Normal Sexual Function

Roy J. Levin

Introduction

Normal sexual function means different things to different people. It is studied by a variety of disciplines: biology, physiology, psychology, medicine (in the domains of endocrinology, gynaecology, neurology, psychiatry, urology, and venereology), sociology, ethology, culture, philosophy, psychoanalysis, and history. There is often little liaison or cross-fertilization between these disciplines and each has its own literature and terminology. Some are regarded as ‘hard science’, suggesting hypotheses that can be supported or rejected by experiment, observation, or measurement (evidence-based). Others are looked on as ‘soft science’, where individual and anecdotal evidence are the norm and are encouraged.

As space is limited, this chapter will characterize ‘normal sexual activity’ in the Western world mainly from biological, physiological, and psychological aspects but will occasionally utilize other disciplines when they yield insights not available from the ‘harder sciences’.

Biological determinants of normal sexual function

Humans are the highest evolved primates. A number of our anatomical/biological features unrelated to reproduction have been described as strongly enhancing our sexual behaviour when compared with other primates,(1) although recent studies have shown that the bonobos (pygmy chimpanzees) also use sex for reasons unconnected with reproduction.(2)

In brief, these features are as follows:

1 The relative hairlessness of our bodies allows well-defined visual displays (see point 6 below) and enhanced tactile skin sensitivity.

2 The clitoris, which is an organ whose sole function is for inducing female sexual arousal/pleasure.

3 Orgasms, in both male and female, provide intense euphoric rewards for undertaking sexual arousal to completion. The female is able to have multiple serial orgasms.

4 The largest penis among primates, whether flaccid or erect, the latter acting as a good sexual stimulator of the female genitalia.

5 Concealed (cryptic) ovulation which could influence males to undertake coitus more frequently to create pregnancy and prevent cuckolding.

6 Well-defined visual sexual displays in the female that are not linked to season or fertility (i.e. breasts, pubic hair, buttocks, and lips). The everted mucous membranes of the lips serve both as a surface display (red, moist, and shiny), and for haptic stimulation during kissing and sucking.

7 Ability of the female to undertake sexual arousal and coitus independent of season, hormonal status, or ovulation. Human females (unlike other primates) can and often do willingly partake of sexual activity and coitus when they are menstruating, pregnant, or menopausal.

8 Development of large mammary glands during puberty which act as visual sexual signals in most cultures.

These biological determinants are augmented by socio-cultural factors:

1 Language, art, and music for erotic stimulation.

2 Facial adornment with make-up to heighten appearance and sex displays (viz., lipstick).

3 Clothing, especially of the female, such as brassières to redefine the shape of breasts, corsets to redefine the shape of the body, and high-heeled shoes to elongate the legs and thrust out the

buttocks. Young adult males use tight trousers to create a genital ‘bulge’ and to emphasize firm rounded buttocks, the latter being a highly sexually attractive feature to young women.

4 Perfumes and scents to enhance body aroma.

The last three features (2, 3, and 4) use artificial means to enhance normal sexual signals.(1) These biological and socio-cultural factors give human sexual activity an increased appetitiveness and make it more rewarding.

Sexuality as a social construct and the concept of sexual scripting

Laqueur(3) suggests that while the sexual biology remained unchanged, its expression has been influenced over the centuries by culture, social class, ethnic group, and religion. This concept, that human sexuality is a social construct, has been strongly argued by Foucault(4) and promoted by other social constructionist authors.(5) Gagnon and Simon(6) introduced the concept of ‘sexual scripting’. Scripts organize and determine the circumstances under which sexual activity occurs, they are involved in ‘learning the meaning of internal states, organizing the sequences of specific sexual acts, decoding novel situations, setting limits on sexual responses and linking meanings from non-sexual aspects of life to specifically sexual experience’. Money(7) employed a similar construction in his development of ‘love maps’ for the individual. While patterns of behaviour are influenced by society and social forces, there is a dearth of evidence to show that sexual identity, orientation, or sexual mechanisms are also influenced.

Modelling normal sexual function—(i) the sex survey

One obvious way of describing normal sexual function is to ask people what they do. Two classic sex surveys were conducted by Kinsey and his coworkers who reported the results of interviews with 12 000 males in 1948(8) and 8000 females in 1953.(9) Their technique of sampling was to interview everyone in specific cooperating groups (clubs, hospital staff, universities, police force, school teachers, etc.). This gave samples of convenience but not a valid statistical sampling of the population. Despite their age and faulty sampling, however, there are still useful data in these surveys. In the sexual climate of the 1950s many of the findings were regarded as highly controversial. Clement(10) has reviewed the subsequent studies of human heterosexual behaviour up to 1990.

Surveys give a selective picture of sexual function. Results depend on the formulation of the questions, they rely on self-reports, and they represent only those prepared to describe their sexual behaviour. It is known, for example, that females tend to under-report their premarital sexual experiences(11) while males tend to overreport their lifetime partners.(11) Berk et al.(12) studied the recall by 217 university students of their sexual activity over a 2-week period assessed by questionnaires answered 2 weeks after the recording period, and by daily diaries kept over the same 2 weeks. Subjects reported more sexual activity in the questionnaires than in their diaries. Women reported giving and having more oral sex than the men. Clearly, data from questionnaire surveys should be treated cautiously.

A survey tells only what is frequent and not necessarily what is normal, but the most frequent practices often become identified with normal sexual behaviour. Surveys also vary in the range of behaviours that are asked about, for example coitus without condoms is important in the age of AIDS. Surveys have one great disadvantage, the facts that they produce are often ‘perishable’; many aspects of the sex surveys of the pre-pill era, or more recently the pre-AIDS era, are now of use only in a historical or comparative basis.

Two recent well-organized surveys based on samples of the whole population have been undertaken, one in the United States and the other in the United Kingdom. Interestingly, in both surveys, questions about masturbation were disliked by the respondents. In the American survey these questions were asked in a separate self-administered questionnaire, while in the British survey they were abandoned.

The American survey(13) was conducted face to face with 3159 selected individuals who spoke English in representative households by 220 trained interviewers (mainly women). Nearly 80 per cent of the individuals chosen agreed to be interviewed. Men thought about sex often, more than 50 per cent having erotic thoughts several times a day, while females thought about sex from a few times a week to a few times a month. The frequency of partnered sex had little to do with race, religion, or education. Only three factors mattered: age, whether married or cohabiting, and how long the couple had been together. Fourteen per cent of males reported having no sex in the previous year, 16 per cent had sex a few times in the year, 40 per cent a few times a month, 26 per cent two to three times a week, and 8 per cent four times a week. The percentages were similar for women. The youngest and the oldest people had the least sex with a partner; those in their 20s had the most. Of the women aged 18 to 59 years, approximately one in three said they were uninterested in sex, and one woman in five said sex gave her no pleasure. Unlike frequency, reported sexual practices do depend on race and social class. Most practices other than vaginal coitus were not very attractive to the vast majority. In women aged 18 to 44 years of age, 80 per cent rated vaginal coitus as ‘very appealing’ and an additional 18 per cent rated it as ‘somewhat appealing’. Among men 85 per cent regarded vaginal coitus as ‘very appealing’. The most appealing activity second after coitus was watching the partner undress, and this was appealing to more men (50 per cent) than women (30 per cent). This reflects the greater voyeuristic nature of men and their willingness to pay to look at women undressing or undressed.

In regard to oral sex, both men and women liked receiving more than giving. This practice varied markedly with race and education, with higher reported rates among better educated white people than among less educated and black people. Some 68 per cent of all women had given oral sex to their partner and 19 per cent experienced active oral sex the last time they had intercourse. Seventy-three per cent of all women had received oral sex from the partner, and 20 per cent had received it the last time they had had intercourse. Corresponding experiences were reported by men.

This survey, unlike many earlier ones, asked about anal sex. Of females aged 18 to 44, 87 per cent thought it not at all appealing, and only 1 to 4 per cent thought it very or somewhat appealing. In males of the same age 73 per cent thought it not at all appealing and rather more than women thought it very or somewhat appealing. Similar reports were obtained from women and men aged 44 to 59.

Regarding masturbation, older people (over 54 years old) had lower rates than at any other age, indicating that they do not use masturbation to compensate for an overall decrease in sexual activity with their partners.

In the United Kingdom survey,(14) 18 876 people were interviewed by 488 interviewers (of whom 421 were women). The sampling used one person per address and the acceptance rate was 71.5 per cent. Questions were asked about the frequency of vaginal coitus, oral sex, and anal sex, but not masturbation. The median number of occasions of sex with a man or woman was five times a month for females aged 20 to 29 and males aged 25 to 34, but declined to a median of two per month for males aged 55 to 59. More than 50 per cent of the females in the 55 to 59 age group reported no sex in the last month, but in this age group females are more likely than men to have no regular partner because they are widowed, separated, or divorced.

Vaginal coitus was reported by nearly all females and males by the age of 25. Fifty-six per cent of males and 57 per cent of females reported vaginal coitus in the previous week, and non-penetrative sex was practiced by 75 per cent men and 82 per cent of women. Twenty-five per cent of males had genital stimulation in the previous 7 days. Cunnilingus and fellatio were common but less practiced than vaginal coitus. Of men and women aged 18 to 44, 60 per cent had oral sex in the previous year but in the 45- to 59-year-old group this fell to 30 per cent for women and 42 per cent for men. This and other sex surveys suggest that the practice of oral sex has increased since the 1950s and 1960s. Anal coitus was infrequent; approximately 14 per cent of the males and 13 per cent of the females had ever undertaken it, and only 7 per cent of males or females had practiced it in the previous year.

Modelling normal sexual function—(ii) the sexual response cycle

A direct way of investigating normal sexual function is to observe and measure the body changes that take place when men and women become sexually aroused. From these data, models have been constructed of the normal sequence of changes during sexual arousal, coitus, and orgasm. The first models described a simple sequence of increasing arousal and excitement culminating in rapid discharge by orgasm, displayed graphically as an ascent, peak, and then descent. As the investigations became more sophisticated, understanding of the body responses grew and the models became more detailed and complex.(5,15,16)

The EPOR model—a sexual response cycle model

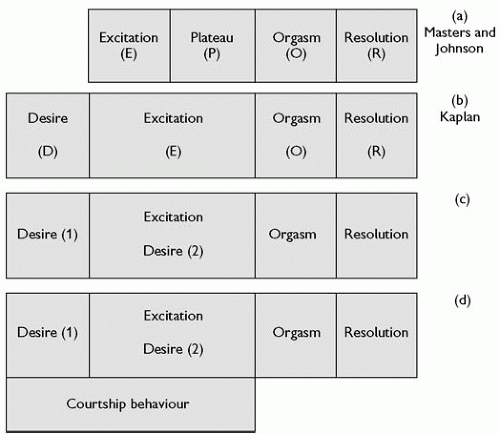

A most successful human sexual response model was that formulated by Masters and Johnson.(15) In the laboratory, they observed the changes that took place in the male and female body and especially the genitals during sexual arousal to orgasm either by masturbation or by natural or artificial coitus with a plastic penis that allowed internal filming of the female genitalia. After studying approximately 7500 female and 2500 male arousals to orgasm in some 382 female and 312 male volunteers over 11 years, they proposed a four-phase, sequential, and incremental model of the human sexual response cycle (Fig. 4.11.1.1). The phases were described as the excitation (E) phase (stimuli from somatogenic or psychogenic sources raise sexual tensions), the plateau (P) phase (sexual tensions intensified), the orgasmic (O) phase (involuntary pleasurable climax), and finally the resolution (R) phase (dissipation of sexual tensions). The great success of this EPOR model was its wide compass; it could characterize the sexual responses of women and men, both heterosexual and homosexual, ranging from simple petting to vaginal or anal coitus with or without orgasm. However, it had several weaknesses.

Fig. 4.11.1.1 The development of the human sexual response model from (a) the original EPOR model of Masters and Johnson(15) through (b) the desire, excitation, orgasmic, and resolution (DEOR) model of Kaplan(17) to (c) the proposed modification with desire phase 1 (before initiation of the excitation phase and desire phase 2 during excitation phase) and finally (d) with added courtship behaviour. |

Modifying the EPOR model into the DEOR model

The first weakness of the EPOR model is that it was derived from the study of a highly selected group of American men and women volunteers who could arouse themselves to orgasm in a laboratory, on demand, and allow themselves to be watched/filmed or measured for scientific and altruistic (or perhaps exhibitionistic) purposes. The second weakness was the lack of interobserver agreement about the changes observed and of confirmation of their sequential reliability. Robinson(16) examined the E phase and P phase, and concluded convincingly that the P phase was simply the final stage of the E phase. Helen Kaplan,(17) a New York sex therapist, proposed that before the E phase there should be a ‘desire phase’ (D phase). This proposal came from her work with women who professed to have no desire to be sexually aroused, even by their usual partners. She suggested that the desire must occur before sexual arousal can begin. Kaplan’s subjects were attending a clinic and remarkably no studies were ever conducted with a control normal population (either women or men) to investigate whether this ‘self-evident’ fact was true. Despite this, the EPOR model gradually became replaced by the desire, excitation, orgasmic, and resolution phase (DEOR) modification. While this is the currently accepted model, the centrality of the desire phase in women remains uncertain (Fig. 4.11.1.1). In a survey of non-clinic sexually experienced women in Denmark, about a third reported that they never experienced spontaneous sexual desire(18) and in an American survey women reported periods of several months when they lacked interest in sex.(13) The other problem with the desire phase is its location in the sequential DEOR model.

Sexual desire (D1-proceptive desire) that appears to be spontaneous (but presumably must still be activated by a trigger) should obviously be placed at the beginning of the model (Fig. 4.11.1.1b), while sexual desire (D2-receptive desire) created when the person is sexually aroused by another occurs during the E-phase (Fig. 4.11.1.1c).

Sexual desire (D1-proceptive desire) that appears to be spontaneous (but presumably must still be activated by a trigger) should obviously be placed at the beginning of the model (Fig. 4.11.1.1b), while sexual desire (D2-receptive desire) created when the person is sexually aroused by another occurs during the E-phase (Fig. 4.11.1.1c).

It has been proposed(19) that while the DEOR model fits for females in younger couples’ relationships for longer maintained ones sexual activity is undertaken often for factors such as intimacy, security, and acceptance and becomes more influenced by cognitive and emotional processes and the possible outcomes of the experience (e.g. mutual pleasure, confirming commitment and trust, enhancing emotional intimacy) rather than proceptive/ receptive desires.

Courtship (mating) behaviour—activity initiating normal sexual behaviour

With the possible exception of rape, the pre-initiation of sexual activity normally starts with flirting/courtship behaviours. Sometimes this activity can precede the desire phases; sometimes it occurs during the desire phases, and sometimes in the excitation phase (Fig. 4.11.1.1d).

Evolutionary psychology attempts to explain the strategies of mating.(20) Its message is not always palatable to modern sensitivities about sexual equality. It is argued that women invest more in their offspring than men,(21) that this investment is a scarce resource that men compete for, and that men can enhance their reproductive strategy by mating frequently. Most men are first visually attracted to a possible female sexual partner. They look for youthfulness and physical attractiveness in the form of regular features (symmetry), smooth complexion, optimum stature, and good physique, and they value virginity and chastity. Partner variety is highly desired. Women, however, need to obtain high-quality mates with abundant resources and look for emotional and financial status and security. Clearly the strategies conflict giving rise to different preferences in mate choice and casual sex, and different levels of investment or commitment to relationships.(22)

Once the chosen female (or male) accepts the initiation of flirting/ courtship behaviour, the subsequent stages form a stereotyped sequence which is found in many different cultures. The stages are look, approach, talk, touch, synchronize, kiss (caress), sex play, coitus. It is a sequence that the poet Ovid knew in the first century BCE. Morris(1) characterized human courtship behaviour further into 12 basic stages: eye to body, eye to eye, voice to voice, hand to hand, arm to shoulder, arm to waist, mouth to mouth, hand to head, hand to body, mouth to breast, hand to genitals, genitals to genitals. Similar hierarchies have been constructed extending the behaviour to oral-genital contacts.

Although kissing has been described as ‘an inhibited rehearsal for intercourse and other sexual practices’(23) and is usually undertaken in the courtship behaviour well before genital activity occurs, it is sometimes thought of as more intimate than coitus. Prostitutes, for example, traditionally do not kiss their clients on the mouth, reserving the activity for their private sexual behaviour. Nicholson(24) has speculated that kissing may be a mechanism by which semiochemicals (similar to pheromones) are exchanged between humans to induce bonding.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree