age, infection, or atherosclerosis, which can weaken the vessel wall. Cerebral aneurysm is more common in women than in men; however, the opposite is true in children and adolescents, with a male to female ratio of 2:1. Additionally, cerebral aneurysm rupture is most prevalent in the 35- to 60-year-old age-group, with 50 being the mean age of occurrence.

Most common type

Secondary to congenital weakness of media

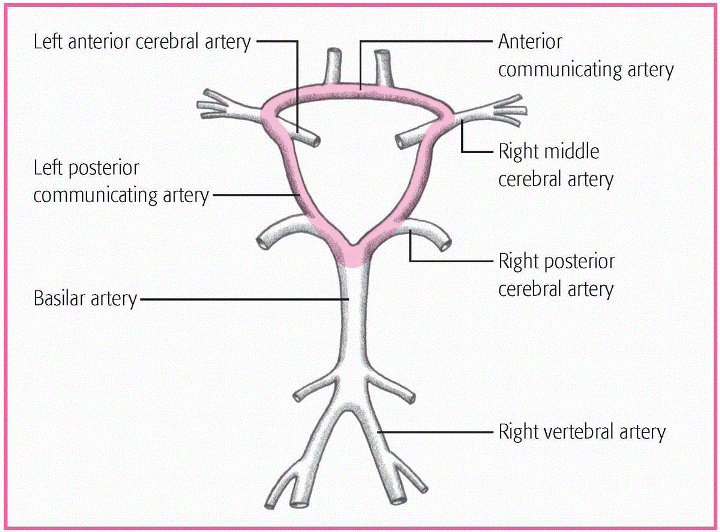

Usually occurs at major vessel bifurcations

Occurs at the circle of Willis

Has a neck or stem

Has a sac that may be partly filled with a blood clot

Similar to saccular aneurysm, but larger-3 cm or more in diameter

Behaves like a space-occupying lesion, producing cerebral tissue compression and cranial nerve damage

Associated with hypertension

Occurs with atherosclerotic disease

Characterized by irregular vessel dilation

Develops on internal carotid or basilar arteries

Rarely ruptures

Produces brain and cranial nerve compression or cerebrospinal fluid obstruction

Caused by arteriosclerosis, head injury, syphilis, or trauma during angiography

Develops when blood is forced between layers of arterial walls, stripping intima from the underlying muscle layer

Develops in the carotid system

Associated with fractures and intimal damage

May thrombose spontaneously

Microscopic

Associated with hypertension

Involves basal ganglia or brain stem

Rare

Associated with septic emboli that occur secondary to bacterial endocarditis

Develops when emboli lodge in arterial lumen, causing arteritis and weakening and dilation of arterial wall

into the brain tissue, where a large clot can cause potentially fatal increased intracranial pressure (ICP) and brain tissue damage.

Rupture

Subarachnoid hemorrhage

Brain tissue infarction

Cerebral vasospasm

Death

Rebleeding

Hydrocephalus

sudden onset of an unusually severe headache

nausea and vomiting

altered level of consciousness (LOC)

history of a period of activity, such as exercise, labor and delivery, or sexual intercourse, before the rupture.

pain above or behind an eye

possible photophobia

nuchal rigidity

back and leg pain

fever

restlessness and irritability

seizures

blurred vision

ptosis and vision disturbances (aneurysm adjacent to the oculomotor nerve)

hemiparesis, unilateral sensory deficits, dysphagia, vision deficits, and altered LOC (bleeding into the brain tissue).

COMPLICATION | SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS | ONSET | TREATMENT |

|---|---|---|---|

Rebleeding | Deterioration of neurologic status, decrease in level of consciousness (LOC), intensifying headache | 7 to 10 days after rupture | • Sedation, rest • Avoidance of Valsalva’s maneuver |

Cerebral vasospasm | Decrease in LOC, motor weakness or paralysis, vision deficits, changes in vital signs (particularly respiratory patterns) | Several hours to days after rupture | • Intravascular volume expanders • Induced hypertensive therapy • Calcium channel blockers |

Hydrocephalus | Mental changes, gait disturbances, general mental and physical deterioration | Can occur several hours to days later as a result | • Cerebrospinal fluid drainage via intraventricular catheter |

Grade I (minimal bleeding): The patient is alert, with no neurologic deficit; she may have a mild headache and nuchal rigidity.

Grade II (mild bleeding): The patient is alert, with a mild to severe headache, nuchal rigidity and, possibly, third-nerve palsy.

Grade III (moderate bleeding): The patient is confused or drowsy, with nuchal rigidity and, possibly, a mild focal deficit.

Grade IV (severe bleeding): The patient is stuporous, with nuchal rigidity, early decerebrate rigidity and, possibly, mild to severe hemiparesis.

Grade V (moribund [usually fatal]): If not fatal, the patient is in a deep coma or is decerebrate.

Angiography confirms the aneurysm’s location and displays the vessels’ condition.

Lumbar puncture may detect blood in the CSF, but this procedure is contraindicated if the patient shows signs of increased ICP.

Computed tomography scanning locates the clot and identifies hydrocephalus, areas of infarction, and the extent of blood spillage in the cisterns around the brain.

Magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance angiography show the extent of bleeding and the vessels’ condition.

|

bed rest in a quiet, darkened room (may last for 4 to 6 weeks)

avoidance of coffee, other stimulants, and aspirin

codeine or another analgesic, as needed

hydralazine (Apresoline) or another antihypertensive, if needed

a vasoconstrictor to maintain blood pressure at the optimum level (20 to 40 mm Hg above normal), if needed

corticosteroids to reduce meningeal irritation

phenytoin (Dilantin) or another anticonvulsant

phenobarbital (Luminal) or another sedative to relax the patient

nimodipine (Nimotop), a calcium channel blocker, to decrease cerebral vessel vasospasm

albumin for volume expansion, to decrease vasospasm

aminocaproic acid (Amicar), a fibrinolytic inhibitor, to minimize the risk of rebleeding by delaying blood clot lysis. (However, this drug’s effectiveness has been disputed.)

Maintain a patent airway and provide oxygen and ventilation, as needed.

Monitor the patient’s neurologic status.

Suction the patient cautiously (less than 20 seconds) to avoid increased ICP.

Monitor vital signs and pulse oximetry readings.

Provide frequent nose and mouth care.

Initiate aneurysm precautions: a quiet room, bed rest in the dark (with the head of the bed flat or elevated less than 30 degrees, as ordered), limited visitors, avoidance of such stimulants as coffee, avoidance of Valsalva’s maneuver and other strenuous activity, and restricted fluid intake.

Monitor for signs of rebleeding, intracranial clot, vasospasm, or other complications.

Administer medications, as ordered, and monitor effects.

Provide emotional support to the patient and his family. Encourage them to talk about their concerns. Listen carefully and answer their questions honestly and completely.

Reposition the patient every 2 hours and assess skin condition. Provide skin care.

Assist with active range-of-motion (ROM) exercises; if the patient is paralyzed, perform passive ROM exercises.

Administer I.V. fluids and monitor intake and output. Maintain fluid volume to decrease the risk of vasospasm.

Assess swallowing ability and assist with meals, as appropriate; administer enteral feedings, if ordered.

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH A CEREBRAL ANEURYSM

TEACHING THE PATIENT WITH A CEREBRAL ANEURYSM

the disorder and its implications

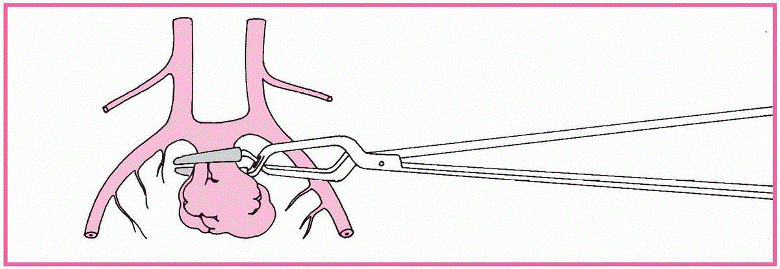

treatment options, such as surgery and therapy

medication administration, dosage, and possible adverse effects, and when to notify the physician

the importance of good nutrition and what types of food may be best based on swallowing ability

range-of-motion exercises to improve muscle tone and strength

types of therapy that would be beneficial, such as physical therapy, speech therapy, and occupational therapy

signs and symptoms of complications

the importance of follow-up care

the benefit of utilizing available community support groups such as the local chapter of the Brain Aneurysm Foundation.

Initiate seizure precautions, if indicated.

Monitor head dressings and provide wound care.

Monitor ICP and cerebral perfusion pressures, and provide measures to maintain adequate readings.

Monitor for postoperative complications, including sudden hemiplegia, psychological changes (disorientation, amnesia, Korsakoff’s syndrome, personality impairment), fluid and electrolyte disturbances, and GI bleeding.

Provide appropriate education to the patient and his family before discharge. (See Teaching the patient with a cerebral aneurysm.)

oxygen supply and commonly causes serious damage or necrosis in brain tissues. The sooner circulation returns to normal after stroke, the better chances are for complete recovery. About half of those who survive stroke suffer a disability and experience a recurrence within weeks, months, or years.

atrial fibrillation

TIA

atherosclerosis

hypertension

renal disease

carotid stenosis

diabetes mellitus

cardiac or myocardial enlargement

sickle cell anemia

hypercoagulable states

hyperlipidemia

TYPE OF STROKE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

ISCHEMIC | |

Thrombotic | • Most common type of stroke • Commonly the result of atherosclerosis; also associated with hypertension, smoking, or diabetes (disease process similar to myocardial infarction [MI]) • Thrombus in extracranial or intracranial vessel blocks blood flow to the cerebral cortex • Carotid artery most commonly affected extracranial vessel • Common intracranial sites include bifurcation of carotid arteries, distal intracranial portion of vertebral arteries, and proximal basilar arteries • May occur during sleep or shortly after awakening, during surgery, or after an MI |

Embolic | • Second most common type of stroke • Embolus from heart or extracranial arteries floats into cerebral bloodstream and lodges in middle cerebral artery or branches • Embolus commonly originates during atrial fibrillation • Typically occurs during activity • Develops rapidly |

Lacunar | • Subtype of thrombotic stroke • Hypertension creates cavities deep in white matter of the brain, affecting the internal capsule, basal ganglia, thalamus, and pons • Lipid coating lining of the small penetrating arteries thickens and weakens wall, causing microaneurysms and dissections |

HEMORRHAGIC | |

• Third most common type of stroke • Typically caused by hypertension or aneurysm rupture • Blood supply to area from the ruptured artery diminished and surrounding tissue compressed by accumulated blood |

individual history of stroke

family history of stroke

advanced age

smoking

use of hormonal contraceptives

lack of exercise.

vessel; edema may produce more clinical effects than thrombosis itself, but these effects subside along with the edema. (See How stroke affects the body.)

An ischemic stroke, which can be thrombotic or embolic, causes ischemia. Some of the neurons served by the occluded vessel die from lack of oxygen and nutrients.

Neuron death results in cerebral infarction, in which tissue injury triggers an inflammatory response that increases intracranial pressure (ICP).

Injury to surrounding cells disrupts metabolism and leads to changes in ionic transport, localized acidosis, and free radical formation.

Calcium, sodium, and water accumulate in the injured cells, and excitatory neurotransmitters are released.

Consequent continued cellular injury and swelling set up a cycle of further damage.

Impaired cerebral perfusion causes infarction, and the blood itself acts as a space-occupying mass, exerting pressure on brain tissues.

The brain’s regulatory mechanisms attempt to maintain equilibrium by increasing blood pressure to maintain cerebral perfusion pressure.

The increased ICP forces cerebrospinal fluid out, thus restoring the balance. If the hemorrhage is small, the patient may live with only minimal neurologic deficits. If the bleeding is heavy, ICP increases rapidly and perfusion stops. Even if the pressure returns to normal, many brain cells die.

Initially, the ruptured cerebral blood vessels may constrict to limit the blood loss.

This vasospasm further compromises blood flow, leading to more ischemia and cellular damage.

If a clot forms in the vessel, decreased blood flow promotes ischemia.

If the blood enters the subarachnoid space, meningeal irritation occurs.

Blood cells that pass through the vessel wall into the surrounding tissue may break down and block the arachnoid villi, causing hydrocephalus.

Cerebral ischemia and infarction can ultimately affect the autonomic nervous system, which can alter blood vessel constriction and dilation, heart rate, blood pressure, and cardiac contractility.

Cardiovascular effects are increasingly problematic if the patient has an underlying disorder, such as heart disease or hypertension.

Cerebral infarction can lead to a disturbance in impulse transmission via the cranial and peripheral nerves, altering motor and sensory function.

Changes in sensation or mobility can lead to pressure areas, especially with prolonged bed rest or limited activity. In addition, the ability of the blood vessels to constrict and dilate as necessary may be altered, increasing the risk of impaired blood flow to the area. Subsequently, pressure ulcers may develop.

If infarction resulting from increased ICP and decreased perfusion involves the respiratory center in the medulla, respiration—including the depth and rate—can be affected because nerve impulse transmission via the phrenic nerves to the diaphragm and intercostal nerves to the intercostal muscles is interrupted.

If the pons (the location for apneustic and pneumotaxic centers) is affected, breathing patterns become altered and impulse transmission via the cranial nerves (CN) may be interrupted.

If the glossopharyngeal (CN IX) and vagus nerves (CN X) are affected, swallowing may be impaired and aspiration may occur.

cerebral artery, causing necrosis and edema. If the embolus is septic and infection extends beyond the vessel wall, encephalitis or an abscess may develop.

Sensory impairment

Motor impairment

Altered level of consciousness (LOC)

Aspiration

Contractures

Complications of immobility

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

Pulmonary emboli

Depression

Malnutrition

history of one or more risk factors for stroke

sudden loss of voluntary muscle control or onset of hemiparesis or hemiplegia

sudden onset of speech disturbance or communication problem

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree