Chapter 19 Occipital Neurostimulation

Stimulation of the occipital nerve, which originates from the C2 nerve root, is a valuable tool in treating cervicogenic headache, occipital neuritis, chronic migraine, and chronic cluster headache.

Stimulation of the occipital nerve, which originates from the C2 nerve root, is a valuable tool in treating cervicogenic headache, occipital neuritis, chronic migraine, and chronic cluster headache. Current prospective randomized studies are pending to access the evidence-based impact of this therapy on migraine.

Current prospective randomized studies are pending to access the evidence-based impact of this therapy on migraine. In some cases ONS may be combined with stimulation of other cranial nerves to avoid the need for more invasive intracranial procedures.

In some cases ONS may be combined with stimulation of other cranial nerves to avoid the need for more invasive intracranial procedures.Indications

ONS has been used successfully in the treatment of occipital neuralgia1–4 and many primary headache disorders such as migraine,5 transformed migraine,4 cluster headache,5–9 and hemicrania continua.6,10 Few reports also demonstrated its efficacy in secondary headache disorders, including cervicogenic headache,11 C2-mediated headaches,12 posttraumatic,13 and postsurgical headaches.14

Mechanism of Action

The most accepted mechanism of action is that stimulation of the distal branches of C2 and C3, being the peripheral anatomical and functional extension of the trigeminocervical complex, may inhibit central nociceptive impulses.15 Positron emission tomography (PET) scan studies showed increased regional cerebral blood flow in areas involved in central neuromodulation in chronic migraine patients with occipital nerve electrical stimulation.16 Additional functional imaging may further define the exact mechanism of action as these studies become more widely available in multicenter studies.

Efficacy and Safety

Recently the preliminary results of a multicenter prospective randomized single-blind controlled feasibility study that was conducted to examine the safety and efficacy of ONS for treatment of intractable chronic migraine were reported.17 Patients who responded favorably to occipital nerve block (ONB) were randomized 2 : 1 : 1 to adjustable stimulation (AS), preset stimulation (PS), or medical management (MM). Those who did not respond to ONB formed an ancillary group (AG).

Reduction in overall pain intensity was 1.5 (AS), 0.5 (PS) (p = 0.076), 0.6 (MM) (p = 0.092), and 1.9 (AG) (p = 0.503). Responder rate was 39% (AS), 6% (PS) (p = 0.032), 0% (MM) (p = 0.003), and 40% (AG) (p = 1.000). The authors concluded that ONS may be a promising treatment for intractable chronic migraine and ONB may not be predictive of response to ONS.17

Anatomy

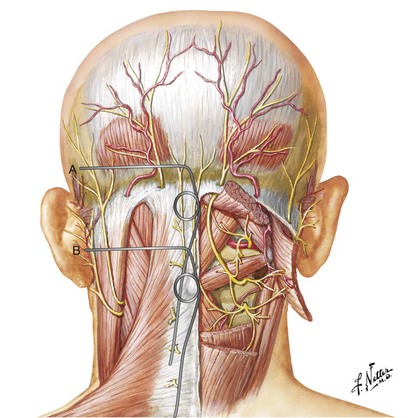

The GON arises from the C2 dorsal ramus and curves around the inferior border of the inferior oblique muscle (IOM) to ascend on its superficial surface between the IOM and the semispinalis capitis at the C1 level. Then it penetrates the semispinalis capitis and invariably the splenius muscle to end subcutaneously near the nuchal line by penetrating the trapezius muscle or its apponeurosis.18–20 There is considerable anatomical variation in the course of the GON. Bovim and colleagues18 found that the GON pierces the trapezius in nearly half the subjects; however, others have described a much lower likelihood of penetration of the trapezius muscle. The GON was invested in the aponeurosis of the trapezius at its insertion.19,20

The GON usually penetrates the semispinalis capitis muscle fibers at a distance between 2 and 5 cm caudad to the occipital protuberance.18 More cranially it may also penetrate the trapezius muscle fibers or aponeurosis, becoming superficial between 5 and 18 mm below the intermastoid line.19

Technique for Occipital Neurostimulation

The technique was originally reported by Weiner and Reed in 1999.1 Earlier reports involve placement of the leads subcutaneously at the C1 level. The stimulator lead can be directed medially from a lateral entry point medial and inferior to the mastoid process1,4,9,12,21,22 or laterally from a midline entry point.2,7,11,13,23,24

Level and Depth of Lead Placement

The level and depth of lead placement are crucial for a successful ONS trial. Placing the leads too superficially risks failure of nerve stimulation and lead erosion through the skin or patients experiencing unpleasant burning sensations. On the other hand, leads placed too deep risk stimulating posterior neck muscles and causing unpleasant muscle spasms.25

Positioning the stimulator lead subcutaneously at the C1 level places it at a significant distance from the nerve, with the posterior neck muscles (mainly trapezius and semispinalis capitis) intervening. Thus, to stimulate the GON itself, the intervening muscles are likely to be recruited as well (Fig. 19-1).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree