OBJECTIVES

Objectives

Define cross-cultural communication.

Review evidence for the need to improve cross-cultural communication.

Describe challenges to effective cross-cultural communication and how they have an impact on clinical care.

Describe strategies for effective cross-cultural communication.

Ms. Jones is a 56-year-old African-American classroom assistant who was hospitalized with a stroke. Her course rapidly deteriorated and her physicians determined that aggressive treatment would be futile. They approached her family with the recommendation that life support be removed. The doctors explained that Ms. Jones had multiorgan failure and little hope of recovery. Her family, a daughter and two sisters, were shocked by this recommendation and accused the physicians, all of whom were white, of substandard care.

INTRODUCTION

When patients and physicians interact, cross-cultural communication is a common occurrence as patients and clinicians differ in many important ways. Patients from vulnerable populations (including persons from racial and ethnic minority populations, immigrants, low-income persons, and persons with low educational attainment) and health-care providers face unique challenges to effective communication. These challenges are borne of the differences in life experiences, cultural norms, assumptions, expectations, and barriers inherent in a health-care system in which the biomedical model of health predominates. While this chapter takes an example of an African-American family interacting within the US health-care system, cross-cultural communication is observed in every country, and, to a certain extent, in every clinical encounter. Patients and physicians may share a common background and have similar expectations of the clinical encounter, yet still differ radically in their level of knowledge or in their personal values. Navigating cross-cultural communication is the norm in most medical encounters.

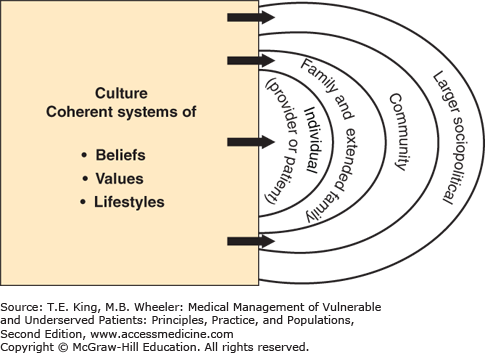

Culture is a coherent system of beliefs, values, and lifestyles held by individuals, their communities, and the larger sociopolitical structure in which they live. Culture is a dynamic entity and is responsive to changes such as socioeconomic position, immigration, and other factors (Figure 14-1).

Figure 14-1.

Culture is a coherent system of beliefs, values, and lifestyles. Individuals’ culture is influenced not only by their personal circumstances but also of their families and extended families’ cultures, the culture of their communities, and the culture of the larger social political environment. Individuals, families, communities, and societal cultural systems are dynamic and responsive to multiple forces such as socioeconomic conditions.

Cross-cultural communication in the context of health care is both complicated and complex because of these multiple determinants of culture and the inherent complexities of medical care. Effective cross-cultural communication acknowledges the interplay of multiple factors, including race, ethnicity, cultural norms, religion, socioeconomic position, and education to achieve a common understanding or aim. Effective cross-cultural clinical communication also results in sharing of key information and demonstration of caring. This chapter discusses common barriers to effective cross-cultural communication and how to overcome them. (For a discussion of the effective use of interpreters, see Chapter 31).

EXTENT OF THE PROBLEM

There is abundant evidence that patients are concerned about the lack of effective communication with their physicians and other health-care providers. Patients perceive communication problems with their physicians regardless of background—including English-speaking, white, educated patients. That said, communication problems are more common for minority patients and for patients with limited English proficiency. The Commonwealth Fund reported results of a national survey in which 39% of Latinos, 27% of Asian Americans, 23% of African Americans, and 16% of whites reported problems with communication, specifically that their doctor did not listen to everything they had to say, they were not able to understand their doctors, and they were not able to ask questions during their visits.1 Similar reports of poor doctor–patient communication exist in surveys of patients across many different countries with very different health-care systems.2,3

Physicians give more information and offer more support and encouragement to patients who ask questions and express concerns. Creating an obvious feedback loop, patients ask more questions when physicians engage in partnership-building behaviors, but physicians engage in more partnership-building behaviors when the patient is more educated.3,4,5 Latinos and Asian Americans commonly report that physicians do not adequately involve them in decision making.6,7 African Americans are also less likely than whites to report that their doctors include them in decision making, especially when the patient and doctor are of different races.8 Physicians tend to be more verbally dominant and engage in less patient-centered communication with African-American patients than with white patients, less likely to explain test results, medical conditions, and treatments.9

Ineffective cross-cultural communication is of particular concern in the management of chronic diseases, in high stakes decision making in acute care, and in the context of end-of-life care. African Americans report that they would like to discuss preferences for resuscitation in the event of a cardiopulmonary arrest, but they are more likely than whites not to have done so.10 African Americans are more likely to want family members to make decisions for them at the end of life compared with others, but believe that physicians would not involve families in collaborative decision making.11,12

Despite the recent attention to cultural competence in medical school curricula, several studies document persistent deficits in cross-cultural communication among medical students and physicians.13

CHALLENGES IN CROSS-CULTURAL COMMUNICATION

Ms. Jones’ family does not care that the medical evidence suggests that further treatment is futile. Their life experience has taught them that life is precious, withstanding suffering is a sign of faith, and that African Americans have often beaten the odds and defied death. They do not completely trust the health-care system to do the best for Ms. Jones.

Multiple barriers at the patient, provider, and health system levels contribute to the communication difficulties in this scenario. Clear disagreement has arisen between Ms. Jones’ family and her medical team about appropriate care. Interactions between the family and the health-care providers are strained. The health-care providers do not understand the family’s reaction; they believe the family does not understand the limits of medical technology in this clinical situation. The family believes the physicians are acting out of prejudice or bias and are not offering Ms. Jones the same care she would receive were she white or young. The physicians did not involve the family in their decision making, but simply presented them with their recommendation about withdrawing life support. They have failed to consider potential differences that may have led to this communication breakdown, including racial discordance between the treatment team and the Jones family, religion, spirituality, and the relevant broader social context.

In some cultures, it is considered inappropriate for patients to ask questions of the health-care provider.14 In dominant US culture, patients with lower socioeconomic status or low health literacy are often intimidated in the clinical interaction and do not solicit additional information or express their wishes.3 Researchers have demonstrated that patients can learn assertiveness skills that result in more participatory clinical interactions.15

The Ask Me Three campaign (http://www.npsf.org/?page=askme3) is an example of a large-scale patient education campaign aimed at activating patients to ask more questions. Health coaches, who meet with the patient before the clinical interaction, can be very helpful in empowering patients to ask questions and express their own values. For issues as diverse as pain control in cancer patients in the United States16 to reproductive care in poor Indonesian women,17 coaches or navigators can play a key role in improving patient–doctor communication.

Lack of trust of the health-care provider may be a significant barrier to effective communication. One strategy that some patients may use to protect against stereotyping by clinicians is to withhold information that they perceive would be viewed negatively. Trust is particularly relevant for groups that have historically experienced bias in the health-care system, as reflected in denial of service, segregated service, or blatantly inferior service.18 The legacy of past abuses such as the US Public Health Service Syphilis Experiment continues to influence some African Americans’ ability to trust the system.19 In 2010, revelation about a related Guatemala syphilis experiment has caused widespread distress among Latinos.20

Health-care clinicians often overestimate patient understanding of key concepts in care, including prevention, self-management, and chronic disease processes. This can result in significant discordance in visit goals and expectations. It is important for providers to develop skills that permit them to ascertain the extent of patients’ understanding of their clinical condition, and to work with them to establish appropriate, mutually acceptable goals and strategies for addressing clinical concerns (see Chapter 15).

Clinician deficiencies are the most frequently described contributors to poor cross-cultural communication, likely because they have been the most thoroughly researched. Physicians are less satisfied with their interactions with patients who are racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse. They perceive that patients from these groups are less interested in prevention, managing their illnesses, and engaging in healthy behaviors.21,22

Frustration may stem from the clinicians’ lack of awareness regarding the influence of their own cultural norms. Clinicians are often unaware that they reveal negative attitudes to patients, particularly when addressing the health beliefs and behaviors of unfamiliar cultures. Physicians and patients often do not discuss the “cultural rules” that underlie their interactions until there is a problem. Perhaps, most importantly, physician attitudes and lack of communication skills can lead to decreased patient trust.23

Stereotyping is a particularly important challenge when caring for vulnerable patients. Clinicians often wish to learn about the specific health beliefs of distinct cultural groups, which can be quite helpful. However, knowledge about general cultural beliefs in specific populations is insufficient for effective cross-cultural communication. Persons from racial and ethnic minority groups represent a wide range of cultures, beliefs, and attitudes depending on place of birth, educational attainment, socioeconomic position, acculturation, and other factors. So, knowledge of general health beliefs and attitudes of a group of people can be used only to generate hypotheses that can be tested with individual patients.

The unconscious (and certainly the conscious) use of appearance or some other personal characteristic to stereotype patients is a routine occurrence. The 2003 Institute of Medicine report, Unequal Treatment, documented a long list of studies documenting bias in diverse clinical fields from cardiac care to HIV/AIDS diagnosis and treatment, and the treatment of pain.24 In another example of stereotyping, studies have shown African Americans were judged more likely to be substance abusers and were rated as less intelligent and less educated when compared to whites.25

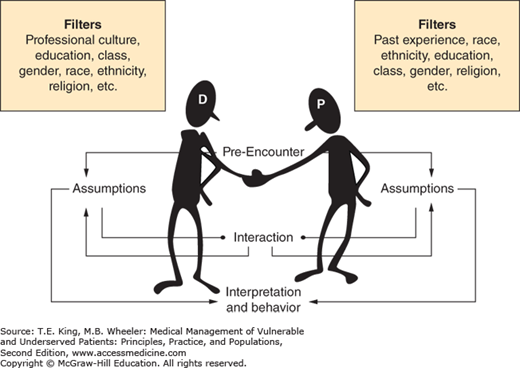

Patients and clinicians each enter interactions with assumptions about the other party, and cultural factors influence their predetermined expectations about how the encounter will proceed (Figure 14-2).17 Clinicians need to be conscious of how these assumptions are developed and then negotiate expectations and goals based on input from the individual patient (Box 14-1).

Figure 14-2.

Both the doctor (D) and patient (P) use filters that influence assumptions made about each other and each understanding of the interaction. These assumptions influence the interpretation of what happened in the interaction and subsequent behavior. When the doctor and/or patient are aware of how they use their filters, they may reexamine their assumptions and thus influence the interaction and interpretation of the interaction.

Box 14-1. Common Pitfalls

Failing to appreciate cultural differences, rendering one’s own values dominant, and dismissing the value systems held by others

Making the medical model the only or dominant paradigm

Stereotyping groups as a shortcut to understanding whether and how the individual patient values cultural norms

Bias and lack of personal awareness of bias

Using medical jargon and technical language that impede communication

Failing to check for meaning and understanding with the patient

Failing to inquire about patient preferences for decision making

Failing to express empathy in cross-cultural communication clinical encounters

Failing to express empathy in communication mediated via an interpreter

Lack of awareness of historical events that may shape patient illness and beliefs

Historically, health-care professionals have received little or no training in cross-cultural communication. In addition, many system-level forces obstruct improvements in effective communication (Box 14-2). Furthermore, the physical limitations of clinical sites often do not facilitate the unique decision-making styles of some groups. In cultures in which family decision making is valued above individual one-on-one interactions, examination rooms may be too small, yet conference rooms to hold family meetings are frequently nonexistent, and the hours of operation often do not accommodate work and care-taking schedules of extended families.

Box 14-2. Systems-Level Challenges to Effective Cross-Cultural Communication

Growing diversity of the US population without concurrent diversification of health-care professional staffs

Increasing emphasis on technology and use of electronic medical records, which may undermine and underemphasize the need to talk to patients face to face

Pressure on health-care clinicians to care for more and sicker patients in shorter clinical encounters

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree