Neuromuscular and paroxysmal disorders

Neuromuscular disorders target the nerves, ultimately weakening the muscle. (See Motor neuron disease.) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, and myasthenia gravis are examples of neuromuscular disorders. Paroxysmal disorders are characterized by an involuntary episodic increase in symptoms that affect the neurologic system and include epilepsy and headache.

NEUROMUSCULAR DISORDERS

AMYOTROPHIC LATERAL SCLEROSIS

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig disease, is the most common motor neuron disease of muscular atrophy. ALS is a chronic, progressive, and debilitating disease that’s invariably fatal and is characterized by progressive degeneration of the anterior horn cells of the spinal cord and cranial nerves and of the motor nuclei in the cerebral cortex and corticospinal tracts.

The exact cause of ALS is unknown; however, about 10% of patients with ALS inherit the disease as an autosomal dominant trait. ALS may also be caused by a virus that creates metabolic disturbances in motor neurons or by immune complexes such as those formed in autoimmune disorders.

MOTOR NEURON DISEASE

In its final stages, motor neuron disease affects both upper and lower motor neuron cells. However, the site of initial cell damage varies according to the specific disease:

progressive bulbar palsy: degeneration of upper motor neurons in the medulla oblongata

progressive muscular atrophy: degeneration of lower motor neurons in the spinal cord

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: degeneration of upper motor neurons in the medulla oblongata and lower motor neurons in the spinal cord.

Precipitating factors that can cause acute deterioration include severe stress, such as myocardial infarction, traumatic injury, viral infections, and physical exhaustion.

ALS is about three times more common in males than in females and generally affects people ages 40 to 70. Although some patients may live as long as 10 to 15 years, most die within 3 years of diagnosis. Death usually results from such complications as aspiration pneumonia or respiratory failure.

Pathophysiology

ALS progressively destroys the upper and lower motoneurons. However, because it doesn’t affect cranial nerves III, IV, and VI, some facial movements such as blinking persist. Intellectual and sensory functions aren’t affected.

Some believe that glutamate—the primary excitatory neurotransmitter of the CNS—accumulates to toxic levels at the synapses. In turn, affected motor units are no longer innervated, and progressive degeneration of axons cause loss of myelin. Some nearby motor neurons may sprout axons in an attempt to maintain function, but ultimately, nonfunctional scar tissue replaces normal neuronal tissue.

Complications

Pneumonia

Respiratory failure

Aspiration

Complications of physical immobility

Assessment findings

Signs and symptoms of ALS depend on the location of the affected motor neurons and the severity of the disease and may include:

progressive weakness in muscles of the arms, legs, and trunk

muscle atrophy

muscle fasciculations (most obvious in the feet and hands)

difficulty talking, chewing, swallowing and, ultimately, breathing.

Diagnostic test results

Although no diagnostic tests are specific to this disease, the following tests may aid in its diagnosis:

Electromyography may show abnormalities of electrical activity of involved muscles; however, nerve conduction studies are usually normal.

Muscle biopsy may disclose atrophic fibers interspersed among normal fibers. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis reveals increased protein content in one-third of patients.

Computed tomography scan and EEG may help rule out other disorders, including multiple sclerosis, spinal cord neoplasms, syringomyelias, myasthenia gravis, and progressive muscular dystrophy.

Treatment

Because ALS has no cure, treatment focuses on controlling symptoms and providing emotional, psychological, and physical

support. Riluzole is a neuroprotective agent that may improve the patient’s quality of life and length of survival but doesn’t reverse or stop the disease progression. Baclofen or diazepam may be used to control spasticity that interferes with activities of daily living (ADLs). Trihexyphenidyl or amitriptyline may be used for impaired ability to swallow saliva. Gastrostomy may be needed early to prevent choking; referral to an otolaryngologist is advised. Physical therapy, rehabilitation, and use of appliances or orthopedic intervention may be required to maximize function. Devices to assist in breathing at night or mechanical ventilation may also be required.

support. Riluzole is a neuroprotective agent that may improve the patient’s quality of life and length of survival but doesn’t reverse or stop the disease progression. Baclofen or diazepam may be used to control spasticity that interferes with activities of daily living (ADLs). Trihexyphenidyl or amitriptyline may be used for impaired ability to swallow saliva. Gastrostomy may be needed early to prevent choking; referral to an otolaryngologist is advised. Physical therapy, rehabilitation, and use of appliances or orthopedic intervention may be required to maximize function. Devices to assist in breathing at night or mechanical ventilation may also be required.

Nursing interventions

Provide emotional and psychological support to the patient and his family.

Assist the patient with active and passive range-of-motion exercises.

Assist with ADLs and meals.

Establish a regular bowel and bladder elimination routine.

Provide good skin care and assess skin integrity every 2 to 4 hours, as appropriate.

Reposition the patient every 2 hours as the patient’s mobility decreases.

Provide an alternate means of communication if the patient develops difficulty talking.

Administer prescribed medications, as necessary, to relieve the patient’s symptoms.

Encourage deep-breathing and coughing exercises and use of incentive spirometry every hour while the patient is awake. Perform chest physiotherapy and suctioning every 2 to 4 hours, as appropriate.

Provide soft, semisolid foods and position the patient upright during meals. Administer tube feedings, as ordered, if the patient can no longer swallow adequately.

MODIFYING THE HOME FOR A PATIENT WITH ALS

To help your patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) live safely at home:

explain basic safety precautions, such as keeping stairs and pathways free from clutter; using nonskid mats in the bathroom and in place of loose throw rugs; keeping stairs well lit; installing handrails in stairwells and the shower, tub, and toilet areas; and removing electrical and telephone cords from traffic areas.

discuss the need for rearranging the furniture, and obtaining such equipment as a hospital bed, a commode, or oxygen equipment.

recommend devices to ease the patient’s and caregiver’s work, such as extra pillows or a wedge pillow to help the patient sit up, a draw sheet to help him move up in bed, a lap tray for eating, or a bell for calling the caregiver.

help the patent adjust to changes in the environment. Encourage independence.

advise the patient to keep a suction machine handy to reduce the fear of choking due to secretion accumulation and dysphagia. Teach him self-suction.

DISCHARGE TEACHING

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH ALS

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH ALSBefore discharge, teach the patient and his family:

about amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and its implications

treatment options, such as physical therapy and ventilation support

about prescribed medication administration, dosage, possible adverse effects, and when to notify the physician

the importance of good nutrition and what types of food may be best for the patient to handle and swallow

range-of-motion exercises to improve muscle tonicity and strength

about the types of therapy that would be beneficial, such as physical therapy, speech therapy, and occupational therapy

signs and symptoms of complications

methods to promote the patient’s independence and modify the home environment

the importance of follow-up care

the benefit of utilizing available community support groups such as the local chapter of the ALS Association.

Discuss end-of-life issues, as appropriate.

Discuss the home environment and provide recommendations for adjustments. (See Modifying the home for a patient with ALS.)

Provide appropriate education to the patient and his family before discharge. (See Teaching the patient with ALS.)

MUSCULAR DYSTROPHY

Muscular dystrophy is a group of congenital neuromuscular disorders characterized by progressive symmetrical wasting of skeletal muscles without neural or sensory defects. Paradoxically, these wasted muscles tend to enlarge because of connective tissue and fat deposits, giving an erroneous impression of muscle strength. The main types of muscular dystrophy are Duchenne’s (DMD) (pseudohypertrophic), Becker’s (BMD) (benign pseudohypertrophic), Landouzy-Dejerine (facioscapulohumeral), and Erb’s (limb-girdle) dystrophy.

The prognosis varies. DMD generally strikes during early childhood and usually results in death by age 20. Patients with BMD typically live into their 40s. Patients with Landouzy-Dejerine and Erb’s dystrophies usually aren’t adversely affected and may live long, healthy lives.

Pathophysiology

The absence or severe reduction of dystrophin protein results in a series of events that lead to myonecrosis with fibrin splitting. Phagocytosis of the muscle cells by inflammatory cells causes scarring and loss of muscle function. As the disease progresses, skeletal muscle becomes almost totally replaced by fat and connective tissue. The skeleton eventually becomes deformed, causing progressive immobility. Cardiac, smooth, and skeletal muscles are affected.

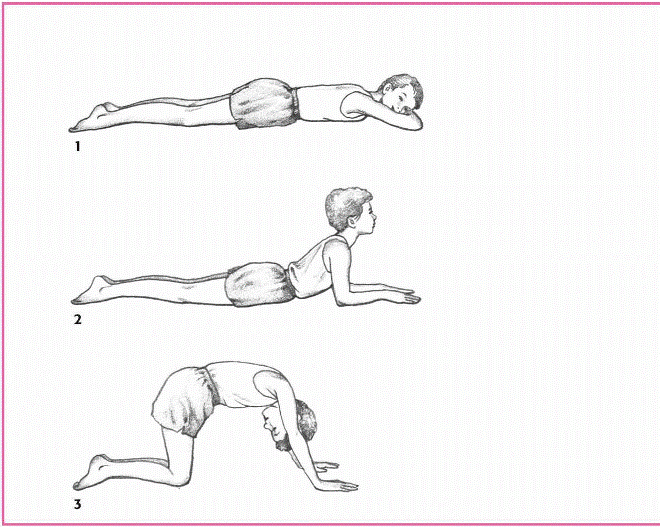

OBSERVING GOWERS’ SIGN

Because Duchenne’s and Becker’s muscular dystrophies weaken pelvic and lower extremity muscles, the patient must use his upper body to maneuver from a prone to an upright position, a maneuver called Gowers’ sign.

|

|

Lying on his stomach with his arms stretched in front of him, the patient raises his head, backs into a crawling position, and then into a half-kneel.

Then stooping, he braces his legs with his hands at the ankles and walks his hands (one after the other) up his legs until he pushes himself upright.

Complications

Crippling disability

Contractures

Pneumonia

Arrhythmias

Cardiac hypertrophy

Assessment findings

DMD AND BMD

Wide stance and waddling gait

Gowers’ sign when rising from a sitting position (see Observing Gowers’ sign)

Muscle hypertrophy and atrophy

Enlarged calves

Poor posture

Lordosis with abdominal protrusion

Scapular “winging” or flaring when raising arms

Contractures

Tachypnea and shortness of breath

LANDOUZY-DEJERINE DYSTROPHY

Pendulous lower lip

Possible disappearance of nasolabial fold

Diffuse facial flattening leading to a masklike expression

Inability to suckle (infants)

Scapulae with a winglike appearance; inability to raise arms above head (see Detecting muscular dystrophy)

ERB’S DYSTROPHY

Muscle weakness

Muscle wasting

Scapulae with a winglike appearance; inability to raise arms above head

Lordosis with abdominal protrusion

Waddling gait

Poor balance

Diagnostic test results

Electromyography typically demonstrates short, weak bursts of electrical activity or high-frequency, repetitive waxing and waning discharges in affected muscles.

Muscle biopsy shows variations in the size of muscle fibers and, in later stages, shows fat and connective tissue deposits; dystrophin is absent in DMD and diminished in BMD.

Serum creatine kinase is markedly elevated in DMD, but only moderately elevated in BMD and Landouzy-Dejerine dystrophy.

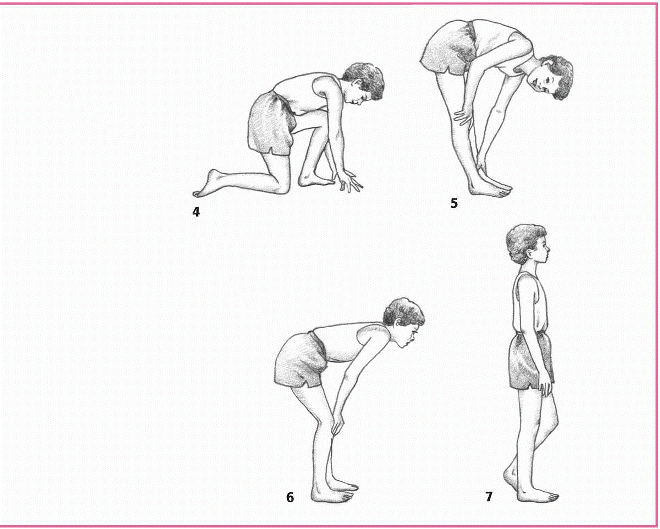

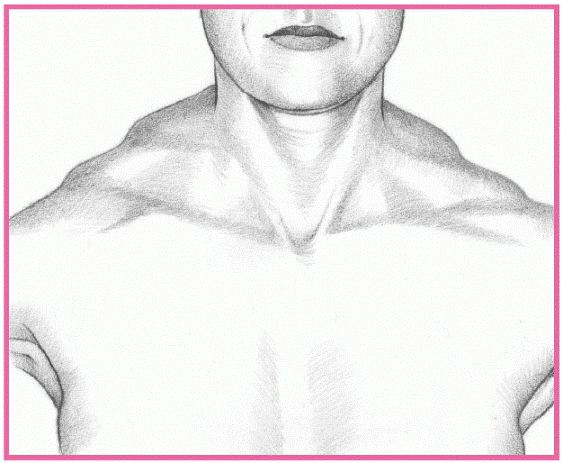

DETECTING MUSCULAR DYSTROPHY

In muscular dystrophy, the trapezius muscle typically rises, creating a stepped appearance at the shoulder’s point.

|

From the posterior view, the scapulae ride over the lateral thoracic region, giving them a winged appearance. In Duchenne’s and Becker’s dystrophies, this winglike sign appears when the patient raises his arms. In other dystrophies, the sign is obvious without arm raising. (In fact, the patient can’t raise his arms.)

|

Immunologic and molecular biological assays available in specialized medical centers facilitate accurate prenatal and postnatal diagnosis of DMD and BMB. These assays are replacing muscle biopsy and elevated serum creatine kinase levels in diagnosing these dystrophies. They can also help to identify carriers.

Treatment

No treatment stops the progressive muscle impairment of muscular dystrophy. However, orthopedic appliances, exercise,

physical therapy, and surgery to correct contractures can help preserve the patient’s mobility and independence. Prednisone improves muscle strength in patients with DMD.

physical therapy, and surgery to correct contractures can help preserve the patient’s mobility and independence. Prednisone improves muscle strength in patients with DMD.

DISCHARGE TEACHING

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH MUSCULAR DYSTROPHY

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH MUSCULAR DYSTROPHYBefore discharge, teach the patient and his family:

about the disorder and its implications

about treatment options, such as surgery and therapy

about prescribed medication administration, dosage, possible adverse effects, and when to notify the physician

the importance of a nutritious diet low in calories and high in protein and fiber

the need for increased fluid intake

range-of-motion exercises to improve muscle tonicity and the importance of avoiding prolonged immobility

types of therapy that would be beneficial, such as physical and occupational therapy

signs and symptoms of complications

methods to promote the patient’s independence

the importance of follow-up care

the benefits of utilizing available community support groups such as the local chapter of the Muscular Dystrophy Association.

Nursing interventions

Encourage coughing, deep-breathing exercises, and diaphragmatic breathing.

Encourage and assist with active and passive range-of-motion exercises.

Advise the patient to avoid long periods of bed rest and inactivity.

Provide trapeze bars, overhead slings, and a wheelchair to assist mobility.

Encourage adequate fluid intake and provide a low-calorie, high-protein, high-fiber diet.

Provide emotional support to the patient and his family.

Provide appropriate education to the patient and his family before discharge. (See Teaching the patient with muscular dystrophy.)