Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders

10.1 Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

10.1 Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is represented by a diverse group of symptoms that include intrusive thoughts, rituals, preoccupations, and compulsions. These recurrent obsessions or compulsions cause severe distress to the person. The obsessions or compulsions are time-consuming and interfere significantly with the person’s normal routine, occupational functioning, usual social activities, or relationships. A patient with OCD may have an obsession, a compulsion, or both.

An obsession is a recurrent and intrusive thought, feeling, idea, or sensation. In contrast to an obsession, which is a mental event, a compulsion is a behavior. Specifically, a compulsion is a conscious, standardized, recurrent behavior, such as counting, checking, or avoiding. A patient with OCD realizes the irrationality of the obsession and experiences both the obsession and the compulsion as ego-dystonic (i.e., unwanted behavior).

Although the compulsive act may be carried out in an attempt to reduce the anxiety associated with the obsession, it does not always succeed in doing so. The completion of the compulsive act may not affect the anxiety, and it may even increase the anxiety. Anxiety is also increased when a person resists carrying out a compulsion. A variety of OCD conditions are described in this section and those that follow (Sections 10.2–10.5).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The rates of OCD are fairly consistent, with a lifetime prevalence in the general population estimated at 2 to 3 percent. Some researchers have estimated that the disorder is found in as many as 10 percent of outpatients in psychiatric clinics. These figures make OCD the fourth most common psychiatric diagnosis after phobias, substance-related disorders, and major depressive disorder. Epidemiological studies in Europe, Asia, and Africa have confirmed these rates across cultural boundaries.

Among adults, men and women are equally likely to be affected, but among adolescents, boys are more commonly affected than girls. The mean age of onset is about 20 years, although men have a slightly earlier age of onset (mean about 19 years) than women (mean about 22 years). Overall, the symptoms of about two thirds of affected persons have an onset before age 25, and the symptoms of fewer than 15 percent have an onset after age 35. The onset of the disorder can occur in adolescence or childhood, in some cases as early as 2 years of age. Single persons are more frequently affected with OCD than are married persons, although this finding probably reflects the difficulty that persons with the disorder have maintaining a relationship. OCD occurs less often among blacks than among whites, although access to health care rather than differences in prevalence may explain the variation.

COMORBIDITY

Persons with OCD are commonly affected by other mental disorders. The lifetime prevalence for major depressive disorder in persons with OCD is about 67 percent and for social phobia about 25 percent. Other common comorbid psychiatric diagnoses in patients with OCD include alcohol use disorders, generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobia, panic disorder, eating disorders, and personality disorders. OCD exhibits a superficial resemblance to obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, which is associated with an obsessive concern for details, perfectionism, and other similar personality traits. The incidence of Tourette’s disorder in patients with OCD is 5 to 7 percent, and 20 to 30 percent of patients with OCD have a history of tics.

ETIOLOGY

Biological Factors

Neurotransmitters

SEROTONERGIC SYSTEM. The many clinical drug trials that have been conducted support the hypothesis that dysregulation of serotonin is involved in the symptom formation of obsessions and compulsions in the disorder. Data show that serotonergic drugs are more effective in treating OCD than drugs that affect other neurotransmitter systems, but whether serotonin is involved in the cause of OCD is not clear. Clinical studies have assayed cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations of serotonin metabolites (e.g., 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid [5-HIAA]) and affinities and numbers of platelet-binding sites of tritiated imipramine (Tofranil), which binds to serotonin reuptake sites, and have reported variable findings of these measures in patients with OCD. In one study, the CSF concentration of 5-HIAA decreased after treatment with clomipramine (Anafranil), focusing attention on the serotonergic system.

NORADRENERGIC SYSTEM. Currently, less evidence exists for dysfunction in the noradrenergic system in OCD. Anecdotal reports show some improvement in OCD symptoms with use of oral clonidine (Catapres), a drug that lowers the amount of norepinephrine released from the presynaptic nerve terminals.

NEUROIMMUNOLOGY. Some interest exists in a positive link between streptococcal infection and OCD. Group Aβ-hemolytic streptococcal infection can cause rheumatic fever, and approximately 10 to 30 percent of the patients develop Sydenham’s chorea and show obsessive-compulsive symptoms.

Brain-Imaging Studies. Neuroimaging in patients with OCD has produced converging data implicating altered function in the neurocircuitry between orbitofrontal cortex, caudate, and thalamus. Various functional brain-imaging studies—for example, positron emission tomography (PET)—have shown increased activity (e.g., metabolism and blood flow) in the frontal lobes, the basal ganglia (especially the caudate), and the cingulum of patients with OCD. The involvement of these areas in the pathology of OCD appears more associated with corticostriatal pathways than with the amygdala pathways, which are the current focus of much anxiety disorder research. Pharmacological and behavioral treatments reportedly reverse these abnormalities (Fig. 10.1-1). Data from functional brain-imaging studies are consistent with data from structural brain-imaging studies. Both computed tomographic (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have found bilaterally smaller caudates in patients with OCD. Both functional and structural brain-imaging study results are also compatible with the observation that neurological procedures involving the cingulum are sometimes effective in the treatment of OCD. One recent MRI study reported increased T1 relaxation times in the frontal cortex, a finding consistent with the location of abnormalities discovered in PET studies.

FIGURE 10.1-1

Brain regions implicated in the pathophysiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder. (From Rosenberg DR, MacMillan SN, Moore GJ. Brain anatomy and chemistry may predict treatment response in paediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. In J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001; 4:179, with permission.)

Genetics. Available genetic data on OCD support the hypothesis that the disorder has a significant genetic component. Relatives of probands with OCD consistently have a threefold to fivefold higher probability of having OCD or obsessive-compulsive features than families of control probands The data, however, do not yet distinguish the heritable factors from the influence of cultural and behavioral effects on the transmission of the disorder. Studies of concordance for the disorder in twins have consistently found a significantly higher concordance rate for monozygotic twins than for dizygotic twins. Some studies also demonstrate increased rates of a variety of conditions among relatives of OCD probands, including generalized anxiety disorder, tic disorders, body dysmorphic disorder, hypochondriasis, eating disorders, and habits such as nail-biting.

Other Biological Data. Electrophysiological studies, sleep electroencephalogram (EEG) studies, and neuroendocrine studies have contributed data that indicate some commonalities between depressive disorders and OCD. A higher than usual incidence of nonspecific EEG abnormalities occurs in patients with OCD. Sleep EEG studies have found abnormalities similar to those in depressive disorders, such as decreased rapid eye movement latency. Neuroendocrine studies have also produced some analogies to depressive disorders, such as nonsuppression on the dexamethasone-suppression test in about one-third of patients and decreased growth hormone secretion with clonidine infusions.

As mentioned, studies have suggested a possible link between a subset of OCD cases and certain types of motor tic syndromes (i.e., Tourette’s disorder and chronic motor tics). A higher rate of OCD, Tourette’s disorder, and chronic motor tics are found in relatives of patients with Tourette’s disorder than in relatives of controls, whether or not they had OCD. Most family studies of probands with OCD have found increased rates of Tourette’s disorder and chronic motor tics only among the relatives of probands with OCD who also have some form of tic disorder. Evidence also suggests cotransmission of Tourette’s disorder, OCD, and chronic motor tics within families.

Behavioral Factors

According to learning theorists, obsessions are conditioned stimuli. A relatively neutral stimulus becomes associated with fear or anxiety through a process of respondent conditioning by being paired with events that are noxious or anxiety producing. Thus, previously neutral objects and thoughts become conditioned stimuli capable of provoking anxiety or discomfort.

Compulsions are established in a different way. When a person discovers that a certain action reduces anxiety attached to an obsessional thought, he or she develops active avoidance strategies in the form of compulsions or ritualistic behaviors to control the anxiety. Gradually, because of their efficacy in reducing a painful secondary drive (anxiety), the avoidance strategies become fixed as learned patterns of compulsive behaviors. Learning theory provides useful concepts for explaining certain aspects of obsessive-compulsive phenomena—for example, the anxiety-provoking capacity of ideas not necessarily frightening in themselves and the establishment of compulsive patterns of behavior.

Psychosocial Factors

Personality Factors. OCD differs from obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, which is associated with an obsessive concern for details, perfectionism, and other similar personality traits. Most persons with OCD do not have premorbid compulsive symptoms, and such personality traits are neither necessary nor sufficient for the development of OCD. Only about 15 to 35 percent of patients with OCD have had premorbid obsessional traits.

Psychodynamic Factors. Psychodynamic insight may be of great help in understanding problems with treatment compliance, interpersonal difficulties, and personality problems accompanying the Axis I disorder. Many patients with OCD may refuse to cooperate with effective treatments such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and behavior therapy. Even though the symptoms of OCD may be biologically driven, psychodynamic meanings may be attached to them. Patients may become invested in maintaining the symptomatology because of secondary gains. For example, a male patient, whose mother stays home to take care of him, may unconsciously wish to hang on to his OCD symptoms because they keep the attention of his mother.

Another contribution of psychodynamic understanding involves the interpersonal dimensions. Studies have shown that relatives will accommodate the patient through active participation in rituals or significant modifications of their daily routines. This form of family accommodation is correlated with stress in the family, rejecting attitudes toward the patient, and poor family functioning. Often, the family members are involved in an effort to reduce the patient’s anxiety or to control the patient’s expressions of anger. This pattern of relatedness may become internalized and be re-created when the patient enters a treatment setting. By looking at recurring patterns of interpersonal relationships from a psychodynamic perspective, patients may learn how their illness affects others.

Finally, one other contribution of psychodynamic thinking is recognition of the precipitants that initiate or exacerbate symptoms. Often, interpersonal difficulties increase the patient’s anxiety and, thus, increase the patient’s symptomatology as well. Research suggests that OCD may be precipitated by a number of environmental stressors, especially those involving pregnancy, childbirth, or parental care of children. An understanding of the stressors may assist the clinician in an overall treatment plan that reduces the stressful events themselves or their meaning to the patient.

SIGMUND FREUD. In classic psychoanalytic theory, OCD was termed obsessive-compulsive neurosis and was considered a regression from the oedipal phase to the anal psychosexual phase of development. When patients with OCD feel threatened by anxiety about retaliation for unconscious impulses or by the loss of a significant object’s love, they retreat from the oedipal position and regress to an intensely ambivalent emotional stage associated with the anal phase. The ambivalence is connected to the unraveling of the smooth fusion between sexual and aggressive drives characteristic of the oedipal phase. The coexistence of hatred and love toward the same person leaves patients paralyzed with doubt and indecision.

An example of how Freud viewed OCD symptoms is described by Otto Fenichel in the case study presented here.

A patient, who was not analyzed, complained in the first interview that he suffered from the compulsion to look backward constantly, from fear that he might have overlooked something important behind him. These ideas were predominant; he might overlook a coin lying on the ground; he might have injured an insect by stepping on it; or an insect might have fallen on its back and need his help. The patient was also afraid of touching anything, and whenever he had touched an object he had to convince himself that he had not destroyed it. He had no vocation because the severe compulsions disturbed all his working activity; however, he had one passion: housecleaning. He liked to visit his neighbors and clean their houses, just for fun. Another symptom was described by the patient as his “clothes consciousness”; he was constantly preoccupied with the question whether or not his suit fitted. He, too, stated that sexuality did not play an important part in his life. He had sexual intercourse two or three times a year only, and exclusively with girls in whom he had no personal interest. Later on, he mentioned another symptom. As a child, he had felt his mother to be disgusting and had been terribly afraid of touching her. There was no real reason whatsoever for such a disgust, for the mother had been a nice person.

In the clinical picture for this case study, Freud believed the need to be clean and not to touch is related to anal sexuality, and the disgust for the mother is a reaction against incestuous fears.

One of the striking features of patients with OCD is the degree to which they are preoccupied with aggression or cleanliness, either overtly in the content of their symptoms or in the associations that lie behind them. The psychogenesis of OCD, therefore, may lie in disturbances in normal growth and development related to the anal-sadistic phase of development.

Ambivalence. Ambivalence is an important feature of normal children during the anal-sadistic developmental phase; children feel both love and murderous hate toward the same object, sometimes simultaneously. Patients with OCD often consciously experience both love and hate toward an object. This conflict of opposing emotions is evident in a patient’s doing and undoing patterns of behavior and in paralyzing doubt in the face of choices.

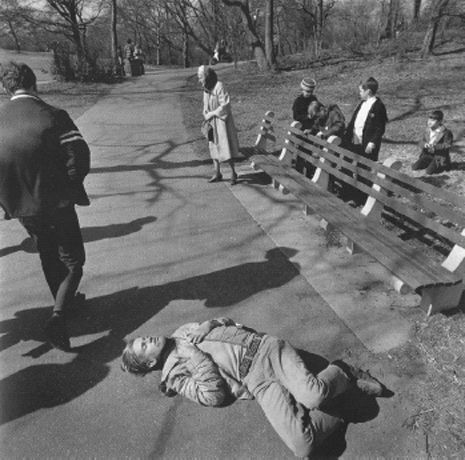

Magical Thinking. In magical thinking, regression uncovers early modes of thought rather than impulses; that is, ego functions as well as id functions are affected by regression. Inherent in magical thinking is omnipotence of thought. Persons believe that merely by thinking about an event in the external world they can cause the event to occur without intermediate physical actions. This feeling causes them to fear having an aggressive thought (Fig. 10.1-2).

FIGURE 10.1-2

In magical thinking, one believes that the thought is equal to the deed, that wishing a person dead will make it happen, as symbolized in this illustration. (Courtesy of Arthur Tress.)

DIAGNOSIS AND CLINICAL FEATURES

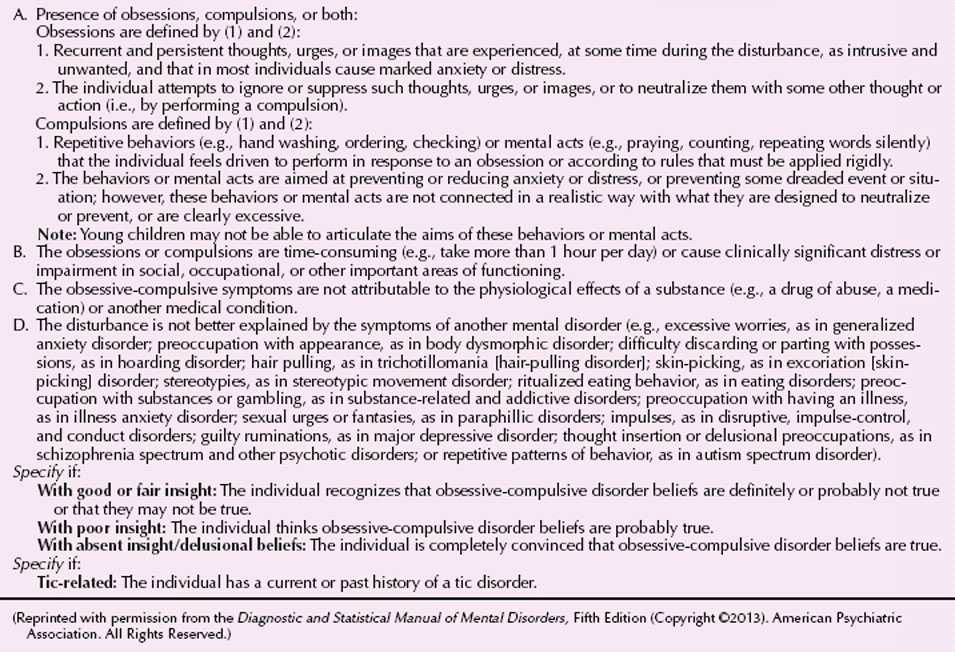

As part of the diagnostic criteria for OCD, the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) allows clinicians to indicate whether the patient’s OCD is characterized by good or fair insight, poor insight, or absent insight (Table 10.1-1). Patients with good or fair insight recognize that their OCD beliefs are definitely or probably not true or may or may not be true. Patients with poor insight believe their OCD beliefs are probably true, and patients with absent insight are convinced that their beliefs are true.

Table 10.1-1

Table 10.1-1

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

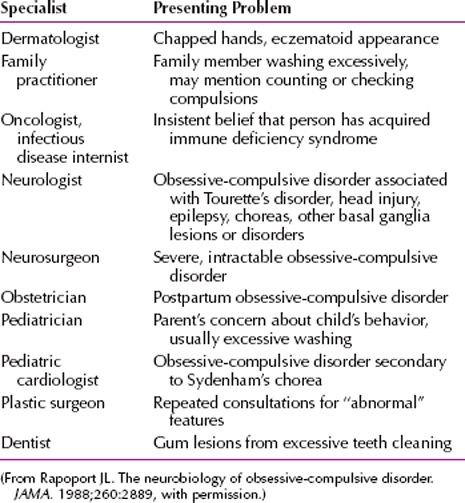

Patients with OCD often take their complaints to physicians rather than psychiatrists (Table 10.1-2). Most patients with OCD have both obsessions and compulsions—up to 75 percent in some surveys. Some researchers and clinicians believe that the number may be much closer to 100 percent if patients are carefully assessed for the presence of mental compulsions in addition to behavioral compulsions. For example, an obsession about hurting a child may be followed by a mental compulsion to repeat a specific prayer a specific number of times. Other researchers and clinicians, however, believe that some patients do have only obsessive thoughts without compulsions. Such patients are likely to have repetitious thoughts of a sexual or aggressive act that is reprehensible to them. For clarity, it is best to conceptualize obsessions as thoughts and compulsions as behavior.

Table 10.1-2

Table 10.1-2

Nonpsychiatric Clinical Specialists Likely to See Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Patients

Obsessions and compulsions are the essential features of OCD. An idea or an impulse intrudes itself insistently and persistently into a person’s conscious awareness. Typical obsessions associated with OCD include thoughts about contamination (“My hands are dirty”) or doubts (“I forgot to turn off the stove”).

A feeling of anxious dread accompanies the central manifestation, and the key characteristic of a compulsion is that it reduces the anxiety associated with the obsession. The obsession or the compulsion is ego-alien; that is, it is experienced as foreign to the person’s experience of himself or herself as a psychological being. No matter how vivid and compelling the obsession or compulsion, the person usually recognizes it as absurd and irrational. The person suffering from obsessions and compulsions usually feels a strong desire to resist them. Nevertheless, about half of all patients offer little resistance to compulsions, although about 80 percent of all patients believe that the compulsion is irrational. Sometimes, patients overvalue obsessions and compulsions—for example, they may insist that compulsive cleanliness is morally correct, even though they have lost their jobs because of time spent cleaning.

Symptom Patterns

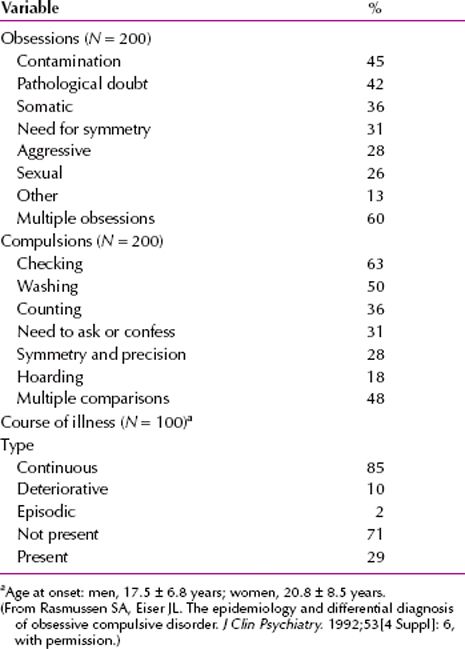

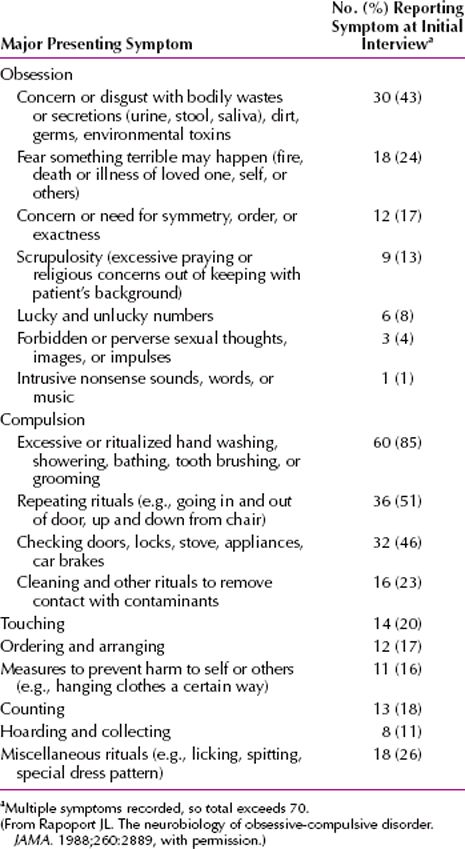

The presentation of obsessions and compulsions is heterogeneous in adults (Table 10.1-3) and in children and adolescents (Table 10.1-4). The symptoms of an individual patient can overlap and change with time, but OCD has four major symptom patterns.

Table 10.1-3

Table 10.1-3

Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms in Adults

Table 10.1-4

Table 10.1-4

Reported Obsessions and Compulsions for 70 Consecutive Child and Adolescent Patients

Contamination. The most common pattern is an obsession of contamination, followed by washing or accompanied by compulsive avoidance of the presumably contaminated object. The feared object is often hard to avoid (e.g., feces, urine, dust, or germs). Patients may literally rub the skin off their hands by excessive hand washing or may be unable to leave their homes because of fear of germs. Although anxiety is the most common emotional response to the feared object, obsessive shame and disgust are also common. Patients with contamination obsessions usually believe that the contamination is spread from object to object or person to person by the slightest contact.

Pathological Doubt. The second most common pattern is an obsession of doubt, followed by a compulsion of checking. The obsession often implies some danger of violence (e.g., forgetting to turn off the stove or not locking a door). The checking may involve multiple trips back into the house to check the stove, for example. These patients have an obsessional self-doubt and always feel guilty about having forgotten or committed something.

Intrusive Thoughts. In the third most common pattern, there are intrusive obsessional thoughts without a compulsion. Such obsessions are usually repetitious thoughts of a sexual or aggressive act that is reprehensible to the patient. Patients obsessed with thoughts of aggressive or sexual acts may report themselves to police or confess to a priest. Suicidal ideation may also be obsessive; but a careful suicidal assessment of actual risk must always be done.

Symmetry. The fourth most common pattern is the need for symmetry or precision, which can lead to a compulsion of slowness. Patients can literally take hours to eat a meal or shave their faces.

Other Symptom Patterns. Religious obsessions and compulsive hoarding are common in patients with OCD. Compulsive hair pulling and nail biting are behavioral patterns related to OCD. Masturbation may also be compulsive.

Mental Status Examination

On mental status examinations, patients with OCD may show symptoms of depressive disorders. Such symptoms are present in about 50 percent of all patients. Some patients with OCD have character traits suggesting obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (e.g., excessive need for preciseness and neatness), but most do not. Patients with OCD, especially men, have a higher than average celibacy rate. Married patients have a greater than usual amount of marital discord.

Ms. K was referred for psychiatric evaluation by her general practitioner. On interview, Ms. K described a long history of checking rituals that had caused her to lose several jobs and had damaged numerous relationships. She reported, for example, that because she often had the thought that she had not locked the door to the car, it was difficult for her to leave that car until she had checked repeatedly that it was secure. She had broken several car door handles with the vigor of her checking and had been up to an hour late to work because she spent so much time checking her car door. Similarly, she had recurrent thoughts that she had left the door to her apartment unlocked, and she returned several times daily to check her door before she left for work. She reported that checking doors decreased her anxiety about security. Although Ms. K reported that she had occasionally tried to leave her car or apartment without checking the door (e.g., when she was already late for work), she found that she became so worried about her car being stolen or her apartment being broken into that she had difficulty going anywhere. Ms. K reported that her obsessions about security had become so extreme over the past 3 months that she had lost her job due to recurrent tardiness. She recognized the irrational nature of her obsessive concerns but could not bring herself to ignore them. (Courtesy of Erin B. McClure-Tone, Ph.D., and Daniel S. Pine, M.D.)

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Medical Conditions

A number of primary medical disorders can produce syndromes bearing a striking resemblance to OCD. The current conceptualization of OCD as a disorder of the basal ganglia derives from the phenomenological similarity between idiopathic OCD and OCD-like disorders that are associated with basal ganglia diseases, such as Sydenham’s chorea and Huntington’s disease. Neurological signs of such basal ganglia pathology must be assessed when considering the diagnosis of OCD in a patient presenting for psychiatric treatment. It should also be noted that OCD frequently develops before age 30 years, and new-onset OCD in an older individual should raise questions about potential neurological contributions to the disorder.

Tourette’s Disorder

OCD is closely related to Tourette’s disorder, as the two conditions frequently co-occur, both in individuals over time and within families. About 90 percent of persons with Tourette’s disorder have compulsive symptoms, and as many as two thirds meet the diagnostic criteria for OCD.

In its classic form, Tourette’s disorder is associated with a pattern of recurrent vocal and motor tics that bears only a slight resemblance to OCD. The premonitory urges that precede tics often strikingly resemble obsessions, however, and many of the more complicated motor tics are very similar to compulsions.

Other Psychiatric Conditions

Obsessive-compulsive behavior is found in a host of other psychiatric disorders, and the clinician must also rule out these conditions when diagnosing OCD. OCD exhibits a superficial resemblance to obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, which is associated with an obsessive concern for details, perfectionism, and other similar personality traits. The conditions are easily distinguished in that only OCD is associated with a true syndrome of obsessions and compulsions.

Psychotic symptoms often lead to obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors that can be difficult to distinguish from OCD with poor insight, in which obsessions border on psychosis. The keys to distinguishing OCD from psychosis are (1) patients with OCD can almost always acknowledge the unreasonable nature of their symptoms, and (2) psychotic illnesses are typically associated with a host of other features that are not characteristic of OCD. Similarly, OCD can be difficult to differentiate from depression because the two disorders often occur comorbidly, and major depression is often associated with obsessive thoughts that, at times, border on true obsessions such as those that characterize OCD. The two conditions are best distinguished by their courses. Obsessive symptoms associated with depression are only found in the presence of a depressive episode, whereas true OCD persists despite remission of depression.

COURSE AND PROGNOSIS

More than half of patients with OCD have a sudden onset of symptoms. The onset of symptoms for about 50 to 70 percent of patients occurs after a stressful event, such as a pregnancy, a sexual problem, or the death of a relative. Because many persons manage to keep their symptoms secret, they often delay 5 to 10 years before coming to psychiatric attention, although the delay is probably shortening with increased awareness of the disorder. The course is usually long but variable; some patients experience a fluctuating course, and others experience a constant one.

About 20 to 30 percent of patients have significant improvement in their symptoms, and 40 to 50 percent have moderate improvement. The remaining 20 to 40 percent of patients either remain ill or their symptoms worsen.

About one-third of patients with OCD have major depressive disorder, and suicide is a risk for all patients with OCD. A poor prognosis is indicated by yielding to (rather than resisting) compulsions, childhood onset, bizarre compulsions, the need for hospitalization, a coexisting major depressive disorder, delusional beliefs, the presence of overvalued ideas (i.e., some acceptance of obsessions and compulsions), and the presence of a personality disorder (especially schizotypal personality disorder). A good prognosis is indicated by good social and occupational adjustment, the presence of a precipitating event, and an episodic nature of the symptoms. The obsessional content does not seem to be related to the prognosis.

TREATMENT

With mounting evidence that OCD is largely determined by biological factors, classic psychoanalytic theory has fallen out of favor. Moreover, because OCD symptoms appear to be largely refractory to psychodynamic psychotherapy and psychoanalysis, pharmacological and behavioral treatments have become common. But psychodynamic factors may be of considerable benefit in understanding what precipitates exacerbations of the disorder and in treating various forms of resistance to treatment, such as noncompliance with medication.

Many patients with OCD tenaciously resist treatment efforts. They may refuse to take medication and may resist carrying out therapeutic homework assignments and other activities prescribed by behavior therapists. The obsessive-compulsive symptoms themselves, no matter how biologically based, may have important psychological meanings that make patients reluctant to give them up. Psychodynamic exploration of a patient’s resistance to treatment may improve compliance.

Well-controlled studies have found that pharmacotherapy, behavior therapy, or a combination of both is effective in significantly reducing the symptoms of patients with OCD. The decision about which therapy to use is based on the clinician’s judgment and experience and the patient’s acceptance of the various modalities.

Pharmacotherapy

The efficacy of pharmacotherapy in OCD has been proved in many clinical trials and is enhanced by the observation that the studies find a placebo response rate of only about 5 percent.

The drugs, some of which are used to treat depressive disorders or other mental disorders, can be given in their usual dosage ranges. Initial effects are generally seen after 4 to 6 weeks of treatment, although 8 to 16 weeks are usually needed to obtain maximal therapeutic benefit. Treatment with antidepressant drugs is still controversial, and a significant proportion of patients with OCD who respond to treatment with antidepressant drugs seem to relapse if the drug therapy is discontinued.

The standard approach is to start treatment with an SSRI or clomipramine and then move to other pharmacological strategies if the serotonin-specific drugs are not effective. The serotonergic drugs have increased the percentage of patients with OCD who are likely to respond to treatment to the range of 50 to 70 percent.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. Each of the SSRIs available in the United States—fluoxetine (Prozac), fluvoxamine (Luvox), paroxetine (Paxil), sertraline (Zoloft), citalopram (Celexa)—has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of OCD. Higher dosages have often been necessary for a beneficial effect, such as 80 mg a day of fluoxetine. Although the SSRIs can cause sleep disturbance, nausea and diarrhea, headache, anxiety, and restlessness, these adverse effects are often transient and are generally less troubling than the adverse effects associated with tricyclic drugs, such as clomipramine. The best clinical outcomes occur when SSRIs are used in combination with behavioral therapy.

Clomipramine. Of all the tricyclic and tetracyclic drugs, clomipramine is the most selective for serotonin reuptake versus norepinephrine reuptake and is exceeded in this respect only by the SSRIs. The potency of serotonin reuptake of clomipramine is exceeded only by sertraline and paroxetine. Clomipramine was the first drug to be FDA approved for the treatment of OCD. Its dosing must be titrated upward over 2 to 3 weeks to avoid gastrointestinal adverse effects and orthostatic hypotension, and as with other tricyclic drugs, it causes significant sedation and anticholinergic effects, including dry mouth and constipation. As with SSRIs, the best outcomes result from a combination of drug and behavioral therapy.

Other Drugs. If treatment with clomipramine or an SSRI is unsuccessful, many therapists augment the first drug by the addition of valproate (Depakene), lithium (Eskalith), or carbamazepine (Tegretol). Other drugs that can be tried in the treatment of OCD are venlafaxine (Effexor), pindolol (Visken), and the monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), especially phenelzine (Nardil). Other pharmacological agents for the treatment of unresponsive patients include buspirone (BuSpar), 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), L-tryptophan, and clonazepam (Klonopin). Adding an atypical antipsychotic such as risperidone (Risperdal) has helped in some cases.

Behavior Therapy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree