OBJECTIVES

Define obesity.

Describe the populations most affected by obesity.

Describe the health consequences of obesity.

Discuss the difficulties with losing weight, including patient and health-care provider challenges.

Suggest ways for health-care providers to discuss weight loss with patients.

Describe strategies for weight loss.

Esmeralda, a 15-year-old girl, requests a written excuse to skip school physical education classes. Her body mass index (BMI) of 32 reveals that she is in the highest weight category for girls her age. She often skips breakfast and eats most meals in front of the television. Her family members are also obese and have type II diabetes.

Worldwide young and old are being affected by obesity and its complications. Indeed, the obesity “epidemic” may be one of the most significant challenges to global, as well as national health. Paradoxically, poor families are particularly affected because of coexisting undernutrition, lack of resources to eat healthily, and inadequate venues for exercise.

Tackling the obesity epidemic will be not an easy feat because its causes are complex–bridging societal issues (such as governmental subsidies of high caloric food), and personal ones (how active people are). Although health-care providers need to be engaged in the wider public health and community efforts addressing obesity, helping patients as they strive to lose weight or suffer from its consequences remains equally important. This chapter discusses both the challenges and strategies of addressing obesity.

DEFINITIONS OF OBESITY

The most widely used classification system for obesity–an abnormal accumulation of body fat–in adults is the body mass index (BMI). The BMI estimates the amount of body fat through a calculation that adjusts weight for height (see “Resources” for online BMI calculator). A normal adult BMI is between 18.5 and 24.9. BMIs between 25 and 29.9 indicate overweight, a BMI greater than 30 indicates obesity, and a BMI greater than 40 indicates extreme obesity. Although health implications of BMI cutoffs vary across ethnic groups,1 it is accepted that increasing BMI is associated with an increased risk of death from cancers and cardiovascular disease. Obesity was most strongly associated with an increased risk of death among never smokers who had no history of disease.2,3

BMI for children, unlike adults, is both age and gender specific because children’s bodies change dramatically as they grow, and these changes differ between boys and girls. Terminology for classifying BMI in children has changed and now the language is more consistent with the adult classification (Box 37-1).4 Because in older adolescents a BMI of 95th percentile is higher than the adult cut point of 30 kg/m2, obesity in this population is defined as BMI > 95 percentile or BMI > 30 kg/m2, whichever is lower.4

Box 37-1. Classification System for Obesity

| Classification | Body Mass Index for Adults | Body Mass Index for Children |

|---|---|---|

| Underweight | <18.5 | <5th percentile |

| Healthy weight | 18.5–24.9 | 5th percentile to <85th percentile |

| Overweight | 25–29.9 | 85th percentile to <95th percentile |

| Obesity | >30 | >95th percentile |

In adults, the waist circumference–the body circumference measured at the level of the superior iliac crest–is another measurement that, some argue, better explains obesity-related health risk. Increased waist circumference, a measure of central adiposity, has been shown to be a marker for increased risk even in persons of normal weight. A waist circumference greater than 40 inches in men, and 35 inches in women is considered abnormal and increases the risk of developing hypertension, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome.5

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF OBESITY

Between 1980 and 2013, the prevalence of overweight and obese people worldwide rose by 27.5% in adults and 47.1% in children. Sixty-two percent of the world’s obese people live in developing countries. In 2013, the United States had the highest proportion of obese people, 13% of the world’s total.6

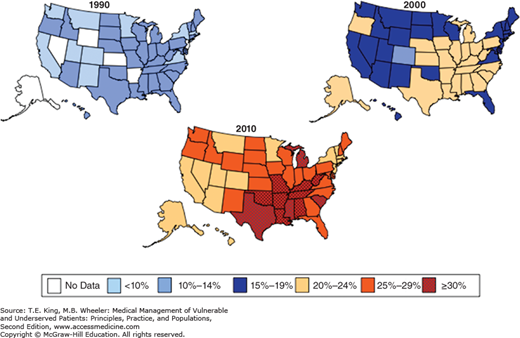

The number of overweight and obese people in the United States has significantly increased in recent decades (Figure 37-1). In 2011 to 2012, 68.5% of adults were either overweight or obese. Of these, 34.9% of adults were obese and 6.4% had grade 3 obesity with a BMI ≥40.7 Approximately 17% of children and adolescents aged 2–19 years are obese. In general, the highest rates of obesity are found in Latinos and African Americans as well as in populations (particularly females) with less education and lower incomes.7,8

Figure 37-1.

Obesity trends among US adults: 1990, 2000, 2010. Data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (1990, 2000, 2010) for BMI ≥ 30, or about 30 lb overweight for 5’4” person. (Source: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, CDC. Accessed July 6, 2014. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/downloads/obesity_trends_2010.ppt.)

Unfortunately, obesity prevalence rates have not substantially decreased in the past decade. The prevalence of obesity in women 60 years or older has actually increased.7 An exception to this has been seen in young children with a decrease in obesity and extreme obesity in low-income children aged 2–4 from 2003 to 2010.9 These declines were seen in all ethnic groups except American Indians/Alaska Natives. An overall decline is further supported by data showing a 40% decrease in obesity in children aged 2–5 from 2003–2004 to 2011–2012.7 Reasons for these declines are unclear, but possibilities include increased breastfeeding and decreased consumption of sugary beverages. It is also unclear if this finding will persist with aging.

The economic impact of obesity is substantial. Direct medical spending for diagnosis and treatment has been estimated at up to $147 billion a year in the United States.10 This does not include the indirect costs of income lost from decreased productivity, disability, absenteeism, and premature mortality, which when totaled are in excess of $200 billion annually.10,11

HEALTH CONSEQUENCES OF OBESITY

The health consequences of obesity for both adults and children are significant (Table 37-1). Complications such as hypertension, diabetes, elevated cholesterol levels, and sleep apnea increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, which remains the leading cause of death in both men and women. Not surprisingly, those with the highest rates of obesity suffer from the highest rates of these cardiovascular diseases as well.12 The same trend even extends to children. For example, nearly half of the newly diagnosed diabetes cases in pediatric populations are type 2 diabetes. This increase is attributable to increasing rates of obesity in children and is highest in African Americans, Mexican Americans, and Native Americans.13 Other complications of obesity, such as osteoarthritis or depression, may not be as life threatening, but may cause significant incapacity. Arthritis is the most common cause of disability in the United States.

| Organ System | Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular |

|

| Dermatologic |

|

| Endocrine |

|

| Gastrointestinal |

|

| Musculoskeletal |

|

| Oncologic | Variety of cancers |

| Pulmonary |

|

| Psychological |

|

Some of the health consequences of obesity can be mitigated by physical fitness. Those who are obese but physically fit have better mortality rates than their sedentary counterparts. However, both groups have mortality rates greater than individuals who are physically fit and not obese.14,15 Therefore, patients and health-care providers should note that although physical activity is beneficial, it is not a substitute for weight loss.

LOSING WEIGHT IS HARD TO DO

Esmeralda’s mother works two sedentary jobs. She has failed at multiple attempts to lose weight. The family eats cheap, fatty, high-calorie food. No one in the family feels they have the money, time, or energy to exercise.

The battle to lose weight is often thwarted by lack of time to prepare food at home and the resources to make healthy choices. Eating out at restaurants and eating prepared foods have become common and perhaps necessary as women exchanged housework for paid labor. According to the Department of Labor, among families with children, 59% of these families have dual-income parents; and among single-women head of households, the mothers are employed in 67% of these households.16 The National Restaurant Association reported that the total restaurant industry sales increased from $42.8 billion in 1970 to $586.7 billion in 2010. In 1950, 25% of all food spending was on food away from home, by 2014, this share rose to 47% of household food budget.17

Both larger portion sizes and poorer nutritional quality of food prepared or consumed outside the home encourage greater calorie and fat consumption than home-cooked foods. Portion sizes have been increasing in both prepackaged, ready-to-eat products and at restaurants. Overconsumption is fueled by these larger sizes marketed as providing more for your money.

In addition, increasing evidence suggests an important role for the microbiome in the metabolism of energy and has led to alternative theories regarding the role of the changing gut microbiome in the global obesity epidemic.18

Food insecurity, not having regular access to quality foods or having interruptions in eating patterns or unplanned reduction in food intake, is also linked to obesity.19,20 Families that are food insecure are more likely to skip meals or eat unbalanced meals which hampers healthy weight management.

Food prices influence food consumption. In the United States, income is associated with the type of food consumed, not necessarily the quantity.21 Calorie-dense foods such as sodas, fruit drinks, and snack foods are inexpensive. Government subsidies favoring corn syrup and sugar production underlie some of these price differences. Healthier foods, such as fruits and vegetables, are sold more frequently in grocery stores, which often are lacking in low-income neighborhoods.22 Higher cost, limited cooking facilities, perceived ability to satisfy hunger, and short shelf-life of fresh foods can discourage purchase of fruits and vegetables in low socioeconomic groups.23,24

Lack of physical activity hampers efforts at weight control and health maintenance. Long work hours, multiple shifts, increasing time devoted to sedentary behaviors such as television viewing and other media (videos and computers) have been cited as important contributors to the decline in physical activity. Less than one-third of young people meet national recommendations of engaging in physical activity at least 60 minutes each day. Rates are worse among ethnic minority groups, specifically Blacks and Hispanics.25 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), fewer than half (48%) of US adults meet the current physical activity recommendations of 150 minutes of moderate physical activity each week. Again, rates are lower in Black and Hispanic populations as well as in groups of lower socioeconomic status and educational attainment.26

Watching television is problematic not only because it is a sedentary activity but also television and radio advertisements highlight quick and easy access to food that is already prepared and of low nutritional value.27 Children in particular are targeted for advertising–even in schools. Some school districts, in search of extra revenue, have contracted with soft drink companies who provide service vending machines throughout the school district. Some schools have eliminated recess and physical education, decreasing children’s daily physical activity. Adults do not fare much better, as long workdays and increasing family demands serve as barriers to regular exercise.

Low-income urban neighborhoods impose other impediments to healthy lifestyles as well. The dearth of grocery stores (food deserts) offering fresh produce and lean meat and plethora of fast food restaurants and convenience stores (food swamps) encourage high-fat, low-fiber diets. Ability to exercise may be compromised by insufficient playgrounds, and parks and trails for walking or biking. Existing areas may not be perceived to be safe. Major fitness centers rarely open exercise facilities in low-income areas, and their membership costs are expensive in most cases.

Patients’ motivation to lose weight is also influenced by cultural norms and expectations. Many studies have demonstrated that African Americans and some Latinos are more accepting of a larger body size than whites and Asian Americans.28,29,30,31,32,33,34 Consequently, some obese women may not recognize themselves as having a weight problem35–this misperception in turn decreases their awareness of disease risk. Additionally, tolerance of larger adult sizes may have an impact on parental recognition of excess weight in children. A meta-analysis of parental estimation of weight status in children demonstrated that 51% of parents underestimate their overweight or obese children’s weight. This underestimation is strongly influenced by parental weight status.36

The impact of body-shape perceptions is also evident in minority women during childbearing years. It is widely accepted that gestational weight gain affects postpartum weight retention and risk for obesity. Certain demographic groups are at greater risk for excessive gestational weight gain. These include women of low socioeconomic strata, low educational attainment, and African-American ethnicity.37 In a focus group study by Groth et al,37 low-income African-American women were accepting of excessive gestational weight gain and associated it with having a healthy infant.

The role of food in many cultures also can have an enormous impact on diet, and subsequently weight control. In focus groups with mothers from low-socioeconomic strata, they admitted to using sweets to bribe their children or reward good behavior and to encouraging them to eat more even when they were full.38 The use of food as reward, bribe, or pacifier and the notion of “cleaning the plate” are issues that need to be addressed in discussions of diet because they relate to healthful eating within families.

Interventions designed to help vulnerable populations with weight control will need to consider and address cultural norms and practices related to weight and body size. Focus on “healthy eating” and “active living” instead of obesity and weight loss may be more effective approaches for educating and engaging culturally diverse groups.

Research of obese people’s experiences suggests that their weight has contributed to negative treatment by strangers and friends, at job interviews, in the work place, in social settings, at exercise facilities, and by health-care providers.39,40,41 Many of the same groups that suffer discrimination based on race, socioeconomic status, and education are more likely to be obese, and consequently suffer an inordinate amount of prejudice.

It is important to acknowledge that subtle forms of discrimination exist in the health-care setting (scales that do not weigh individuals over 300 pounds, chairs with arm rests that are too narrow for obese patients, blood pressure cuffs that are too small for proper measurements). In addition, health-care providers often are guilty of blaming the obese patient for their weight problems and rarely consider the environmental, economic, and social influences on the weight of their patients.42 Obese patients may feel that health-care providers are not genuinely concerned about them or their health when simple courtesies are neglected. The feeling of second-class treatment or being blamed for a medical problem can negatively affect a person’s interest in discussing weight loss with a provider. Recognizing and discussing an obese patient’s discomfort in the medical setting can open lines of communication and foster trust relating to all health issues, including weight.

Once considered a problem of wealthy nations, obesity rates are on the rise in low- and middle-income countries, particularly in urban areas. More than 50% of the 671 million obese individuals in the world live in 10 countries: the United States, China, India, Russia, Brazil, Mexico, Egypt, Germany, Pakistan, and Indonesia.6

The worldwide causes of obesity are similar to those in the United States–an increase in calorie-dense food and decrease in physical activity. Rising incomes in some countries have increased access to high-fat calorically dense foods. Additional factors related to urbanization, globalization, and modernization such as increased television viewing, eating outside of the home, and shifts in agricultural work to service and manufacturing industries have contributed as well. The health consequences of obesity are similar to those seen in the US populations, but many countries are doubly challenged combating complications of obesity as well as those of infectious disease and malnutrition. With increases in obesity driving concomitant increases in diabetes, certain infectious risks, such as those for tuberculosis, may also increase. Unfortunately, the resultant economic burden often falls on countries ill prepared to deal with it.

HEALTH-CARE PROVIDER CHALLENGES

Obesity is a preventable disease and often is described as the second leading cause of preventable death (tobacco use is the first) in the United States. However, in addition to difficulties faced by patients, providers have their own struggles in assisting patients with weight loss (Box 37-2).

Box 37-2. Common Pitfalls to Obesity Management

Not regularly identifying obesity as a health problem

Neglecting patient time and cost concerns in counseling efforts

Not addressing need for family involvement in weight loss efforts

Not recognizing environmental barriers to healthy lifestyles

Not incorporating cultural expectations of ideal weight into weight loss goals

Allowing the health consequences of obesity to overwhelm clinical encounters, leaving little time for weight reduction counseling

Lacking the skills to counsel patients on weight loss