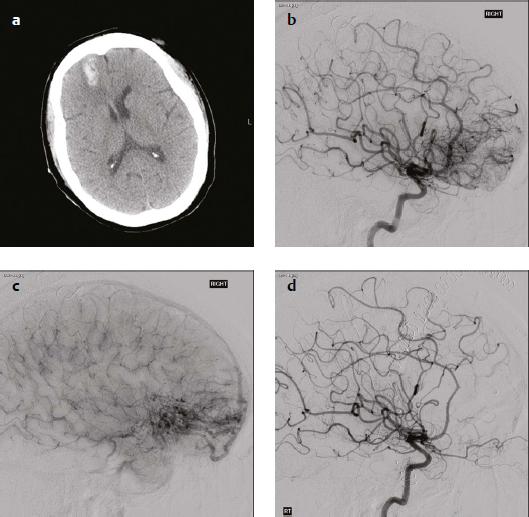

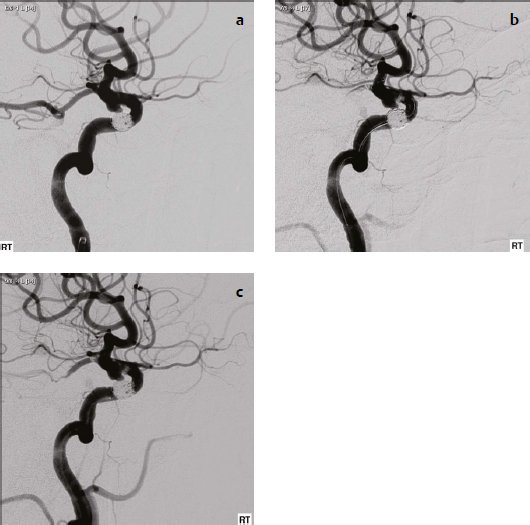

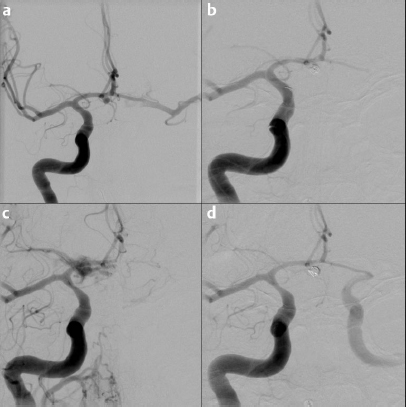

22 Anticoagulation management is an important aspect of endovascular neurosurgical interventions. This chapter presents specific cases to highlight the anticoagulation regimen employed. For each case, a short discussion explains the course of action and suggests other reasonable management options for similar circumstances. A 40-year-old woman presented with a new onset of seizure. Clinically, she was neurologically intact. Computed tomographic (CT) scan showed a right frontal intraparenchymal hemorrhage, and CT angiography demonstrated abnormal vessels consistent with a Spetzler-Martin grade 2 arteriovenous malformation (AVM) (Fig. 22.1). Given her age, good clinical examination, ruptured status, and accessible location of the AVM, a preoperative embolization followed by surgical resection was planned. The procedure was performed under general anesthesia 2 days after her presentation. Systemic heparinization was not performed, given her recent hemorrhage. After femoral access was obtained, angiography was performed that demonstrated the AVM to be fed by the medial orbitofrontal and frontopolar branches of the anterior cerebral artery (Fig. 22.1b,c). Embolization of the lesion was performed using 1:3 mixture of N-butyl cyanoacrylate (NBCA) glue and Ethiodol, without complication (Fig. 22.1d). Surgical resection was planned for the following day, and the patient was left intubated in the interim because of a difficult airway. Because an intraoperative angiogram was anticipated, the femoral sheath was left in place with a 1:1 mixture of heparinized saline solution (500 cc normal saline with 500 units of heparin) infusing at 15 cc/hour overnight. The patient underwent surgical resection the following day, with intraoperative angiography demonstrating no residual lesion. The sheath was removed in the intensive care unit postoperatively by applying manual pressure for 15 minutes. The patient was left intubated for blood pressure control overnight and was extubated the next day. She remained neurologically intact. No systemic heparinization was performed during this procedure because of her recent intracranial hemorrhage due to AVM rupture. If surgical resection with intraoperative angiography is planned for the following day, the option of leaving the sheath in place is a reasonable one, especially if the patient is to remain intubated. This avoids the patient having to undergo multiple femoral punctures each with a risk of groin complications. However, if the patient is extubated between the embolization and surgical procedures, excessive leg movement with the sheath in place may also lead to complications such as arterial dissection. If the sheath is left in place, femoral thromboembolic complications can be avoided by an infusion of heparinized saline solution. A 73-year-old woman, a smoker with a history of migraine headaches, experienced the sudden onset of retro-orbital pain behind her left eye. She did not seek medical care initially, even though the usual treatments for her migraines did not relieve her symptoms. About 10 days later she developed difficulty speaking, after which she presented to her physician. Clinically, she was neurologically intact with the exception of moderate expressive dysphasia. Imaging included a magnetic resonance (MR) angiogram that demonstrated a 6-mm left-sided superior hypophyseal aneurysm, and a right-sided 4-mm superior hypophyseal aneurysm. Magnetic resonance fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) imaging showed leptomeningeal signal in the left sylvian fissure, suggestive of past hemorrhage, and diffusion-weighted imaging demonstrated several subacute strokes in the left middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory. The patient underwent urgent coil embolization of the left superior hypophyseal aneurysm, due to presumed rupture. One month later, she was readmitted electively for planned coil embolization of her right superior hypophyseal aneurysm. Systemic anticoagulation was administered with 70 U/kg of intravenous heparin after groin access was obtained. After initial angiography, it was felt that a stent would be required to successfully coil the wide-necked aneurysm (Fig. 22.2a). The stent was deployed successfully. Then attention was turned to advancing the microcatheter into the aneurysm. The acute angle between the aneurysm and the parent vessel of the aneurysm made it technically difficult to direct the microcatheter directly into the aneurysm. For this reason, the decision was made to advance a balloon para-axially to assist with keeping the microcatheter directed into the aneurysm. After the balloon was maneuvered into the region of the aneurysm, an angiogram through the guide catheter was performed. It demonstrated a filling defect within the stent and within the posterior communicating artery consistent with acute thrombus formation (Fig. 22.2b). The balloon was immediately removed from the patient. A total of 8 mg of abciximab was injected through the microcatheter, with its tip sitting just proximal to the stent. Angiography through the guide catheter was then performed demonstrating some, but not complete, resolution of the thrombus within the stent, and improved flow through the posterior communicating artery (Fig. 22.2c). Given the difficulty in catheterizing the aneurysm and the subsequent thrombus formation, the attempted coiling procedure was aborted. The patient was allowed to awaken from general anesthesia and was loaded on acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) 325 mg and clopidogrel 300 mg 4 hours after groin closure. Her immediate postoperative course was uncomplicated and she was discharged the following day. One month later, she underwent uncomplicated balloon-assisted coiling of the right superior hypophyseal aneurysm through the previously placed stent. There are several important points to learn from this case. Based on clinical history, there is suspicion that the patient’s headache represented an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Her difficulty speaking and her strokes were likely caused by vasospasm secondary to the hemorrhage. Despite this, systemic heparinization was performed soon after groin access was obtained, because the risk of rehemorrhage from anticoagulation was thought to be low. In comparison, acute subarachnoid hemorrhage patients who undergo coiling procedures are typically not heparinized until after the first coil is placed, although there is some variation in this practice. The placement of a stent for the patient’s wide-necked aneurysm was not anticipated. Therefore, premedication with ASA and clopidogrel was not prescribed before the second procedure, which would have reduced the chance of a thromboembolic complication. Furthermore, technical factors including the acute angle between the aneurysm and the parent vessel increased the length of time required for the procedure. The delay between placement of the stent and administration of the antiplatelet agent abciximab, and the use of a balloon as an additional adjunctive device also contributed to thrombus formation. When thrombus is observed, it is important to immediately remove devices that are contributing to its formation and that are no longer required, such as the balloon in this case. After administering abciximab, it was important to abort the attempted coiling procedure, as was done in this case. Further attempts at coiling can disrupt the thrombus and cause it to migrate distally, resulting in a stroke. Also, because the unruptured aneurysm had not yet been treated, the risk of a major hemorrhage with inadvertent aneurysmal perforation after administration of abciximab would be significant. Aborting the procedure and awaking the patient also allows for an examination to assess for any neurologic injury. Because thrombus formation required the catheters to be pulled proximal to the stent, aborting the procedure also enables integration and endothelialization of the stent before a reattempt at coil embolization, in this case occurring 4 weeks later. A 46-year-old healthy, non-smoking, right-hand-dominant man from a rural town suffered a sudden-onset headache associated with nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and neck stiffness. He was seen at a local hospital, and a CT scan revealed thick subarachnoid blood in the basal cisterns and in the anterior interhemispheric fissure with no evidence of hydrocephalus. CT angiogram revealed a 6-mm bilobed anterior communicating artery aneurysm directed anteriorly with a relatively narrow neck. He received a 1000-mg intravenous dose of tranexamic acid and was urgently transferred via air ambulance to a tertiary care center with neurosurgical services. Clinically, he was neurologically intact. The patient proceeded to undergo urgent unassisted endovascular coiling of the ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm under general anesthesia. The diagnostic angiogram via the right internal carotid artery (ICA) confirmed the presence of the aneurysm arising from the right A1/A2 junction with good cross-filling into the left anterior cerebral artery (ACA) and middle cerebral artery (MCA) branches through the anterior communicating artery (Fig. 22.3a). A microcatheter was advanced into the aneurysmal sac. Prior to insertion of the first coil, however, there was a small-volume rupture confirmed with injection via the guide catheter. This resolved spontaneously without any hemodynamic changes. After the first coil was deployed, the patient received systemic anticoagulation with 70 U/kg of intravenous heparin (Fig. 22.3b). A second coil was then deployed, after which there was a second, larger intraprocedural rupture (Fig. 22.3c). This was associated with hypertension (190/100 mm Hg) and bradycardia (heart rate of 40). In response, protamine was immediately administered by the anesthetist to reverse the heparin. Given that more than 30 minutes had elapsed since the initial administration of heparin, 5 mg of protamine for every 1000 units of heparin was given, and additional coils were placed to protect the fundus of the aneurysm. A right frontal external ventricular drain (EVD) was placed on an emergent basis in the angiography suite. An angiogram performed 3 minutes after the second rupture showed no further contrast extravasation. A control angiogram revealed good flow through the bilateral A1 and A2 branches and good flow through the distal branches (Fig. 22.3d). The procedure was then terminated.

Neuroendovascular-Specific Patient/Case Examples

Arteriovenous Malformation

History

Procedure

Discussion

Aneurysms: Case 1

History

Procedure

Discussion

Aneurysms: Case 2

History

Procedure

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree