganma, one does not create marginalized groups that exist alongside a dominant culture, but rather one recognizes the primacy of all groups’ backgrounds and experiences. There is no one dominant culture enforcing a particular reality. If the two cultures (waters) can be kept in balance, in what Cazden (2000) called the “ganma space,” the nutrients that come together with the mix of waters nourish richly diverse forms of life.

Indigenous languages

Language loss

Every 14 days, a language dies. By 2100, more than half of the more than 7000 languages spoken on Earth—many of them not yet recorded—may disappear, taking with them a wealth of knowledge about history, culture, natural environment, and the human brain (http://www.nationalgeographic .com/mission/enduringvoices/.) In many cases, indigenous languages are spoken by relatively few persons and are not supported (and are even discouraged) by the dominant culture. As a result, indigenous languages are at high risk for being lost.

Indigenous languages vary greatly in the number of speakers, from Quechua, Aymara, Guarani, and Nahuatl (in Latin America) with millions of active speakers to a number of languages with only a handful of elderly speakers. Of the approximately 300 indigenous languages spoken in North America before the arrival of Columbus and the 250 spoken in Australia before the arrival of Europeans, more than half are extinct, and many are near extinction (Krauss, 1998; Walsh, 1991). In the United States, only about 20 languages are still spoken by people of all ages and are thus fully vital (Reyhner & Tennant, 1995). Some of these languages are spoken by only a few individuals, and others, such as Cherokee, Navajo, and Teton Sioux/Dakota, are spoken by thousands (Estes, 1999). The Navajo language is the most frequently spoken indigenous language in the United States, with 148,530 speakers.

Language defines a culture. Many endangered languages have rich oral cultures with stories, songs, and histories passed on to younger generations, but no written forms. Words that describe a particular cultural practice or idea may not translate precisely into another language. With the extinction of a language, an entire culture is lost. The National Geographic Society’s Enduring Voices Project (www.nationalgeographic.com/mission/enduringvoices/) and the Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages (www.livingtongues.org/) both seek to document and, when possible, to maintain or revitalize languages. By using appropriate written materials, video, still photography, audio recorders, and computers with language software, as well as access through the Internet where possible, these projects help empower communities to preserve ancient traditions with modern technology. The National Geographic Society has identified the most endangered language hotspots in the world—places where no children and few adults speak the indigenous language. Table 5-1 shows the eight most frequently spoken indigenous languages in the United States (www.aaanativearts.com/article592.html.)

TABLE 5-1 Most Frequently Spoken American Indian Languages

| Language | Locations | Speakers |

|---|---|---|

| Navajo | AZ, NM, UT | 148,530 |

| Cree | MT, Canada | 60,000 |

| Objiwa | MN, ND, MT, MI, Canada | 51,000 |

| Cherokee | OK, NC | 22,500 |

| Dakota | NE, ND, SD, MN, MT, Canada | 20,000 |

| Apache | NM, AZ, OK | 15,000 |

| Blackfoot | MT, Canada | 10,000 |

| Choctaw | OK, MS, LA | 9, 211 |

From www.cogsci.indiana.edu/farg/rehling/nativeAm/ling.html.

Indigenous groups in Hawaii, Australia, New Zealand, and North America have also experienced severe language loss. Latin America has large numbers of peoples who continue to speak indigenous languages. Mexico’s Mesoamerica region encompassed a large number of early civilizations, including the Olmec, Teotihuacan, Maya, and Aztec, before the arrival of Europeans. The region is now home to many of Mexico’s indigenous groups, which continue to speak ancestral languages despite cultural pressure to speak Spanish. The Andes Mountains of Peru and the Amazon Basin of Brazil have high language diversity, but there is little documentation of remaining indigenous languages. Spanish, Portuguese (in Brazil), and more dominant indigenous languages are replacing smaller ones. Speakers of small indigenous languages are shifting to Spanish or larger indigenous languages, such as Guaraní.

Language policy and revitalization

Since the 1960s, in Canada, indigenous languages have increasingly been taught in schools (Assembly of First Nations, 1990; Burnaby, 2008; Kirkness & Bowman, 1992). In addition, indigenous languages have been the medium of instruction up to the third grade in some schools in the territories and Quebec, where the children begin school speaking only or mainly their indigenous language. Indigenous language immersion programs have begun in several communities, where the children start school speaking only or mainly an official language (English or French). Nine indigenous languages have been made official languages in the Northwest Territories together with English and French. The new territory of Nunavut has declared Inuktitut, Inuinaqtun, French, and English as official languages and is actively developing policies for extensive use of these languages in many domains.

The latter 20th century has witnessed indigenous language revival efforts in Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii, North America, and the circumpolar north (Cantoni, 2008; King, 2009; Reyhner & Lockard, 2009). In the 21st century, indigenous communities around the globe have been using modern technology to help maintain and even revitalize their threatened and dying languages and cultures (De Korne, 2009). Thousands of tribal communities, from the circum- polar north to the outback of Australia to the forests of the Northwest Pacific Coast, are creating educational programs to record the stories and oral traditions of their elderly last speakers. Using cameras, film, and audio, community members are creating powerful archives of material as well as elaborate word dictionaries. By fall 2011, 20 episodes of the Berenstain Bears animated cartoon series will be broadcast on South Dakota Public Television, with all dialogue dubbed in Lakota. A DVD will be released as well, complete with a Teachers’ Guide. This Lakota Language Consortium project was initiated last year as part of its mission to promote the language outside of the schools (www.lakhota.org/html/BBprojectstart.html.)

Passing the knowledge along to the younger generation has become of paramount importance and urgency. Without younger generations speaking and understanding the words and stories of their ancestors, the language dies. And when the language dies, the culture dies. Fishman (2000) observed that successful language revitalization initiatives in many parts of the world are not just about reversing language loss. Rather, they are “about adhering to a notion of a complete, not necessarily unchanging, self-defining way of life” (p. 14). An indigenous language is a link to the past, that is, to the ancestors and a traditional way of life. If the language is lost, many of the cultural practices and events no longer have meaning. It is through language that one is able to participate fully in cultural events. Without language, traditions such as hunts, songs, and dances would lose their significance because embedded in the songs and stories are values such as cooperation, kinship, respect (e.g., for self, mother earth, animals), and responsibility. The sense of place, belonging, identity, and values are expressed through language. The implications and consequences of attitudes toward language and its preservation and the resources available for language preservation and maintenance efforts are complex issues and affect progress across and within communities.

Indigenous english

In some indigenous groups, characteristics of the indigenous language have been transferred to the dominant language spoken in an area. The influences of indigenous languages on English have been documented for American Indians (Leap, 1993), Canadian First Nations (Ball & Bernhardt, 2008), Australian Aborigines (Butcher, 2008), and Maori (Bell, 2000; Holmes, 1997). There are several ways that indigenous languages influence English. Some of these influences include (1) retention of the phonemic and phonological characteristics of the indigenous language, (2) indigenous language syntactic rules taking priority over English syntactic rules, (3) word formation and grammar markings from the indigenous language influencing the English dialect, and (4) constructions found in other nonstandard variations of English also being found in indigenous English. Even when there has been no contact with the indigenous language for many generations, the indigenous language may strongly influence the present English dialect. For example, Wolfram (2000) has described and traced the roots of the Lumbee Indians in North Carolina. Although the Lumbee are not a recognized tribe, they are ethnically and culturally Native American. The Lumbee lost their language many generations ago. The Lumbee dialect shows the influence of early colonization by the English, Scots, and Scots-Irish, but Lumbee speech is distinctly different from its Anglo-American and African American neighbors. For example, Lumbee speakers may use the finite bes (e.g., “I hope it bes a little girl”; “It bes really crowded”; “The train bes running”) and the perfective I’m (e.g., “I’m went down there”). African American and European American natives do not use these patterns, even when they grow up practically next door to the Lumbees who do (Dannenberg & Wolfram, 1998).

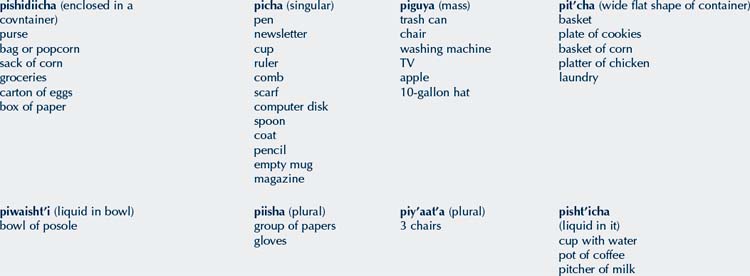

These Southwest Indian languages have an SOV (subject-object-verb) sentence structure. Verbs are highly inflected. There are no gender pronouns or pronouns for “it.” As a consequence, both children and adults may use gender pronouns incorrectly when speaking English. Pronominal prefixes on verbs code the relationships of subjects and objects to the verbs (possessor, agent, patient, benefactee) and person (first, second, third, fourth [passive]). Number is coded in the verb as one, two, and more than two. Location (coded by prepositions in English) is coded in the verb and is influenced by the characteristics of the objects (see example in Box 5-1). Size comparisons are made on the basis of volume and plane in space (vertical or horizontal). Hence, there are no generic words for big and little. As a consequence, preschool children may be confused when confronted by tasks of classifying objects as “big” or “little.” One cannot use the same word to talk about a “big snake” and a “big elephant.”

Valiquette (1990) noted that in Keres (spoken in five Pueblo groups), infinitives are rare, and dependent clauses (which in English use connective words such as when, while, until, because, before, after, although, if) are used but appear to be related to age privilege differences, not to age developmental differences. That is, as one matures and gains stature in the community, one uses dependent clauses with increasing frequency and a wider variety of purposes. A form of “and” is used as the connective in many dependent clauses. Valiquette (1990) suggested that this is the result of the frequent use of “and” (“y”) in English and Spanish. It may, however, also be a reflection of how Native Americans perceive the temporal and causal relationships coded in dependent clauses (Hall, 1983). Time is not viewed as linear, and cause goes beyond physical principles (Cajete, 2000).

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) must be alert to the varieties of indigenous English and how they may affect children’s performance on speech-language tests. Silver and Miller (1997) have documented the basics of grammar in 160 Native languages, along with discourse genres (language functions) and relationships between language and worldview. Mithun (2001) provides information on the sound, syllable, and syntactic patterns of all the indigenous languages of North America. In addition, she provides some discussion of “baby talk,” narrative, and ceremonial language use by some of the indigenous groups. Dixon (2007) provides linguistic descriptions of Australian Aboriginal languages, and Harlow (2007) provides this for Maori. An understanding of the characteristics of the indigenous language can enable SLPs to identify the characteristics of indigenous-influenced English in particular groups.

Worldviews and cultural values

A worldview is a way of seeing the world. The worldviews of indigenous cultures contrast with worldviews of dominant cultures. Although there is considerable variation in values and beliefs among indigenous cultures, there are some similarities in their worldviews (Hart, 2010). Knudtson and Suzuki (1992) described the indigenous worldview as reflected in the stories and traditions from 22 different indigenous cultures around the world. They contrast the indigenous mind with the scientific mind. The worldviews of indigenous peoples have a spiritual orientation that is embedded in all elements of the world and cosmos. Indigenous peoples believe that humans live in harmony with the world. The resources of nature are viewed as gifts; and nature is honored through spiritual practices. Time is measured by the daily, monthly, and yearly cycles of nature. In contrast, dominant cultures typically view time as linear and document it in terms of a chronology of human activities.

To interpret assessment data and provide appropriate and acceptable interventions for indigenous peoples, clinicians must have an understanding not only of the ways of knowing of the group but also of the cultural values and beliefs that underlie their ways of knowing. A variety of approaches have been used to study cultural variations in values and beliefs among people (Hall, 1976; Hofstede, 1980; Kluckhohn & Strodtbeck, 1961; Triandis, 1995). Cultures can differ along several dimensions. Although there is considerable variation among indigenous cultures, there are some ways in which indigenous cultures are more similar to one another than they are to dominant cultures.

Individualism versus collectivism

All societies must strike a balance between independence and interdependence—between individuals and the group (Greenfield, 1994). Dominant cultures of northern European heritage are strongly individualistic, whereas indigenous groups are generally collective. Individualistic cultures emphasize the individual’s goals, whereas collectivistic cultures stress that group goals have precedence over the individual’s goals. In individualistic cultures, people look after themselves and their immediate family only, whereas in collectivistic cultures, people look after members of their in-groups or collectives in exchange for loyalty (Triandis, 1995). Collectivistic cultures emphasize goals, needs, and views of the in-group over those of the individual; the social norms of the in-group, rather than individual pleasure; shared in-group beliefs, rather than unique individual beliefs; and a value on cooperation with in-group members, rather than maximizing individual outcomes. Perhaps a better term in indigenous cultures is “relatedness” (Martin, 2008). There is a depth of relatedness among all people within the group. In some indigenous cultures, relatedness is reflected by persons introducing themselves by first identifying the clans or extended families to which they belong rather than by their given names. In a YouTube video Terry Teller, a Navajo, introduces himself: “I’m from the Water Flows Together Clan (mother’s clan). I’m from the Coyote Pass People (father’s clan). My maternal grandparents are from the Sleeping Rock Clan. My paternal grandparents are from the One Who Walks Around Clan” (www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZbZBX2lgWUg0.) Aunts and uncles may be referred to as mother and father and cousins as brother and sister.

The collectivist nature of the indigenous cultures can influence assessment and intervention. Children in a collective culture are more likely to provide assistance to others, even in ways that mainstream teachers consider cheating. Although indigenous communities function collectively in terms of having responsibilities for one another, there is also respect for individuality. Everyone is viewed as fulfilling a purpose, and as a consequence, no one has power to impose values on others. Autonomy is highly valued, and children are expected to make their own decisions and operate semi-independently at an early age. They may be left alone to tend sheep or watch younger siblings at young ages. Children are allowed choices and freedom to experience the natural consequences of their choices. Despite the children’s freedom to make choices, the impact of their choices on others is also emphasized (LaFromboise & Low, 1989). Mainstream service providers have sometimes misinterpreted this early independence as an indication of neglectful or uninvolved parents.

Doing versus being or being-in-becoming

Cultures of northern European heritage epitomize the doing orientation in which there is “a demand for the kind of activity that results in accomplishments that are measurable by standards conceived to be external to the acting individual” (Kluckholn & Strodtbeck, 1961, p. 17). Persons seek to be in control, to be in charge. In contrast, indigenous cultures represent being and being-in-becoming cultures. The being orientation is concerned with who one is, not what one can do or has accomplished. One is valued simply for being. One’s worth is not decreased if one has a disability or as one ages and becomes less physically able. The focus on human activity in the being-in-becoming orientation is on striving for an integrated whole in the development of self. Therefore, there is no need to compete and prove one better than others. As a result, indigenous children do not need to strive to be better or to stand out from others. A number of researchers, in fact, report that indigenous children may actively avoid being singled out even to be praised for good performance. Praise in front of a group may bring a sense of shame (Boggs, 1985, Hawaiian; Eriks-Brophy & Crago, 2003, Inuit; Deyhle, 1987, Navajo; Gould, 2008a, Australian Aboriginal).

Relationship to nature

Indigenous peoples, in contrast, maintain a harmony-with-nature orientation that makes no distinction between or among human life, nature, and the supernatural. With their being-in-becoming and harmony with nature orientations, indigenous peoples tend to have a greater tolerance for variation, and they may feel less need to “fix things,” focusing instead on learning how to accept and cope with their circumstances. Families may recognize that a family member is different but accept that difference as being who the person is. Because of such viewpoints and values, they may be less likely to seek out evaluation and treatment services. When they do become involved, it is important to include the extended family in decisions. According to Benally (1989), Navajo education focuses on preparing individuals to reach a state of hozho—a state achieved through a balanced and harmonious life. All knowledge is viewed with respect to its ability to draw one closer to this spirit of harmony. Traditionally, individuals are taught the interrelationship and interdependence of all things and how they must harmonize with them to maintain balance and harmony.

Time orientation

Orientation to human activity influences perceptions and use of time. Mainstream cultures are driven by “clock time,” whereas indigenous cultures are more attuned to “event time” (Harris, 1998). Hall (1976) refers to these two orientations toward time as monochronic and polychronic. Monochronic time emphasizes schedules, segmentation, and promptness. With the exception of birth and death, all important activities are scheduled. Polychronic time systems are characterized by several things happening at once. They stress involvement of people and completion of transactions rather than adherence to present schedules. Nothing seems firm; changes in the important events occur right up to the last minute, creating frustration for those who may value promptness and sticking to well-organized plans and schedules. Indigenous peoples believe in the cyclical nature of time—days, months (in terms of moons), and years (in terms of seasons or winters). Many cultures developed elaborate ways to track time. For example, the Anasazi, ancestors of the present Southwest Pueblo Indian groups, were highly attuned to time. At Fajado Butte in New Mexico, they arranged boulders and carvings in the rock mesa that mark the sun’s solstices and equinoxes and the 11-year cycle of the moon (Sofaer, 2007; Sofaer & Ihde, 1983). The “sun dagger” of Fajado Butte is considered the Stonehenge of the New World.

Scollon and Scollon (1980) reported that Athabaskan Indians believe it is inappropriate to speak of plans or to anticipate the future. Navajos believe that one should live a long life and not limit one’s potential with a specific plan or timeline. They believe that if one sets a specific plan for future actions, one may limit all other possibilities for living a long life (Mike et al., 1989). Although Native Americans may not be consciously aware of the reasons for not planning, they may have grown up in environments where planning ahead was not done and time was not rigidly scheduled. Activities are done “when the time is right.” Although one may be told that a dance or a chapter house meeting may begin at a particular time, this may only mean that the event will occur in the near future. The actual event may not begin for several hours. The idea of what constitutes “being late,” then, differs in mainstream and Indian cultures. Children growing up in polychronic time systems are less likely to have experienced the pressure to perform quickly, and as a consequence, they may not perform well on timed tests.

Mainstream cultures value schedules and punctuality. Actions focus on the immediate and the future. Activities are bound to the imposed rhythms of work days, time clocks, overtime, saving time, and taking time out. “The ticking of the clock is more important than the beat of the human heart” (Bruchac, 1994, p. 11). Mainstream service providers sometimes think that indigenous clients have no sense of time because they may not honor imposed schedules (Hall, 1983).

Communication patterns

Conversation

Frequent miscommunication arises when indigenous persons and dominant-culture persons interact because their values and beliefs affect their styles of communication. Australia has produced a document, Aboriginal English in the Courts, to explain the confusions that can occur when examining Aboriginals in the court system (Eades, 2000). Eades noted that long periods of silence are generally avoided in mainstream discourse except among intimate friends or relatives. In Aboriginal societies, on the other hand, lengthy periods of silence are the norm and are expected during conversation, particularly during information sharing or information seeking. Persons in the dominant culture may interpret a person’s silence or lack of overt acknowledgment during questioning as unwillingness to participate or answer. Greater tolerance of silence in conversation has been reported for a number of indigenous groups, including Australian Aborigine (Mushin & Gardner, 2009), Apache (Basso, 1990), Navajo (Plank, 1994), Salish (Covarrubias, 2007), and Inuit (Crago, 1990).

Scollon and Scollon (1980) suggested that problems arise between mainstream speakers and Alaskan Athabaskan natives in three areas: (1) speakers’ presentations of themselves, (2) organization of talk, and (3) contents of talk. Table 5-2 summarizes communication differences between persons from northern European heritage backgrounds and indigenous speakers that have been identified by a number of anthropologists and educators study ing indigenous persons in North America (Basso, 1990; Hall, 1959; 1976; 1983; Philips, 1983; Saville-Troike, 1989; Scollon & Scollon, 1980).

TABLE 5-2 Cross-Cultural Perspectives of Speakers

| Mainstream Perspective of Native American Speakers | Native American Perspective of Mainstream Speakers |

|---|---|

| Presentation of Self | |

| Distribution of Talk | |

| Contents of Talk | |

Source: Reprinted with permission from Scollon R., & Scollon, S. B. (1980). Interethnic communication. Fairbanks, AK: Alaska Native Language Center.

Mainstream persons get to know others by talking; only when they know someone well do they think there is less need to talk. In contrast, many indigenous people prefer talking to those they know well; when they do not know someone well, or in cases in which people have been separated for some time, they prefer to watch and listen until they have gathered sufficient information about a person. Basso (1990) tells the story of Native American parents waiting at the trading post for their children to arrive home from boarding school where they have been for several months. The children got off the bus and piled into their parents’ trucks. Unlike mainstream families, in which parents would question children about their activities over the past months, the Native children and parents spoke minimally. When Basso questioned parents about this, they reported, “We know that our children have been to the Whiteman’s school. When they return to us, we do not know who they are. We must watch and listen until we know who they are.”

The nature of communication that occurs in classrooms employing a Western education system may be unfamiliar, confusing, or threatening to indigenous children. The person in the dominant position (the teacher or clinician) asks questions and then listens to persons in the subordinate position (students) to show what they know. Mainstream children are expected to perform even if they are not sure or make a mistake. In contrast, indigenous children are expected to learn by watching, and they do not perform until they have mastered the skill. When teachers ask indigenous children to display knowledge, the children may be silent or may appear to become unruly. To the children, teachers may appear incompetent because they are not doing most of the talking, yet they are acting superior (Scollon & Scollon, 1980).

Hall (1959; 1976; 1983) differentiated cultures on the basis of the communication style that predominates in the culture. A high-context communication or message is one in which “most of the information is either in the physical context or internalized in the person, while very little is in the coded, explicit, transmitted part of the message.” A low-context communication or message, in contrast, is one in which “the mass of the information is vested in the explicit code” (Hall, 1976, p. 79). Although no culture exists at either end of the low- to high-context continuum, the cultures of mainstream Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States are placed toward the lower end; indigenous cultures fall toward the high-context end of the continuum. When persons from high-context cultures communicate with persons from low-context cultures, they are likely to experience miscommunication. The indirect, nonspecific style of high-context indigenous individuals appears vague to low-context mainstream individuals, and they are likely to suspect that the high-context individual is being intentionally evasive or uncooperative. The loud, explicit, direct style of low-context mainstream individuals appears impolite, rude, and disrespectful to high-context indigenous peoples.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree