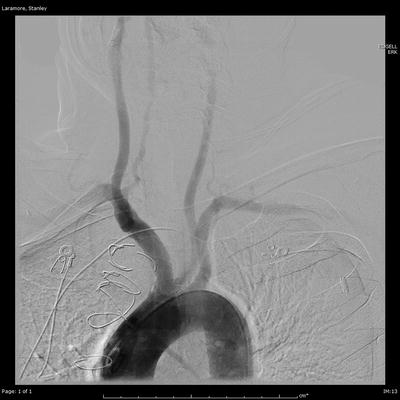

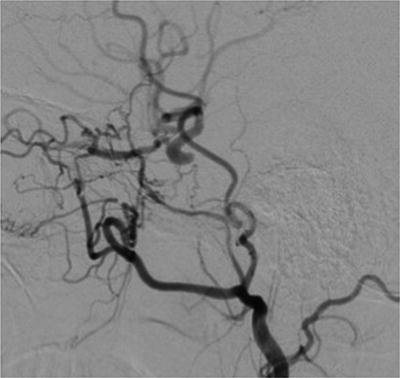

Fig. 2.1

Left anterior oblique projection of the standard aortic arch configuration

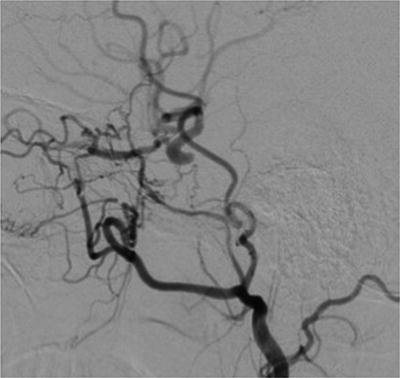

Fig. 2.2

Left anterior oblique projection of the bovine aortic arch variant

The External Carotid Artery

The external carotid artery (ECA) originates from the bifurcation of the common carotid artery at about the C4 vertebral level (Fig. 2.3a, b). It lies anteromedial to the internal carotid artery and then courses posterolaterally. Multiple angiographic projections may be required to view the ECA and its branches well.

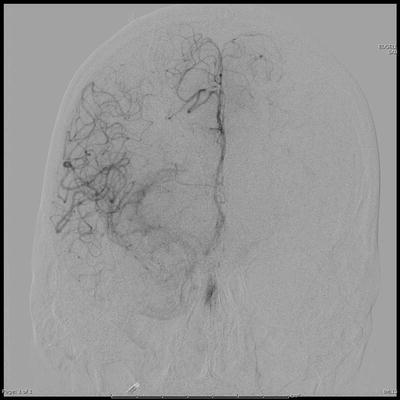

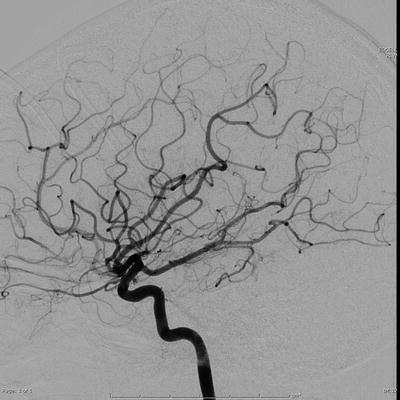

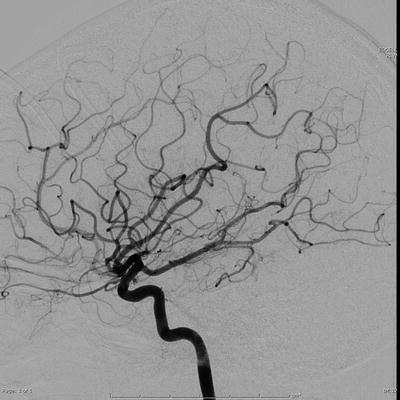

Fig. 2.3

External carotid artery in the anteroposterior (a) and lateral (b) projections

The ECA has eight branches (Fig. 2.4):

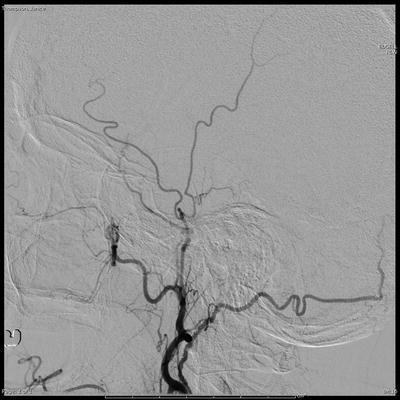

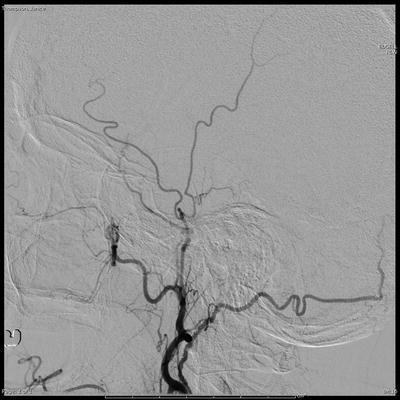

Fig. 2.4

Lateral projection images of the external carotid artery branches

1.

The superior thyroid artery—usually the first ECA branch, it supplies the larynx and superior aspect of the thyroid gland.

2.

Ascending pharyngeal artery [3]—it is the first posterior branch and supplies the pharynx and middle ear.

3.

Lingual artery—supplies the tongue and the oral cavity and anastomoses with other ECA branches.

4.

Facial artery—supplies the face and courses superolaterally to terminate near the medial canthus where it forms the angular artery. In about 26 % of cases, it may terminate in the lateral nasal (or alar) branch [4].

5.

Occipital artery—courses posterosuperiorly to supply the scalp and posterior aspect of the neck. It may anastomose with the vertebral artery or on occasion, may arise directly from it.

6.

Posterior auricular artery—small branch that supplies the scalp and the pinna.

7.

Superficial temporal artery—it is one of the terminal ECA branches and supplies the scalp.

8.

Internal maxillary artery—it is the larger of the two terminal branches of the ECA and supplies the nose. It can further be subdivided into three segments. The mandibular segment is where the largest branch of the IMA, the middle meningeal artery, originates. The pterygoid segment gives rise to the deep temporal arteries. The pterygopalatine segment is the terminal segment and supplies the nose through the sphenopalatine artery. It also gives rise to the infraorbital artery that supplies the lower eyelid and parts of the cheek and nose. The greater palatine artery also arises from this segment and supplies the soft palate and palatine tonsils [5].

External Carotid: Internal Carotid Anastomoses

1.

The ascending pharyngeal artery anastomoses with the ICA through the inferolateral trunk, the Vidian artery, and the caroticotympanic artery.

2.

Facial artery anastomoses with the ophthalmic artery through branches of the angular artery near the medial canthus (Fig. 2.5).

Fig. 2.5

Lateral projection images demonstrating the anastomotic connection between the angular branch of the facial artery and the ophthalmic artery

3.

The stylomastoid branch of the posterior auricular artery anastomoses with the caroticotympanic branch of the internal carotid artery.

4.

The internal maxillary artery (IMAX) is an important source of potential collateral flow between the ECA and ICA. It may anastomose with the petrous ICA through the Vidian artery, the cavernous ICA through the artery of the foramen rotundum, and the supraclinoid ICA through the ophthalmic artery. These are important channels that need to be kept in mind to prevent ischemic complications during head and neck embolization procedures. The middle meningeal artery may anastomose with branches from the cavernous segment of the ICA and can be an important source of collateral flow in carotid bulb atherosclerosis.

The Internal Carotid Artery

There are various classification systems of the segments of the ICA. One widely adopted system proposed by Bouthillier [8] is utilized in this chapter. This system divides the ICA into the following seven segments.

C1: Cervical ICA

The ICA usually originates from the CCA at C3–4 level. This segment has two distinct parts:

The carotid bulb—a dilated segment with a complex flow dynamic, this is a frequent site for the development of atherosclerotic disease.

The ascending cervical segment—from the bulb it courses upward within the carotid space.

There are no named branches that arise from the cervical segment. There can be considerable variation in the level of the carotid bifurcation. A medial origin of the ICA is common and may require an oblique projection to view the bifurcation clearly. Tortuosity and looping of the ICA are also visualized frequently and may present technical challenges to endovascular procedures.

Anomalies of the cervical ICA are uncommon with a congenital absence of the ICA being an extremely rare example. An absent or hypoplastic bony carotid canal on CT scan can present a clue to distinguish a developmentally hypoplastic ICA rather than an occlusion of a normally developed vessel [9]. Two important anastomotic channels that can originate from the cervical ICA are the persistent hypoglossal artery, which may connect it to the basilar artery, and the proatlantal intersegmental artery, which could anastomose with the vertebral artery.

C2: Petrous ICA

The petrous ICA has a vertical subsegment, a genu, and a horizontal subsegment. It may give off two small branches. The first of these is the Vidian artery (artery of the pterygoid canal) that more often arises from the ECA. As described in the previous section, it is an important anastomotic connection between the ICA and the IMAX, a branch of the ECA. The second is the caroticotympanic artery that supplies the middle ear cavity and may anastomose with the inferior tympanic artery, a branch of the APA.

Anomalies of the petrous ICA are rare but of clinical importance. An aberrant ICA may rarely be seen and can present as a retrotympanic pulsatile mass or can be found incidentally where significant bleeding from ear surgery may be encountered (see Chap. 16). The artery may also be mistaken for a middle ear tumor. A persistent otic artery is another anastomotic connection between the ICA and the basilar artery, which is extremely rare [10].

C3: Lacerum ICA

This segment begins at the end of the petrous carotid canal, courses above the foramen lacerum, and ends at the petrolingual ligament. Usually, it has no branches, although rarely the Vidian artery may originate from the C2–C3 segment junction.

C4: Cavernous ICA

The cavernous ICA begins at the petrolingual ligament and ends as it leaves the cavernous sinus through the dural ring. It is the most medial structure in the cavernous sinus, and the CN III, IV, and V1 and V2 run lateral to it, whereas CN VI runs inferolaterally. It is visualized well on a lateral view where it can be seen to have a posterior genu, a horizontal segment, and an anterior genu. This segment gives off three branches. The posterior trunk or the meningohypophyseal trunk (MHT) arises from the posterior genu and is often seen on angiography. Its branches include the inferior hypophyseal artery which supplies the pituitary gland, the marginal tentorial artery (MTA) which supplies the tentorium, and the clival branches to the clivus. The MTA, also known as the artery of Bernasconi–Cassinari, is sometimes involved in the pathologic supply of arteriovenous malformations or tumors, typically associated with tentorial meningiomas [11]. The lateral trunk or the inferolateral trunk (ILT) supplies the CN III, IV, and VI and dura of the cavernous sinus. It anastomoses with branches of the internal maxillary artery and the middle meningeal artery. In addition to these the cavernous ICA also gives off small capsular branches, which supply the pituitary gland. Anatomical variants of the cavernous ICA include increased tortuosity in this segment and paramedian ICAs. The latter, also known as “kissing” ICAs, occurs when the two ICAs course medially through the sella turcica. An important anomalous connection is a persistent trigeminal artery, which is the most common carotid–basilar anastomosis [12]. It arises from the posterior genu and is associated with increased prevalence of other vascular anomalies and aneurysms. The posterior genu is also often the site of direct carotid–cavernous fistulae formation [13].

C5: Clinoid ICA

This is the shortest ICA segment and lies between the proximal and distal dural ring, making it an interdural structure. It has no named branches but may give off small capsular arteries. Rarely, the ophthalmic artery may arise from this segment.

C6: Ophthalmic ICA

The first intradural segment of the ICA, the ophthalmic segment is surrounded by CSF. The first major intracranial ICA branch, the ophthalmic artery arises from this segment. It runs anteriorly through the optic canal and gives off three types of branches. The ocular branches provide arterial supply to the choroid and retina and include the central retinal artery and the ciliary arteries. Orbital branches of the ophthalmic artery supply the extraocular muscles and the orbit periosteum [14]. An important orbital branch is the lacrimal artery which may anastomose with the middle meningeal artery through the recurrent meningeal artery. An important but rare anatomic variant is a middle meningeal artery which may arise from the ophthalmic artery [15]. Extraorbital branches of the ophthalmic are also important sites of anastomoses with the ECA circulation through ethmoidal and facial arteries. The other important ICA branches from the C6 segments are the superior hypophyseal arteries which may be one or more in number. The C5 and 6 segments together make up the carotid siphon and are best visualized on lateral views on angiography [16].

C7: Communicating ICA

The C7 segment is the terminal ICA segment and begins proximal to the origin of the posterior communicating artery (PCom) and ends at the ICA bifurcation into the anterior and middle cerebral arteries. The first major branch from this segment is the PCom that arises from the posterior aspect of the ICA, runs above CN III, and gives off several small perforating branches. An important anatomical variant of the PCom is when it may supply the entire PCA territory in the absence of a P1 segment, also called a “fetal PCA” (Fig. 2.6). Another frequently encountered variant is a dilatation at the origin of the PCom called an infundibulum. It is important to distinguish these structures from true aneurysms. The second major branch of this segment is the anterior choroidal artery (AChA), which arises from the posteromedial aspect of the C7 segment. It has two segments, the cisternal and intraventricular. It has a variable but important territory of vascular supply including the optic tract, the posterior limb of the internal capsule, cerebral peduncle, medial temporal lobe, and choroid plexus. Rarely, a hypoplastic or hyperplastic AChA may be present. Another rare anomaly is when an AChA may arise proximal to the PCom.

Fig. 2.6

Lateral projection images of a fetal posterior cerebral artery anatomical variant

The Circle of Willis

The circle of Willis (COW) is a polygonal anastomotic ring that connects the anterior circulation with its contralateral counterpart as well as with the posterior circulation. It lies in the suprasellar cistern. Its contributing arteries are:

The internal carotid arteries, right and left

The anterior cerebral arteries (A1), right and left

The posterior communicating arteries, right and left

The posterior cerebral arteries (P1), right and left

The basilar artery

The anterior communicating artery

A complete COW is present in less than 50 % of all cases, and anatomic variants are extremely common [17]. The A1 segment may be hypoplastic (10 %) or absent (1–2 %). There may be duplicated or fenestrated anterior communicating arteries. A plexiform ACom is one where multiple channels may be present. A hypoplastic P1 segment may be seen with a fetal PCA. An anatomically isolated ICA occurs when there is an absent A1 and an ipsilateral fetal PCA. The entire COW is rarely visualized on a single angiogram, and different views and injections may be required to view it. There are important small perforating branches, which arise from the vessels in the COW. The ACA gives rise to the recurrent artery of Heubner, an artery that may inadvertently be clipped with an anterior communicating aneurysm due to its variable origin [18], and the medial lenticulostriate arteries. The anterior communicating artery itself gives rise to small perforating branches that supply the optic chiasm and parts of the corpus callosum. The posterior communicating arteries give rise to the anterior thalamoperforating arteries, which supply the thalamus and the optic tracts. The posterior thalamoperforators arise from the distal BA and the proximal PCAs, which supply the midbrain and the thalamus.

Anterior Cerebral Artery

The ACA is the smaller of the two terminal branches of the ICA. It is subdivided into three segments, the A1 or the precommunicating segment, the A2 or the postcommunicating segment, and the A3 or the distal ACA. The precommunicating segment is visualized well on a straight AP projection on angiography as it courses over the optic chiasm and below the anterior perforated substance and extends from the ACA origin to the junction of the ACA and the ACoA. The A2 segment extends from this point to the genu of the corpus callosum and is well visualized on the lateral projection. The proximal ACA segments give rise to perforating arteries, which supply parts of the anterobasal forebrain, corpus callosum, fornix, and septum pellucidum. The largest among these is the recurrent artery of Heubner, which has a variable origin [18]. It arises most often from the proximal A2 segment or the A1 segment. Less frequently it may arise from the ACoA. The ACA cortical branches are grouped according to their vascular territory. The first such group is the orbital branches, which includes the orbitofrontal artery. This group largely supplies the orbital surface of the frontal lobe. The second group is the frontal branches, which includes the frontopolar artery.

Distally, the ACA curves around the corpus callosum and bifurcates into two main branches, the pericallosal artery and the callosomarginal artery, and gives off the last group of cortical branches, the parietal branches. The distal ACA is also well visualized on a lateral projection. However on AP projection the pericallosal and callosomarginal arteries have a characteristic “smile and mustache” appearance in the late arterial phase [19] (Fig. 2.7).