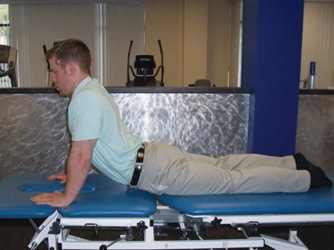

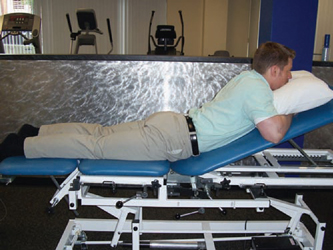

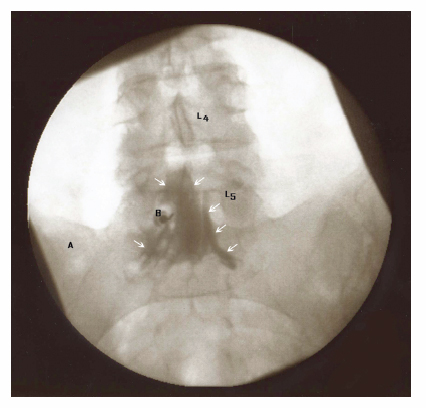

9 Nonsurgical Treatment of Herniated Nucleus Pulposus April Fetzer and Daphne R. Scott Most cases of herniated nucleus pulposus (HNP) respond favorably to nonoperative treatment. This is because the natural history of the HNP is quite favorable regarding resolution of symptoms over time. Approximately 80% of patients have full improvement of symptoms within 6 weeks of onset, and 90% of patients show improvement within 12 weeks.1 Most HNPs diminish in size over time, and 80% decrease by 50% or more.1,2 Accepted indications for proceeding with nonoperative treatment of the HNP include the absence of a progressive neurologic deficit and cauda equina syndrome.1 It is generally accepted that nonoperative management of the HNP may help avoid unnecessary surgery in many patients. Favorable outcomes for nonoperative treatment include the absence of pain on crossed straight leg raise, the absence of lower extremity pain with spinal extension, the absence of spinal stenosis on MRI, previous favorable response to steroids, the absence of a workman’s compensation claim, a motivated and physically fit patient, and a normal psychological profile.3 The goals of nonoperative treatment are to educate patients, to relieve pain, to improve function, and to prevent chronicity of the problem. Nonoperative treatments for the HNP include medications, bracing, physical therapy, and epidural steroid injections. Usually one, or any combination of the noted treatments, is applied to the patient with HNP. Each treatment option will be discussed and evaluated in this chapter. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are a first-line treatment for the pain associated with the HNP. Both cyclo-oxygenase (COX) inhibitors, COX-I and COX-II, play a role in alleviating pain associated with inflammation. In the United States, however, current use of COX-II is limited to celecoxib secondary to cardiovascular side effects.4 Although there are no studies on NSAIDs specifically in patients with HNP, NSAIDs have been found to be more effective than placebo for relieving pain. Evidence exists to support NSAID efficacy when compared with placebo for chronic low back pain (LBP).5 Steroids are typically prescribed either by oral, intramuscular, or injection routes1 for pain associated with the HNP. They are indicated for short-term use for alleviation of pain associated with radiculopathy.4 Although steroids are considered the standard of care, there are limited studies to support oral steroid use in this patient population. One published study on oral dexamethasone use reported no superiority to placebo for acute or long-standing pain, but did help patients with a positive straight leg raise alleviate pain.1 Two studies on intramuscular injection revealed no benefit versus a modest benefit for pain relief.4 Injection routes will be explored later in this chapter. Acetaminophen has been found to be efficacious for mild to moderate pain.4 It is safe, inexpensive, and sold over the counter. To avoid liver toxicity, the dosage limit is no more than 4 grams per day. Tramadol is a centrally acting analgesic that has a weak effect on monoamine oxidase receptors.4 Studies have shown that tramadol has improved pain control over placebo.5 Neither acetaminophen nor tramadol has been specifically studied for pain control in patients with HNP. Opioids are used to treat pain associated with acute or chronic radiculopathy, but there are no trials evaluating efficacy in patients with HNP.1 Opioids are not recommended beyond a short period for first-line treatment secondary to addictive potential.4 In general, opioids have been shown to be effective in relieving pain in patients with chronic LBP.5 Muscle relaxants may be used for patients with acute LBP, but like other medications, there are no studies on their effectiveness for HNP or radiculopathy.1 It is thought that muscle relaxants may have additional benefits when used in combination with NSAIDs.4 One high-quality study reported a significant difference between tetrazepam and placebo.5 Although antidepressants are not recommended for routine use in patients with acute LBP, there is moderate evidence for the efficacy of tricyclic antidepressants in patients with chronic LBP.4,5 Antiepileptics such as gabapentin or pregabalin may be helpful in treating neuropathic pain associated with radiculopathy, but these medications are not currently U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for this indication. Like other pain medications, there are no specific trials to support either antidepressants or antiepileptics for the specific treatment of the HNP. There is limited evidence to support the use of lumbar corsets in patients with LBP.1 Bracing is not thought to improve lumbosacral biomechanics or enhance dynamic lifting capacity, and its use is controversial.4 Nonsurgical management of patients with LBP accounts for nearly half of all patients receiving treatment in outpatient physical therapy centers.6,7 Traditionally, investigations of rehabilitation for low back disorders have demonstrated a dissension among rehabilitation approaches; a wide variety of treatment interventions are currently employed.8,9 Currently, patients with LBP are seen as a homogeneous group and thus are treated similarly. No uniform identification of patient subgroups exists. For example, patients with LBP secondary to HNPs who may require individualized and specific treatments are not separated from patients with LBP secondary to other causes, such as degenerative disc disease.10–15 Difficulty in grouping patients based on pathoanatomic mechanisms, such as the HNP, is also difficult. A treatment-based classification system has been developed, which has demonstrated favorable results over a nonclassification-based approach.16 The system classifies LBP patients into “specific exercise,” “manipulation,” “stabilization,” or “traction treatment” groups. Patients with HNPs fall into the “specific exercise” treatment group. Within this group, the basic clinical criteria for classification include patient preference for a specific position or movement and the ability to centralize distal extremity symptoms to the spine. Specifically, the physical therapist is able to obtain “centralization” by utilizing specific motions, either flexion or extension, of the lumbar spine.17 Centralization itself refers to a phenomenon where patients’ symptoms progress proximally from the distal extremity to the spine.18,19 Rehabilitation of the patient subgroup who centralizes symptoms with extension movement of the lumbar spine is addressed in this section. McKenzie originally observed the centralization phenomenon in 1959; he published his book on the mechanical standardized assessment and treatment of this patient group in 1981.19 This system of assessment and treatment may also be referred to as mechanical diagnosis and therapy. Operational definitions have varied as to the time and place when centralization occurs within the mechanical assessment and intervention of the patient. As detailed above, however, it is generally accepted that centralization occurs when the symptoms move from a distal location in the extremity to a more central location in the extremity or in the spine with specific end-range movement.20 Specifically, end-range extension movement of the lumbar spine (Fig. 9.1) has been found to relieve lower extremity symptoms in specific patient populations presenting with radicular symptoms.21–27 Recognition of centralization of symptoms in patients with HNPs provides physical therapists with the ability to classify patients for individualized treatment, as opposed to following traditional or general guidelines. Supporting evidence for the use of specific exercise in this patient population is emerging.28,29 The most common lumbar motion used with patients in the McKenzie-based “specific exercise” classification group is end-range lumbar extension (Figs. 9.1 and 9.2). Extension-based treatments have been studied with the greatest frequency in the literature. The study by Long26 included 230 patients with LBP and/or sciatica. Subjects were randomly assigned to receive exercises either matching or not matching their directional preference for centralizing symptoms. Eighty-three percent of the patients reported a directional preference of extension and a significant difference was observed for functional outcome between the matched and nonmatched groups. Petersen et al30 also studied patients with chronic LBP with or without sciatica and using an extension-based protocol. Short-term outcomes favored the extension-based protocol group. Browder et al28 also found better results in those patients that centralized with extension in a group that received mobilization along with extension-based exercise. Fig. 9.1 Active prone press-up with end-range lumbar extension. Fig. 9.2 Passive lumbar extension. The clinical relevance of centralization occurring within a patient population is 2-fold. The physical therapist may benefit by choosing the correct movements or mobilization/manipulation approaches to optimize the patient’s rehabilitation program. In addition, centralization has been identified as a prognostic indicator for recovery within the HNP population. It is predicted that 47 to 87% of patients with radicular symptoms will demonstrate full or partial centralization of their symptoms.31 Centralization has also been correlated with good and excellent overall functional outcomes, increased return to work rates, and less health care utilization.20,24–27 In combination with a comprehensive rehabilitation program, treatment-based classification subgroups and therapists’ utilization of extension-based McKenzie centralization techniques, yield the best outcomes for the HNP patient population. In 1958, Mixter and Barr32 first proposed that sciatica or radicular symptoms stemmed from the intervertebral disc. Epidural injections were first used in 1901 when cocaine was injected for treatment of lumbago and sciatica.33 The epidural steroid injection (ESI) became popular in the 1950s, when it was used for the treatment of sciatic pain.33 Today, epidural steroid injections are indicated for the treatment of spinal pain with radiculopathy and are best used in combination with an appropriate physical therapy regimen.33 The mechanism of steroid efficacy is to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, impair cell-mediated and humoral immune responses, block nociceptive C fibers,34 stabilize cell membranes, inhibit neural peptide synthesis, and suppress neuronal discharge, as well as to suppress sensitization of dorsal horn neurons.4 Clinical trials have shown ESIs to be more effective than control for acute radiculopathy,1 although they do not change the rate at which the HNP regresses. The ESI has both diagnostic and therapeutic benefits.33 Diagnostically, the injection can help identify the individual level or nerve root involved; therapeutically, the injection can provide pain relief from inflammatory mediators. Overall, the role of ESIs is to lessen radicular pain earlier than what would be seen with natural history alone.3 The optimal timing of an ESI is unknown.33 Because it is more invasive than other more conservative treatments such as NSAIDs or physical therapy, the treating physician may wish to wait until the patient has failed other treatments before prescribing the ESI. If given early, however, the ESI has the benefit of controlling inflammation, and preventing chronic problems like nerve fibrosis.33 In addition, the typical three-injection protocol is no longer in favor in the medical community. Rather, current protocols are to give ESIs one at a time, and only repeated when indicated for continued pain associated with radiculopathy. A third ESI may not be indicated when a patient does not respond to the first or second injection. ESIs should be performed by a fellowship-trained physician under fluoroscopic guidance. This will reduce complications and ensure proper needle placement, safety, and accuracy.4,33 Clinical trials have shown a “miss rate,” in which material is not delivered to the epidural space, of ~30 to 40% when performed blindly, even by experienced clinicians.33 Additionally, the use of contrast enhancement under fluoroscopy ensures that a high concentration of medication reaches the nerve-disc interface.34 Complications of ESIs are rare when performed by an experienced injectionist. They include headache (whether or not related to dural puncture),35 dural puncture, spinal cord injury, epidural hematoma, epidural abscess, discitis, aseptic meningitis, arachnoiditis, conus medullaris syndrome secondary to subarachnoid placement, and retroperitoneal hematoma.4,35,36 There have been no major complications in 1035 patients on antiplatelet treatment.34 A transient worsening of symptoms has been reported in —4% of patients within 24 hours of injection.33 Contraindications for ESIs include systemic or local infection; bleeding disorder; anticoagulation; allergy to steroid, anesthetic, or contrast; patient refusal; and uncontrolled diabetes mellitus (relative contraindication).33

Medications

Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs

Steroids

Nonopioid Analgesics

Opioid Analgesics

Muscle Relaxants

Adjuvant Pain Medications

Bracing

Physical Therapy

Epidural Steroid Injections

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree