CHAPTER 10

Neuromuscular Disorders

I. General Evaluation

A. History

1. Chief complaint

a. Weakness/motor versus sensory

b. Acute versus subacute versus chronic

c. Symmetric versus asymmetric

2. Contributing history

a. Family history

b. Medications, toxins

c. Trauma

d. Infections

e. Vaccinations

f. Diet

g. Concurrent medical conditions (i.e., autoimmune, rheumatologic, endocrinopathies, cardiovascular)

3. Neurophysiologic/electrodiagnostic studies (see Chapter 17)

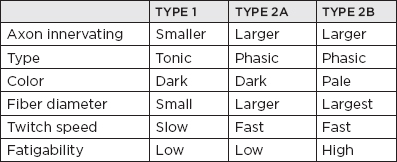

B. Types of muscle fibers

C. Electromyography (EMG) of neuropathic, neuromuscular junction, and myopathic processes

| MUPs | RECRUITMENT |

Myopathy | Low amplitude, short duration, polyphasic | “Early” pattern |

Neuromuscular junction disorder | Motor unit instability; possibly low amplitude, short duration, polyphasic (when severe) | Normal (typically) |

Denervation (with reinnervation from collateral sprouting of intact axons) | High amplitude, long duration (and polyphasia, marked in early chronic stage) | Decreased |

Denervation with reinnervation (with no intact axons for collateral sprouting) | l = low amplitude, short duration, polyphasic in EARLY stages of reinnervation (“nascent units”) | Decreased (without “early” pattern) |

Abbreviation: MUPs, motor unit potentials.

D. Pathologic differentiation between myopathic and neurogenic processes

MYOPATHIC | NEUROGENIC |

Marked irregularity of fiber size | Nests of atrophic fibers |

Rounded fibers | Angular fibers |

Real increase in number of muscle nuclei | Pseudo-increase of nuclei due to cytoplasmic atrophy |

Centralized nuclei | Centralized nuclei not present |

Necrotic and basophilic fibers | Necrotic and basophilic fibers not present |

Cytoplasmic alterations | Target fibers |

Copious interstitial fibrosis at times | Minimal interstitial fibrosis |

Inflammatory cellular infiltrate (with myositis) | Inflammatory cellular infiltrate not present |

II. Peripheral Neuropathic Syndromes

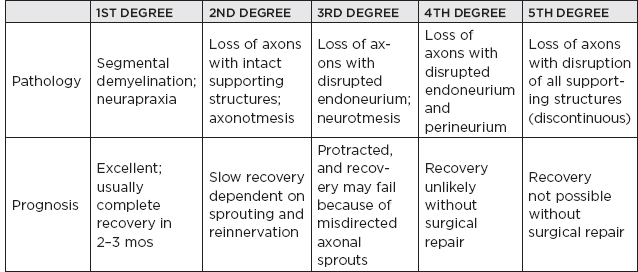

A. Classification and degrees of peripheral nerve injury

1. Segmental demyelination

a. Conduction block

b. Segmental conduction velocity slowing

c. Temporal dispersion

d. Prolongation of distal latencies

e. Normal compound muscle action potential (CMAP) and sensory nerve action potential (SNAP) at DISTAL stimulation sites.

2. Neurapraxia: localized conduction loss along a nerve without axon loss, caused by a focal lesion, typically demyelinating in nature, and followed by a relatively rapid and complete recovery

3. Axonotmesis: nerve injury characterized by disruption of the axon and myelin sheath but with sparing of the connective tissue components, resulting in degeneration of the axon distal to the site of damage; regeneration of the axon is typically successful, with good functional recovery.

4. Wallerian degeneration: (e.g., for L5–S1 radiculopathy) complete in 10 to 14 days for nerves supplying proximal areas such as paraspinal muscles and up to 5 to 6 weeks in the distal leg and foot muscles.

B. Mononeuropathies

1. Sciatic mononeuropathy

a. Common causes

i. Hip replacement/fracture/dislocation

ii. Femur fracture

iii. Acute compression (coma, drug overdose, intensive care unit [ICU], prolonged sitting)

iv. Gunshot or knife wound

v. Infarction (vasculitis, iliac artery occlusion, arterial bypass surgery)

vi. Gluteal contusion or compartmental syndrome (during anticoagulation)

vii. Gluteal injection or compartment syndrome

viii. Endometriosis (catamenial sciatica)

NB:

NB:

The sciatic nerve is composed of a peroneal division and tibial division. The only muscle above the knee supplied by the peroneal division is the short head of the biceps femoris.

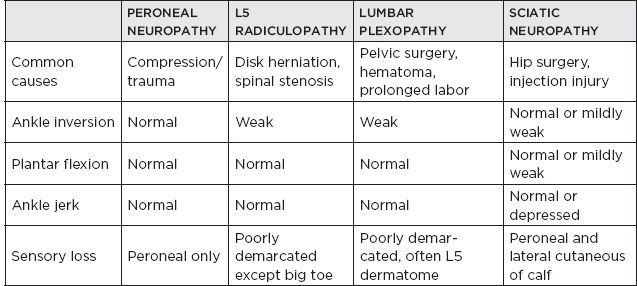

2. Footdrop

a. Common causes

i. Deep peroneal mononeuropathy

ii. Common peroneal mononeuropathy

iii. Sciatic mononeuropathy

iv. Lumbosacral plexopathy (especially of the lumbosacral trunk)

v. Lumbar radiculopathy (L5 or, less commonly, L4)

vi. Motor neuron disease/spinal cord lesion

vii. Parasagittal cortical or subcortical cerebral lesion

NB:

NB:

To differentiate a peroneal nerve lesion from an L5 lesion in a patient with a footdrop, test the foot invertors. Peroneal nerve lesions should not involve the foot invertors. Foot evertors will be involved with damage to the superficial peroneal nerve. The majority of the peroneal palsies occur at the level of the fibular head.

Clinical Assessment of Footdrop

3. Piriformis syndrome

a. Clinically: buttock and leg pain worse during sitting without low back pain; exacerbated by internal rotation or abduction and external rotation of the hip; local tenderness in the buttock; soft or no neurologic signs

b. EMG/nerve conduction studies (NCS): denervation seen in branches after the piriformis muscle, but normal in branches before the piriformis muscle

4. Femoral mononeuropathy

a. Clinically: acute thigh and knee extension weakness; numbness of anterior thigh; absent knee jerk; normal thigh adduction

b. Common causes

i. Compression in the pelvis: retractor blade during pelvic surgery (iatrogenic), abdominal hysterectomy, radical prostatectomy, renal transplantation, and so forth; iliacus or psoas retroperitoneal hematoma; pelvic mass

ii. Compression in the inguinal region: inguinal ligament during lithotomy position (vaginal delivery, laparoscopy, vaginal hysterectomy, urologic procedures); inguinal hematoma; during total hip replacement; inguinal mass

iii. Stretch injury (hyperextension)

iv. Others: radiation; laceration; injection

NB:

NB:

The pain in femoral mononeuropathy due to psoas hematoma is markedly worse with forced hyperextension of the hip (stretches the psoas muscle).

5. Tarsal tunnel syndrome: compression of the tibial nerve or any of its three branches under the flexor retinaculum

a. Clinically: sensory impairment in the sole of the foot; Tinel’s sign; muscle atrophy of the sole of the foot; rarely weak (long toe flexors are intact); ankle reflexes normal; sensation of the dorsum of the foot normal; note: not associated with footdrop

NB:

NB:

Nocturnal pain is common, such as in carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS). There is an anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome caused by compression of the deep peroneal nerve at the ankle that results in paresis of the extensor digitorum brevis alone.

b. Differential diagnosis

i. Plantar fasciitis

ii. Stress fracture

iii. Arthritis

iv. Bursitis

v. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy

vi. High tibial or sciatic mononeuropathy

vii. Sacral radiculopathy

viii. Peripheral neuropathy

6. Meralgia paresthetica

a. Anatomy

i. Entrapment of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, which is a pure sensory branch via L2 and L3 nerve roots

ii. Enters through the opening between the inguinal ligament and its attachment to the anterior superior iliac spine

b. Etiologies

i. Obesity

ii. Wearing tight belt or girdle

iii. Pregnancy

iv. Prolonged sitting

v. More common in diabetics

vi. Abdominal or pelvic mass

vii. Metabolic neuropathies

c. Clinical: burning paresthesia in the anterolateral aspect of the upper thigh just above the knee; may be exacerbated by clothing contact; may improve with massage; bilateral in 20% of cases

d. Differential diagnosis

i. Femoral neuropathy

ii. L2 or L3 radiculopathy

iii. Nerve compression by abdominal or pelvic tumor

e. Treatment: usually spontaneous improvement; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for 7 to 10 days for pain; avoid tight pants/belts; use suspenders, if able

7. Ulnar nerve mononeuropathy

a. Localization of ulnar neuropathy

i. Guyon’s canal (wrist) entrapment: sensory loss of the palmar surface of the little and ring fingers and the ulnar side of the hand

ii. Sensory loss of medial half of the ring finger that spares the lateral half (pathognomonic of ulnar nerve lesion; not seen in lower trunk or C8 root lesion)

iii. If flexor carpi ulnaris and flexor digitorum profundus are both abnormal with axonal loss features, the lesions are localized at or proximal to the elbow.

iv. Purely axonal lesions with normal flexor carpi ulnaris and flexor digitorum profundus suggest lesions at the distal forearm or wrist.

v. Ulnar entrapment syndromes at the elbow

(A) Cubital tunnel syndrome: proximal edge of the flexor carpi ulnaris aponeurosis (arcuate ligament)

(B) Subluxation of the ulnar nerve at the ulnar groove: often caused by repetitive trauma

(C) Tardy ulnar palsy: may occur years after a distal humeral fracture in association with a valgus deformity

(D) Idiopathic ulnar neuropathy at the elbow

(E) Other causes of compressive ulnar neuropathy at the elbow: pressure; bony deformities; chronic subluxation

vi. Martin-Gruber anastomosis: patients with apparent conduction block of the ulnar motor fibers at the elbow should undergo further investigation to rule out the presence of anomalous nerves (Martin-Gruber anastomosis), which occur in 20% to 25% of the normal population. This is an anatomical variant in which branches cross over from the median to the ulnar nerve in forearm.

b. Clinical signs of ulnar neuropathy: Tinel’s sign at the elbow; sensory exam may be normal despite symptoms; ulnar claw hand (caused by weakness or by flexion of the interphalangeal joints of the 3rd and 4th lumbricals); Froment’s sign; when the patient is asked to adduct the thumb in a pincer-type grip (such as grasping a sheet of paper), there will be hyperflexion of the thumb interphalangeal (IP) joint (flexor pollicis longus, median innervated) to compensate for loss of the ulnar-dependent adductor strength.

NB:

NB:

Ulnar nerve lesions do not typically cause sensory symptoms proximal to the wrist. If such symptoms are present, consider a proximal lesion (e.g., root or plexus).

LESION SITE | NERVE AFFECTED | CLINICAL |

Guyon’s canal | Main trunk of ulnar nerve | Ulnar palmar sensory loss and weakness of all ulnar intrinsic hand muscles |

Ulnar cutaneous branch | Ulnar palmar sensory loss only | |

Pisohamate hiatus NB: Pure motor lesion! | Deep palmar branch (distal to branch to the abductor digiti minimi) | Weakness of ulnar intrinsic hand muscles with sparing of the hypothenar muscles and without sensory loss |

Midpalm (rare) | Deep palmar branch (distal to hypothenar) | Weakness of adductor pollicis, the 1st, 2nd, and possibly the 3rd interossei only, sparing the 4th interossei and hypothenar muscles, without sensory loss |

8. Radial nerve mononeuropathy

a. Anatomy

i. Arises from posterior divisions of three trunks of the brachial plexus

ii. Receives contribution from C5 to C8

iii. Winds laterally along spiral groove of the humerus

iv. Distinguished from brachial plexus posterior cord injury by sparing deltoid (axillary nerve) and latissimus dorsi (thoracodorsal nerve)

b. Etiologies and localization

i. Spiral groove (most common)

ii. Saturday night palsy: acute compression at the spiral groove

iii. Humeral fracture

iv. Strenuous muscular effort

v. Injection injury

vi. Trauma

c. Clinical

i. Axillary compression: less common than compression in the upper arm; etiologies: secondary to misuse of crutches or during drunken sleep; clinical: weakness of triceps and more distal muscles innervated by radial nerve

ii. Mid–upper-arm compression: site of compression: spiral groove, intermuscular septum, or just distal to this site; etiologies: Saturday night palsy, under general anesthesia; clinical: weakness of wrist extensors (wristdrop) and finger extensors; triceps normal

iii. Forearm compression: radial nerve enters anterior compartment of the arm above the elbow and gives branches to brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus before dividing into posterior interosseous nerve and the superficial radial nerve; the posterior interosseous nerve goes through the supinator muscle via the arcade of Frohse (fibrous band between the two heads of the supinator muscle).

NB:

NB:

The posterior interosseous nerve is purely motor. A lesion results in fingerdrop. The superficial radial nerve is mainly sensory.

(A) Posterior interosseous neuropathy

(1) Etiologies: lipomas, ganglia, fibromas, rheumatoid disease

(2) Clinical: extensor weakness of thumb and fingers (fingerdrop)—distinguished from radial nerve palsy by less to no wrist extensor weakness; no sensory loss.

NB:

NB:

Posterior interosseous syndrome spares the supinator, which receives innervation proximal to the site of compression.

(B) Radial tunnel syndrome (supinator tunnel syndrome)

(1) Contains radial nerve and its two main branches, including posterior interosseous nerve and superficial radial nerve

(2) Etiologies: mass lesion, local edema, inflammation (including that of the supinator muscle), hand/wrist overuse through repetitive movements, blunt trauma to the proximal forearm

(3) Clinical: pain in the region of common extensor origin at the lateral epicondyle (mimicking “tennis elbow”); tingling in distribution of superficial radial nerve; usually no weakness

NB:

NB:

Cheiralgia paresthetica (Wartenburg syndrome) is a pure sensory syndrome caused by lesion of the superficial cutaneous branch of the radial nerve in the forearm. It causes paresthesia and sensory loss/disturbance in the radial part of the dorsum of the hand and the dorsal aspect of the thumb and index fingers.

9. Median nerve entrapment

a. The two most common sites of entrapment of the median nerve: transverse carpal ligament at the wrist (carpal tunnel syndrome; CTS); and upper forearm by pronator teres muscle (pronator teres syndrome)

b. Anatomy

i. Contribution from C5 to T1 (but mostly C8–T1).

ii. In the upper forearm, it passes through the pronator teres, supplying this muscle, and then branches to form the purely motor anterior interosseous nerve (AIN), which supplies the lateral half of flexor digitorum profundus, flexor pollicis longus, and pronator quadratus; it emerges from the lateral edge of the flexor digitorum superficialis and later passes under the transverse carpal ligament.

iii. The transverse carpal ligament attaches medially to the pisiform and hamate.

iv. The palmar cutaneous branch arises from the radial aspect of the nerve proximal to the transverse carpal ligament and crosses over the ligament to provide sensory innervation to the base of the thenar eminence.

c. Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS)

i. Etiologies

(A) Trauma: repetitive movement; repetitive forceful grasping or pinching; awkward positioning of hand or wrist; direct pressure over carpal tunnel; use of vibrating tools

(B) Systemic conditions: obesity; diabetes mellitus; pregnancy; hypothyroidism; amyloidosis; mucopolysaccharidosis V; tuberculous tenosynovitis

(C) Other: dialysis shunts

ii. Differential diagnosis

(A) Cervical radiculopathy, especially C6/C7

(B) Neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome: sensory manifestations are in C8/T1 distribution but motor deficits are typically in the thenar eminence.

(C) Peripheral polyneuropathy: manifestations in the distal lower limbs; hyporeflexia/areflexia

(D) High median mononeuropathy: for example, pronator syndrome, compression at the ligament of Struthers in the distal arm; will have weakness in the lateral long finger flexors

(E) Cervical myelopathy

iii. Clinical

(A) Paresthesias with numb hand that may awaken patient at night: palm side of lateral 3½ fingers, including thumb, index, middle, and lateral half of ring finger; dorsal side of the same fingers distal to the proximal interphalangeal joint; radial half of palm

(B) Weakness of hand: particularly thumb abduction

(C) Phalen’s test: 30 to 60 seconds of complete wrist flexion reproduces pain in 80% of cases.

(D) Tinel’s sign: paresthesia or pain in median nerve distribution produced by tapping carpal tunnel in 60% of cases

(E) Shake sign: patients show that they shake out their hands at night when they fall asleep.

iv. EMG/NCS

(A) The electrophysiologic hallmark of CTS is focal slowing of conduction at the wrist.

(B) Normal in ~15% of cases of CTS (sensitivity increases by obtaining palmar mixed nerve responses)

(C) Sensory latencies are more sensitive than motor latencies.

v. Lab testing (informed by clinical suspicion)

(A) Fasting blood glucose, 2 hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), HbA1C (diabetes)

(B) Thyroid function tests (TFTs) (thyroid disease/myxedema)

(C) Complete blood count, serum immunofixation (monoclonal gammopathy)

vi. Treatment

(A) Nonsurgical: rest; neutral position wrist splint at nights; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; local steroid injection

(B) Surgical: carpal tunnel release

(C) Short-term low dose oral steroids

d. Pronator teres syndrome

i. Etiologies: direct trauma; repeated pronation with tight handgrip

ii. Nerve entrapment between two heads of pronator teres

iii. Clinical: vague aching and fatigue of forearm with weak grip; not exacerbated during sleep; pain in palm distinguishes this from CTS because median palmar cutaneous branch transverses over the transverse carpal ligament

C. Radiculopathies

1. Clinical

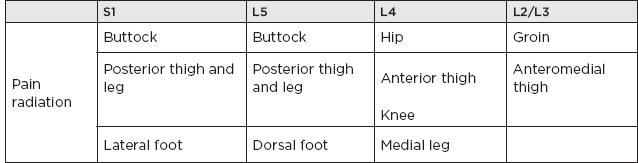

a. Lumbosacral radiculopathy

i. L5 radiculopathy: most common radiculopathy

Clinical Presentations in Lumbosacral Radiculopathy

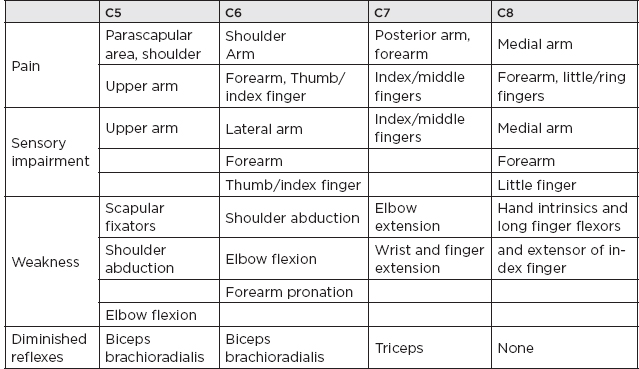

b. Cervical radiculopathies

Clinical Presentations in Cervical Radiculopathy

2. Differential diagnosis of radiculopathies

a. Congenital

i. Meningeal cyst

ii. Conjoined nerve root

b. Acquired/degenerative

i. Spinal stenosis

ii. Spondylosis

iii. Spondylolisthesis

iv. Ganglion cyst of facet joint

c. Infectious

i. Diskitis

ii. Lyme disease, other inflammatory syndromes

d. Neoplastic

e. Vascular (including that seen in diabetic amyotrophy)

f. Referred pain syndromes

i. Kidney infection

ii. Nephrolithiasis

iii. Cholelithiasis

iv. Appendicitis

v. Endometriosis

vi. Pyriformis syndrome

3. Electrodiagnostic studies in radiculopathies

a. Needle EMG: the most sensitive electrodiagnostic test for diagnosis of radiculopathy in general

b. Goals of EMG in radiculopathy: confirm root involvement; exclude more distal lesion; localize the lesion to either a single root or multiple roots; assess severity of injury; assess whether chronic and/or active denervation.

c. Differential diagnosis of lumbosacral plexopathy versus lumbosacral radiculopathy—depends on electrodiagnostic findings, for example: needle exam of paraspinal muscles → abnormal in radiculopathy; SNAP → abnormal in plexopathy