(1)

Neurosurgical Department, Friederiken-Hospital, Hannover, Germany

13.1 Types, Symptoms, and Diagnosis

Most types of nerve tumor are characterized by the same slowly proceeding symptoms that we consider as typical of all the other previously mentioned focal neuropathies. Therefore, it normally takes several months to find the correct diagnosis and to differentiate from alternative neuropathies. Either the patient notices a focal swelling in his extremity not on a particular day, or eventually increasing symptoms give reason for imaging examination which leads to finding a tumor.

In the following, we restrict ourselves to benign space-occupying lesions either located extra- or intraneurally for which a revised overview was recently published in literature [1]. In all of these cases, the slowly increasing space-occupying effect on nerve axons causes the typical electric-current like paresthesias, in other words, the typical Tinel sign, which characterizes all kinds of focal neuropathies with partial or complete loss of axon continuity (see Sect. 4.1). The point where these sensations are felt most strongly indicates the location of degenerating and regenerating neuronal sprouts. First, patients repeatedly notice the location of their sensation, and then they sometimes observe something like a tumor mass which is movable transverse to the nerve course. Later, it becomes more and more sensitive.

Neurological deficits occur rather late. Unfortunately, electrodiagnostic testing is of subordinate value to find the diagnosis because it cannot reveal the correct pathology (see Chap. 5). However, imaging either as high resolution ultrasound or as magnetic resonance imaging is of superior value, and it should therefore be arranged in any case (see Sects. 6.1.7 and 6.2.7).

13.2 Surgical Considerations and Prognosis

The introduction of microsurgery has extended our surgical horizons in tumor cases. Results have massively improved so that it seems increasingly difficult to justify cases where the involved nerve is completely sacrificed. As to be expected, secondary nerve repair after nerve sacrifice achieves a lower functional level than a microsurgical primary procedure with preservation of unaffected nerve fibers (Fig. 13.1).

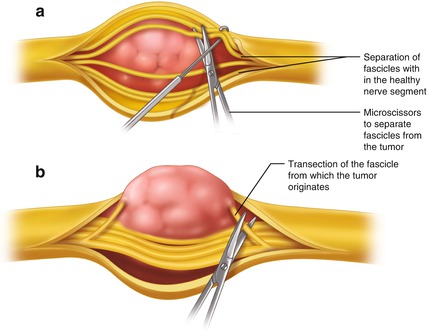

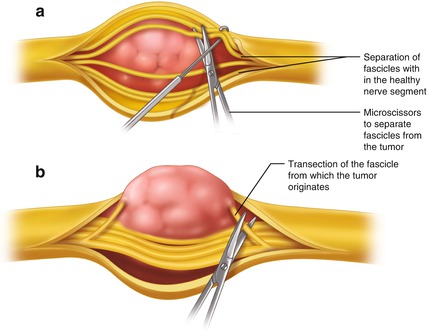

Fig. 13.1

Principles of microsurgery of a schwannoma. (a) Exposure of fascicles proximally and distally to the tumor as the first step. (b) Identification of the originating fascicles at the tumor poles, their transection, and then complete tumor removal as the final step

Therefore, surgery seems mandatory in all kinds of benign histology and solitary manifestation. In most of all cases, imaging findings are sufficient to define the entity as a benign one what will facilitate to decide to operate on. The question about solitary or multiple tumor occurrences in a limb can be solved more easily by means of ultrasound because MRI is technically restricted for certain limb segments. Because most nerve tumors are revealed as solitary, they have to be assessed as easily and primarily accessible; thus we should not hesitate to apply our microsurgical experience and remove the pathology completely.

As a principle, the exposure of all kind of benign tumor first requires skin incisions large enough to identify the uninvolved nerve structure above and below the tumor. A few centimeters of the entering and exiting nerve segments should be visible, because the microsurgical procedure better starts from these healthy nerve segments. Its epineurium is longitudinally incised and perhaps partially removed so that a careful separation of fascicle groups is possible. The whole procedure is comparable to what we previously described in Sect. 7.1 as “interfascicular” neurolysis. Especially less experienced surgeons should make it a habit to start with these principles, because most of the fascicles and fascicle groups divide and disappear between the outer layers of the tumor sheath. These fibers are easier to identify and preserve when the surgeon arrives at the tumor mass with all fascicle groups in view from the beginning. They occur all over the whole tumor circumference. Under the microscope they can be carefully separated from the tumor and, sometimes, micro-scissors are needed for dissection. At the end, they remain preserved anatomically and functionally. When you finally return to the entering and exiting nerve segments, at least in cases of neurinomas, you will identify one fascicle or a small fascicle group from which the tumor originates. This small structure must be transected above and below the tumor so that you can take out the tumor and close the wound [2].

As the anatomically visible fascicular nerve pattern at different levels does not simultaneously correspond to a functional grouping, the sacrifice of the involved fascicle or fascicle group does not result in a noticeable neurological deficit. Mostly, nerve fibers from which a tumor originates have already lost their function during the growth of the tumor. The functional loss is then commonly pre-operatively compensated. It is therefore reasonable that the prognosis of most benign tumor surgery is extremely good provided the tumor addressed early enough and no other surgeon has previously tried to remove it macroscopically.

Special considerations are needed if structures of the brachial plexus, especially at trunk level, are involved. The nerve tissue differs from more peripheral nerve segments insofar as the typical inter-fascicular pattern is absent in favour of a mono- or bi-fascicular structure. We find fewer collagen fibers within plexus trunks, and a perineural layer which envelops several fascicle groups is lacking. Therefore, supra-clavicular nerve trunks have less resistance to surgical manipulation. Nevertheless, by means of all our microsurgical efforts, a complete removal of a solitary brachial plexus tumor is less difficult than perhaps expected [3].

To summarize on prognosis, the surgical principles described above can always be applied to neurinomas (schwannomas) which represent the most common nerve tumor occurrence in humans. Consequently, they have excellent prognosis, independent of their location.

Neurofibromas, however, differ insofar as the nerve structure from which they originate includes more fascicles, sometimes a whole fascicle group. Removal of such a tumor results in a slightly more functional sacrifice, but, nevertheless, its prognosis remains excellent [2].

In contrast to that, plexiform and multiple neurofibromas need quite another approach on prognosis than we would expect, taking into account the solitary tumors just mentioned [2]. The same holds true in rare cases of perineurioma, previously termed “local hypertrophic neuropathy” [4]. Both entities would theoretically need a complete nerve trunk resection and repair by grafts, but hardly any surgeon could bear responsibility for such a sacrifice.

Again, different comments on prognosis are needed in cases of intraneural multiple ganglia [5]. However, provided that microsurgical principles are kept in mind, the surgical prognosis is almost as good as for solitary neurinomas.

Special remarks on all benign nerve tumors will follow. It applies to all of these lesion types that a microsurgical step-by-step procedure remains the key to preserve the nerve function. Prognosis will then remain at a high level and independent of the availability of high-end diagnostic tools. Under magnification, the surgeon can, step by step, visualize all the details needed to decide and proceed correctly.

13.3 Special Comments on Different Tumor Types

13.3.1 Schwannomas (Neurinomas)

These tumors originate from Schwann cells of one single fascicle. Several manifestations within one nerve trunk may rarely occur, but then each time originate from another fascicle.

Independent of the location, microsurgical removal always succeeds without any significant functional deterioration [2]. Even schwannomas of the brachial plexus in the supraclavicular area can be completely removed as described [3]. The surgeon then needs to remember that the fascicular pattern differs from nerve segments located in the periphery insofar as nerves at trunk level are mono- or bi-fascicular and with less collagen filaments inside. The challenge to microsurgical abilities is a little bit higher, but the prognosis to remove the tumor completely is excellent. A recurrence is only to be considered when fascicle involvement already starts at a very high level in the neuroforamen. These patients will need a follow up by MRI examination over the years and perhaps a second neurosurgical spine approach.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree