Chapter 13 Nerve Root, Sacral, and Pelvic Stimulation

Stimulation of sacral nerve roots from within the spinal canal is an important technique to consider for the treatment of many forms of chronic pelvic pain, including epididymoorchialgia, vulvodynia, and interstitial cystitis; urinary control problems; and other forms of pelvic floor dysfunction and bilateral foot pain.

Stimulation of sacral nerve roots from within the spinal canal is an important technique to consider for the treatment of many forms of chronic pelvic pain, including epididymoorchialgia, vulvodynia, and interstitial cystitis; urinary control problems; and other forms of pelvic floor dysfunction and bilateral foot pain. A transforaminal placement from a cranial to caudal orientation is often the best way to obtain the stimulation pattern desired with a low migration rate.

A transforaminal placement from a cranial to caudal orientation is often the best way to obtain the stimulation pattern desired with a low migration rate. A “laterograde” approach to gain cephalad access is easier to perform and improves the learning curve.

A “laterograde” approach to gain cephalad access is easier to perform and improves the learning curve. The more lateral the entry site, the more shallow is the angle of the needle to the dura, and the easier the access.

The more lateral the entry site, the more shallow is the angle of the needle to the dura, and the easier the access. The needle is perpendicular to the skin in craniocaudal orientation—the entire angle is mediolateral.

The needle is perpendicular to the skin in craniocaudal orientation—the entire angle is mediolateral. When placing bilateral electrodes, allow the needle tips to nearly “kiss” in the midline, then turn the bevels caudally to pass the electrodes.

When placing bilateral electrodes, allow the needle tips to nearly “kiss” in the midline, then turn the bevels caudally to pass the electrodes. For transforaminal placement keep the electrode in the midline until the last minute; then roll laterally into the foramen only about a vertebral level from target.

For transforaminal placement keep the electrode in the midline until the last minute; then roll laterally into the foramen only about a vertebral level from target. In patients with prior lumbar surgery, the epidural space may be obliterated. Get appropriate imaging.

In patients with prior lumbar surgery, the epidural space may be obliterated. Get appropriate imaging. Many practitioners are less familiar with sacral radiographs. Make use of lateral films to verify level.

Many practitioners are less familiar with sacral radiographs. Make use of lateral films to verify level. Avoid the tendency to aim the needle caudally at the entry site. The shingling of the laminae makes it difficult to gain entrance this way.

Avoid the tendency to aim the needle caudally at the entry site. The shingling of the laminae makes it difficult to gain entrance this way.Introduction

Brindley1 performed the first implantation of a sacral anterior root stimulator in a patient with multiple sclerosis who suffered from impaired bladder emptying and incontinence in 1976. Since then, sacral neuromodulation has evolved rapidly, with the development of several different anatomic approaches and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of a specific device in 1997 for the treatment of urge incontinence and frequency-urgency syndrome and nonobstructive urinary retention in 1999.2–6 Sacral neuromodulation has also been shown to be efficacious in the treatment of chronic pelvic pain syndromes such as interstitial cystitis (IC), vulvodynia, prostadynia/epididymoorchialgia, sacroiliac pain, and coccygodynia.

Establishing the Diagnosis

Interstitial Cystitis

Interstitial cystitis (IC) is a chronic, often debilitating condition with symptoms of urinary urgency and frequency associated with suprapubic or pelvic pain with bladder filling in the absence of urinary tract infection (UTI) or other obvious pathology.7–12 The diagnosis of IC can be made in patients with characteristic cystoscopic findings of glomerulation or Hunner ulcers (10%) along with clinical findings.12,13 The histological findings are consistent with neurogenic inflammation.13 The prevalence varies across studies least in part because of differing diagnostic criteria, but it is in the range of 45 to 197 per 100,000 women and 8 to 41 per 100,000 men14,15 The pathogenesis and natural history are not completely understood but appear to be multifactorial,12,15 including infection, allergic, immunological, and genetic processes.12,15 The most popular theory is that a sequence of toxic reactions follows damage to the bladder epithelium, resulting in a severe inflammatory reaction that induces neurogenic pain and bladder irritation.9,12,16,17 Other chronic pelvic conditions may mimic this process with minimal differences. The European Society for the Study of Interstitial Cystitis (ESSIC) has proposed a new nomenclature and classification system with the name of painful bladder syndrome.18 Patients without classic cystoscopic or histological findings were included in these criteria.

IC is typically associated with other chronic debilitating conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), migraine, fibromyalgia, asthma, incontinence, or vulvodynia, and is commonly associated with a history of abuse.12,14,19,20 The differential diagnosis includes a variety of similar conditions such as overactive bladder (OAB), chronic pelvic pain (CPP), vulvodynia, UTI, or even endometriosis.15

Vulvodynia

Vulvodynia is a chronic stinging, burning, itching, or irritating pain in the vaginal region without evidence of infectious, inflammatory, or neoplastic causes or any underlying neurologic disorder.21–23 The estimated prevalence is more than 2 million women in the United States.24 This chronic condition has debilitating effects on both physical and psychological aspects of the patient’s life.22 The pathology is not well understood. Hormonal and immunologic factors that stimulate nociceptive nerve endings directly or lead to local inflammatory signals can cause neuropathic pain of this kind.22 Clinical symptoms occur in episodes with irregular intervals. The diagnosis is one of exclusion. Both a gynecologist and urologist should evaluate the patient to make this diagnosis. The mainstays of therapy are dietary changes, physical therapy, psychological and sexual counseling, and oral or local medications under the guidance of pain specialists.22,23,25

Chronic Testicular Pain

Chronic testicular pain is pain in the scrotal or testicular area lasting for more than 3 months and interfering with daily activities and quality of life. It is also called chronic orchialgia, orchiodynia or chronic scrotal pain syndrome.26,27 It typically occurs in patients with infectious, inflammatory, vascular, postsurgical, or neoplastic conditions. Detailed examination by a urologist with proper investigations to rule out treatable causes is the primary initial focus in patient evaluation.

Prostadynia

Prostadynia is defined as chronic genital or perineal pain associated with urinary urgency and dysuria. It is seen in 5 of every 10,000 outpatient visits. National Institutes of Health (NIH) criteria differentiate this from CPP syndrome based on the presence or absence of leukocytes in expressed prostatic secretions, postprostatic massage urine, or seminal fluid analysis.13 Some authors suggest that this pathological process in males is similar to IC in females.28

Coccygodynia

Coccygodynia is a painful syndrome limited to the coccyx; it may be aggravated by sitting or standing up. The process is commonly attributed to fractures or soft tissue injuries, but many cases are idiopathic.29 Coccygodynia is extremely challenging to treat. Options include rubber ring cushions, sacrococcygeal rhizotomy, physiotherapy, local injections, coccygectomy, and neuromodulation.13

Basic Science

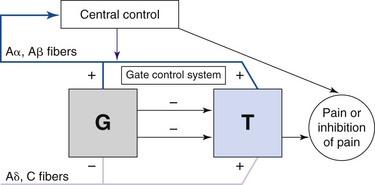

Spinal cord or nerve root neuromodulation for pain was initially explored based on the gate control theory introduced by Melzack and Wall,30 which suggested that activation of large-diameter afferent fibers (Aβ) suppressed pain signals travelling to the brain (Fig. 13-1). Since its adoption for widespread clinical use, it has become clear that for electrical neuromodulation to be successful, the following criteria must be met:

The anatomical distribution of the paresthesia is primarily determined by the location of the cathode, or negative contact, often referred to as the active contact.

The anatomical distribution of the paresthesia is primarily determined by the location of the cathode, or negative contact, often referred to as the active contact. Alternative positions of the anode, or positive contact, can “pull” the perceived stimulation in a desired direction or “shield” other areas by hyperpolarizing them.

Alternative positions of the anode, or positive contact, can “pull” the perceived stimulation in a desired direction or “shield” other areas by hyperpolarizing them.Shaker and colleagues31 suggested that neuromodulation acts by inhibiting signal transmission to the central nervous system (CNS) via C fibers, but chronic neuropathic pain conditions can also induce new neural activity in second-order neurons in the CNS, shifting the focus of activity.13 Matharu and associates32 showed that successful stimulation may change thalamic metabolism and remodel the intrinsic pain circuits. Thus neuromodulation can be applied to many neuropathic pain conditions.

Pelvic pain syndromes appear to be neuropathic in nature, with characteristics of hyperpathia and allodynia.13 Histological findings in both IC and vulvodynia suggest neurogenic inflammation.33–35 In addition, 40% of women with IC have a history of hysterectomy, suggesting that injury may lead to transient inflammation, which resembles reflex sympathetic dystrophy.13

Imaging

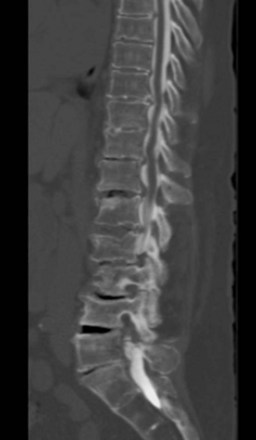

No specific imaging techniques are available that demonstrate the pathological changes that cause neuropathic pain disorders such as CPP and coccygodynia. Imaging is directed at ruling out other causes of the symptoms such as infection or spinal pathology and for delineating anatomical difficulties in applying neuromodulation techniques such as spina bifida, previous surgical sites where the epidural space is obliterated, severe spondylolisthesis, or severe stenosis, which would make placing epidural electrodes more difficult or impossible (Fig. 13-2).

Indications/Contraindications

General Indications

Sacral intraspinal NRS is commonly used for36:

The transforaminal approach is commonly used for36:

The extraforaminal approach is commonly used for36:

Absolute Contraindications

Any process that obliterates the epidural space is a contraindication to epidural placement over that location (e.g., previous laminectomy at that level). Computed tomography (CT) scan best shows bony removal from previous operation; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium is the best test to show scar formation.

Any process that obliterates the epidural space is a contraindication to epidural placement over that location (e.g., previous laminectomy at that level). Computed tomography (CT) scan best shows bony removal from previous operation; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium is the best test to show scar formation. Severe psychiatric disease such as personality disorders, severe depression and other mood disorders, somatoform disorders, or somatization

Severe psychiatric disease such as personality disorders, severe depression and other mood disorders, somatoform disorders, or somatizationStay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree