Noninvasive Diagnostic Work-up

A diagnostic work-up always begins with the medical history and a clinical examination of the patient. However, the latter remains very subjective and is very much dependent on the examining physician. Gait and neuropsychological tests can objectify and grade the symptoms and make these comparable during follow-up as well as with other patients. Of course, imaging is also essential in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH) and is described in Chapter 7.

“There is no accepted standard for this topic” is a statement from guidelines that address iNPH,1 and it is also valid for the diagnostic work-up of iNPH. Multiple tests for walking, balance, and neuropsychological evaluation (fewer for incontinence) are available; however, there is no common agreement about which test is most relevant for diagnostic purposes and which test is best for determining treatment efficacy. Because gait disturbances react more extensively and more quickly to spinal tap tests and shunting than do incontinence and dementia, gait tests are of high clinical importance when evaluating the efficacy of diagnostic spinal tap tests and shunting.

Various tests are applied in different departments, thus making comparisons very difficult. Many tests are extremely time-consuming, which result in restrained performance in daily routines. However, for scientific evaluations, it is worthwhile to perform them because they will enable us to learn more about their relevance in iNPH as well as about the condition itself. Some tests seem to show only general deviations from normal, whereas others may show iNPH-specific changes. Several tests can be performed only in patients who are able to collaborate sufficiently. It is obvious that gait tests require certain mobility and neuropsychological tests require certain cooperation, thus excluding the testing of patients with severe dementia.

Normal values for diagnostic tests are often critical because they are for otherwise healthy patients without comorbidities: What is the normal walking speed for a patient aged 80 years with coxarthrosis or Parkinson disease? What are the normal values of psychometric tests if the patient also has Binswanger disease? Even with these tests, it is still important to follow up with individual patients to evaluate diagnostic and therapeutic efforts.

Symptoms are often subtle and differences are not easily detected even on using sophisticated tests. Therefore, reports from the patients, and from their relatives who witness the everyday life of the patients, must be considered. This information plays a special role during follow-up when objective measures cannot demonstrate any substantial difference.

The diagnostic work-up is based on the patient’s medical history, and complete clinical examination with an assessment of gait disorders, incontinence, and mental impairment.

6.1 Evaluation of the Patient’s Medical History

As with any disease, a complete medical history is necessary. If normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) is suspected, then questioning must go into more detail providing exact description of the symptoms. Patients and/or their relatives should describe the symptoms and complaints. Ask about any urinary problems because patients often do not mention them because of a sense of shame. In addition, the neuropsychological situation should be evaluated; it is here that an interview with the patient’s relatives is of great importance because they might perceive behavioral changes, memory, and concentration–attention disturbances that are different from those reported by the patient. As the disease becomes more advanced, especially when dementia develops, further information from relatives is very important. Ask about minor symptoms of NPH such as headache, dizziness, and an increased need of sleep, among others. The physician must also check differential diagnoses and comorbidities.

6.2 Clinical Examination

The clinical examination of the patient should concentrate on the typical NPH triad, with an exact description of the clinical findings. These should be completed by gait and neuropsychological tests to quantify the deficits. A selection of widely used tests, with short comments relating to their clinical value and practicability, is presented below.

6.2.1 Evaluating Gait Disturbance

Gait disturbance is the most important clinical feature of iNPH and the symptom with the best prognosis after treatment. Substantial improvement is often observed only hours after a spinal tap test. Therefore, gait is not only a sensitive marker of the severity of NPH, but it also serves as a sensitive marker of the efficacy of the spinal tap test and shunting. Deteriorations in gait during follow-up may trigger a new investigation for suspected shunt failure. Thus, this emphasizes the importance of a good description of the gait disturbance as well as quantification and scoring.

Gait Description

The physician may describe the gait as slow, broad-based, atactic, and shuffling (see Section ▶ 6.2.1). A description such as this should raise suspicion of NPH and a description should always be present in the patient chart. However, a description alone is subjective and not sufficient to detect slight differences (i.e., after a spinal tap test). In addition, it is very much dependent on the examining physician and is difficult to compare with descriptions from other examiners. Therefore, it must be described using tests that make the gait disturbance measurable and comparable. A selection of tests and gait discriptions are presented below.

Step Length

One way of measuring step length is a description of the length of steps compared with the length of a patient’s foot (e.g., step length = one-half of foot length). It is a more objective parameter than the verbal description. However, it may vary substantially, and therefore it can be accepted only as a supplement for other tests.

180°/360° Turn

The patient is asked to turn 180° or 360° with as few steps as possible; normal values: 2 to 3 steps for 180°, 4 to 5 steps for 360° turn. If the patient understands this task, then it is an easily reproducible, quickly performed test that is good for use during follow-up, and is independent of the physician.

Gait Speed (10 m)

The time (and steps) needed to cover a distance of 10 m (marked on the floor) with normal walking is measured. It is a good reproducible parameter, but it is difficult to perform in some places (e.g., there is not always enough space).

Timed Up-and-Go Test

The sitting patient is asked to get up from his or her chair, walk 3 m, turn, go back to the chair, and sit down again. Normal time: <10 seconds. This is a complex task with different actions; it is reproducible, and superior to determining gait speed only.2

Video Recording of Normal Gait, Turn, or Timed Up-and-Go Test

Walking and different tasks are recorded on video, so that determinations can be repeated indefinitely, and analyses can be performed later, as well as time measurements for the different recorded tasks.

It is worthwhile to perform a video recording, especially for detecting subtle differences in gait after a spinal tap test or after treatment. It is reproducible and provides an opportunity to demonstrate the effect of a spinal tap test or shunting to others, independent of the physician. The disadvantage is that it is a time-consuming procedure; however, it is very reliable.

The routine video recording of a timed up-and-go test is desirable for all patients. However, if no sufficient time is available in daily clinical routine, the turn, gait speed, and the timed up-and-go tests are valuable and reliable tests for gait evaluation.

6.2.2 Evaluating Incontinence

The task of the physician is to obtain an adequate medical history of urinary problems despite the fact that the patient might feel a sense of shame. In particular, the physician must ask about pollakiuria, urgency, and incontinence, as well as fecal incontinence, as information about these is necessary to detect bladder and bowel problems.

Neurological and urological examinations should rule out other causes of incontinence such as cauda equina syndrome, urinary tract infection, and others.

6.2.3 Neuropsychological Testing

There are a variety of neuropsychological tests available, and there are many modifications of the original tests performed in clinical work. However, there is no general agreement as to which is the best test for identifying, measuring, and following up mental disorders. Intensive neuropsychological testing is time-consuming and not practical for routine use in a hospital. However, for scientific purposes, it is worthwhile to perform extensive testing with the aim of learning more about the neuropsychological pathology of iNPH. In addition, relevant and suitable items of neuropsychological tests could be developed for shorter routine tests.

For routine testing in a multicultural/multilinguistic environment, language-independent tests or multilingual tests are needed, so that some patients are not excluded. A neuropsychological expert is often not available; therefore, testing should be sufficiently easy for general physicians to perform the neuropsychological work-up.

The widely used mini mental state examination (MMSE; see below) is often performed in patients with iNPH; however, it “measures” cortical dementias rather than subcortical dementias (as is the case in iNPH) and is, therefore, less specific for iNPH. Nevertheless, patients with NPH perform significantly worse in the MMSE than healthy individuals and show significant improvement after shunting.3,4 Other psychometric tests may be even more selective when detecting deficits in iNPH (e.g., simple reaction time, the grooved pegboard test, the Stroop test, the digit span test, the trail-making test). For the MMSE, reaction time, grooved pegboard, digit span, Rey auditory verbal learning, and Stroop tests, patients with iNPH perform significantly worse compared with healthy individuals, and they show a significant improvement after treating iNPH with a shunt.3,4 Indeed, there are also many other and potentially more suitable tests; however, the aforementioned tests represent examples of tests that are relatively easy to perform and have the opportunity to be widely used in patients with iNPH. Below is a (small) selection of tests for NPH that can be performed by health care professionals; descriptions of these tests can be found in ▶ Table 6.1.

Test | Time required for completion (min)a | Validity for NPH | Feasibility in daily routine |

MMSE | 10–15 | + | ++ |

Grooved pegboard test | 5–10 | + | ++ |

RAVLT | >30 | + | – |

Digit span test | 5–10 | + | ± |

TMT | 10 | ± | + |

Stroop test | 10 | + | + |

Abbreviations: MMSE, mini mental state examination; NPH, normal pressure hydrocephalus; RAVLT, Rey auditory verbal learning test; TMT, trail-making test. aIncluding time required for patient instruction. | |||

Mini Mental State Examination

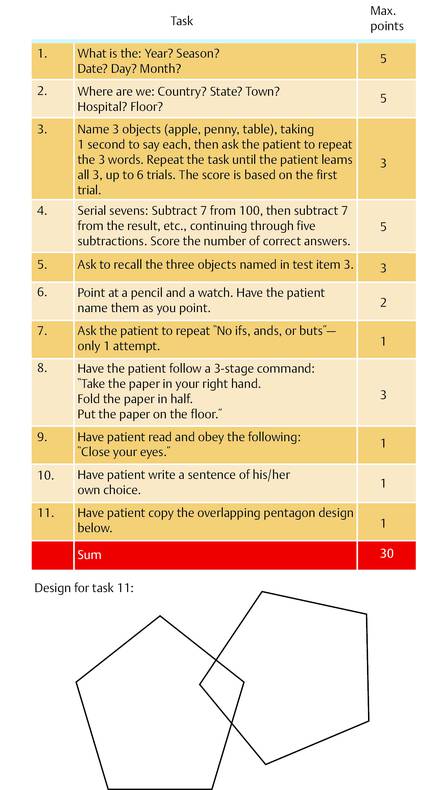

The MMSE is probably the most popular neuropsychological test, and is described by Folstein et al. 5 It screens cognitive impairment and assesses orientation in time and place, attention, concentration, calculation, language, short-term memory, and the ability to perform easy tasks (▶ Fig. 6.1). The test is also available in a number of different languages.6

Fig. 6.1 Mini Mental State Examination. A score of 30 indicates normal cognition, a low score indicates severe cognitive impairment. The performance of the MMSE test may be influenced by other diseases, especially by depression. Modified from Strauss et al.6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree