Chapter 8 Neurogenic disorders of speech, language, cognition-communication, and swallowing

Globalization has compelled ways of thinking that express a model for inclusion in its highest and purest form. As such, notwithstanding cultural peculiarities (Geertz, 1983), people around the world can no longer overlook the universality of many aspects of the human existence, including its nature, behavior, and environment. For instance, demographers of aging show global trends that reflect significant increases in the numbers of individuals, both within the United States and internationally, who are living longer and living longer with disabilities. The hallmark of this global demographic shift is the explosion in the growth of nonwhite populations. It is therefore imperative that a multicultural worldview be embraced, cultivated, and promoted when working with individuals with neurogenic communication and swallowing disorders. The World Health Organization (WHO) responded to the call for integral inclusion of personal and cultural factors related to health and disability, including communication disorders, when developing the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF, 2001). Further, evidence-based practice (EBP) for communication disorders integrates within its framework clinician’s expertise, current best evidence, and client values and preferences. According to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (2010), the goal of EBP is “ . . . to provide high quality services that reflect the interests, values, needs, and choices of the individuals we serve.” Threats (2010) contends that both the ICF model and EBP are client-based approaches; therefore, integration of the tenets of both will ensure culturally relevant rehabilitation outcomes.

Who ICF model and neurogenic communication disorders

Evidence-based practice

EBP can be defined as the clinician’s “conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients” (Sackett et al., 1996, p. 71). For communication sciences and disorders, EBP is a process in which the clinician systematically gathers and integrates information from a variety of resources, including scientific evidence, prior knowledge, and client preferences, to arrive at a decision (Justice, 2008). To this definition, the context in which services are delivered has been added. Therefore, EBP is grounded in the following four types of evidence: external evidence, clinical expertise, client values and preferences, and service delivery context.

External evidence includes both scientific research and objective performance measures (i.e., test results, direct patient observation, and ancillary reports from other health professionals) used by clinicians to evaluate and monitor progress. Clinical expertise is acquired through experience, continuing education, and consensus building among professionals and allows us to provide services in areas in which scientific evidence is absent, incomplete, or equivocal. Client values and preferences enable us to serve individuals appropriately by taking into account personal and individual factors (i.e., beliefs, communication style, language choice). Incorporating client values and preferences throughout the clinical management process ensures the delivery of culturally competent professional services. The service delivery context includes the pressures, policies, and practices of employment facilities, government agencies, and other regulatory bodies that have an unavoidable and profound effect on practice patterns (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association [ASHA], 2010; Gottfred, 2008).

Cultural competence

Culture and communication are integrally related. Individuals express held cultural views, values, beliefs, and preferences by means of verbal and nonverbal communication as well as in behaviors and actions. Cultural anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1983) asserted that “culture is always local.” If one espouses to this way of thinking about culture, it is clear to see how egocentricity (self-interest) too often prevails over altruism (selflessness). Examination of egocentricity is essential in communication disorders. Paul and Elder (2009) state that:

Cultural competence deals with attitudes and behaviors that dictate a person’s actions. Accordingly, it “ . . . is a set of cultural behaviors and attitudes integrated into the practice methods of a system, agency, or its professionals, that enable them to work effectively in cross cultural situations” (Administration on Aging [AoA], 2010). In this view, there are two dimensions to cultural competence: surface structure and deep structure (AoA, 2010; Myers, 1987). Surface structure deals with understanding the people, including the beliefs and values they hold and the language, traditions, music, food, and clothing familiar to and preferred by them. Deep structure involves understanding sociodemographic and racial/ethnic population similarities and differences, and the influences of ethnic, social, cultural, historical, and environmental factors on behaviors. Specific to communication disorders, Battle (2002) characterizes the essence of cultural competence as follows:

Of import in Battle’s characterization are (1) the impact of culture for effective and efficient communication, and (2) that all individuals view and interpret the world from the perspective of their own cultural lens (see Klein, 2004). There are some basic tenets of cultural competence for clinicians providing services to individuals from multicultural and international populations who have neurogenic communication and swallowing disorders. First, one must understand the demographics of normal and pathologic aging. This is particularly important because persistent and significant health disparities exist among U.S. populations as well as non-U.S. populations, and because of the specific diseases and disorders that lead to neurogenic communication and swallowing disorders. Second, there are some identified differences in the neuropathophysiologic changes and neural recovery patterns that are driven by race and ethnicity. Complete understanding of the impact of the differences in brain structure and function will effectively inform patient-based clinical management. Third, evidence-based clinical practice accommodates for the cultural competence of the health professional within its framework; this tenet assumes reflection on and integration of the sociodemographic and sociocultural values and preferences of the patient throughout the clinic decision-making process (see Threats, 2010).

Clinicians who fully understand the influence of cultural and linguistic diversity in research and practice appreciate the significance of adopting a culturally competent, evidence-based approach to their clinical and professional pursuits. It is possible that providers of culturally competent services will see improved patient participation, increased compliance, and improved follow-up. A systematic, qualitative review of the literature showed excellent evidence that cultural competence training can (1) favorably affect knowledge of attitudes of health care providers, and (2) improve their attitudes and skills when working with individuals from various racial/ethnic backgrounds (Levine et al., 2004). Similarly, good data suggest that cultural competence training will improve patient satisfaction, although it is yet unclear what the impact is on patient adherence (Agency for Health Care Research and Quality, 2004).

Epidemiology of neurogenic communication and swallowing disorders

Epidemiologic data on neurogenic communication and swallowing disorders are severely limited. Epidemiology is the study of the distribution and determinants of health-related states or events in a specified population, taking into account factors (e.g., inequalities, community, family, work) and risks (e.g., habits, genetics, lifestyle) that influence patterns of health and disease for the purpose of understanding how to control and prevent health problems (Enderby & Pickstone, 2005). Increased attention to prevention in the current health care climate makes it imperative for speech-language pathologists to understand the principles of epidemiology and how epidemiologic data can inform clinical practice (Enderby & Pickstone, 2005; Lubker, 1997). This is particularly salient for clinicians who work with older individuals. Three factors are critical to understanding issues in working with older persons. First, there is a high prevalence of diseases and disorders of the brain in this population. Second, there is a significant increase in individual and group differences due to unique life experiences or circumstances. Third, there are increasing numbers of aging individuals who do not speak American English (e.g., recent immigrants), who do not speak English well, who speak English as a second language, or who speak more than one language.

Neuropathophysiologic diversity

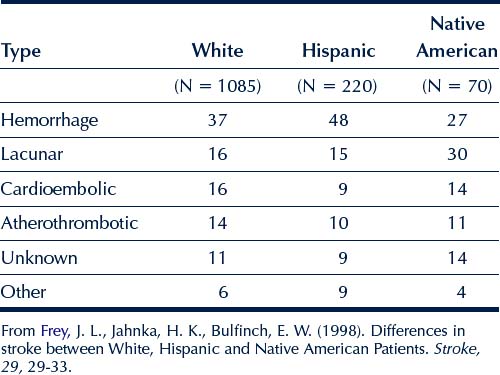

Research has provided limited but compelling evidence for cultural variability (race and gender) in the distribution of neurologic lesions in stroke (see Table 8-1; Gorelick, 1998; Li, Lam, & Wong, 2002). Notably, African Americans, Japanese, and women tend to show a prevalence of intracranial (within the skull/cranium; see Markus et al., 2007) lesions affecting small arteries such as those located in the subcortical and midbrain regions. White males, on the other hand, show an overwhelming prevalence of extracranial (outside of the cranium) lesions that affect the large carotid arteries. Frey and colleagues (1998) reported lesion distribution data for Hispanics/Latinos, Native Americans, and whites. They found few significant differences between the races for type of stroke. As shown in Table 8-1, Native Americans (30%) had a greater prevalence of stroke related to lacunes than either whites (16%) or Hispanics (15%). Whites (16%) had a greater incidence of stroke related to cardioembolism than Hispanics (9%). There was no difference in the strokes related to hemorrhagic, atherothrombotic, or other types of stroke. Although these trends appear to be stable, additional research is needed to determine the implications of these racial and ethnic and gender differences. It is possible that, in addition to other prognostic factors such as size and site of lesion, age of onset, premorbid education level and social functioning, and family support, the distribution of the lesion may have implications for differences in neurobehavioral expectations (i.e., the particular deficits or skill sets of an individual after stroke) and assessment and treatment outcomes. The latest research shows that combination or tandem intracranial and extracranial arterial occlusions are found in a unique group of patients (Malik et al., 2011). These patients generally show a poor prognosis and, to date, race-ethnicity has yet to be identified as a distinct feature in this group of patients.

Neurogenic communication and swallowing disorders

Neurologic disorders of communication and swallowing result from a variety of diseases of the brain and nervous system, including demyelinating, degenerative, inflammatory, systemic, cardiovascular, extrapyramidal, episodic and paroxysmal, nerve, nerve root and plexus, polyneuropathies and other disorders of the peripheral nervous system, myoneural junction and muscle, cerebral palsy and other paralytic syndromes, as well as other disorders of the nervous system (ICD, 2010). Adult (acquired) neurogenic language disorders include aphasia, alexia, agraphia, and cognitive-communicative disorders secondary to stroke, dementia, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), traumatic brain injury (TBI), and right hemisphere damage (RHD). Acquired neurogenic speech disorders include apraxia of speech (AOS) and the dysarthrias. Approximately 24% of individuals who experience stroke have primary speech impairments following brain damage (see Byles, 2005). Acquired neurogenic swallowing disorders (also referred to as dysphagia) range from oral to oropharyngeal to pharyngeal to esophageal dysphagia. Dysphagia is highly prevalent among stroke patients; 45% to 65% of these patients will experience swallowing difficulties within 6 months after the onset of stroke (Schindler & Keller, 2002). It is impossible to cover, with any depth, the vast collection of research and clinical practice information on acquired neurogenic communication and swallowing disorders in this chapter. Payne (1997) and Wallace (1997) have focused specifically on adult neurogenics in multicultural populations. Others have focused on communication disorders in multicultural populations over the life span that included adult neurogenics (e.g., Battle, 2002). The following section presents a brief overview of major acquired language disorders of aphasia and cognitive-communicative impairments secondary to dementia, TBI, and RHD. Included in the discussion is the available research on incidence and prevalence of each of the disorders in multicultural and international populations.

Aphasia

Aphasia is a disruption in one or more language modalities, including comprehension of language, speech production, reading, writing, and gesturing, that can significantly impair one’s ability to communicate her or his needs, wants, feelings, and ideas and, therefore, adversely affects the person’s quality of life. Only a very small number of stroke patients completely recover from aphasia. It is widely held that, in most people, language is lateralized to the left hemisphere (also referred to as the language-dominant hemisphere), although new research suggests that there is no one-to-one correlation between where the lesion occurs in the brain and the type of aphasia (e.g., nonfluent, fluent, Broca’s, Wernicke’s, global) (Dronkers et al., 2004).

Stroke and neurogenic disorders of communication and swallowing

Recent data show that stroke or brain attack is the fourth most common cause of death in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010). The general rate of stroke in the United States is 2.6% of the population; however, according to the CDC (Neyer et al., 2005), the prevalence of stroke varies by education level, race and ethnicity, and geographic region. Risk factors related to education level include poverty and lack of economic opportunity, social isolation, and cultural norms for diet and exercise. They report that the prevalence of stroke varies across racial/ethnic groups in the United States is as follows: American Indians/Alaskan Natives (6.0%), multiracial (4.6%), African Americans/blacks (4.0%), Hispanics (2.6%), whites (2.3%), and Asians and Pacific Islanders (1.6%). According to the CDC data, African Americans/blacks, Hispanics, Asians and Pacific Islanders, and American Indians/Alaskan Natives die from a stroke at younger ages than whites. The report suggests that the higher prevalence of stroke in certain racial/ethnic groups may be related to higher incidence of chronic health conditions such as high blood pressure, heart disease, high cholesterol, diabetes, tobacco and alcohol use, inactivity, and obesity. Further, these data indicate that individuals who are at greater risk for stroke are also at greater risk for communication and swallowing disorders.

African americans

The frequency of stroke and stroke-associated mortality is approximately twice as high for African American males and females as it is in among whites (Gorelick, 1998). This disparity is most pronounced at younger ages. For example, African American men aged 45 to 59 years are about four times more likely to die of stroke than white men of the same age. By age 75 years or older, however, this ratio falls to about 1.26. In the United States, the disparity in the ratio of African American to Hispanic mortality is greatest for stroke.

Several of the known risk factors for stroke, such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity, are more common in blacks than whites, and sickle cell disease and HIV infection are stroke risk factors with particular relevance to Africans (Imam, 2002). Wertz and associates (1997) reported that there are several differences between strokes experienced by African Americans and those experienced by whites. African American women are more likely to have a stroke than African American males; among whites, there are minimal gender differences in the incidence of stroke. Among African Americans, the lesion leading to the stroke is more often located within the cranium (skull), whereas among whites, it is more often located outside the cranium. Among African Americans, after a stroke, physical and functional impairment is more severe, and functional improvement occurs at a slower rate than among whites. African Americans are particularly prone to aphasia owing to a higher incidence of stroke and stroke-related diseases such as diabetes and hypertension.

Pratt and colleagues (2003) reported that, as a group, African Americans have less knowledge about stroke, its risk factors, and prevention than whites. Those who have a history of diabetes, hypertension, or heart disease and who had a history of stroke in their family had more knowledge about strokes than those who did not have this history. Younger and college-educated African Americans had more knowledge about stroke and stroke prevention than those with less education, regardless of age.

A small group of researchers have investigated one aspect of aphasia (narratives) in African Americans. The results were mixed. Ulatowska and colleagues (2000, 2003) observed narrative style in African Americans with stroke. They reported that when blacks communicate with each other or tell stories, they have the tendency to repeat themselves or have other people repeat what they say. An example is that African American ministers encourage the congregation to repeat what they say in a call-and-response pattern during the sermon. Some African Americans with aphasia involuntarily repeat all or part of the utterances of speech partners, even when no one is talking about that subject anymore. In severe cases, the person may experience stereotypic self-repetition of single recurrent syllables, words, or phrases (Ulatowska, et al., 2000). On the other hand, Olness and associates (2010) recently reported no differences between African American and white persons with aphasia in assigning prominence to information in narratives.

Hispanics/latinos

An American Heart Association study conducted in the late 1990s reported that Hispanics between the ages of 45 and 59 years have more than three times the risk for suffering a stroke than non-Hispanic whites. Stroke is the fourth highest killer of Hispanics. Nearly 25% of all deaths in Hispanic men are due to stroke, and the number rises to 33% for Hispanic women (Gillum, 1995).

Frey and colleagues (1998) reported on differences in stroke types (see Table 8-1) and risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, cardiac disease, and smoking in 1700 white, Hispanic, and Native American stroke patients admitted to a hospital in Arizona. Mean age at stroke onset was significantly lower in Native Americans (56 years) than Hispanics (61 years) and whites (69 years). The mean age of onset of stroke for Hispanics was significantly lower than for whites. They report that hypertension was significantly more prevalent in Hispanics (72%) and Native Americans (71%) than whites (66%). Diabetes was significantly more prevalent in Native Americans (62%) than both Hispanics (36%) and whites (17%). Cigarette smoking was significantly more common in whites (61%) than either Hispanics (46%) or Native Americans (41%). Cardiac disease was significantly more prevalent in whites (34%) than Hispanics (24%). History of hypercholesterolemia was not significantly different between the races. Heavy alcohol intake was significantly more prevalent in Native Americans than Hispanics and whites and significantly more prevalent in Hispanics than whites.

Asians and pacific islanders

Although racial and ethnic disparities in the incidence of stroke and aphasia within the United States have been a recent interest, most studies have focused on African Americans and Hispanics, and few reports describe stroke in Asians and Pacific Islanders. However, stroke is a major concern in Asia. The stroke incidence rates in China and Japan are among the higher ones in the world. Reported incidence rates vary dramatically but are generally higher than those of the United States. For example, compared with incidence in the United States, reported rates for overall stroke are 39% greater in Japan, 23% greater in Taiwan, and 81% greater in Northern China. Stroke is the second leading cause of death in China, Korea, and Taiwan; third in Japan and Singapore; sixth in the Philippines; and tenth in Thailand. In 2005, there were a reported 1.4 million fatal strokes in China, including an annual 3000 in Hong Kong alone (Ng, 2007).

The variation in the proportion of stroke subtypes among Chinese populations could be as large as or larger than that between Chinese and Western populations. Zhang and colleagues (2003a, 2003b) reported that ischemic stroke is more frequent in Chinese than in Western populations. Overall, Asian and Pacific Islander adults are less likely than white adults to die from a stroke; they have lower rates of being overweight or obese, lower rates of hypertension, and are less likely to have hypertension, be obese, and be current cigarette smokers.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree