This paradigm shift has left both practitioners and patients in a quandary about how to manage weight and health. A traditional view argues that excess weight is associated with an increased risk of morbidity and mortality; therefore, weight loss through diet and exercise is a principal method for obese patients to improve their health (22). A non-dieting view questions the relationship between excess weight and mortality; moreover, it contends that dieting is both ineffective and harmful (1, 4, 5, 23–25). If improved health is the desired endpoint, should healthcare professionals encourage overweight patients to diet or not to diet? In an attempt to shed light on this question, this chapter updates a review by Foster and McGuckin (26) regarding the assumptions of the non-dieting movement, the goals and methods of non-dieting programs, and the research evaluating their efficacy.

Assumptions

The growing discontent with dieting and the search for alternative approaches are based on three premises: 1) dieting is ineffective; 2) dieting is harmful; and 3) long-standing beliefs about the causes and consequences of overweight are incorrect. Non-dieting programs have been developed to address these concerns and offer alternatives to those who have been disappointed, or even harmed, by traditional dieting attempts.

Dieting Is Ineffective

A principal driving force of the non-dieting movement is the well-established finding that diets fail to produce their most desired outcome—long-term weight loss (3–5, 27, 28, see also Chapter 17 for an overview of the efficacy of dietary interventions). Any weight that is lost during dieting is soon regained. It is argued that, in the long term, dieters usually end up weighing more, not less, after a diet. Miller (25) states that “review articles on the effectiveness of diet and exercise for weight control over the past 40 years have concluded that diet and exercise are ineffective in producing substantial long-term weight loss for a majority of the participants” (p. 212). A recent review cited data from 14 weight-loss studies and found that, while the average weight loss was 14 kg, by follow-up (at least four years in duration), most of the weight had been regained (average weight regain 11 kg) (4). These consistent, lackluster results have fueled the development of non-dieting alternatives.

Dieting Is Harmful

A second tenet of the non-dieting movement is that dieting confers significant untoward consequences across several domains (e.g., psychological, cognitive, health). The drive for thinness and the demonization of “fat” and “overweight” are seen as byproducts of the fashion, cosmetic, and media industries (6). Psychological consequences of dieting reportedly include depression, anxiety, anger, irritability, food and weight preoccupation, social isolation, and diminished body image and self-esteem (3, 5, 16, 20, 29). Cognitive impairments associated with dieting include diminished reaction time and increased distractibility (5), and impaired control of speech (30). In addition, dieting is thought to lead to increases in disordered eating, particularly binge-eating (5, 24, 29, 31).

Dieting is also believed to confer significant negative physical consequences, such as reduced metabolic rate, hypotension, dizziness, hair loss, and decreased bone mass (1, 3, 16). Berg (1) noted the untoward consequences associated with various weight-loss medications, such as increases in blood pressure and heart rate, as well as cardiac valvulopathy. In addition, she described the side-effects associated with very-low-calorie diets, such as gallstone formation, anemia, constipation, headaches, dry skin, muscle cramps, bad breath, and even death. Some data have shown that weight fluctuation is associated with increased mortality (23). With findings such as these, Gaesser (32) has suggested that weight loss “may do more harm than good, particularly for persons with no pre-existing health conditions” (p. 1122).

“Weight cycling”—repeated cycles of weight loss and regain—is believed to magnify the ill effects of dieting and may even lead to the very conditions (e.g., cardiovascular disease, certain cancers) that dieting seeks to improve (4, 29, 32–34). Ernsberger and Koletsky (24) concluded that “during regain of lost weight, all of the short-term benefits of weight loss are undone, and in many cases risk factors become worse during weight regain than they were at the starting level” (p. 233). Many contend that dieting, rather than producing sustained weight loss, actually prevents weight loss (35) and promotes subsequent weight gain (16). In other words, dieting can “make you fat” (13).

In summary, Polivy and Herman (36) concluded that dieting can “create more problems than it solves” and creates “seen and unseen eating problems which beset our population” (6, p. 68). These negative consequences of dieting are even more disturbing given that dieters will not experience any sustained weight loss (as described above). Thus, many suggest that there is an overemphasis on weight loss in our society (37), and dieting is viewed as a treatment that is both harmful and ineffective (4, 38).

Long-Standing Beliefs Are Incorrect

A third guiding principle of the non-dieting movement is that fundamental assumptions about the causes and consequences of overweight are incorrect (3, 20, 25). Non-dieting proponents view developments in the understanding of the genetics of body weight as evidence for a biological rather than a behavioral etiology of obesity. They argue that, if excess weight were simply a matter of inappropriate eating habits, behavioral treatments that seek to modify those habits would work. The fact that they do not suggests a less behaviorally based etiology.

The non-dieting movement also challenges the assumption that being overweight is unhealthy. Kano (14) argued that “it is extremely misleading, if not plain wrong, to say that being fat is unhealthy” (p. 15). Many suggest that the association of overweight with certain medical conditions can be explained by a third factor, such as repeated dieting, inactivity, or smoking to suppress appetite (4, 24, 25). Based on the findings by Blair and colleagues (37, 39, 40) suggesting that “fitness rather than fatness” modifies risk, non-dieting advocates suggest that increased fitness rather than decreased weight should be the principal means to improve health (32). Proponents further argue that moderate degrees of excess weight may actually diminish the risk of many conditions, such as osteoporosis and certain types of cancer (14, 24, 32).

Independent of whether excess weight increases risk, many point to the lack of long-term data showing that weight loss improves health (25, 32, 41). A New England Journal of Medicine editorial summarized the data linking weight loss to improved medical benefits as “limited, fragmentary, and often ambiguous” (8). Campos and colleagues (2) have argued that “the central premise of the current war on fat—that turning obese and overweight people into so-called ‘normal weight’ individuals will improve their health—remains an untested hypothesis” (p. 57). If obesity is not harmful and weight loss is not beneficial, dieting is not only ineffective and harmful, but unnecessary as well.

Non-Dieting Programs: Goals and Methods

Goals

Although non-dieting programs differ greatly in the methods they employ, they all generally seek to 1) increase awareness of dieting’s ill effects; 2) educate patients about the biological basis of body weight; 3) use internal cues such as hunger and fullness, rather than external cues such as calories and fat grams, to guide eating behavior; 4) improve self-esteem and body image through self-acceptance rather than through weight loss; and 5) increase physical activity.

There is less consensus across programs about the goals for weight loss. Several programs recommend the attainment of an “optimal” or “natural” weight, defined loosely as the weight one’s body is meant to maintain without dieting or restriction-induced overeating (13, 14, 16). Some attempt to induce a slower weight loss than traditional approaches (42) or promote a “Health-At-Every-Size” approach (43), while others seek to prevent weight gain (44). In general, most programs actively discourage weight loss for its own sake but acknowledge that a change in weight (either loss or gain) may occur when eating habits are normalized.

Methods

Although these general goals are consistent across non-dieting programs, the methods to achieve these outcomes vary considerably. This section reviews the various strategies advocated in non-dieting programs relative to the goals described above.

Increasing Awareness of the Ill-Effects of Dieting

Most programs begin with participants completing detailed dieting histories to underscore the central tenets that dieting is ineffective and harmful. Polivy (45), for example, has participants complete detailed histories of all previous diets, including the amounts lost and regained, as well as the financial cost associated with each failed attempt. In group settings, members’ experiences are summed to illustrate that thousands of dollars have been spent, only for the members to end up weighing more than they did before their first diet. Participants also complete symptom checklists concerning previous dieting attempts to underscore the deleterious physical and psychological consequences described above. Such histories are meant to personalize the concept that dieting has adverse consequences (e.g., lost money, food deprivation, physical symptoms) and does not produce long-term weight loss. In addition, non-dieting interventions educate participants about the misguided motivations for dieting and/or weight loss, including social acceptance and unmet emotional needs (15, 45, 46).

Education About the Biological Basis of Body Weight

Typically, participants are provided with written materials about the strong genetic influences on body weight. They are encouraged to use their own weight and dieting histories to find a “natural weight”—a stable weight that occurs when they are neither dieting nor overeating as a result of dieting (45). Participants are also educated about the biological responses to energy restriction, such as decreases in resting metabolic rate and thyroid hormones. This information is used to emphasize that weight cannot be easily changed and to debunk the notion that everyone can or should meet the same standard.

Guiding Eating Behavior

Instructions regarding dietary intake fall into two domains. The first concerns the process of eating (i.e., how to eat), while the second concerns the product (i.e., what to eat). Regarding the process of eating, a central recommendation in most programs is to “stop dieting” (11, 12, 16, 17, 47, 48). Participants are encouraged to abandon dieting behaviors, such as going for long periods without eating, avoiding forbidden foods, and getting weighed frequently. The purpose of doing so is to shift from a dieting mentality in which food is the enemy, to a state of mind in which food is enjoyed (14, 46). This shift is thought to normalize food consumption patterns, reduce disordered eating, and assist people in overcoming their preoccupation with food (29, 44, 49, 50).

Another aspect of changing the process of food consumption is to base eating on internal cues (e.g., hunger, satiety) rather than external cues (e.g., calories, fat grams). Participants are encouraged to rate their hunger and fullness before, during, and after eating to become more aware of their internal signals (13, 16, 49, 51). In addition, participants are instructed to eat regular, balanced meals to establish a predictable pattern of hunger and satiety (50, 52).

Recommendations regarding what specifically should be eaten vary considerably. At one end of the continuum, everything is “allowed” in terms of both type and quantity, particularly previously “forbidden” foods (13, 53). Other programs provide strategies for “ways we can feel good in the bodies we have” (54) or purport to have “10 amazing secrets” to lose weight without dieting (e.g., Develop Your Ability to Focus, Fear of Food Keeps You Fat, Redefine the “Perfect Body”) (55). Another program, “Am I Hungry” (56) (see Figure 16-2) describes their philosophy as a “non-diet approach to weight management” through which a person will learn “intuitive eating” and will be empowered to use the “natural ability to eat just the right amount of food.” Such strategies often lack sufficient specificity for implementation.

Figure 16-2 Website Screenshot from “Am I Hungry”

Source: May, M. Am I Hungry? (2010, December 13). www.amihungry.com/am-i-hungry-philosophy.shtml.

Others recommend eating whatever internal signals dictate (e.g., “Eat when you’re hungry and stop when you’re full” or “Eat what you like”). Carrier and colleagues (29) encourage “demand feeding,” characterized by eating what one craves when one is hungry. Finally, others give specific nutritional prescriptions, including energy levels (1,800 kcal/day) (42), reductions in fat and refined sugar (47, 57, 58), or directions to follow consensus-based nutrition guidelines, such as government issued guidelines or consensus statements from professional organizations. Thus, the recommendations for dietary intake range from unrestricted consumption to guidelines quite similar to those found in traditional dieting programs.

Improving Psychological Well-Being

The improvement of psychological health is a major target of virtually all non-dieting programs. Although overall well-being is the goal, considerable attention is given to ameliorating weight-based self-esteem and body image disparagement (14, 29, 46, 52, 59). The aim is to promote enhanced self-esteem and a positive body image without linking these improvements to weight loss (60). This goal is often rooted in feminist theory, which questions the body ideals set for women in our society (61).

A principal technique for improving self-esteem and body image is to have participants engage in behaviors that they have “put on hold” until they lose weight (14, 45, 62, 63). These may include taking a cruise, buying new clothes, asking for a raise, going to a high school reunion, terminating an unsatisfactory relationship, or wearing certain types or colors of clothing. Participants are also encouraged to identify and counter their own anti-fat attitudes. Cash’s (64) book is a very useful self-help guide to improving body image, and Johnson’s (65) book is an excellent resource for minimizing the link between weight and self-worth.

Increasing Physical Activity

Non-dieting programs vary in their approach to physical activity. Some do not address exercise at all (46) or briefly mention the importance of regular exercise without providing specific definitions (66). The most common recommendation is to increase activity in ways that are enjoyable (14, 52, 67, 68). Physical activity is encouraged as a means to feel good—”to nourish the body, not reduce it” (67). Therefore, activity is not viewed as a means to the end of weight loss, but rather as a pleasurable activity in its own right. Finally, other programs provide specific exercise regimens (42, 47, 53, 58). Some offer specially made fitness videos or classes (50), while others give specific goals for duration, frequency, and intensity (16, 69, 70).

Suggestions for physical activity include having participants move their bodies in ways they enjoy. This often involves encouraging patients to engage in activities often considered inappropriate for overweight persons (e.g., dancing, jumping rope, swimming, sex). Lyons and Burgard’s (69) Great Shape and Dunn and colleagues’ Active Living Every Day (71) provide useful suggestions for making small and enjoyable changes in physical activity.

Empirical Support

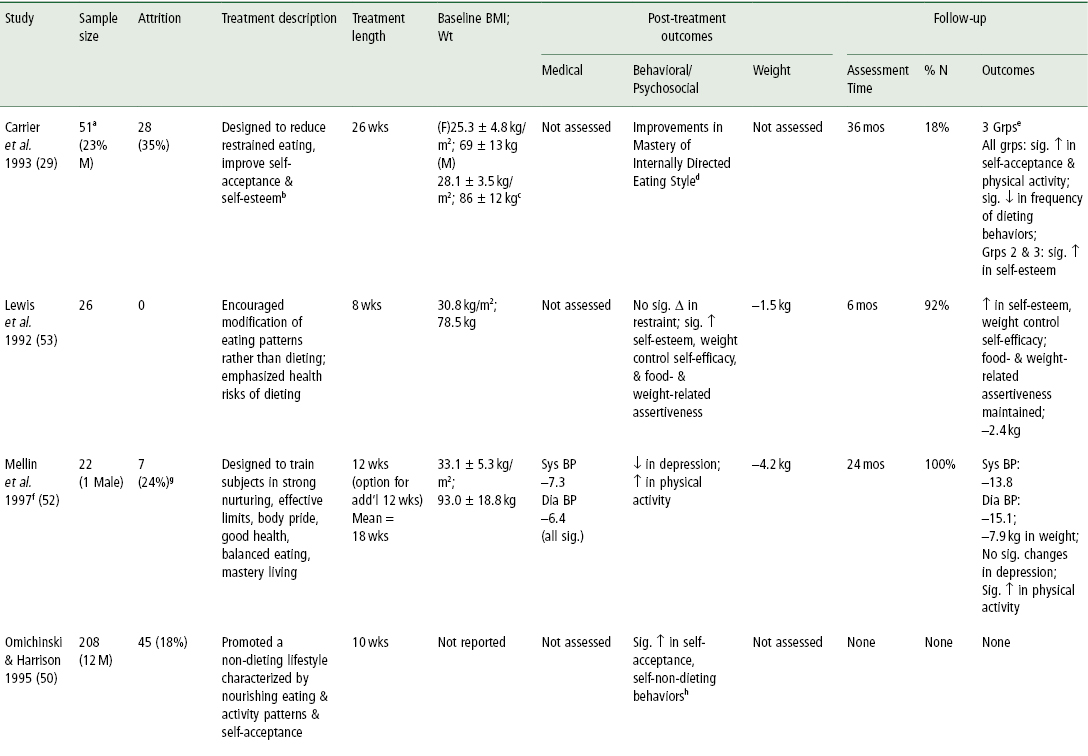

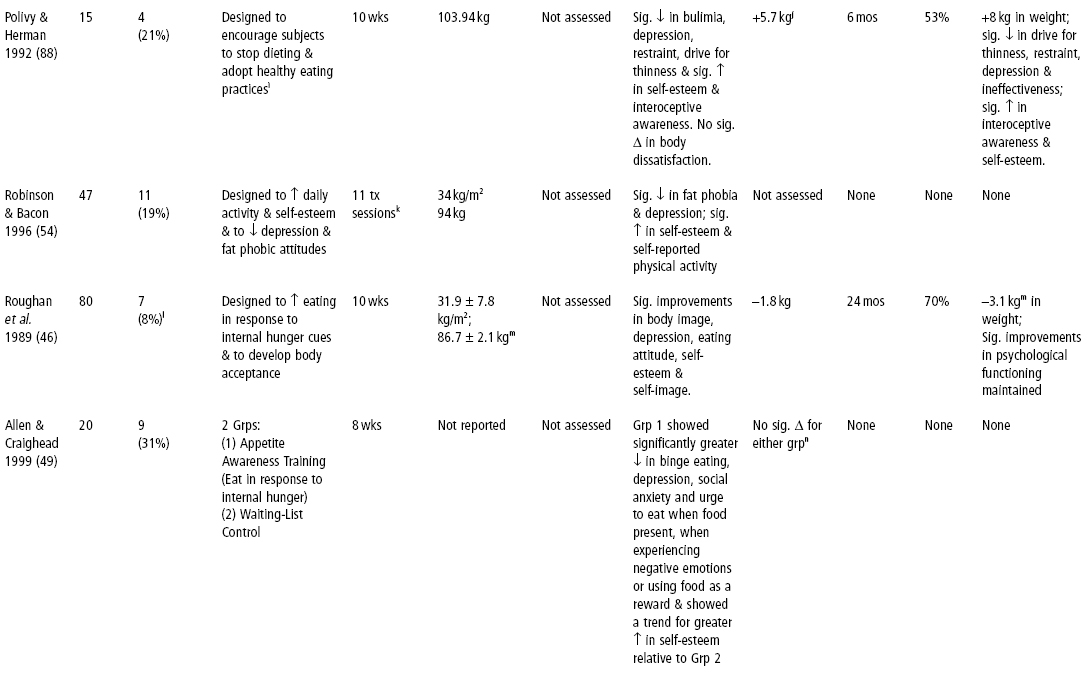

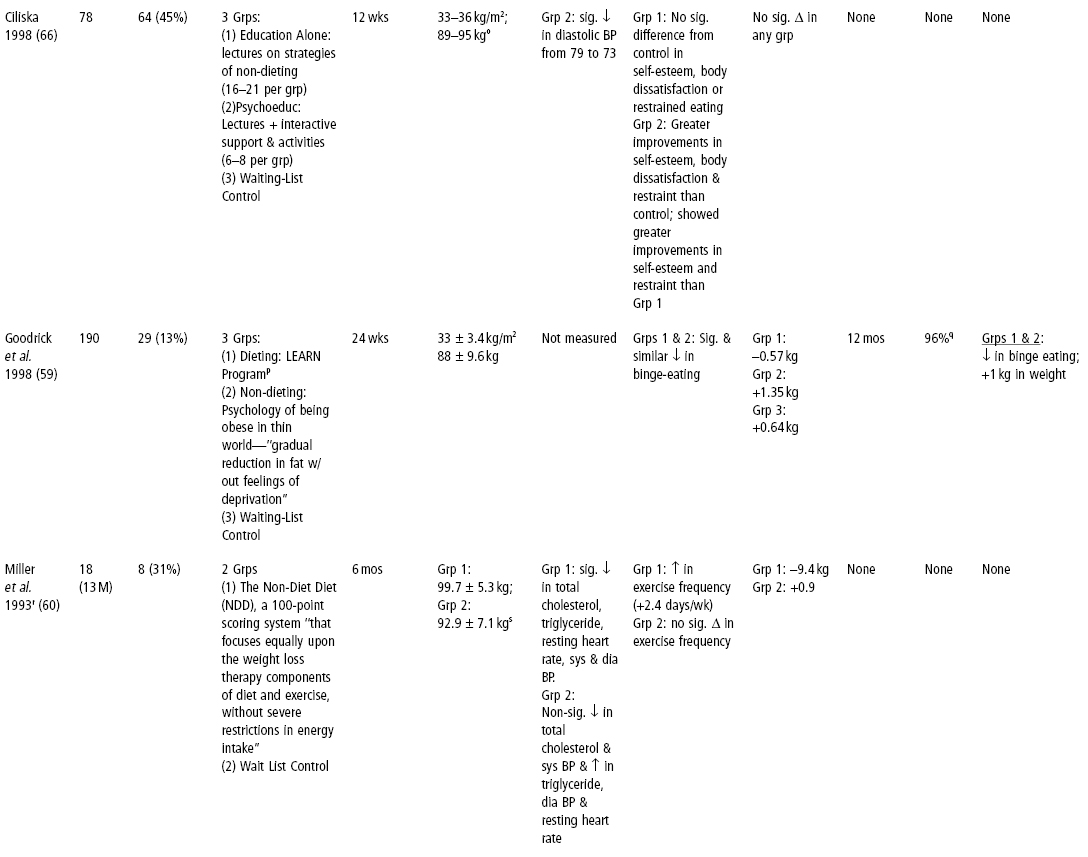

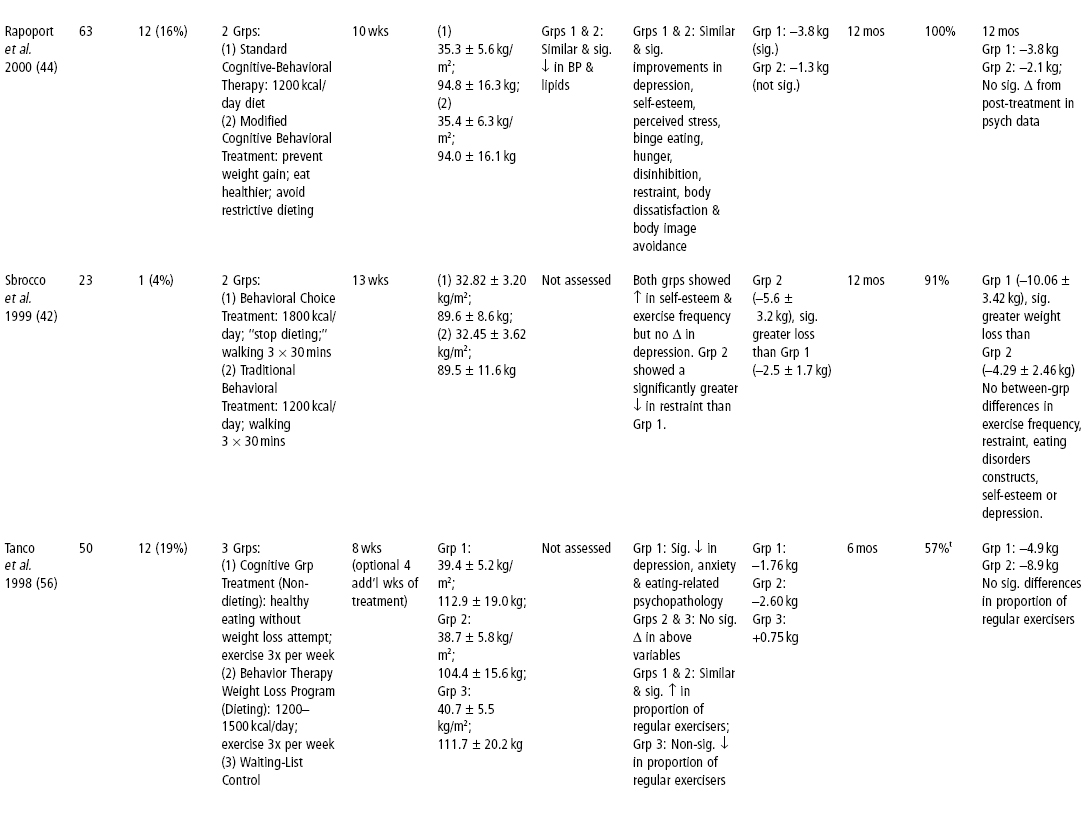

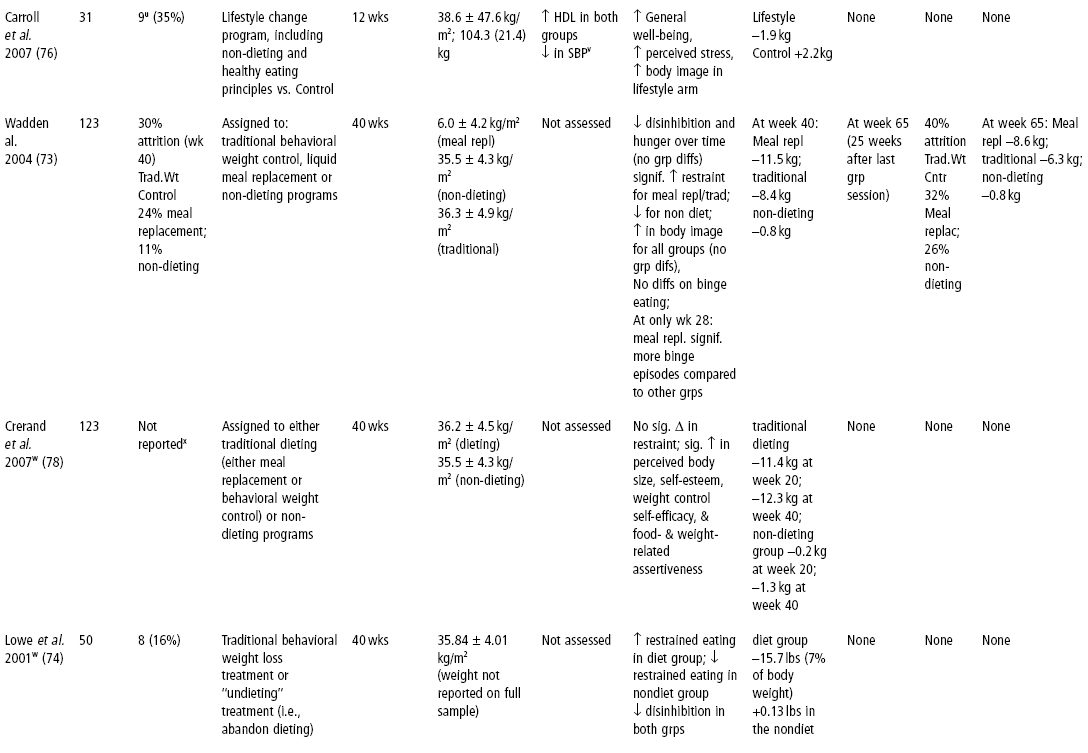

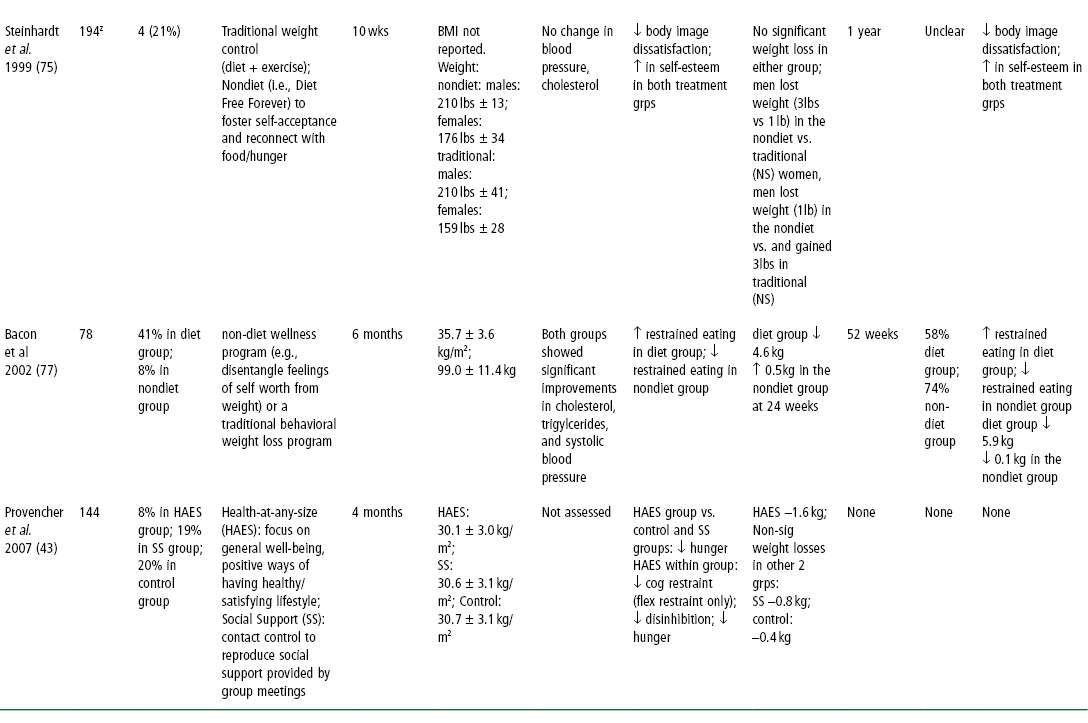

This section summarizes the scientific literature on non-dieting approaches. All of the studies published (to our knowledge) on non-dieting programs are summarized in Table 16-1. Representative studies are described in greater detail below. Studies that did not include stopping dieting as an explicit focus (e.g., 72) were not included.

Table 16-1 Published Studies on Non-dieting Programs

aOriginal number enrolled not defined; 79 completed pre- and 3-year follow-up questionnaires; 28 of 79 did not complete 26-week treatment program; 14 of 79 attended at least one follow-up meeting.

bBased on Hirschmann and Munter’s (13) “Overcoming Overeating” approach.

cWeights for both groups based on self-reports.

dMeasured ability to identify physiological vs. emotional hunger, ability to match hunger to a specific food, ability to identify an emotion associated with eating and extent to which one kept food accessible throughout the day.

e(1) Dropouts: didn’t complete 26-week program; (2) Participants: completed 26-week program; (3) Participants & Follow-Up: completed 26-week program and at least two follow-up activities.

fN = 13 for depression and BP data.

g4 dropouts; three completed treatment but did not complete follow-up—no data included.

h6-point Likert-type scale developed for this program assessing prevalence of chronic dieting (higher score indicated a “more independent, non-dieting lifestyle”).

iBased on Polivy & Herman’s Breaking the Diet Habit (16).

jN = 13.

kLength of treatment not reported.

lData collected on only 38 subjects at all five data points.

mN = 72 for BMI/weight data.

nNo data given.

oMean ranges for 3 groups.

pBrownell (55). LEARN Program for Weight Control.

qGrp 3 not included in 18 month follow-up; given treatment after 6 months.

rNo comparisons of control & experimental groups were directly reported.

sValues for Miller and colleagues (60) are means ± SEM.

tGrp 3 not included in 6-month follow-up.

uDifficult to judge attrition rate: 62 were in original study, while only 55 had metabolic syndrome and were included in sub-study. Only 20 completed the exercise testing at the start and end of the intervention.

vNo significant differences in fasting glucose, triglycerides, diastolic BP.

wBoth Lowe and colleagues (74) and Crerand and colleagues (78) examined a subset of participants from Wadden and colleagues (73).

xAttrition for this sample was reported in Wadden and colleagues (73): 30% attrition at week 40 for traditional behavioral weight control; 32% for meal replacement; 26% for non-dieting.

yOnly reported by group, not for aggregate.

zData also were reported on two additional groups (non-volunteer comparison group, those who chose not to participate in either treatment group; true control group). Only data on the traditional and non-dieting programs are presented here.

Descriptive Studies

First-generation studies of non-dieting programs were descriptive in nature (29, 36, 46, 50). These studies were helpful in collecting initial data about novel approaches, but provided no comparisons to traditional dieting approaches. In one of the first such studies, Roughan and colleagues (46) evaluated a 10-week non-dieting approach in 80 women (both overweight and normal weight) who were preoccupied with weight and eating. Participants lost an average of 1.8 kg and reported significant improvements in mood, self-esteem, and body image following treatment. More impressive was the fact that these changes were maintained at a two-year follow-up in the 56 women who were evaluated. Self-reported weight loss at two years was 3.1 kg.

Polivy and Herman (36) reported the results of a 10-week “undieting” program in 15 women who weighed an average of 104 kg. After treatment, participants showed improvements in mood, self-esteem, drive for thinness, and binge-eating, but did not experience improvements in body dissatisfaction. Among eight participants evaluated at a six-month follow-up, most improvements were maintained. There were no statistically significant changes in weight over the entire course of the program and at six-month follow-up.

Mellin and colleagues (52) evaluated a 12-week “Solution Method” program based on six developmental skills (strong nurturing, effective limits, body pride, good health, balanced eating, and mastery living). Of 29 subjects, 22 completed the first 12 weeks and were followed for two years. Mean length of participation was 18 weeks. Subjects lost an average of 4.2, 6.0, and 7.0 kg at months 3, 6, and 12, respectively. At the two-year assessment, participants had a 7.9 kg weight loss, a 109-minute per week increase in physical activity, and reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressure of 14 and 15 mmHg, respectively. Among 13 subjects who completed a depression inventory, there was a slight but non-significant improvement at two years.

Controlled Comparisons

Second-generation studies have employed randomized controlled trials to compare a variety of non-dieting approaches to traditional dieting programs and/or no treatment controls. These studies have examined a variety of outcomes including weight loss, binge-eating and eating pathology, mood and self-esteem, and metabolic outcomes. Findings from these studies are described in detail below.

Weight Loss

Weight outcomes have been examined in studies using a non-dieting paradigm. Wadden and colleagues (73) investigated whether dieting was a precipitating factor for binge-eating and other adverse behavioral consequences among 123 obese women. The women were randomly assigned to: 1) traditional behavioral weight control; 2) standard meal replacement; or 3) a non-dieting approach that discouraged calorie restriction, which included avoiding being hungry, eating all foods, including “bad” foods, and stopping eating when full. This study was unique in that it experimentally manipulated the degree of dieting. At week 20, weight loss as a percentage of initial weight was 12.1 ± 6.8% (meal replacement), 7.8 ± 6.0% (behavioral), and 0.1 ± 2.4% (non-dieting). At week 40, weight loss was: 11.5 ± 8.9% (meal replacement), 8.4 ± 8.7% (behavioral) and 0.8 ± 3.2% (non-dieting).

Lowe and colleagues (74) conducted a study with a subset of the women who were participating in the trial described above (73). By week 8, participants in the meal replacement arm lost approximately 7% of their weight, compared with no weight loss in the non-dieting treatment arm; there was an increase in cognitive restraint in the weight loss treatment group and a reduction in the non-dieting group (74).

Other studies have demonstrated less robust weight loss for non-dieting treatment groups (e.g., 44, 56, 75). One study found modest weight losses (1.6 kg) in a “health-at-any-size” intervention group compared with the social support and control groups (43). Another study (76) found non-significant weight loss among the non-dieting “lifestyle” intervention group (1.9 kg) compared with a gain in the waiting list control group (2.2 kg). Bacon and colleagues (77) assigned obese, female, chronic dieters to either six months of weekly group treatment in a non-diet wellness program or a traditional weight-loss program. Attrition was high in the traditional group (41%) compared with the non-dieting group (8%). Weight loss was observed at the one-year follow-up in the traditional treatment group only (5.9 kg), compared with −0.1 kg in the non-dieting group.

Binge-Eating and Eating Pathology

As mentioned previously, there has been some question as to whether dieting is a precursor to the development of eating pathology. In Wadden and colleagues’ study (73) described above, the meal replacement group reported more binge-eating episodes at one reporting time (week 28), but at all other time points (weeks 20, 40, 65) there were no significant group differences; at no time point did any participant meet criteria for binge-eating disorder. During this time, no significant differences were found among the groups regarding binge-eating episodes, reports of hunger, or disinhibited eating. It was concluded that the adverse effects of dieting (e.g., binge-eating) found in normal-weight dieters may be inappropriately generalized to overweight patients and should not deter overweight patients from attempting weight loss (73).

Lowe and colleagues (74) conducted a study using an eating regulation lab paradigm. By week 8 of the parent intervention (see 73), there was an increase in cognitive restraint in the weight loss treatment group in this sub-study and a reduction in the non-dieting group (74). After eight weeks of the intervention, a lab protocol was conducted; findings indicated that those participants who were actively restricting their food intake had a different pattern of eating regulation. Specifically, dieters ate more following a pre-load than the non-dieters. The authors suggest that the process of restrictive eating (or “dieting”) might create vulnerability toward counter-regulatory eating and potential increased susceptibility to overeating. Other studies also have found increases in cognitive restraint in the traditional diet group and decreases in the non-dieting group (42, 77), as well as decreases in susceptibility to hunger in a “health-at-any-size” intervention arm compared with the social support and control arms (43).

Two controlled trials have evaluated the efficacy of non-dieting approaches in the treatment of binge-eating disorder (49, 59). Goodrick and colleagues (59) compared a non-dieting approach, a dieting approach, and a wait-listed control. After six months of treatment, both the dieting and non-dieting groups showed significant and similar improvements in binge-eating. Allen and Craighead (49) compared an eight-week appetite awareness treatment, focused on responding to moderate signals of hunger and satiety, to a wait-listed control. At the end of treatment, the appetite awareness group showed significant improvements in binge-eating. These two studies suggest that non-dieting programs appear to have favorable effects on binge-eating, but not greater than those of traditional dieting treatments.

Mood, Self-Esteem, and Obesity-Related Attitudes

Studies of the non-dieting approach also have examined psychological factors (e.g., depression, self-esteem) and obesity-related attitudes. Studies have shown increases in self-esteem, mood, and body image satisfaction for both traditional weight control treatment and the non-dieting treatment (44, 75), while another study found that compared with the non-dieting group, mood improved significantly more in the traditional and meal replacement groups (73).

Crerand and colleagues (78) examined changes in obesity-related attitudes (e.g., “Obese people are as happy as non-obese people,” “Most obese people eat more than non-obese people”) among women who were part of the larger trial conducted by Wadden and colleagues (73). Crerand and colleagues (78) combined the data from the meal replacement and behavioral weight control groups, which were then compared with the non-dieting group. At both follow-up points, the non-dieting group reported improved attitudes toward obese persons, compared with the traditional group. The dieting group had greater improvements in depression; however, there were no significant differences between groups on body image or self-esteem, as both dieting and non-dieting groups improved on these factors.

Metabolic Outcomes

Some studies of the non-dieting approaches have examined metabolic outcomes, in addition to weight and psychological outcomes. Rapoport and colleagues (44) found small but significant improvements in blood pressure and total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol for both the traditional and non-dieting approaches. However, there were no differences between the groups at 12 months on any of these variables. In the study by Bacon and colleagues (77), participants in both the non-dieting wellness program and traditional weight-loss program showed significant improvements in cholesterol, triglycerides, and systolic blood pressure (only HDL cholesterol was significantly different between groups, with non-dieting subjects having lower HDL cholesterol). These findings are of interest as the non-dieting group did not lose a significant amount of weight, while the traditional treatment group lost 5.9 kg, with significant differences being found between the groups. Another study (76) found improvements in fitness, fasting HDL cholesterol, and diastolic blood pressure in both treatment groups, but improvements in global well-being, body image, and stress occurred in the non-dieting group only.

Limitations

Although these controlled trials have increased the fund of knowledge about non-dieting approaches, they are limited by short interventions, incomplete follow-ups, small samples, and high attrition. For example, about half of the randomized studies in Table 16-1 employed interventions ranging from 8 to 13 weeks. Similarly, six studies reported no follow-up data (43, 49, 60, 66, 70, 76), and others included only 57–74% of subjects at follow-up (49, 56). Furthermore, three studies had fewer than 25 subjects (42, 49, 60), and six had attrition greater than 30% during treatment (49, 60, 66, 76, 77).

Findings of the Research

Based on the available data, what can be concluded about the utility of non-dieting approaches? One consistent finding is that non-dieting approaches appear to have favorable effects on self-esteem. Faith and colleagues (79) performed a meta-analysis on six (mostly uncontrolled) studies and found effect sizes for self-esteem ranging from 0.67 to 3.79, which yielded a weighted mean d value of 1.57 (SE = 0.11). In other words, self-esteem was increased by approximately 1.6 standard deviation units—an extremely strong effect. There are consistent but not universal findings for improvements in mood and body image. Some studies found that psychosocial changes in non-dieting groups were similar to those in dieting groups (42, 44, 78), while others found greater improvements in non-dieting groups (56), particularly among attitudes toward obese people (78).

Among the few studies that assessed physiological variables (44, 52, 60, 66, 77), there were small but significant changes in blood pressure and lipids, although two studies (44, 77) found no difference between dieting and non-dieting groups. Interestingly, Ciliska (66) reported a decrease in diastolic blood pressure in the absence of weight loss.

Most non-dieting programs produce little or no change in body weight. The programs producing the larger weight losses are typically those that have incorporated some elements of traditional dieting (42, 60), with the exception of Mellin and colleagues (52). It is interesting to note that in some studies, weight loss continued in the non-dieting group during follow-up (42, 52)—a pattern quite different from that of traditional dieting programs. In summary, it seems reasonable to conclude that non-dieting programs favorably affect self-esteem, mood, and body image, but result in little change in body weight. The effects on medical outcomes are understudied, especially in controlled trials. Another approach may be to examine weight changes without calorie restriction. One study compared the effect of three exercise prescriptions on weight loss (with a specific instruction to participants not to diet) (70). This study found a dose response for weight loss with the group prescribed the high amount/vigorous-intensity exercise losing approximately 4% of their initial body weight, compared with approximately 1.2–1.5% in the low amount/vigorous-intensity and low amount/moderate-intensity, respectively, and a weight gain of 1.3% in the control arm.

A Critical View

This section assesses the relative strengths and weaknesses of non-dieting approaches, and suggests directions for future research and practice.

Strengths

A major strength of the non-dieting movement is its continued emphasis on the long-term ineffectiveness of conventional, dieting-based treatments. Although increased physical activity and continued patient–practitioner contact following treatment significantly improve the maintenance of weight loss in the year following treatment, weight regain is the most frequent long-term outcome of dieting (4, 22). This lack of long-term success for most persons should lead overweight persons to consider carefully the long-term benefits and risks of dieting before embarking on “another diet.” In addition, the lack of long-term efficacy should prompt healthcare professionals to develop alternative treatment approaches aimed at improving the health of overweight persons.

The need for alternative treatment approaches is highlighted in a review by Mann and colleagues (4). Unfortunately, multiple efforts to modify the dieting paradigm in some way have resulted in the same long-term result: weight regain. Clearly, there is a need for new approaches that are not based on the current dieting paradigm, and the non-dieting movement has provided one such alternative. There is continued debate in the field, as highlighted by articles (80, 81) published in the same issue as Mann and colleagues’ review (4). While a comprehensive overview of the issues is beyond the scope of this chapter, a few points are worth noting here. First, while Mann and colleagues (55) provide evidence for the lack of effectiveness of dieting, Powell and colleagues (81) reviewed studies of the multi-component behavioral interventions designed to promote sustained reductions in weight and found both lifestyle and drug interventions produced weight losses of approximately 3.2 kg that were sustained for at least two years and associated with improvements in diabetes, blood pressure, and CVD risk factors. In an attempt to reconcile these two apparently opposing reviews, Kaplan (80) makes an important distinction: Mann and colleagues (4) focused solely on studies of “dieting” while Powell and colleagues (81) included a broader scope of interventions for weight loss. It was suggested that dieting alone may not be the answer, but a multi-component approach including lifestyle change, surgery, or medicine may be the future of obesity treatment (80). This type of lifestyle approach was examined in the Diabetes Prevention Program, with 4% weight losses decreasing the risk of type 2 diabetes by nearly 60% (82).

Perhaps the greatest strength of the non-dieting movement is its affirmation of a person’s worth, no matter what he or she weighs. This message is so countercultural that it can seem ridiculous to suggest that obese persons should accept themselves or that overweight does not result from a lack of character or willpower. However, there are indeed many factors that influence body weight, some of which are not under one’s control (see Chapters 5–9). Overweight people are not weak-willed, lazy, or undisciplined; nor are they morally inferior or deficient in character. Such stereotypes are not only inaccurate but cruel, and like other forms of discrimination and prejudice, should not be tolerated. The non-dieting movement has provided a great service by promoting messages that encourage overweight persons to live life now, rather than waiting until they lose weight (65). In addition, these messages can prompt professionals to remember that, as members of our society, they are likely to have anti-fat attitudes that need to be identified and modified (83, 84).

Weaknesses

The most significant weakness of the non-dieting approaches is the lack of scientific support. It is troubling that non-dieting books and programs continue to proliferate, despite a dearth of studies demonstrating their effectiveness. No approach, no matter how well intentioned or sensible, should be marketed as effective when it has not been adequately studied. As for any other treatment, efficacy claims about non-dieting programs should be supported by well-conducted studies. Unfortunately, the proliferation of non-dieting books, videos, and clinic-based programs makes it difficult to distinguish these approaches from the multitude of new diet books and diet clinics that are also promoted without scientific evaluation. Overweight persons deserve better. They are entitled to know the short- and long-term results of alternative treatments so they can make informed decisions about their health and weight.

The non-dieting movement also suffers from a lack of empirical support for some of its basic beliefs. For example, it has been known for over a decade that the psychosocial effects of dieting and weight loss are typically, although not universally, quite positive among obese persons receiving standard cognitive-behavioral treatment, despite reports in the 1950s of adverse effects in normal-weight men and obese psychiatric patients (85). Yet non-dieting programs continue to conclude that dieting is universally harmful, based largely on laboratory assessments of normal-weight, college-age women classified as “restrained eaters.” These proponents have ignored the differences in the characteristics of various dieters, particularly whether the person is overweight or not (86), has rigid perceptions related to dieting (87), or shows cognitive restraint of eating (88). The effect of dieting on cognitive performance in obese women also has been shown to be limited (89), suggesting that dieting among obese women (compared with normal-weight women) might afford other benefits (e.g., well-being) that might mitigate cognitive impairments. Similarly, comprehensive reviews and investigations do not support claims that dieting leads to binge-eating or other eating disorders among obese individuals (90, 73). Non-dieting books often describe the harmful effects of weight cycling in unequivocal terms. The scientific literature reveals that some of the purported effects of weight cycling (e.g., decreased metabolic rate, increased body fat, depression) do not occur, while others (e.g., increased morbidity and mortality, psychological effects) are far from being clearly resolved (91–93).

Finally, the belief that weight is not a risk factor for disease is contrary to a large body of literature that has controlled for multiple mediating factors (22, 94) (see Chapters 1 and 12). Some data do suggest that health may be more influenced by fitness than by fatness (37, 39–40); it may be possible to be fit and fat. However, many Americans, both overweight and lean, are not fit. Thus, many overweight persons—the targets of most non-dieting programs—are at higher disease risk. It remains to be seen whether changes in weight or in fitness will be more effective in terms of health outcomes. In the absence of definitive data and the presence of substantial contradictory data, it seems misleading or even irresponsible to suggest that excess weight is unrelated to health. Whether increased risk is mediated by fat or fitness, obese, unfit people are at increased medical risk. Although psychosocial improvements are important in their own right, the lack of attention to reducing medical risk is troubling.

In addition, there is considerable evidence that weight loss among obese persons improves diabetes, glycemic control, hypertension, and dyslipidemia over 6–12 months (22, 82, 95). Although it is true that no studies have shown definitively that weight loss has long-term benefits on health, no such studies have been conducted. Most studies that have been reported about the effects of intentional weight loss were not designed to answer that question (96), and most rely on self-reports and/or retrospective recalls of weight, weight loss, and number of dieting attempts (4, 93). Among this flawed literature, some studies indicate that intentional weight loss has positive long-term effects, others show no or limited adverse effects on mortality (4, 41, 93).

A prospective randomized controlled trial is being conducted in 5,145 obese individuals with type 2 diabetes to address this critical question (97; see www.lookaheadtrial.org). In this trial, the goals are to induce weight losses of at least 7% and increase moderate-intensity physical activity to 175 minutes per week among overweight participants with type 2 diabetes by using a comprehensive, lifestyle intervention approach (98, 99). One-year results show clinically significant weight loss associated with improvements in diabetes control and CVD risk factors (100). Participants will be followed for up to 12 years to examine the effects of weight loss (and perhaps weight cycling) on cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality (e.g., myocardial infarction, stroke).

Similarly, although a large body of research suggests the importance of biological factors in the control of body weight, it is a mistake to minimize the role of environmental factors. The increase in the prevalence of obesity during the last decade cannot be explained by genetic factors. Clearly, biological and behavioral factors interact to influence body weight (101). Both should be considered when a person is attempting modest weight loss as a means to improve health.

Challenges

Given these strengths and weaknesses, the non-dieting movement, as well as the entire scientific community with an interest in the health of overweight persons, is faced with a series of challenges. We believe that non-dieting approaches merit further investigation in randomized controlled trials. In order to facilitate assessments of clinical utility, we make the following recommendations for future research.

The first is to define clearly what is meant by “dieting” and “non-dieting” treatments, since standard cognitive-behavioral approaches and non-dieting approaches for weight loss have more in common than might be thought (e.g., eating a variety of foods in moderation, consuming forbidden foods, increasing physical activity, limiting external cues to eating, self-acceptance). Such comparisons will be facilitated by the use of standardized treatment protocols for both non-dieting and dieting treatments. Critical issues to clarify will include the goals and methods of dieting and non-dieting approaches, as well as measurable outcomes to assess whether goals have been achieved. We agree with Parham (20) that each program should be assessed relative to its unique goals, but we add that such goals need to be made explicit and measurable.

Since a common goal of non-dieting programs is to stop dieting, it will be important to clearly define what is meant by “dieting.” This may mean going long periods of time without eating, avoiding “fattening” or “forbidden” foods, or following a specific eating regimen. It has been recommended that dieting “refers to the intentional and sustained restriction of caloric intake for the purpose of reducing body weight or changing body shape” (90, p. 2582). It is interesting to note that the word “diet” is derived from the Greek diaita, meaning “way of life.” The treatment of many other medical conditions (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, lactose intolerance, celiac disease, dyslipidemia) consists of dietary management that requires limiting or even eliminating certain types of foods to improve health. Overweight persons will need guidance about how to distinguish “dieting” from other methods of healthy eating/living.

Optimal interventions are likely to be at least six months in duration, especially for non-dieting programs that seek to challenge long-standing beliefs and behaviors relating to weight, eating, physical activity, self-esteem, and body image. Mastering the dialectic of acceptance and change can be quite challenging (102–103), and it is unlikely that sustained attitudinal and/or behavioral changes can be achieved with a few months of weekly meetings.

It would also be useful to include interventions that are variants on the dieting and non-dieting paradigms. It may be that some blending of approaches, as reported by Sbrocco and colleagues (42), will be helpful. This focus on individual health behaviors, rather than on weight and weight loss, is proposed by others who suggest that weight loss may not be advisable for someone who is overweight, but is physically active, has normal lipid and blood pressure values, and eats a healthy diet (37). Similarly, it may be useful to evaluate interventions that focus solely on improving fitness, with less concern about dieting or non-dieting.

A critical research issue will be the measurement of both physical and psychological indices of health. If health at any weight is the desired paradigm shift, both dieting and non-dieting programs must be compared on such risk factors as lipids, glucose tolerance, blood pressure, and fitness. Others have called for examining the effect of dieting itself on health outcomes and whether the health benefits afforded by short-term weight loss are sustained despite subsequent weight gain (4). Although changes in diet and physical activity may be interesting, the lack of valid assessment (without considerable expense) makes them less useful.

When investigators are reporting mean changes in physical and psychological variables, it is important to assess clinical significance. Reporting only mean values can obscure important information, such as changes in clinical status. For example, statistically significant changes in Beck Depression Inventory scores for a non-depressed sample (e.g., from 7 to 3) are much less meaningful than the percentage of patients who progressed from depressed to non-depressed categories. Assessing clinical significance will be enhanced by using reliable and valid psychosocial measures that have normative scores for clinical and nonclinical samples. This will allow readers to assess whether pre- and post-treatment values were in clinically significant ranges. Similarly, for physiological variables, it will be more important to report sub-analyses for patients who already have diabetes, dyslipidemia, or hypertension than for those who do not have such comorbidities.

In addition to the larger issue of relative efficacy, many other questions deserve research attention. For example, it is unclear whether non-dieting approaches are best suited for overweight persons who have never dieted, for those who have dieted and given up, for average-weight persons who have neither dieted nor become overweight, or for those at risk for eating disorders. It is possible that non-dieting approaches may be useful in the prevention of eating disorders and obesity. Thus, it may be better to teach people never to begin dieting than to teach them to stop dieting once they have begun.

A final challenge is to decrease the distance between dieting approaches typically used by professionals in the obesity field and non-dieting approaches typically used by those in the eating disorders field. This division has sometimes resulted in misunderstandings that can lead to hostility and hyperbole. In fact, some have argued that the media attention to obesity amounts to a “moral panic” and “impending disaster” (2). Overweight persons would be better served by active collaboration between the two fields. It is likely that the two fields will disagree about several issues, such as the effects of dieting and the ill effects of obesity. However, they are likely to agree about the long-term ineffectiveness of most dieting attempts, the value of enhancing body image and self-esteem irrespective of weight loss, the need to fight discrimination against obese persons, and the need to provide effective healthcare beyond weight loss for overweight patients. The public health agenda should focus on normalizing eating behaviors, as the drive for thinness creates conflicting emotions and behaviors for many individuals (6).

Conclusion

The development of non-dieting approaches continues to be a promising alternative in the care of overweight people. However, these approaches need careful, continued evaluation before being widely disseminated. Such information will help overweight people make informed decisions about managing their health and weight. Ultimately, whether the decision is to diet or not to diet, we hope that professionals can help overweight persons realize that weight is just one factor that describes them; it does not define them.

Summary: Key Points

- The three underlying assumptions of the non-dieting approach to weight control are that dieting is 1) ineffective; 2) harmful; and (3) longstanding beliefs about it are incorrect, such as the belief that obesity is harmful.

- The evidence that dieting is ineffective includes the fact that, over the long term, dieters regain the weight lost and some may eventually weigh more.

- The evidence that dieting is harmful is that it can undermine self-esteem, reinforce a distorted body image, lead to weight cycling, and increase the risk of disordered eating.

- The argument that obesity is not harmful rests on several claims. They include that a “third factor” that accompanies obesity is responsible for ill-health (e.g., repeated dieting, inactivity, lack of fitness, or smoking to suppress appetite); that a moderate degree of overweight diminishes the risk of osteoporosis and certain cancers; and that the evidence that weight loss improves health or reduces mortality is limited and contradictory.

- The five goals of non-dieting approaches are to increase awareness of the ill-effects of dieting, educate that body weight is biologically determined, increase responsiveness to physiological cues of hunger and satiety, improve self-esteem and body image by increasing self-acceptance, and increase physical activity.

- The major weakness of the non-dieting approach is the lack of scientific support for many of its basic tenets and the overlap of many of its goals with traditional diet programs that take a comprehensive approach to lifestyle change.