Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Management with Oral Appliance

James D. Geyer

Paul R. Carney

INTRODUCTION

Oral appliances (OAs) have been used for the management of snoring and, subsequently, for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) for many years (1). Devices designed for mandibular advancement (2,3) and retention of the tongue in an anterior position (4) were found to reduce upper-airway obstruction in sleep. With the publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s practice parameter for OA use in the therapy of snoring and OSA, OAs have become a well-accepted component of the OSA management paradigm (5,6).

CLINICAL EPIDEMIOLOGY

The epidemiology of OSA is covered in detail elsewhere in this text. A large percentage of the patients with OSA have mild to moderate disease. Since OA therapy is particularly suited to patients with mild to moderately severe OSA, sleep specialists should be aware of the potential of OA as a management tool.

Although the exact percentage of patients being treated with OA therapy is unknown, other therapies, particularly continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), appear to be used much more frequently. There are several possible explanations for this phenomenon, including the severity of cases presenting for treatment, the cost of OA, inadequate knowledge about OA among sleep specialists, and insufficient numbers of OA providers.

TYPES OF ORAL APPLIANCES

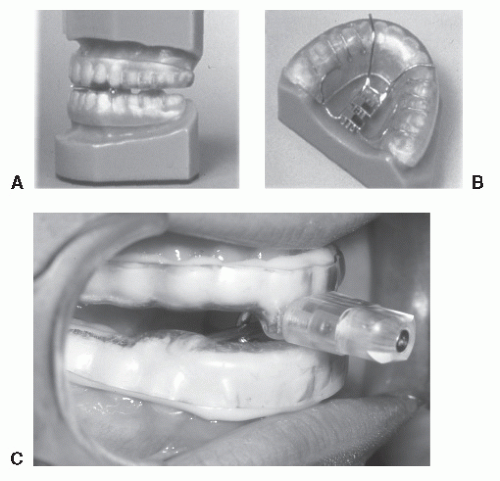

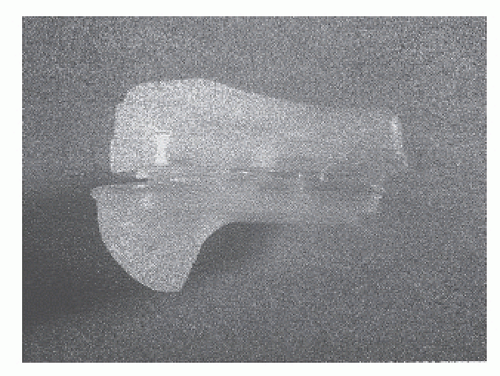

An OA is a device inserted into the oral cavity to modify the upper airway to ameliorate sleep-related breathing disorders (SRBDs). These devices are distinct from the more commonly used “activator” appliances used by dentists to modify dentition. The most common OA design type consists of attachments to the mandibular and maxillary dental arches with varying degrees of bite opening and mandibular advancement relative to the maxilla. These mandible-advancing devices (MADs) are shown in Figures 22-1 and 22-2. Although these may be in a fixed position with a predetermined advance, they are more frequently used with an adjustable advance, changed according to the patient’s response. Tongue-retaining devices hold the tongue anterior in the oral cavity. Several other approaches, such as palatal lifters and tongue depressors, have not been successful either because of limited efficacy or patient intolerance.

MECHANISM FOR ORAL APPLIANCES

OAs are presumed to treat SRBD by increasing the size of the airway. Cephalometric studies support this hypothesis. Not only do MAD systems bring the tongue forward and increase pharyngeal volume, there also appears to be an increase in the retropalatal space and a change in the shape of the oral airway. Although most of these studies have been performed on patients who are awake, one study

showed similar airway effects of mandibular advancement in anesthetized subjects (7).

showed similar airway effects of mandibular advancement in anesthetized subjects (7).

Other factors may contribute to the efficacy of OA, including increased muscle tone, enhanced airway compliance, and mandibular posture. OA systems increase the tone of the displaced upper-airway muscles as measured by electromyography (8). Furthermore, the critical closing pressure of the relaxed airway is decreased (enhanced compliance) with MAD systems (9). Stabilization of the mandibular posture with OA decreases the downward rotation of the mandible with sleep. This diminishes the movement of the genioglossus into the oropharynx and retropharynx (10).

EFFICACY OF ORAL APPLIANCES

OA therapy often improves mild to moderate OSA. It is very important to monitor patients closely since the OA may not control the OSA, and in some cases, the OSA may actually worsen. Most patients have reduced or abolished snoring, reduction in apnea—hypopnea index (AHI), and improvement in oxygen saturation. However, it is possible for only the snoring to improve, diminishing one of the warning indicators of the OSA. The efficacy of OA from several different studies is reviewed in Table 22-1.

Interpretation of the data regarding OA therapy is made all the more challenging because of a variable definition of treatment success. More recent studies define success as a relief of symptoms and a reduction of AHI to 10 to 15 per hour. Unfortunately, this means that success has been defined in a way that allows significant residual sleep apnea. Modern adjustable and titratable appliances are, however, clearly superior to the older fixed devices (Table 22-1). OA are much less efficacious in patients with severe OSA (14,15).

COMPARISONS OF ORAL APPLIANCES TO OTHER TREATMENT MODALITIES

Multiple studies have shown that CPAP is extremely efficacious in controlling snoring and OSA, whereas OA therapy may leave some patients with residual OSA (Table 22-2). Conversely, compliance with OA appears to be superior to CPAP (12).

OA was compared with surgical management with uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) in one randomized controlled trial. The findings revealed an increased number of cases with treatment failure in the surgery group and a better overall result in the OA patients at 4 years (normal AHI at 1 and 4 years: OA, 78%, 63%; UPPP, 51%, 33%; p < 0.05) (21). This study suggests that OA is superior to UPPP for the management of OSA.

Careful selection of patients for a particular therapy modality is vital. The sleep specialist should not carry a bias toward a particular therapy.

COMPLICATIONS AND SAFETY

As with all treatments, OA has potential complications (Table 22-3). There is the risk of significant occlusal change with long-term use. After several years of use, OA devices were associated with an increased risk of pain (temporomandibular joint (TMJ), dental pain, or myofascial pain) in 25% and dental malocclusion in 14% (20). Many patients considered these changes relatively minor and discontinuation of the OA was rare (20,22).

Cephalometric studies have shown significant tilting of incisors, forward at the mandible and backward at the maxilla, appearing after 12 to 18 months of use (23).

Cephalometric studies have shown significant tilting of incisors, forward at the mandible and backward at the maxilla, appearing after 12 to 18 months of use (23).

TABLE 22-1 EFFICACY OF ORAL APPLIANCE ON OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA: SELECTED PUBLICATIONS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree