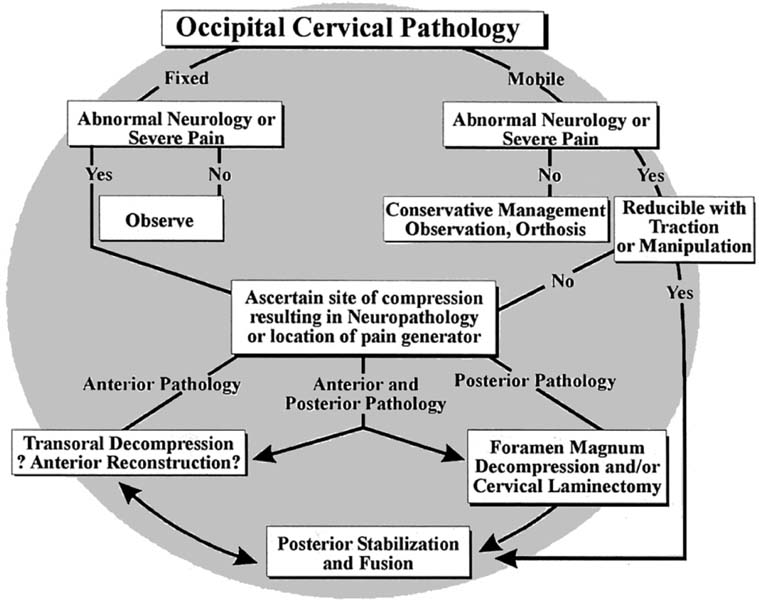

1 Occipitocervical Junction 1. To treat pathology at the craniocervical junction (CCJ), the degree of instability present, and the type and extent of the neurologic involvement must be considered before conservative or surgical intervention is proposed (Fig. 1–1). 2. The specific goals for surgery vary depending on the pathology to be addressed. In general, surgery is performed to alleviate pain, correct deformities, stabilize instabilities, and decompress the neuraxis. 3. The final surgical outcome must result in near anatomic alignment, decompression of the neuraxis, and effective CCJ stabilization to counteract the tendency for craniocervical kyphosis, and it must promote a solid fusion (Fig. 1–2). The pathologic entities that may affect the craniocervical junction are numerous (Table 1–1). Often attention is drawn to the craniocervical junction only after the onset of CCJ instability, which results in pain or neurologic deficits. Neurologic deficits typically involve either myelopathy or lower cranial nerve deficits or both. Radiographic investigation begins with plain x-rays for evaluation of standard radiographic landmarks. These studies are supplemented with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), and CT myelograms and myelographic studies as needed. 1. Treat established or impending neurologic injury to the brainstem or spinal cord. 2. Reduction and stabilization of instability [atlantoaxial subluxation (AAS), rheumatoid arthritis (RA)]. 3. Correction of deformity [atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation (AARS) and fixed CCJ kyphosis]. 4. Alleviate pain [osteoarthritis (OA), tumors]. 5. Debridement (infection, tumors). 1. Severe osteopenia (difficult to stabilize postop, halo may be required). 2. Chronic, severe myelopathy or paralysis (neurology unlikely to be reversible). 3. Nonambulatory: Ranawat III B (unlikely to regain ambulatory status if long-standing, 50% morbidity and mortality rate in RA). 4. Insufficient subspecialty experience on surgical team. 5. Inability of patient to cooperate with postoperative regime. 1. Transoral approach allows simple direct access to CCJ from mid-clivus to C2–C3. 2. Open-door maxillotomy allows access from upper clivus to C3. 1. Risk of infection (probably no higher than in posterior approach). 2. Difficult to close durotomies. 3. May be difficult to achieve stable instrumentation and may not be suitable as a stand-alone procedure. 4. Open-door maxillotomy requires oral surgeon or skull base surgeon as an additional team member. 1. Quick. 2. Does not require manipulation of anterior cervical visceral structures. 3. Can visualize entire CCJ and is extensile. 4. CCJ and extensile constructs possible, good visualization of osseous fixation points. 5. Extensive bed for occipital, cervical, and thoracic fusion is available. 6. Anterior decompression may be achieved indirectly via reduction of mobile CCJ kyphosis. Figure 1–1

Decompression and Fusion

Goals of Surgical Treatment

Diagnosis

Indications for Surgery

Relative Contraindications

Advantages/Disadvantages

Anterior Approaches: Advantages

Anterior Approaches: Disadvantages

Posterior Approaches: Advantages

Cranial cervical junction algorithm.

Rheumatoid arthritis |

Infection |

Trauma |

Down syndrome |

Congenital anomalies |

Osteoarthritis |

Osteogenesis imperfecta |

Achondroplasia |

Tumor |

Morquio’s disease |

Iatrogenic instability |

Dwarfing syndromes |

Posterior Approaches: Disadvantages

1. CCJ pathology usually has significant anterior component.

2. Neuroaxial decompression in fixed kyphosis must be performed anteriorly.

3. CCJ deformity, typically kyphosis, may be difficult to treat via a posterior only approach.

4. Lack of anterior column support may contribute to failure of posterior instrumentation.

Procedure

Transoral Approach

The transoral approach is the preferred method to directly access the anterior craniocervical junction. Access can be gained from the inferior third of the clivus to the superior aspect of C3. Proximal extension can be achieved by splitting the soft palate in the midline with retraction of the uvula superiorly. Additional superior extension can be achieved by osteotomy of the hard palate. Caudal extension can be achieved by splitting the tongue either in the midline without mandibular osteotomy or in the midline with osteotomy of the mandible, and caudal retraction of the tongue. In this way, surgical exposure can be achieved from the mid-clivus to C3.

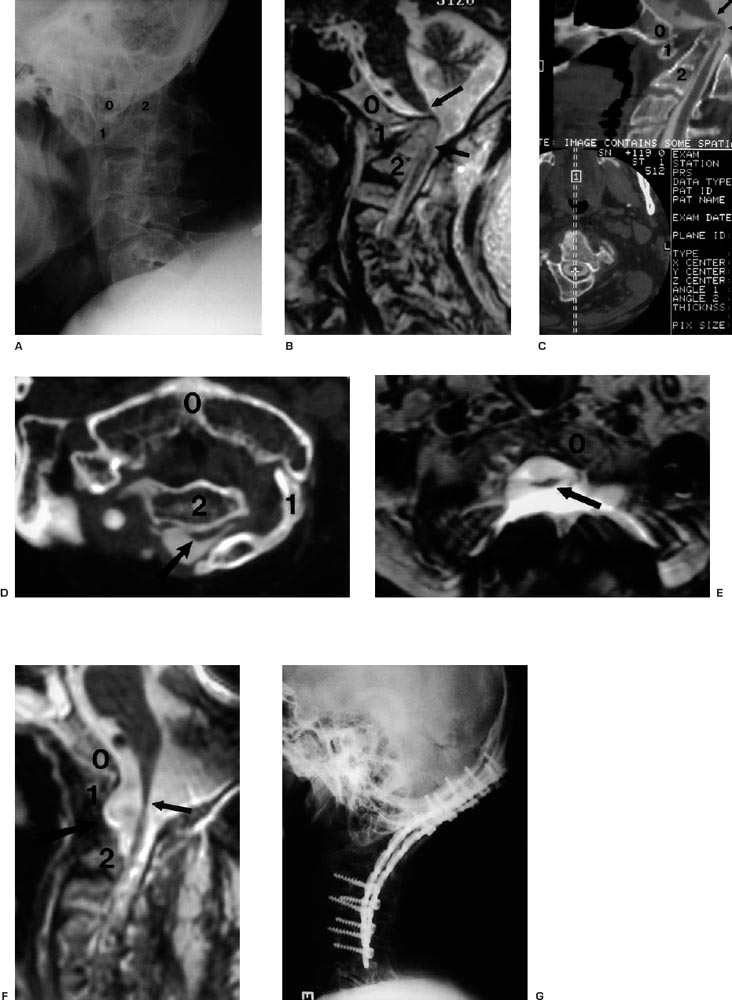

Figure 1–2

(A–G) Illustrative case. (See text for complete discussion.)

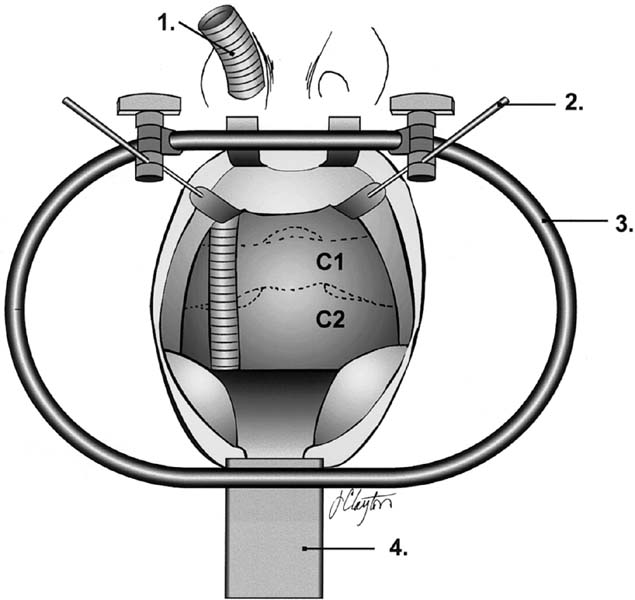

Figure 1–3

Transoral retractor positioning (anterior). 1, Armored nasotracheal tube; 2, soft palate retractors; 3, perioral ring; 4, tongue retractor. (See Color Plate 1–3.)

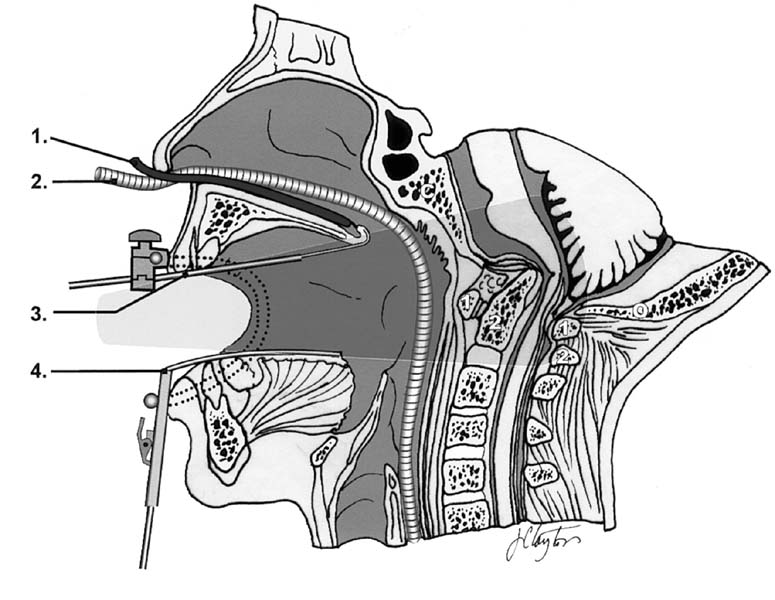

Figure 1–4

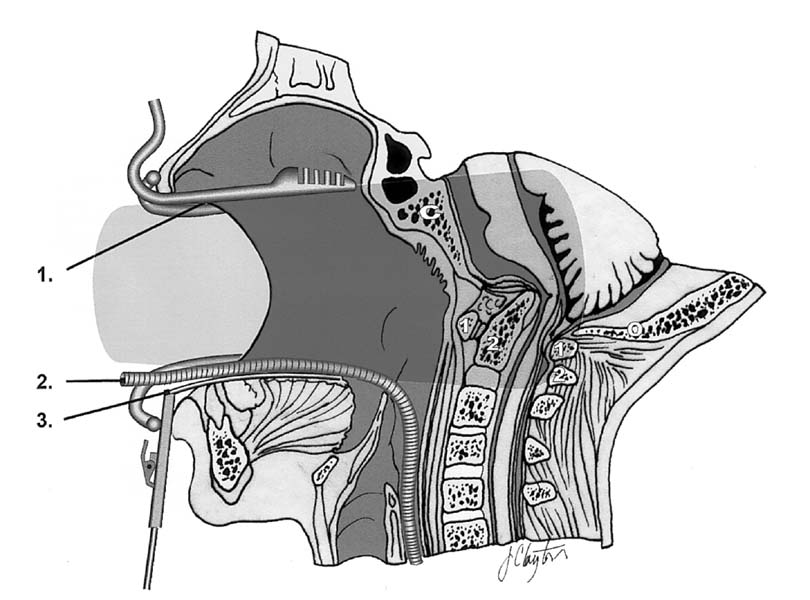

Transoral retractor positioning (lateral). 1, Red rubber catheter; 2, armored nasotracheal tube; 3, soft palate retractor; 4, tongue retractor. (See Color Plate 1–4.)

Figure 1–5

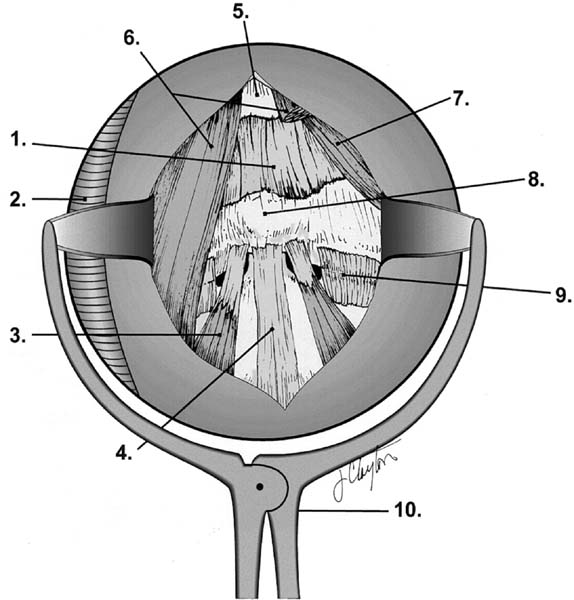

Retropharyngeal anatomy and retractor. 1, anterior atlanto-occipital membrane; 2, armored nasotracheal tube; 3, longus colli muscle; 4, anterior longitudinal ligament; 5, clivus; 6, longus capitis muscle; 7, rectus capitis anterior muscle; 8, anterior tubercle of C1; 9, lateral atlantoaxial joint capsule; 10, retropharyngeal soft tissue retractor. (See Color Plate 1–5.)

Figure 1–6

Open-door maxillotomy (lateral). 1, Maxillotomy retractor; 2, armored nasotracheal tube; 3, tongue retractor. (See Color Plate 1–6.)

Figure 1–7

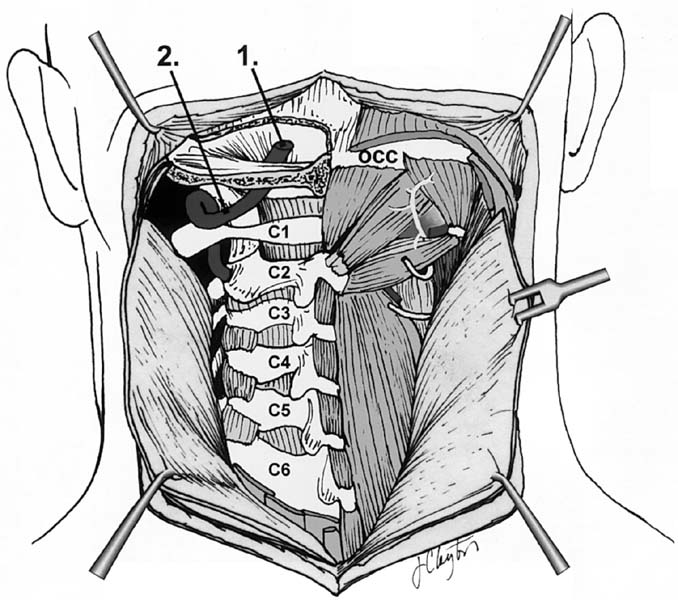

Posterior dissection. 1, Intracranial vertebral artery; 2, extracranial vertebral artery. (See Color Plate 1–7.)

Figure 1–8

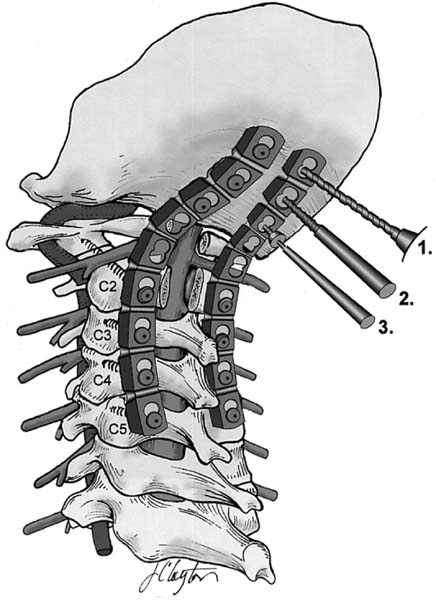

Posterior instrumentation. 1, Drill; 2, screw tap; 3, screw driver. (See Color Plate 1–8.)

Preparation and Preoperative Assessment for Transoral Surgery

Careful preoperative evaluation of the oral cavity is mandatory to identify sepsis. If necessary, cultures and sensitivities may be performed. The condition of the teeth must be evaluated. In those patients with significant dental problems or in the edentulous patients, special protective dental guards may be necessary. Soft dental molds may be useful to protect the teeth and gums from the rostral and caudal retractors. If the interdental distance is less than 25 mm with the patient’s mouth maximally opened, it is unlikely that a conventional transoral procedure will be possible. Patients with large, thick tongues (Down syndrome) may also present a challenge to retractor positioning.

Anesthesia

For most transoral procedures, tracheostomy is not necessary. Either an oral endotracheal or an armored nasal tracheal tube may be used. The armored nasal tracheal tube is preferred. It enters nasally, out of the operative field, and is easily retracted laterally intraorally by the transoral retractor system CODMAN. Patients remain intubated for several days postsurgery to allow retropharyngeal swelling to subside. Nasotracheal tubes are more comfortable during this period than oral tracheal tube. Awake intubation may be necessary for those patients with an unstable CCJ or tenuous neurologic function.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree