- Sleep almost certainly serves a vital function at the cellular level and is an absolute requirement for every animal

- In large population studies across the globe, chronically poor or insufficient sleep appears to correlate with increased mortality, arterial disease, diabetes and possibly cancer rates

- Sleep is highly orchestrated into discrete cycles of non-rapid eye movement (non-REM) and rapid eye movement (REM) stages

- Vivid dreams most often occur from the REM sleep stage

- Increasing age dramatically alters sleep quality and consolidation

- If insufficient deep non-REM sleep is obtained during a night, subjects will generally awake unrefreshed

- REM sleep is a very active brain state which has been proposed to facilitate memory consolidation and emotional processing although its true function ultimately remains obscure

- At least 90% of the adult population benefit from 7–8 hours of good sleep per night

- Around 5% of the population can be considered excessively sleepy during the day although increased sleepiness may not be recognised as such and may be expressed through other symptoms

- During nocturnal sleep, a variety of bodily movements is experienced normally

The importance of sleep

Virtually everyone acknowledges that significantly disturbed sleep has profound and immediate adverse effects on mental, cognitive and even physical well-being. However, the true long-term importance of good sleep for optimal general health may not yet be fully recognised.

The fact that every animal has evolved to have an absolute need for regular sleep in order to survive clearly suggests that it performs some vital and, as yet, ill-defined function. Intuitively, sleep appears to facilitate restoration and repair. Almost certainly, however, it has much more than a simple passive or restful role. In many respects, sleep is an active brain state and is not merely the absence of wakefulness. Indeed, during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, the brain is as metabolically active as during wakefulness. As a consequence, some authorities have termed REM sleep as ‘paradoxical sleep’.

In recent animal models, it appears that being awake for just a few hours vigorously activates metabolic ‘cell stress’ or adaptive biochemical pathways. This response to prolonged wakefulness is seen particularly in nerve cells that appear to be protecting themselves from damage and potential early death or apoptosis. It is therefore conceivable that any excess of wakefulness is the potentially damaging factor rather than a lack of sleep per se.

It is clearly difficult to study the long-term consequences of bad sleep in humans. Of interest, however, a large prospective four-year study of healthy elderly subjects suggested that the only reliable predictor of death or subsequent dependency from a large number of demographic details was a complaint of disordered sleep, particularly in males.

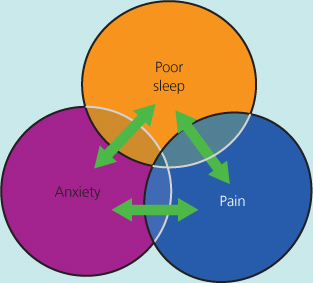

A renowned sleep researcher (William Dement) famously stated that ‘Sleep is of the brain, for the brain and by the brain’, emphasising the adverse effects of poor sleep predominantly on brain function and mental health. Conversely, virtually every central nervous system and mental health disorder has the potential to disturb the sleep–wake cycle. Furthermore, chronic poor quality or insufficient sleep may actively fuel many common conditions, such as generalised pain syndromes and affective disorders. This strongly suggests that sleep has a ‘bi-directional’ relationship with many common conditions (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Chronically poor quality or insufficient sleep is rarely an isolated problem. For example, pain and anxiety may well impede good sleep but sleep restriction or impairment can also increase sensitivity to pain and raise anxiety levels.

In many situations, it is possible that direct attention both to sleep quantity and quality may have indirect and positive effects on an unexpected range of health issues. In this respect, the established epidemiological links between chronic sleep deprivation (less than six hours a night) and diabetes, hypertension, vascular disease or even cancer are increasingly germane. The difficult and important question of whether increasing quantity or quality of sleep in ‘at risk’ populations will positively affect outcome remains to be established.

Defining sleep

The loose behavioural definition of sleep as a temporary and reversible state of altered consciousness and perceptual disengagement has been superseded by electrophysiological criteria.

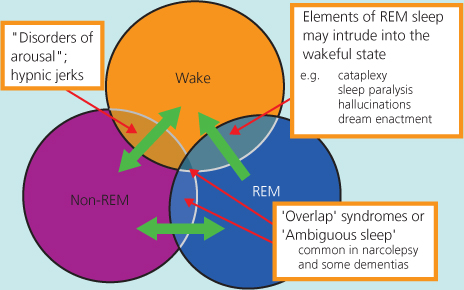

Although simplistic, it is valid to consider three distinct and mutually exclusive brain states, namely wakefulness, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and non-REM sleep (Figure 1.2). Switches between these states should occur automatically, quickly and relatively seamlessly. A large proportion of sleep disorders is associated with inefficient, faulty or incomplete states of transition.

Figure 1.2 The brain can be considered as normally existing in the three mutually exclusive states of WAKE, non-REM or REM sleep. Orchestrated transitions between these states occur automatically and relatively quickly over the 24-hour period. In many sleep disorders, particularly the parasomnias, the switch between states may be inefficient or incomplete.

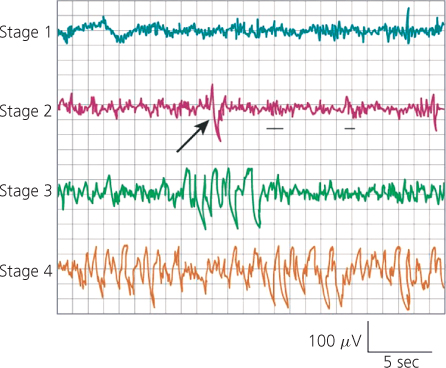

Non-REM sleep can be divided into light (stages 1 and 2) or deep phases (stages 3 and 4) on the basis of the surface cerebral electroencephalogram (EEG) (Figure 1.3). Around 20% of the night is spent in the curious state of REM sleep, in which most of the cerebral cortex and limbic system is extremely active, as confirmed by recent functional brain imaging studies. In contrast to this enhanced metabolic activity, there are descending inhibitory neural impulses from the brainstem that innervate the vast majority of peripheral muscles during REM sleep, rendering the subject floppy (atonic) and areflexic.

Figure 1.3 Representative electroencephalographic (EEG) traces of the 4 stages of non-REM sleep. The arrow indicates a K-complex, one of the hallmarks of light non-REM sleep. Large amplitude delta (slow) waves dominate the trace in deep non-REM sleep (stages 3 and 4).

In recently revised criteria for sleep staging, light non-REM sleep (stages 1 and 2) has been designated as N1 whereas deep non-REM (stages 3 and 4) is N2. This revision has not been completely accepted internationally at the time of writing.

REM sleep loosely correlates with the normal phenomena of dreams or nightmares, usually recalled briefly if a subject is awoken from this stage of sleep. However, less vivid or bizarre ‘sleep mentation’, usually without a narrative thread, is also frequently reported if arousals from sleep occur from non-REM sleep stages.

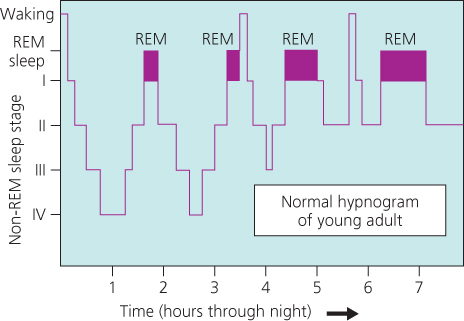

An ideal nocturnal sleep in young adults consists of four or five cycles of REM/non-REM sleep with deep non-REM sleep dominating the first third of the night and REM sleep the last third (Figure 1.4). Minor arousals from sleep are common, especially with increasing age, and often not registered or recalled.

Figure 1.4 A typical hypnogram of a young adult showing discrete cycles of non-REM and REM sleep through the night. Deep non-REM sleep predominates in the first third whereas REM sleep is most dense in the last third. Brief awakenings are often not recognised. If they occur during REM sleep, a vivid dream would be expected.

How much sleep is needed?

There is clearly a degree of individual variation in the optimum length of the nocturnal sleep period but probably 90% of adults require at least seven hours of good quality sleep. For most people, sleeping regularly for six hours or less produces objective signs of reduced vigilance, even if subjective sleepiness is minimal.

Although sleepiness is the obvious consequence of acute sleep deprivation, increasingly, a number of studies have demonstrated neuropsychological effects (Table 1.1). The majority of these can be interpreted in terms of temporary frontal lobe dysfunction. Many have commented that the sleep-deprived brain of a young adult functions in a similar way to the brain in extreme old age.

Table 1.1 A selected list of the neuropsychological effects secondary to acute sleep deprivation.

| Main neuropsychological effect of acute | Year of study |

| sleep deprivation | |

| Increased reaction times | 1988 |

| Perseveration and reduced flexibility | 1999 |

| Impaired sense of humour | 2006 |

| Increased risk taking | 2007 |

| Impaired moral judgement | 2007 |

| Reduced emotional intelligence | 2010 |

| Increased ‘negativity’ with enhanced memory for adverse events | 2010 |

| Increased distractibility | 2010 |

Although underlying mechanisms are unclear and precise interpretation is difficult, several enormous population studies have consistently reported increased mortality, vascular disease and diabetes in those reporting less than five hours of sleep per night when followed up for several years. Intriguingly, those sleeping for more than 9.5 hours a night similarly have reduced longevity.

Increasingly, it is realised that the nature of sleep may be as crucially important as its quantity, although precise definitions of sleep quality are poorly defined. The absolute amount of deep non-REM (slow wave) sleep through the night may predict how refreshed a subject feels in the morning but other measures, such as the time spent awake after sleep onset, may also be used as surrogate markers of quality.

The true function of REM sleep remains a mystery. Most awakenings from REM sleep are associated with vivid dreams that often have a bizarre narrative, incorporating elements of recent events or more distant memories. Psychoanalytic explanations of dreams in terms of ‘wish fulfilment’ have largely been superseded by more biological explanations. However, it remains unclear whether it is the dream itself or the underlying neurobiological processes behind REM sleep that are more important.

A common thread with much recent research on REM sleep function concerns memory processing or consolidation. In brief, one influential view is that the brain restructures or consolidates certain forms of memory through a form of rehearsal when ‘off-line’ during REM sleep. It is likely that processing of emotional memories is a particularly important function. Many cognitive tasks seem to improve after a period of sleep and some evidence even supports the notion that unexpected insights into mathematical problems occur during the unconscious state of sleep.

The study of dreams, oneirology, has a rich history. Many theories regarding dream function and REM sleep have been generated. Some interesting facts concerning REM sleep are listed in Box 1.1.