Front Neurol Neurosci. Basel, Karger, 2014, vol 33, pp 82-102 (DOI: 10.1159/000351905)

______________________

Symptoms of Transient Ischemic Attack

Jong S. Kim

Stroke Center and Department of Neurology, University of Ulsan, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, South Korea

______________________

Abstract

Transient ischemic attack (TIA) is a cerebrovascular disease with temporary (<24 h) neurological symptoms. The symptoms of TIA patients are largely similar to those of ischemic stroke patients and include unilateral limb weakness, speech disturbances, sensory symptoms, visual disturbances, and gait difficulties. As these symptoms are transient, they are frequently evaluated based on patients’ subjective reports, which are less precise than those of patients with stroke whose longer-lasting symptoms and signs can be reliably assessed by physicians. Some symptoms, such as monocular blindness, are much more common in TIA than in stroke, and limb shaking occurs almost exclusively in TIA patients. On the other hand, symptoms like hemivisual field defects or limb ataxia are under-appreciated in TIA patients. These transient neurological symptoms are not necessarily caused by cerebrovascular diseases, but can be produced by a variety of non-vascular diseases. Careful history taking, examination, and appropriate imaging tests are needed to differentiate these TIA mimics from TIA. Each TIA symptom has a different specificity and sensitivity, and there has been an effort to assess the outcome of the patients through the use of specific clinical features. On top of this, recent developments in imaging techniques have greatly enhanced our ability to predict the outcomes of TIA patients. Perception or recognition of TIA symptoms may differ according to the race, sex, education, and specialty of physicians. Appropriate education of both the general population and physicians with regard to TIA symptoms is important as TIAs need emergent evaluation and treatment.

Copyright © 2014 S. Karger AG, Basel

Transient ischemic attack (TIA) is a cerebrovascular disease with temporary (<24 h) neurological symptoms. As the symptoms are transient, patients are frequently evaluated based on their subjective reports, which are less precise than those of stroke patients who are assessed by physicians in the presence of their symptoms/signs. While certain symptoms, such as hemivisual field loss or limb ataxia, are underappreciated, other symptoms, such as monocular blindness or limb shaking, occur much more frequently, or even exclusively, in TIA patients. Therefore, differences remain in the prevalence and characteristics of symptoms between TIA and stroke.

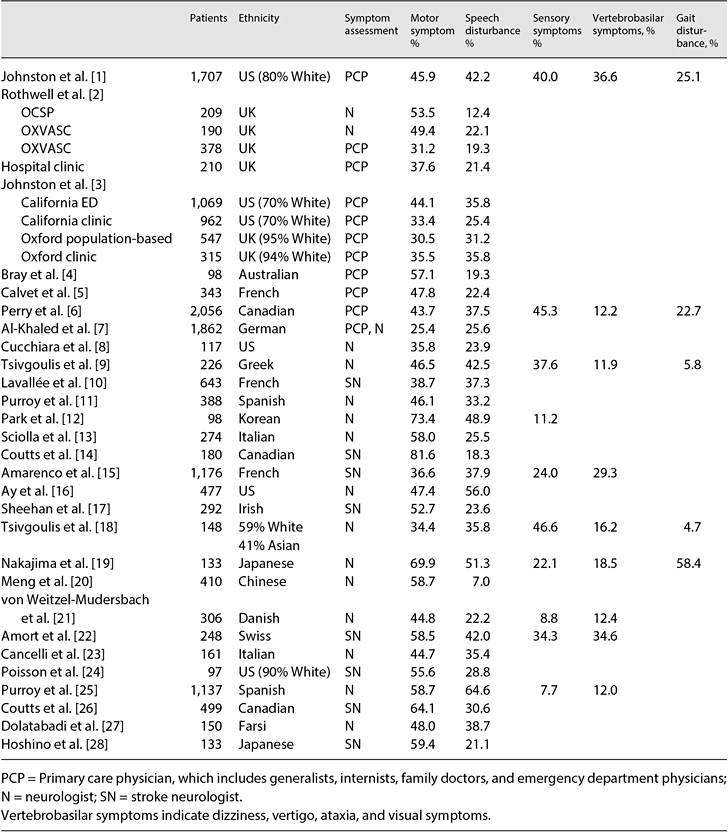

Table 1 lists the frequency of TIA symptoms in recent major studies [1–28]. Of these, unilateral motor symptoms are the most frequent, followed by speech disturbances and sensory symptoms. In this chapter, these symptoms will be described in detail. The sensitivity and specificity of these symptoms, TIA mimics, and problems in the perception and recognition of TIA symptoms will also be discussed.

Transient Ischemic Attack Symptoms

Hemiparesis and Other Types of Motor Dysfunction

As in patients with stroke, motor dysfunction is the most common manifestation of TIA (table 1). The most frequently observed topography is a weakness involving the arm, leg and face. The severity varies from severe, such as a complete inability to use limbs, to a subtle clumsiness of the hand or fingers. Although mild symptoms are more common in TIA patients, repeated occurrence of motor TIAs should be taken seriously because patients may eventually develop infarcts associated with severe motor dysfunction [29].

The somatic motor symptoms are usually attributed to the transient dysfunction of the pyramidal tract due to ischemic insult. However, because the symptom usually has disappeared or improved by the time the patient is seen by a physician, the underlying neurological problems are often difficult to correctly assess. It should be borne in mind that a subjective ‘weakness’ in the limbs may also be caused by dysfunction in the sensory (usually proprioceptive), coordination or extrapyramidal systems. Accordingly, the prevalence of ‘motor dysfunction’ in TIA patients is likely to be exaggerated. Moreover, even if patients only report motor problems, it does not necessarily mean that they did not have other neurological dysfunctions. For example, when tested in the emergency department, patients occasionally show decreased sensory perception in paralytic limbs that they had previously not noticed.

As in patients with stroke, topography involving the face, arm and leg together on one side is the most common. However, focal embolic ischemic events in the small area of the motor cortex may produce isolated weakness in the arm or the face, while involvement of a more medial part (i.e. the anterior cerebral artery territory) may produce weakness limited to the leg or the foot (fig. 1). In clinical practice, even if patients have hemiparesis involving the face, arm and the leg, they may recognize weakness in only a part of the body according to their situation when the symptoms occur. For example, patients who develop TIA while walking may report that they had symptoms only in the leg, whereas patients may only report arm weakness if the TIA develops while they are sitting down and using their arms.

Occasionally, patients complain of bilateral weakness. As this may be attributed to a severe vertebrobasilar disease, the accompanying symptoms and signs, such as dizziness, vertigo, diplopia or visual dimness, should be carefully examined. Severe, bilateral steno-occlusive disease in the anterior circulation may also produce bilateral weakness. In clinical practice, this symptom is more often associated with unilateral cerebrovascular diseases of the anterior circulation; the presence of uncrossed pyramidal fibers may partly explain this phenomenon. In addition, patients may perceive sudden gait impairment as bilateral leg weakness when it is actually due to unilateral weakness.

Table 1. Frequency of TIA symptoms in recent major studies

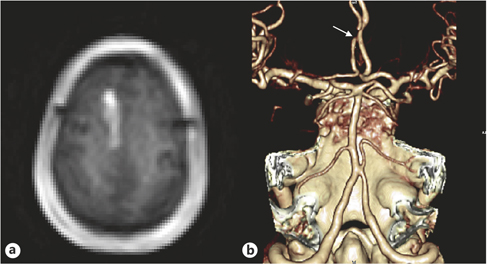

Fig. 1. A 79-year-old hypertensive woman developed weakness on the left leg lasting <1 min, when she could not walk and had to sit down for a while. The episodes occurred approximately once a day. One month later, she developed prolonged left leg weakness associated with dysarthria and urinary incontinence. DWI showed an acute infarction in the right anterior cerebral artery territory (a), and CT angiography showed severe focal stenosis on the right anterior cerebral artery (arrow; b).

There are patients who show repeated, stereotyped motor (or occasionally sensorimotor) hemiparesis involving the face, arm and leg simultaneously with no cortical signs such as aphasia or neglect. This is often described as ‘capsular warning syndrome’ because the affected region is probably the subcortical area (i.e., internal capsule) or, less often, the pontine base [29, 30]. The presumed mechanism is a repeated hemodynamic compromise in penetrating vessels associated with thrombosis within the penetrating artery or at the stenotic portion of parental vessels (middle cerebral artery or basilar artery). Although capsular warning syndrome is uncommon (1.5- 4.5% of TIA patients), physicians should be alert for this condition because symptomatic or asymptomatic infarcts in the internal capsule/basal ganglia or the pontine base occur in as many as 42-60% of these patients [29, 31] (fig. 2).

Somatosensory Symptoms

Sensory symptoms/signs occur in more than half of stroke patients. However, sensory symptoms as a manifestation of TIA are less common (table 1). This is because patients usually notice the symptoms only when they are positive (e.g. tingling, numb). Although patients may discover that they do not feel as expected when their body parts are in contact with objects (e.g. a spoon, bar or wheel), it is rare to see patients visit emergency departments with this problem as a chief complaint.

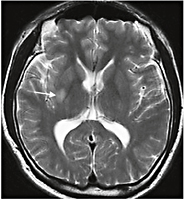

Fig. 2. A 41-year-old hypertensive man suddenly developed recurrent left hemiparesis involving arm, leg and face, and dysarthria that lasted for about 10 min. The episodes recurred 5 times. Neurological examination findings were normal. T2-weighted brain MRI showed a small infarct involving the right putamen and internal capsule (arrow). Transfemoral angiogram findings were normal.

In patients with ischemic stroke, motor dysfunction is often associated with a concomitant decrease in sensory perception in the involved limbs. This is probably the same in TIA patients, but patients simply do not recognize this and thus report the symptom as a pure limb weakness. Moreover, as discussed above, positional or discriminatory sensory disturbances may be perceived by the patients as a ‘weakness’ of the limbs. For these reasons, it is likely that sensory dysfunction in TIA patients is underappreciated.

On the other hand, sensory symptoms are one of the least specific symptoms of TIA (see below). A transient numb, tingling or painful sensation in the limbs may be a symptom of radiculopathy or peripheral neuropathy. Moreover, these also are manifestations of anxiety or hysteria. Hysterical or conversion neurosis should be suspected when the patient is young and does not have vascular risk factors. The patients usually have additional, even multiple, somatic complaints, and do not sufficiently focus on sensory symptoms. Moreover, the distribution of the sensory dysfunction may not fit with the usual clinical pattern (e.g. bilateral hand or feet numbness), although sensory symptoms in the hemibody distribution are also occasionally observed in neurotic patients.

As in stroke patients, sensory TIA is usually accompanied by other neurological symptoms, such as motor dysfunction, and ‘pure’ sensory TIA is uncommon. In 1982, Fisher [32] described 42 patients with pure sensory TIA, in whom the face, arm and leg were involved in 33 (79%), the face and arm in 3 (7%), the arm and leg in 4 (9%), and only the face in 2 (5%) patients. Pathological findings in one patient showed a lateral thalamic infarction. More recently, Kim [33] described patients with repeated, pure sensory TIAs with or without posterior cerebral artery stenosis. The presumed mechanism is repeated hemodynamic compromise of the thalamogeniculate artery in the presence of thrombus within the perforating artery or at the stenotic portion of the posterior cerebral artery. These patients may or may not develop eventual lateral thalamic infarction. Accordingly, this phenomenon is considered a sensory counter-part of capsular warning syndrome. In addition, the author has observed patients who developed occipital infarcts following sensory TIAs associated with posterior cerebral artery stenosis, which may be related to an eventual development of an artery-to-artery embolism arising from the atherosclerotic posterior cerebral artery diseases. Nonetheless, pure sensory TIAs are not necessarily caused by posterior circulation diseases. Recurrent sensory TIAs are occasionally observed in patients with middle cerebral artery atherosclerosis, which may even herald a large middle cerebral artery territory infarction [34].

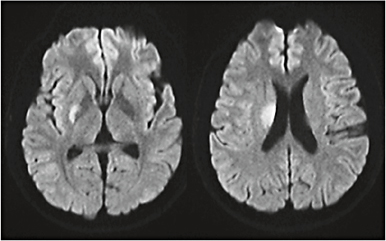

Fig. 3. A 42-year-old hypertensive man suddenly developed two episodes of dysarthria lasting about 20 min each, without any difficulty in walking or using his arms. Neurological examination results were normal. DWI showed an infarct involving the putamen and the genu portion of the internal capsule.

Finally, there are patients who report tingling sensations restricted to bilateral perioral or tongue tip areas. Although this sensory distribution is not specific for posterior circulation diseases, one should be alert on this symptom because it may reflect a significant basilar artery disease, potentially heralding catastrophic brainstem strokes [35].

Speech Disturbances

Speech disturbances are another relatively frequent TIA symptom (table 1) attributed to dysarthria and/or aphasia.

Dysarthria

In TIA patients, dysarthria is usually associated with a motor dysfunction in the extremities or the face. It can be produced by ischemic events occurring on either side of the anterior hemisphere as well as in the posterior circulation. Dysarthria is generally attributed to the involvement of the corticobulbar tract, but it can also be caused by extrapyramidal or cerebellar system dysfunction. Therefore, dysarthria has no localizing value. In addition, it is occasionally difficult to differentiate dysarthria from motor aphasia by history alone. Although uncommon, patients with episodes of lone dysarthria are observed who suffer selective ischemic damage on the corticobulbar tract (i.e. the genu portion of the internal capsule; fig. 3).

Aphasia

As in stroke patients, aphasia in TIA patients can manifest as global, motor or sensory aphasia. In clinical practice, symptoms suggesting motor aphasia (inability to speak) are much more common than sensory aphasia (inability to understand). This is at least in part attributed to the difficulty in differentiating motor aphasia from dysarthria. Moreover, unlike problems that occur during active speaking, limitation in understanding is not well appreciated by the patients unless they are involved in prolonged conversation. Therefore, even if patients report that they did not have particular difficulty in understanding others, it is not clear whether the patients are without sensory aphasia unless they are examined by a physician at the time of the episode. Other types of aphasia, such as transcortical or conduction aphasia, are extremely difficult to detect. Occasionally, patients report that they had difficulty recalling names or words, but again it remains uncertain whether they had purely anomic aphasia by history taking alone.

As aphasia is generally caused by left-sided brain damage, the presence of arterial (internal carotid or middle cerebral artery) disease on the left side more convincingly suggests that the patients’ speech disturbances were due to aphasia. These patients may experience right hemiparesis/hemisensory disturbances preceding, following or at the time of the aphasic episodes. As aphasia is a cortical symptom, it is not observed in capsular or small vessel disease-associated TIA. One study showed that TIA patients with atrial fibrillation more often present with aphasia than those without [36].

Dysphagia

Dysphagia is caused by ischemic damage on the corticobulbar tracts or the nucleus ambiguus and related structures in the brain stem. Therefore, dysphagia is almost always accompanied by dysarthria or other brain stem symptoms. Because dysphagia is often mild or even absent in patients with unilateral corticobulbar tract dysfunction, dysphagia as a symptom of TIA is less common than dysarthria. Furthermore, dysphagia can manifest only when patients eat or drink something, and is therefore less likely to be detected by patients. For these reasons, TIA patients presenting with isolated dysphagia are extremely rare.

Visual Symptoms

Monocular Blindness

Transient monocular blindness (TMB) refers to sudden, brief attacks of partial or complete dimness or obscuration of vision. The term ‘amaurosis fugax’ has been used interchangeably, but not without confusion [37], and TMB, a less controversial term, will be used in this chapter. TMB episodes typically last seconds or minutes. Patients may report that they have complete blindness when the other eye is covered. More often, patients report partial symptoms variably described as ‘things look suddenly gray’, ‘margins of items become blurred’ or ‘curtains are ascending or descending’, or as a gradual shading from the periphery to the center in the affected visual field. Dimming of vision may occur in the upper or lower half of the visual field. Less commonly, scintillations or other positive visual phenomena may occur.

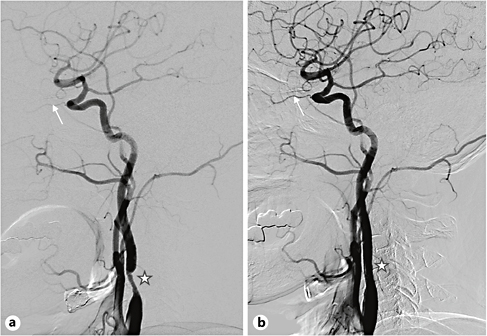

Fig. 4. A 67-year-old hypertensive and diabetic man developed brief episodes of right visual obscuration lasting 1 or 2 min. Brain MRI showed normal findings. a Conventional angiography showed severe stenosis in the proximal internal carotid artery (star) and reduced blood flow in the ophthalmic artery (arrow). b After the stenting procedure, there was improvement of the carotid stenosis and ophthalmic artery flow. The episodes of visual dimness no longer developed afterwards.

TMB is usually associated with significant carotid atherosclerotic stenosis/occlusion (fig. 4) and occasionally co-occurs with contralateral hemiparesis [38]. Although carotid disease at the bulb area has traditionally been described as the cause of TMB, TMB caused by distal (usually cavernous portion) internal carotid artery disease is occasionally observed in Asia where intracranial atherosclerosis is prevalent.

Transient embolic occlusion of the ophthalmic artery, central retinal artery or the posterior ciliary arteries secondary to the detachment of platelets or cholesterol crystals from ulcerated plaques seems to cause TMB. Ophthalmic examination may show an occlusion of retinal arteries by cholesterol crystals (Hollenhorst plaques) or platelet-fibrin. However, normal ophthalmic examination findings at the time of TMB do not necessarily indicate the absence of embolic material. The symptoms are often associated with hemodynamically unstable conditions such as dehydration, sudden standing, and exhaustion, and angiographic studies frequently reveal decreased perfusion in the ophthalmic artery (fig. 4). Therefore, periodic reduction in ophthalmic artery blood flow seems to play an additional role in TMB.

Regardless of the presence of TMB episodes, the presence of retinal emboli predicts higher all-cause and stroke-related mortality than in patients without these findings. In patients who show cholesterol embolus in the retina, the annual mortality rate is four to five times greater than in those without, with the most frequent cause of death being either coronary heart disease [39] or stroke [40].

In some patients, TMB occurs less rapidly, lasts longer (minutes to hours), and ameliorates more gradually (sometimes called TMB type II). Typically, patients’ visual symptoms occur when they are exposed to bright light [41]. Rather than perceiving a significant decrease in visual acuity, patients describe that bright objects appear brighter and more dazzling, so that they have difficulty in seeing objects clearly. They often cannot read letters written on white papers.

These symptoms are associated with very severe carotid stenosis or complete occlusion. The episodes are preceded by hypotension, exhaustion, and conditions associated with increased venous pressure such as stooping or straining or a warm environment. Temporarily lowered retinal artery pressure secondary to severe carotid hypoperfusion and diversion of blood to the external carotid artery system is considered a likely mechanism. Ophthalmic examination shows lowered retinal artery pressure and occasional retinal venous stasis. Aggravated symptoms upon light exposure may be explained by the inability of borderline circulation to sustain the increased retinal metabolic activity associated with light exposure or delayed regeneration of visual pigments in the pigment epithelial layer. Bilateral visual loss associated with severe bilateral carotid occlusive disease has also been reported [42].

In addition to carotid atherosclerosis, TMB may be caused by carotid artery dissection, atherosclerosis on the aorta, and arteritis (such as giant cell arteritis and Takayasu disease). Embolism from heart disease, a systemic coagulopathy (e.g. polycythemia vera), leukemia, and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome may also be associated with TMB.

Finally, some patients show repeated TMB but without any evidence of carotid disease or other embolic sources. In at least some of these patients, retinal or ophthalmic artery vasospasm seems to be the cause of the TMB (TMB type III) [43

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree