Personal narrative

My dream was to be an artist; however, this was seen by my family as indulgent and economically risky. So I became an occupational therapist, bringing with me a curiosity about multiple meanings of experiences. I was especially curious about mental illness, having explored the work of Jung whilst studying at school (Jung et al., 1995). The bridge he suggested between symbols and intrapersonal psychology was something I wanted to continue to explore.

Immersed in Jung, in 1980 I had my first experience of psychiatry when I visited the hospital where a friend had been admitted. I went to see the occupational therapy department, which was also home to a rabbit, and I was struck by the image of the caged animal in an asylum. I met an occupational therapy student there, and she warned me ‘don’t think this is occupational therapy, it’s not’ and I was puzzled to know the difference. It looked as if the people in the department were better off than the ones outside, roaming the grounds or behind the grey walls and windows of the wards. These thoughts stayed with me as I progressed through the course, qualifying in 1984. Over the next 18 years I worked mainly as a senior occupational therapist in hospitals and in the community, in mental health and physical disability settings. I did some research (Bryant, 1991, 1995; Bryant et al. 2004, 2005), had two children and continued to work part time as they grew up.

My overriding passion has been to explore how people who are routinely silenced and ignored in everyday care settings can be given a voice. This emphasis on the everyday is critical. My practice and research must impact the everyday to make a difference. This means exploring multiple interpretations of experience, just as I have done as an artist. There are many ways to paint a portrait and there are many ways for people to express their hopes. Enabling people to do this involves working in a risky, creative way. This is what has kept me an occupational therapist. I have found that one of the most satisfying ways of exploring multiple interpretations is to do research.

My first experience of working in the community mental health setting was when the NHS and Community Care Act (1990) was beginning to impact on services. I spent half my time working with individuals requiring short-term interventions and the other half of my time developing day services in the local area for people with longer-term problems. The expectation was that day services would take place in the local community. There were two beliefs in relation to this. The first belief was that people would use them as a stepping stone to being involved in the community, eventually feeling confident and well enough to belong to other groups that were open to everyone. The second belief was that professional involvement was required only initially to get the day services going and foster an emphasis on social contact and meaningful occupation. It was important not to create dependency, and so I was expected to share responsibility with service users for leading the services.

These beliefs reflected the government policies of the 1980s, which built on a political and clinical desire to increase community services, justified both in terms of economics and deinstitutionalisation. My post involved balancing resources between people newly referred and those who used services over the long term. At the time, the main way of engaging with long-term service users in the community was through out-patient appointments with psychiatrists, depot injections or day services. The views that day services were a stepping stone to the community, or would become service user led, were challenged by this group of people. Many were already known in the community and, at best, had established social networks. They knew far more about the local community than I did, and what they valued was the opportunity to meet with each other. Research at the time reflected this (Brewer et al., 1994; Bryant, 1995).

These issues arose again in my master’s research (Bryant et al., 2004, 2005) and the concept of occupational alienation emerged as a useful foundation for further exploration. This chapter explores occupational alienation (Wilcock, 1998) pointing to the absence of creativity and meaning in occupation as a factor in mental ill health. I believe that the current emphasis on the outcomes of interventions, rather than the processes, generates increased occupational alienation for service users.

Occupational alienation defined

Occupational alienation has been defined as a ‘sense of isolation, powerlessness, frustration, loss of control, and estrangement from society or self as a result of engagement in occupation that does not satisfy inner needs’ (Wilcock, 2006, p. 343). The concept was proposed by Wilcock (1998) in relation to the theory that health was dependent on a person engaging in meaningful occupations. She considered what might interfere with this process, identifying the occupational risk factors of occupational deprivation, alienation and imbalance.

Occupational therapists in the USA also sought to develop an occupational perspective explaining ill health in terms of occupation (Zemke & Clark, 1996; Yerxa, 2000). This occupational perspective demanded a broader definition of occupation, to incorporate everything a person does in his or her life (Wilcock, 1998). From this standpoint, it was possible to look at how the things people do shape their identity and roles in social contexts. It also enabled environmental factors to be acknowledged as determinants of occupational performance.

Wilcock’s (1998) conception of occupational alienation emphasised that demands of everyday life required people to do things that lacked personal meaning, such as boring and repetitive tasks that isolate people from each other (Wilcock, 2006). Embedded in this are three elements:

- absence of personal meaning or meaninglessness, an internal state;

- absence of opportunities to be creative and control meaningful occupations and tasks;

- social isolation or alienation arising from the shared perception of meaningless and repetitive occupations and tasks.

These three dimensions in relation to mental health will be explored, illustrated by ordinary encounters from my life.

In the post office

Until recently, I lived and worked in the same locality; so when I see a person I recognise I am not sure where I know the person from. I was waiting in the local post office when I noticed two men in front of me, one with a pension book and the other man who I immediately recognised but could not place. He was tall, wore a broad rimmed hat and had dark hair curling over his shoulders. I knew when he turned towards me that he would be wearing reflective sunglasses and he would have a beard. He was thinner than I remembered. His voice was authoritative: ‘Can’t understand why things have to be changed. There was nothing wrong before.’ I was interested to see what he was complaining about. The man behind the counter had a resigned air. As the man in the hat left, I was overwhelmed by the stale smell of his unwashed clothes. I would not choose to sit next to him on a train for an hour. And this set me thinking about exclusion. How realistic is it to expect people with mental health problems to become integrated into the community? To what extent can I live peacefully alongside someone who does not wash their clothes and argues in post offices?

The conversation in the post office resumed and the man with the pension book spoke about the man in the hat. It seemed that he had been questioning the need for a receipt, ‘more bits of paper’, and the pension man could not understand his ungratefulness or his bad mood. What was wrong with a scrap of paper? It could be useful, if something went wrong. When something goes wrong, for me, it is inevitably an effort to locate that crucial scrap of paper. And I could see that, for all of us, this episode meant different things. The scrap of paper, for the man in the hat, may have been another burden or another representation of officialdom. The man with the pension book was interested in his reaction, but incredulous. The man behind the counter was resigned and I was thinking about my research.

Critiquing the concept of occupational alienation

It is possible to trace alienation through this experience, linked with the stale smelling clothes, scraps of paper and each of our responses. However, in relation to alienation, it has to be questioned whether the occupational label is useful or distracting. It could be argued that alienation is an emotional state, not related to what people do. Understandings from psychiatry support a concept of alienation being a state of mind; for example, persons with psychosis interpreting their experience in a way not widely shared (Pilgrim, 2005). These persons then become alienated from others, because they have a different view of their experience, or they are alienated from themselves, because their interpretation is at odds with reality or the accepted view of their experience. In contrast, Laing (1967) proposed that alienation is a universal human experience.

Two aspects of alienation deserve further exploration. The first is alienation in a social sense. People can be alienated from others because they see their experience in a different way. Thus, alienation is seen as an alternative to belonging and relates to social inclusion, which promotes belonging as a means of promoting mental health (Bryant et al., 2004). The second aspect of alienation relates to creativity. Returning to the man in the hat, if he was someone who had experienced delusional beliefs about his social status he perceived that this belief was not shared by others, he might feel socially alienated. His interactions could become aggressive and negative, his isolation leading him to neglect those self-care occupations, which would facilitate his belonging. He would be driven to live and do things in different ways because of his sense of a gap between what he wanted and what he was experiencing. He would have to create new possibilities to survive. Beyond mental illness, Lacan’s theories of creativity and alienation support this concept (Stavrakakis, 2002). Creative acts arise from an internal sense of alienation, the gap between what is desired and what is actually experienced. A deeper analysis has been offered by Mann (2001).

Similarly, Wilcock’s (1998) theory suggested that occupational alienation was signified by a split between the things we have to do and the things we desire to do. She believed that occupational alienation was a key determinant of ill-health, associated with industrialisation. She used a Marxist understanding of alienation (Wilcock, 1998, 2006). Marx (1975) wrote extensively about alienation, linked with the dehumanising effects of industrial production. His analysis of alienation recognised three forms: of the individual from the products of his or her work, from the process of the work and from others. Occupational alienation derives from this. If the products of an individual’s activities do not directly meet his or her personal needs, or directly meet the needs of another person known to the originator, the individual is engaged in doing something that is not directly meaningful, and yet he or she continues to do this to live. Thus, the individual is alienated from the process of the occupation as well as from its product. Finally, the individual is alienated from others, being viewed by others in terms of their role in the process of production. Marx’s utopian vision to overcome alienation involves human needs being met through a direct transaction between one person and another, meeting needs without the alienating intermediary of money.

So occupational alienation can be seen as a human response when meanings change and occupational forms shift, facilitating the emergence of new meanings and ways of doing. As such it is a significant concept for advancing practice in mental health, where this process is ongoing, as people engage with their problems, avoid them, succumb to them and recover from them. New meanings and ways of doing, or occupational forms, emerge and indicate recovery or relapse.

Efforts to facilitate this process can be seen as overcoming occupational alienation. Setting up opportunities for individuals to create meaningful ways of doing things for themselves may reduce occupational and social alienation, increasing their sense of belonging in the wider social context. Social inclusion is a dynamic process of negotiation between individuals and society, not an outcome in itself. Recognising the shifting meanings applied by the individual and society means that occupational alienation is an intrinsic part of the process of creating new possibilities for belonging. For example, Aggett and Goldberg (2005) describe the group of people they worked with as pervasively alienated, being isolated, inaccessible, invisible, antagonistic and living a rigidly patterned lifestyle. They avoided contact with mental health services, only emerging when symptoms became uncontrollable or housing issues arose. Their sense of alienation often extended to the staff of community mental health teams, preventing creative approaches being developed (Aggett & Goldberg, 2005). A starting point for developing meaningful contact was concerned with the occupational form: doing everyday occupations predictably and in a way with which the service user found meaningful was essential.

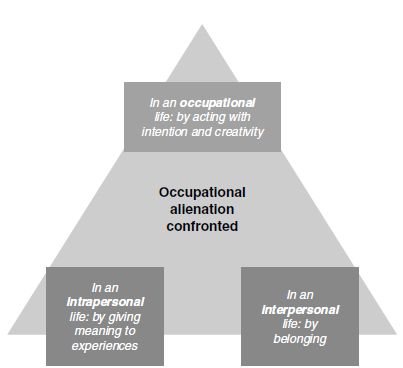

Bryant et al. (2004) suggested three dimensions of occupational alienation, using the metaphor of living in a glasshouse, which places a barrier between the individual and society. This blocks a sense of belonging, being alienated from others (interpersonal). Vulnerability, represented by the glasshouse, limits the occupations that the person can engage in (occupational). This in turn impacts on the person’s sense of self, causing a sense of alienation (intrapersonal). This is illustrated in Figure 7.1.

In the hardware shop

Returning to the man described earlier, I often see him locally but rarely in town. In a crowded shop where the layout had recently changed, I was disorientated; it took me a few minutes to work out where to pay for my purchase. My confusion was compounded by the presence of this man. His appearance was similar but now he wore a long black raincoat. On this occasion his clothes did not smell. He was in the queue behind another man who was being served, and he did not appear to have a purchase to pay for. So I smiled and asked, ‘Are you queuing to be served?’ He muttered, ‘No, no, I’m not queuing.’ He walked away as the other man had completed his transaction. They greeted each other and walked out of the shop together. Who was this second man? A friend, partner or support worker?

Figure 7.1 Vulnerability, represented by the glasshouse, limits the occupations that the person can engage in (occupational alienation confirmed). This in turn impacts on the person’s sense of self, causing a sense of alienation (intrapersonal).