Nerve and pain disorders

With nerve and pain disorders, damage that causes impairment is the focus of the patient’s problem and may cause significant distress or dysfunction. Nerve disorders include Bell’s palsy, extraocular motor nerve palsies, peripheral neuritis, and trigeminal neuralgia. Pain disorders include complex regional pain syndrome.

NERVE DISORDERS

BELL’S PALSY

With Bell’s palsy, impulses from the seventh cranial nerve— the nerve responsible for motor innervation of the facial muscles—are blocked.

Although the exact cause of Bell’s palsy is unknown, possible causes include ischemia, viral disease such as herpes simplex or herpes zoster, local traumatic injury, or autoimmune disease.

Bell’s palsy can affect all age-groups; however, it occurs most commonly in people ages 20 to 60. Onset is rapid. In 80% to 90% of patients, the disorder subsides spontaneously, with complete recovery in 1 to 8 weeks. If recovery is partial, contractures may develop on the paralyzed side of the face. The disorder may recur on the same or the opposite side of the face.

Pathophysiology

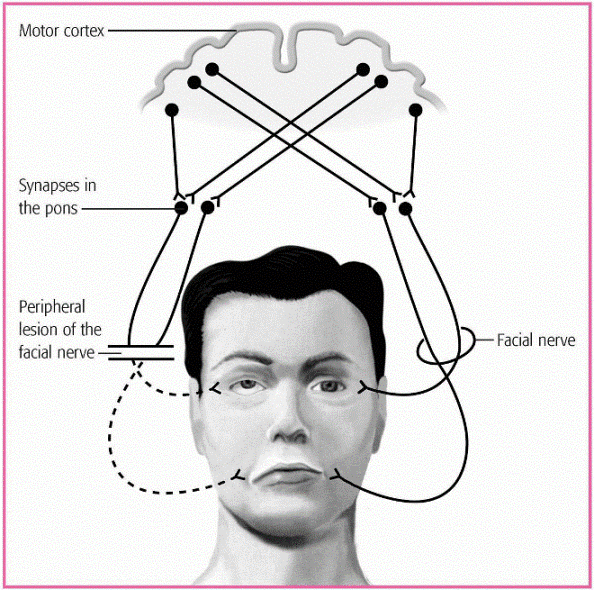

Bell’s palsy reflects an inflammatory reaction around the seventh cranial nerve, usually at the internal auditory meatus where the nerve leaves bony tissue. This inflammatory reaction produces a conduction block that inhibits appropriate neural stimulation to the muscle by the motor fibers of the facial nerve, resulting in the characteristic unilateral or bilateral facial weakness. (See Neurologic dysfunction in Bell’s palsy.)

Complications

Corneal ulceration

Blindness

Impaired nutrition

Psychosocial problems

Assessment findings

Pain on the affected side

Difficulty eating on the affected side

Difficulty speaking clearly

Drooping mouth and drooling

Distorted taste perception over the affected anterior portion of the tongue

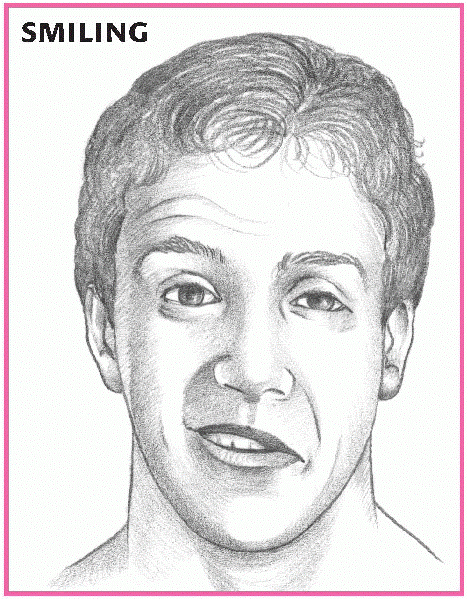

Inability to raise the eyebrow, smile, show teeth, or puff out the cheek on the affected side

Difficulty closing the eye on the affected side; if attempted, the eye rolls upward (Bell’s phenomenon) and shows excessive tearing (see Facial paralysis in Bell’s palsy)

Diagnostic test results

Diagnosis is based on clinical presentation.

Electromyography helps predict the level of expected recovery by distinguishing temporary conduction defects from a pathologic interruption of nerve fibers.

Treatment

Appropriate treatment consists of administration of corticosteroids to reduce facial nerve edema and improve nerve conduction and blood flow. Corticosteroid therapy is especially helpful when started within a week of the symptom’s onset. After 2 weeks of corticosteroid therapy, electrotherapy may help prevent facial muscle atrophy.

Analgesics help to control facial pain and discomfort. Moist heat applied to the affected side may also provide some comfort. Lubricants or an eye ointment may be needed to protect the eye; patching during sleep may also be necessary.

If the patient fails to recover from facial paralysis, surgery that involves exploration of the facial nerve may be necessary.

Nursing interventions

Provide psychological support to the patient. Reassure him that he hasn’t had a stroke. Tell him that spontaneous recovery usually occurs within 8 weeks. This should help decrease his anxiety and help him adjust to the temporary change in his body image.

Administer medications and monitor for adverse reactions.

Monitor serum glucose levels during corticosteroid therapy.

Apply moist heat to the affected side of the face, as ordered.

Massage the patient’s face with a gentle upward motion two to three times daily for 5 to 10 minutes; teach massage to the patient.

Apply a facial sling, if necessary, to improve lip alignment.

Provide frequent and complete mouth care, taking special care to remove residual food that collects between the cheeks and gums.

DISCHARGE TEACHING

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH BELL’S PALSY

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH BELL’S PALSYBefore discharge, be sure to cover with the patient and his family:

the disorder and its implications

medication administration, dosage, and possible adverse effects, and when to notify the physician

about protecting his affected eye by covering it with an eye patch, especially when outdoors

facial exercises

the importance of maintaining good nutrition

signs and symptoms of complications

the importance of follow-up care

the benefit of utilizing available community support groups such as the local chapter of the Bell’s Palsy Research Foundation.

Provide a soft, nutritionally balanced diet, eliminating hot foods and fluids.

Provide preoperative and postoperative care, as appropriate.

Provide appropriate education to the patient and his family before discharge. (See Teaching the patient with Bell’s palsy.)

EXTRAOCULAR MOTOR NERVE PALSIES

In patients with extraocular motor nerve palsies, dysfunction affects cranial nerves (CNs) III, IV, and VI. These nerves are responsible for innervating eye movements. The most common causes of extraocular motor nerve palsies include diabetic neuropathy, trauma, and pressure from an aneurysm or a brain tumor. Other causes vary depending on the cranial nerve involved. (See Causes of extraocular motor nerve palsies, page 318.)

Pathophysiology

Nerve palsies occur with inflammation of the nerve and affect their function. The extraocular nerves perform several functions.

The superior branch of the oculomotor nerve (CN III) innervates the levator superior muscle of the upper eyelid and the superior rectus muscle of the eye; the inferior branch innervates the interior rectus, medial rectus, and inferior oblique muscles. It also supplies the intrinsic pupillary and ciliary muscles, which control lens shape and accommodation. The trochlear nerve (CN IV) innervates the superior oblique muscles, which control downward rotation, intorsion, and abduction of the eye. The abducens nerve (CN VI) innervates the lateral rectus muscles, which control inward movement of the eye.

The superior branch of the oculomotor nerve (CN III) innervates the levator superior muscle of the upper eyelid and the superior rectus muscle of the eye; the inferior branch innervates the interior rectus, medial rectus, and inferior oblique muscles. It also supplies the intrinsic pupillary and ciliary muscles, which control lens shape and accommodation. The trochlear nerve (CN IV) innervates the superior oblique muscles, which control downward rotation, intorsion, and abduction of the eye. The abducens nerve (CN VI) innervates the lateral rectus muscles, which control inward movement of the eye.

CAUSES OF EXTRAOCULAR MOTOR NERVE PALSIES

Causes of extraocular nerve palsies may include the following:

Oculomotor (cranial nerve [CN] III) palsy or acute ophthalmoplegia, may result from brain stem ischemia or other cerebrovascular disorders, poisoning (lead, carbon monoxide, botulism), alcohol abuse, infections (measles, encephalitis), trauma to the extraocular muscles, myasthenia gravis, or tumors in the cavernous sinus area.

Trochlear (CN IV) palsy may result from closed head trauma (for example, a blow-out fracture) or sinus surgery.

Abducens (CN VI) palsy may result from increased intracranial pressure, brain abscess, stroke, meningitis, arterial brain occlusions, infections of the petrous bone (rare), lateral sinus thrombosis, myasthenia gravis, and thyrotropic exophthalmos.

Complications

Diplopia

Ptosis

Strabismus

Nystagmus

Ocular torticollis

Assessment findings

Recent onset of diplopia (varies in different fields of gaze based on the eye muscles affected)

Torticollis (from repeatedly turning the head to compensate for visual field defects)

With CN III palsy:

Ptosis

Extropia (eye positioned outward)

Pupillary dilation and unresponsiveness to light and accommodation

Inability to move the eye

With CN IV palsy:

Inability to move the eye downward or upward

With CN VI palsy:

Estropia (inward deviation of the eye)

Diagnostic test results

Diagnosis is based on neuro-ophthalmologic examination.

Blood studies may detect diabetes.

Computed tomography scanning, magnetic resonance imaging, or skull X-rays may be done to rule out intracranial tumors.

Angiography may be done to evaluate possible vascular abnormalities.

Culture and sensitivity tests may rule out infection.

Treatment

Appropriate treatment varies depending on the cause. For example, neurosurgery may be necessary for a brain tumor or an aneurysm. For infection, massive doses of antibiotics may be appropriate. After treating the primary condition, the patient may need to perform exercises that stretch the neck muscles to correct acquired torticollis (wry neck). Other care and treatments depend on residual symptoms.

DISCHARGE TEACHING

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH EXTRAOCULAR MOTOR NERVE PALSIES

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH EXTRAOCULAR MOTOR NERVE PALSIESBefore discharge, be sure to cover with the patient:

the disorder and its implications

medication administration, dosage, and possible adverse effects, and when to notify the physician

exercises to improve neck movement

signs and symptoms of complications

the importance of follow-up care

the benefit of utilizing available community support groups.

Nursing interventions

Provide emotional support to help minimize the patient’s anxiety about the cause of the motor nerve palsy.

Provide treatment appropriate for the specific cause of the palsy.

Encourage neck exercises if torticollis is present.

Provide appropriate education to the patient before discharge. (See Teaching the patient with extraocular motor nerve palsies.)

PERIPHERAL NEURITIS

Peripheral neuritis, also called multiple neuritis, peripheral neuropathy, and polyneuritis, is the inflammatory degeneration of peripheral nerves that primarily supply the distal muscles of the extremities. It results in muscle weakness with sensory loss and atrophy and decreased or absent deep tendon reflexes. Because onset is usually insidious, patients may compensate by overusing unaffected muscles. If the cause can be identified and eliminated, the prognosis is good.

Although the exact cause of peripheral neuritis is unknown, it’s thought to be mediated by inflammation, ischemia,

and demyelination of the larger peripheral nerves, as a result of diabetes, alcohol use, and Guillain-Barré syndrome.

and demyelination of the larger peripheral nerves, as a result of diabetes, alcohol use, and Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree