Figure 11.1. Extracranial (brachial plexus, N9, and cervical spinal, N13, potentials), intracranial lemniscus (P14), and intracortical (N20-P25) SEP components.

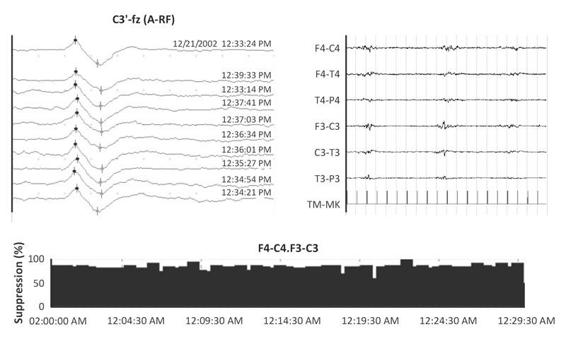

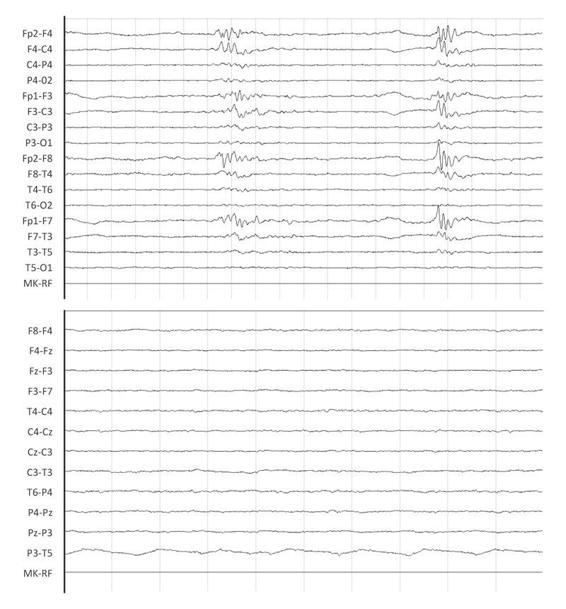

This information is very useful in the neurocritical patient, who is often poorly clinically evaluable because of pharmacological sedation, curarization, or the severity of coma itself. SEPs have the additional advantage of being resistant to anesthetics, having a waveform easily interpretable and comparable at subsequent tests (Figure 11.2).

Figure 11.2. During a continuous infusion of thiopental sodium (TPS), with a suppression of about 90%, which precludes EEG evaluation for clinical purposes, the early components of SEPs are well measurable in their latency and amplitude parameters.

Because we believe that a reason for the underuse of SEPs in the ICU is due to major technical difficulties of recording in that environment and the perceived lower reliability of the test result, more precise technical information is necessary about their recording. First, it is necessary that the neuropathophysiology technician and the neurophysiologist have experience in recording and interpretation of evoked potentials in the laboratory for neurological diagnosis, in addition to specific training in the intensive care field. It is also necessary that the technician communicates the problems encountered during the examination: obstacles to stimulation in conventional locations; excessive environmental artifacts or patient-related artifacts; and the need to perform sedation or curarization to optimize the recording.

Intradermal needle electrodes or silver chloride cup electrodes are used, possibly braided to reduce artifacts.

The recording apparatus for SEPs should have at least 2 channels (4 recommended). For full specifications on amplifiers and averaging and electrical safety, please refer to the guidelines reported in Suppl. 8 of Muscle and Nerve, 1999 (S123-138).

We want to stress the importance of some methodological aspects:

- Stimulus frequency: 3-5 Hz; analysis time: 50 or 100 ms (with the lowest frequency of stimulation and the greater analysis time also intermediate-latency intracortical components subsequent to N20-P25 are more identifiable; analysis time of 100 ms is therefore necessary to determine the absence of any cortical response).

- Number of mediated responses: 200-400, depending on recording conditions (signal-to-noise ratio) and identifiable components. At least two sets of repeatable responses must be obtained. It is advisable to obtain a larger number of repeatable series when altered patterns of clinical relevance are detected (absence of cortical SEP).

- Stimulus intensity: in cases of curarization the evaluation of response width from Erb’s point or cortical allows to verify that the stimulus intensity is supramaximal.

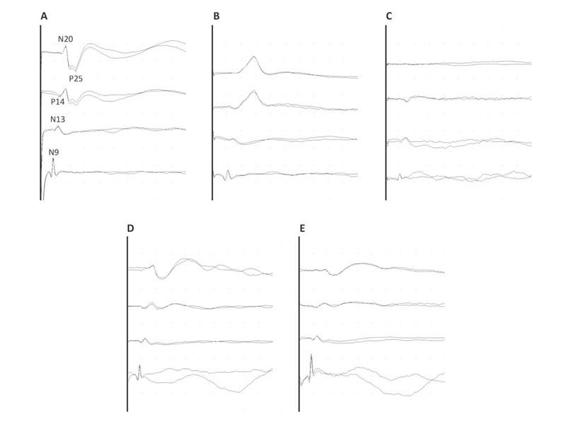

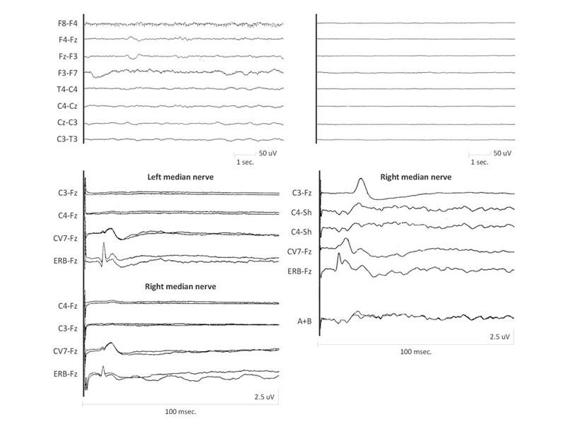

To record SEPs with median nerve stimulation the electrodes are placed at Erb’s point (contralateral Erb), at the spinous process Cv7 (referred to antecollis) and C3’-C4’ (referring to Fz and the ipsilateral mastoid) (Figure 11.3). A non-cephalic reference can be used, but this creates more artifacts. We also suggest the use of the Fz reference because, even though the latter produces a greater variability of interindividual width, it prevents the influence of subcortical potentials and reduces the interference contamination. In addition, the Fz reference allows the recognition of cortical responses even when their presence is questionable considering only the tracks with mastoid reference.

Figure 11.3. Example of SEP classification. (A). Normal SEP. (B). Pathological SEP because of an increase in the transmission time. (C). Absent cortical SEP, considering both Fz and mastoid reference. (D) and (E). Pathological width asymmetry (>50%) of the cortical SEP between the two hemispheres with normal transmission time [4].

It is also important to establish the criteria for SEPs abnormality (Figure 11.3):

- Absence of mandatory components (N9 in an ipsicontralateral derivation from Erb’s point, N20 in a derivation with Fz reference, P14 in a derivation with auricular or mastoid reference, N13 in a derivation with AC reference) (Figure 11.3C). This criterion implies that there must be adequate technical conditions to identify a component if present. Sometimes not being able to replicate some of the responses (especially spinal and subcortical) in the presence of excessive artifacts is a technical limitation rather than an abnormality of the patient.

- Extension of interpeak latencies (N9-N13, N13-N20 and P14-N20). Generally, reference is made to the limits of 2.5-3.0 standard deviation (SD) of average values for each laboratory (Figure 11.3B). The problem of not having homogeneous normative data for patients in the ICU must be considered. In addition, many non-pathological factors can interfere with the interpeak latencies (temperature, therapy, etc.).

- Asymmetries. In the absence of a change in latency, a variation in the width should be viewed with caution, given the high variability in normal subjects for both absolute values and the interside asymmetry itself (Figure 11.3D-E). However, we consider it useful for the N20 cortical component to accept as pathological a reduction in width of more than 50% of the contralateral.

The EEG and the EPs can be used for both diagnosis/prognosis and monitoring the evolution of brain damage or the occurrence of secondary damage. Discontinuous evaluation is sufficient for the former, while continuous neurophysiological evaluation is required for the latter in oder to obtain more detailed clinical data.

11.3.1 Using EEG and EP for Diagnostic and Prognostic Purposes

Diagnosis

Although EEG is underused in coma [5], its diagnostic utility is confirmed in clinical practice for differential diagnosis at the bedside (metabolic, infectious, drug, and epileptic causes).

EEG is the best available method to diagnose epileptic activity: the increased use of EEG and continuous EEG (CEEG) in the ICU has revealed a surprisingly high incidence (8-28%) of non-convulsive seizures and non-convulsive status epilepticus in patients with acute brain damage [6]. EEG is the only method available to diagnose such conditions and to guide their treatment. Young [5] proposed the most commonly followed primary and secondary diagnostic criteria. These criteria have been recently reviewed by Chong and Hirsch [7].

EEG is useful for the differential diagnosis of motor manifestations in ICU patients who may have a wide variety of non-epileptic involuntary and semi-voluntary movements such as tremors, spasms, tetanic spasms, septic rigor, stiffness due to neuroleptics, extrapyramidal movements, ischemic tremors, tonic head and eye deviations, and abnormal posturing.

Besides providing indications on the etiopathogenesis of coma (when it is not known), EEG findings may also be diagnostic of the effective state of consciousness. Its contribution is decisive in determining the depth of coma beyond the clinical evidence and highlighting the discrepancy between the apparent clinical status and the effective depth of the consciousness disturbance in particular conditions (traumatic and vascular locked-in states, neuromyopathy in critically ill patients, frontal syndrome or associations thereof).

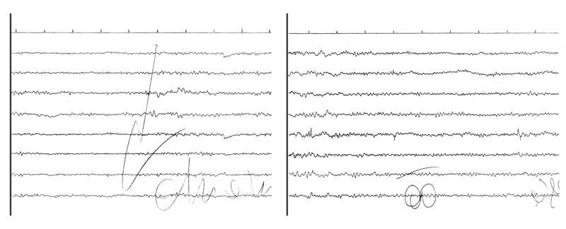

Considering only the motor responses, in the absence of an EEG, it is very difficult to determine the real consciousness disturbance in these conditions [1,8]. Logically, the EEG data must be integrated with neuroimaging and other neurophysiological tests. The presence and/or duration of coma may be overestimated considering the clinical evaluation alone (Figure 11.4).

Figure 11.4. Locked-in due to a ventral pons-midbrain ischemic lesion. The left tracing shows passive eye opening with a slight desynchronization of alpha rhythm. The right tracing shows how the acoustic stimulus generates a “paradoxical” alpha rhythm. The presence of a reactive alpha rhythm confirms the diagnosis of locked-in.

Furthermore, EEG is one of the tests to confirm the diagnosis of brain death in some countries [9]. It is should be noted that the short-latency EP, and SEPs in particular, are considered by some authors to be very useful for the diagnosis of brain death when “confounding” factors are present, as in drug neurosedation, which invalidate and render the clinical criteria alone and EEG insufficient.

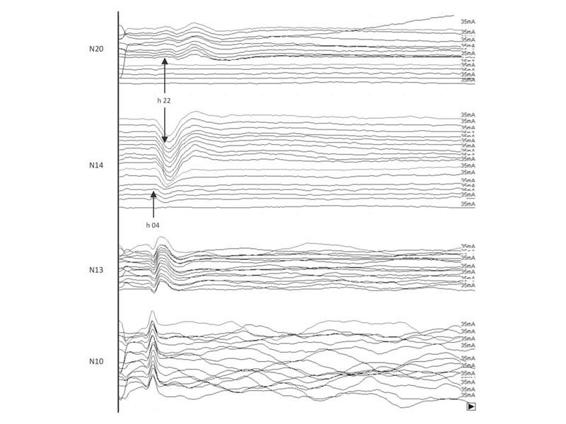

Changes in SEPs reliably reflect the rostrocaudal deterioration of brain damage until brain death, with loss, first, of intracortical components, and then of the caudal lemniscus component (P14), which reflects bulbar generator activity. The loss of all intracranial components (N20 and P14), when first recorded, associated with conservation of extracranial components (N13, N10) is the SEPs pattern of brain death (Figure 11.5).

As indicated in European guidelines [2], the short latency EP improve the timeliness, safety and the reliability of the diagnosis of brain death, especially when this cannot be made using conventional criteria.

Figure 11.5. Post-traumatic coma: rostrocaudal deterioration in a patient who could not be evaluated clinically or by EEG because he/she was under profound neurosedation (thiopental sodium infusion) until the night before. At 22 h the N20 intracortical component disappeared; 6 hours later, with the disappearance of the P14 bulbar component, the SEP pattern of brain death (extracranial components unchanged) is evident. Transcranial Doppler (TCD) performed 2 hours later confirmed the absence of intracranial blood flow.

Prognosis

A systematic review of EEG scales for the classification of coma severity [5,10,11,12,13,14] is beyond the scope of this chapter. Suffice it to state that all these classifications are based on the assessment of the background activity, the presence of reactivity and variability, and the detection of special patterns.

The Synek’s classification (1988, 1990) [13,15] divides into three categories with different prognostic significance (favourable, uncertain, unfavourable) the EEG patterns most frequently found in post-traumatic coma and hypoxic-ischemic coma (Table 11.1).

Favourable significance | Uncertain significance | Unfavourable significance |

Grade 1 | Grade 2, non-reactive | Low amplitude, grade 3 |

Grade 2, reactive | Grade 3, diffuse delta non-reactive/(reactive) | Burst-suppression, grade 4 |

Epileptiform discharges, grade 4 | ||

Low output, grade 4 | ||

Isoelectric, grade 5 | ||

Spindle pattern coma, grade 3 | Epileptiform discharges, grade 3 | Alpha pattern coma, non-reactive |

Frontal rhythmic delta reactive/non-reactive | Alpha coma, reactive | Theta pattern coma |

BIPLEDs, PEDs |

Table 11.1. Synek’s classification of prognostic categories of EEG patterns in post-traumatic and hypoxic-ischemic coma. [13].

It is useful to briefly mention the epidemiology of the two different types of coma. The first generally has a poor prognosis on awakening, as 70-80% of patients experience death or a vegetative state. In the second type about 60% of patients awaken, with 30% mortality (the latter mostly early). Therefore, in the first type the early prognosis of unfavourable outcome will be more important, while in the second, in addition to the recovery of a state of consciousness, the early prognosis of residual disability will be very useful.

11.3.2 Hypoxic-ischemic Coma

It should be noted that EEG is more useful in the prognosis of hypoxic-ischemic coma, as the frequency of special or low voltage patterns falling in the category with a poor prognosis is very high for this type of coma. It proves less useful in the post-traumatic phase, when the most frequent EEG pattern is characterized by irregular, often non-reactive dominant medium voltage delta, belonging to the class of uncertain prognostic significance (Figure 11.6).

Figure 11.6. EEG burst suppression pattern (left tracing) at 24 hours in hypoxic-ischemic coma (Glasgow Coma Scale score [GCS] = 4), which at 48 hours is transformed into low voltage pattern (right tracing).

When preparing to make an early prognosis of hypoxic-ischemic coma, we must consider at least six meta-analyses on the evidence of the usefulness of short-latency EP and in particular of SEPs [16,17,18,19]. All studies agree in indicating that the bilateral absence of cortical SEP has 100% adverse prognostic significance (all patients die or remain in a vegetative state). Zandbergen et al. [16] proposed “clinical” guidelines for the prognosis of unfavourable outcome of hypoxic-ischemic coma, postponing the prognostic assessment to 72 hours and limiting SEPs recording in patients with absent photomotor or with M 1-3/GCS. A proposal for European guidelines on the use of neurophysiological tests in the ICU recommends an evaluation already at 24 hours [2]. A report by the American Academy of Neurology found the SEPs among the most reliable prognostic tests in hypoxic-ischemic coma [20], but does not include EEG for which there is less evidence in the literature. We believe instead that the two tests complement each other, and albeit infrequently, EEG can provide information on unfavourable outcome not obtainable with SEPs alone (Figure 11.7).

Figure 11.7. (A). EEG recording of theta delta non-reactive activity and a SEP pattern absent in both hemispheres. (B). Low-voltage EEG/absence of cortical electrical activity and SEPs bilaterally present, albeit simplified.

In our hospital we have implemented an EEG-SEP protocol agreed upon with interventional cardiologists and the general intensive care unit for the early prognosis of hypoxic-ischemic coma. The protocol includes an EEG-SEP recording at 24 hours in a patient with a motor GCS ≤3: in EEG-SEP patterns unfavourable for the recovery of consciousness (bilateral absence of SEPs, severe EEG abnormalities), given the clinical importance of this finding, we perform a confirmatory test at 48-72 hours.

The clinical usefulness of early prognosis is, in case of negative patterns, that it discourages aggressive interventions for hemodynamics in severely unstable patients, informs the family early on outcome and refers patients to low-intensity rehabilitation facilities after discharge from the ICU.

11.3.3 Post-traumatic Coma

As mentioned, EEG and GCS itself are less reliable as early prognostic indicators in post-traumatic coma compared with hypoxic-ischemic coma [21]. Neurosedation in the early stage hinders clinical evaluation of the patient and makes the underlying EEG activity and reactivity less interpretable. Early SEPs do not have these limitations and are sensitive only to structural damage. A meta-analysis by Robinson et al [18] not only confirms the highly unfavourable prognostic value of absent SEP patterns in post-traumatic coma (90-95% of non-“awakening” in bilateral absence of SEPs) but also highlights the favourable prognostic significance of the normal pattern SEP (over 90% of “awakening” in bilaterally normal SEPs).

By classifying the pattern of SEP alterations in both hemispheres (Figure 11.3) it is possible to group the changes into three categories with different prognostic significance: Grade 1 [(NN, NP): normal] with favourable prognosis; Grade 3 [(AA): absent] with poor prognosis; and Grade 2 [(NA, PP, AA): preserved] with uncertain prognosis. It should be noted that grades 1 and 3 allow correct classification in 65-70% of patients with severe post-traumatic coma. In addition, the normal pattern (grade 1) in our series has a positive predictive index of “awakening” of more than 90% and good functional recovery according to the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) of more than 80% [4].

In our series, a severe disability according to the GOS is associated, in nearly 100% of cases, with absent mono- or bilateral SEPs. Thus, a SEP performed already at 24-48 hours after severe head injury can predict two very divergent paths according to the length of stay in the ICU and subsequent rehabilitation processes in patients with normal SEP and absent or severely hypovolted SEP.

Finally, a comparative meta-analysis examined which was the best single early indicator of prognosis from among SEP, computed tomography (CT), EEG and GCS and photomotor reflex in post-traumatic and hypoxic-ischemic coma [22]. The work selected 26 comparable studies including over 800 patients and concluded that SEP is the best single prognostic indicator. Based on this evidence SEPs should always be associated with clinical tests for determining early prognosis of coma due to acute brain damage.

11.4 Continuous Neurophysiological Monitoring (EEG-SEP) in the ICU

As mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, continuous neurophysiological monitoring is required to establish clinical and therapeutic strategies in the comatose patient. Its purpose is to identify early the evolution of primary brain damage or the possible occurrence of secondary complications.

The demand for a greater use of such monitoring has several reasons:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree