Nocturnal Events

Troy Payne

In the course of clinical practice, many unusual nocturnal phenomena may be described by patients. The correct diagnosis can often be ascertained by distinguishing certain clinical features from the history. In other cases, the etiology of the events may be determined only by polysomnography. With modern digital equipment, additional leads can easily be applied to assist in diagnosis. Additional electroencephalography (EEG) leads should be used if a seizure disorder is suspected. Additional electromyography (EMG) leads can be useful in patients with movement disorders. Digital video acquired with a pan-tilt camera can capture the event of concern. What follows is a collection of clinical vignettes, often with a sample page from a polysomnogram. This is followed by a discussion of the differential diagnosis.

PERIODIC LIMB MOVEMENT DISORDER

Chief complaint: “She jerks at night in her sleep” per husband.

History of present illness: A 35-year-old woman presents with her husband. She complains that for the last 2 years she has felt tired during the day. Her family physician thought she might be depressed and put her on an antidepressant. This did not really help her sleepiness. She states she has never snored. She goes to bed regularly at 10:30 PM and falls asleep quickly. She awakens from sleep a few times in the first 2 to 3 hours. She then sleeps through the rest of the night and awakens the next morning at 6:30 AM before her alarm clock sounds at 6:45 AM. She is usually tired all day. Her husband adds that she often jerks her legs in her sleep especially in the first half of the night. She denies having any restless legs symptoms at night or during the day.

Medical history: History of anemia felt to be secondary to fibroids; hemoglobin stabilized in normal range after hysterectomy 4 years ago. Depression.

Medications: A serotonin uptake inhibitor, which she has tried for 6 months.

Family history: Her mother has insomnia and takes clonazepam at night. Her brother had febrile seizures as a child and has very rare complex partial seizures under good control with an anticonvulsant medication as an adult.

Review of systems: No headaches, vertigo, dizziness, episodes of loss of consciousness, palpitations, difficulty breathing, snoring, nausea, back pain, leg pain, incontinence, or weight change. She complains of some intermittent insomnia and daytime tiredness.

Examination: Well appearing woman who yawns a couple of times and does appear tired. Sixty-eight inches tall; 155 pounds. Blood pressure 118/69 mm Hg and pulse 72. Normal nasal anatomy and oropharynx by examination. Regular heart rate and rhythm. Lungs are clear to auscultation. Completely normal neurologic examination with no evidence of neuropathy. Epworth Sleepiness Scale score high at 14. Laboratory studies show a normal hemoglobin, ferritin, iron level, and total iron binding capacity.

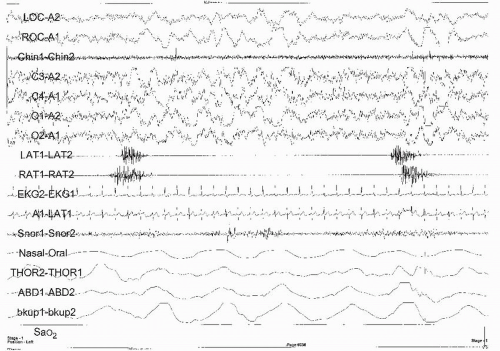

Polysomnogram and Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT): Respiratory disturbance index (RDI) 0.1. Minimum oxygenation 94%. There is an increase in stage 1 sleep at 32% and a decrease in the expected percentage of stage N3 sleep. Periodic leg movement (PLM) index 42; PLM arousal index 15.2. Mean sleep latency 4.9 minutes with no rapid eye movement (REM) sleep on MSLT (Fig. 10-1).

Diagnosis and differential: Periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) is “characterized by periodic episodes of repetitive, highly stereotyped, limb movements that occur during sleep” (1, p. 182). While these movements usually occur in the legs, they can also occur in the arms. There is usually extension of the toe and flexion of the ankle, knee, and hip. Most patients are not aware of the movements. The sleep disruption associated with the

movements can lead to insomnia or daytime somnolence. Periodic limb movements usually start soon after onset of nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. They are usually less common in stage 3 sleep and rarer in stage R sleep. There is a repetitive increase in EMG activity (most often measured over the anterior tibialis muscle) of at least 8 µV lasting 0.5 to 10 seconds (2, p. 41). The movement can be synchronous or asynchronous with the other leg or only involve one extremity. Both legs (and even the arms) should be monitored if PLMD is suspected. The movements are between 5 and 90 seconds apart. Most of the time, the movements occur every 20 to 40 seconds. Four or more consecutive movements are needed to count them as PLMs. The PLM index is the total number of movements divided by the total hours of sleep. A PLM index is considered abnormal in children if over 5 and in adults if over 15 (2, p. 85). However, one can have an elevated PLM index with no clinical sequelae. Often, PLMs are associated with arousals. A PLM arousal index may also be noted on the sleep study interpretation. Although many assume that the higher the PLM arousal index the more likely one is to suffer from daytime sleepiness, this has not been proven (3). To have PLMD, the PLMs must cause disturbance in one’s sleep or cause excessive daytime fatigue (Table 10-1).

movements can lead to insomnia or daytime somnolence. Periodic limb movements usually start soon after onset of nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. They are usually less common in stage 3 sleep and rarer in stage R sleep. There is a repetitive increase in EMG activity (most often measured over the anterior tibialis muscle) of at least 8 µV lasting 0.5 to 10 seconds (2, p. 41). The movement can be synchronous or asynchronous with the other leg or only involve one extremity. Both legs (and even the arms) should be monitored if PLMD is suspected. The movements are between 5 and 90 seconds apart. Most of the time, the movements occur every 20 to 40 seconds. Four or more consecutive movements are needed to count them as PLMs. The PLM index is the total number of movements divided by the total hours of sleep. A PLM index is considered abnormal in children if over 5 and in adults if over 15 (2, p. 85). However, one can have an elevated PLM index with no clinical sequelae. Often, PLMs are associated with arousals. A PLM arousal index may also be noted on the sleep study interpretation. Although many assume that the higher the PLM arousal index the more likely one is to suffer from daytime sleepiness, this has not been proven (3). To have PLMD, the PLMs must cause disturbance in one’s sleep or cause excessive daytime fatigue (Table 10-1).

Individuals with restless leg syndrome (RLS), narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea and a variety of painful conditions often have PLMs on a polysomnogram. RLS is sometimes associated with anemia, iron deficiency, uremia, and pregnancy. Although all patients with PLMD and most patients with RLS have PLMs on a sleep study, only the patients with RLS have the daytime annoying sensations in their limbs that improve with movement. Use of caffeine, neuroleptics, alcohol, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, or tricyclic antidepressants can cause or worsen PLMs. Withdrawal of benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and certain hypnotics can cause or aggravate PLMs. These movements are rare in children but increase in prevalence with age. PLMs may be seen in patients who

are asymptomatic. Inadequate sleep habits, psychophysiologic insomnia, and other causes of daytime tiredness need to be considered and treated before placing a patient on medication for this condition.

are asymptomatic. Inadequate sleep habits, psychophysiologic insomnia, and other causes of daytime tiredness need to be considered and treated before placing a patient on medication for this condition.

TABLE 10-1 DIFFERENTIAL FOR TWITCHING OR JERKING OF EXTREMITIES IN SLEEP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

There are a few conditions that mimic PLMs. Sleep starts or hypnic jerks are frequently mentioned by patients. These occur in drowsiness, may be associated with a feeling of falling, and do not recur repetitively throughout sleep. Seizures can cause nighttime kicking movements, but may also cause nocturnal enuresis, morning musculoskeletal soreness, or bleeding from oral maceration. An expanded additional 16-lead EEG on the polysomnogram is invaluable in identifying these individuals. Many people with sleep apnea have periodic limb movements that disappear with initiation of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). If a patient has a high PLM index even after titrated to an appropriate CPAP and continues to complain of sleepiness despite faithful use of CPAP, consider treating the PLMs.

This woman was treated with pramipexole after a trial of the antidepressant did not help her PLMD. She found her sleep much more refreshing. Her husband stated that she hardly ever kicked in bed at night anymore. Similar to medical treatment of RLS, dopamine agonists, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, and analgesics are often helpful in the treatment of PLMD.

RHYTHMIC MOVEMENT DISORDER

Chief complaint: Nocturnal movements.

History of present illness: A 40-year-old patient with a static encephalopathy presents with the director of the group home into which he just moved. The patient suffered perinatal hypoxia and had developmental delays as a child. He has never had a documented seizure. His father died several years ago in a motor vehicle accident. The patient’s mother recently passed away and the patient moved into the group home last month. The director states that the patient usually goes to bed around 10 PM and gets up at 6:30 AM. The group home director states that a supervisor has found the patient rhythmically kicking in bed or knocking the back of his head against the bed. This almost always happens early in the night, soon after bedtime. The patient usually alerts easily from these events but has no knowledge of them. The patient has never bitten his tongue or had incontinence during these events.

Medical history: Static encephalopathy from perinatal hypoxia. Full Scale IQ 61.

Medications: None.

Social history: Lived his whole life with his parents. He recently moved to group home after his mother’s death.

Family history: Father had sleep apnea and was treated with CPAP.

Review of systems: Denies restless leg symptoms, headaches, incontinence, abdominal pain, musculoskeletal pain, or nightmares.

Physical examination: Seventy inches tall; 225 pounds. His oropharynx appears normal. No maceration of tongue or buccal mucosa. No abrasions or bruising on scalp. Moderately mentally retarded. Appears to have normal tone and reflexes. No evidence of neuropathy. Has diffuse mild hypotonicity and a slightly wide-based gait.

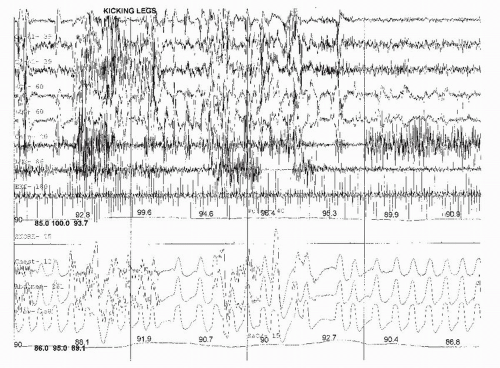

Polysomnogram: Diffuse baseline slowing of EEG at 7 Hz. No epileptiform activity. Delayed sleep onset at 63 minutes. Rhythmic movement bursts for much of the first hour of the study. RDI 0.2. Minimum oxygenation 90%. Video showed the patient bouncing his legs or having rocking behaviors that caused movement artifact on the polysomnogram (Fig. 10-2; Table 10-2).

Diagnosis and differential: Sleep-related rhythmic movement disorder (RMD) is “characterized by repetitive, stereotyped, and rhythmic motor behaviors (not tremors) that occur predominantly during drowsiness or sleep and involve large muscle groups” (1, p. 193). This can manifest as repetitive head banging, leg banging, or body rolling. The movements typically start during drowsiness. Movements typically occur at a frequency of 0.5 to 2 times per second and cluster in groups of at least four (2, p. 43). Although very common in normal infants, it is sometimes associated with a static encephalopathy, autism, or psychopathology in older children and adults. It is certainly seen in individuals of normal intelligence. It is thought to have a self-soothing effect for some individuals. It appears to be more common in males. The noise from the movements can be disturbing to family members. My practice includes one teenager who developed a subdural hematoma from RMD. It is very important to have the technologist accurately document what was seen at the time this occurs in the sleep laboratory. Continuous video monitoring usually easily confirms the diagnosis.

The differential includes nocturnal seizures, masturbation, bruxism, and PLMD. Nocturnal seizures can usually be diagnosed by concomitant extra 16-channel EEG and review of the video. Masturbation has been mistaken for RMD. Bruxism and PLMD are usually easily distinguished on the sleep study. Gasping respirations from sleep apnea can cause rhythmic movements.

This patient could have had these movements since early childhood, or they could have just started from the stress of the recent move to the group home. A counselor spent several sessions with the patient and the group home personnel to help with the transition to the new living environment. The movements improved dramatically, but worsened during times of greater stress.

BRUXISM

Chief complaint: Morning headaches and facial pain.

History of present illness: A 26-year-old woman presents with headaches. Patient states she has been treated by a neurologist for chronic daily headaches for the past year

with only limited success. She states she often awakens with pain in her temples. Over time, a beta blocker, a calcium-channel blocker, and one anticonvulsant medication were tried, but the headaches never completely went away. When the headaches are at their worst she has trouble concentrating. She has never had scintillating scotomata, photophobia, or vomiting. She can work through the headaches. She complains of chronic fatigue and thinks she snores rarely.

with only limited success. She states she often awakens with pain in her temples. Over time, a beta blocker, a calcium-channel blocker, and one anticonvulsant medication were tried, but the headaches never completely went away. When the headaches are at their worst she has trouble concentrating. She has never had scintillating scotomata, photophobia, or vomiting. She can work through the headaches. She complains of chronic fatigue and thinks she snores rarely.

FIGURE 10-2 Rhythmic kicking movements seen during relaxed wakefulness and stage 1 sleep; 120-second page. |

Medical history: Anxiety disorder. Chronic daily headaches.

Medications: Paroxetine (Paxil).

TABLE 10-2 DIFFERENTIAL FOR RHYTHMIC MOVEMENTS DURING SLEEP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Social history: Attorney. Single and lives alone. She is an intern in a prestigious law firm. She smokes half a pack of cigarettes per day. She rarely drinks alcohol.

Family history: No one in her family has headaches or migraines. Sister has depression.

Review of systems: Daily headaches often worse in the morning or when in stressful situations. No recent weight change. No coughing or abdominal pain. Recently visited her family doctor and had a normal complete blood cell count and comprehensive chemistry panel.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree