Front Neurol Neurosci. Basel, Karger, 2014, vol 33, pp 1-10 (DOI: 10.1159/000351883)

______________________

History of Transient Ischemic Attack Definition

Jay P. Mohr

Doris & Stanley Tananbaum Stroke Center, Neurological Institute, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, N.Y., USA

______________________

Abstract

Transient ischemic attacks have been recognized as a clinical entity for well over a century. Efforts before the availability of modern imaging to establish a diagnosis of inferred ischemic stroke led to acceptance of too long a time period (>24 h) compared with the actual typical events lasting <24 min (usually 5-15 min). Revision of the time period has improved diagnostic yield and discovered many whose image-documented acute infarct is associated with a short clinical course.

Copyright © 2014 S. Karger AG, Basel

As of January 2013, PubMed contains close to 20,000 references in which transient ischemic attack – also known as TIA – is cited in the title or keywords. This large a number suggests the subject has become one of the many acronyms in clinical medicine, its definition and application familiar to all. Sadly, not entirely so.

As a starting point, the ICD-9 code, in common use, for code 435 ‘transient cerebral ischemia’ (no mention of attacks) is notable to its lack of detail. No mention is made of time, the mechanism is inferred to be ‘…vascular insufficiency’ and excludes that most ambiguous of diagnoses, ‘acute cerebrovascular insufficiency NOS [not otherwise stated]’. Little wonder those entering the neurovascular field are unclear on the setting where the term TIA can be applied (table 1).

There are rare references to intermittent symptoms discovered at autopsy due to infarction dating well back past the prior century [1]. (Limits of reference numbers for this chapter preclude many citations, leaving the author to the use of examples.)

Table 1. Various sets of terms used to describe TIA in ICD-9 coding

435 Transient cerebral ischemia |

Includes |

Excludes |

‘Attack’

Working backwards through the elements, the term, ‘attack’, suggests something sudden. The published experience emphasizes a change from normal, but none of the current definitions clarifies whether the event reaches its peak of neurological features immediately, or the means by which the syndrome fades to normal.

The best characterized have been those affecting vision in one eye. Published reports and the author’s experience with patients have – in the vast majority – cited a shade falling smoothly over vision, some completely to the bottom, some stopping usually midway. The loss of vision is usually described as blank, rarely black. Although the term ‘curtain’ has been used, the term usually refers to the modern theatrical straight-across curtain falling from above, not the classical curtain which lifts from the center to the upper corners of both side. The author has found no examples of a ‘shade’ which appears to move to or from the side as in a sliding door. Fortification features have not been described. One remarkable report cited recurrent sectoranopia abnormalities and was traced to a stenosis of a retinal branch [2]. Fisher’s famous case, published in 1959 [3] required approximately 45 min for the white plug to work its way distally and disappear, vision improving in the wake of the clearing. His attempts to explain the mechanism have left some authors citing embolism, others perfusion failure from high-grade stenosis in a feeding vessel.

For hemispheral or brainstem syndromes, most clinicians have heard from patients of a premonitory general sense of unease, some vaguely aware something was in the offing but undefined until the focal features appeared, some hours, others over a day or more later. (The delay in symptomatic onset has been amply demonstrated by many unpublished cases where an aberrant embolus during a catheter procedure generated angiographic evidence of the embolus, but the focal neurological event was delayed minutes to hours later. Such delays challenge common assumptions that the symptomatic onset coincides with the time of occlusion.)

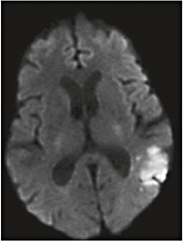

The reported focal features have also shown intensification in either quantitative (e.g. more weakness) or qualitative (e.g. weakness then also numbness) degree, some-times both occurring in the same attack [4]. Convexity TIA and stroke may feature pseudo-median or pseudo-ulnar syndromes [5]. Isolated mutism [6] or sensory aphasia are unusual, but a recent case seen by the author suffered mutism for < 10 min; seen at the end of the time period by a group of experienced neurologists, he passed for normal on examination, busily working with his wife to pay monthly bills while hospitalized for cardiac disease. A focal DWI-positive infarct was found just posterior to the superior temporal plane (see fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Symptomatic focal DWI-positive infarct with syndrome lasting 10 min.

Little wonder many can be diagnosed as migraine aurae. No definition yet accounts for these variables, as the main emphasis is on the inferred ischemic nature and duration. The current ICD9 code for diagnosis leaves the features of the clinical syndrome up to the clinician to decide.

‘Ischemic’

That such attacks are by definition ‘ischemic’ has been challenged by many critics, who point to the brief migraine aura, non-convulsive epilepsy, even a few examples of small parenchymatous hemorrhage with subsidence of the symptoms. There is also ample literature to demonstrate the ischemic symptoms may experience rapid improvement (within hours) despite documentation of clinically correlated focal brain infarction. Further, examples have been published of a susceptibility of symptomatic relapse from exposure to benzodiazepines administered up to a week after disappearance of symptoms and brain imaging showing no DWI-positive foci [7].

Brief events have also been described from a large variety of ischemic causes, among them paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, bacterial endocarditis, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, arterial dissections, minor embolism via patent cardiac foramen ovale, even the first stage of ruptured aneurysm [8].

‘Transient’

Even the time frame suggested by term ‘transient’ has been a subject of a wide spectrum of definitions. The modern history dates from 1954 at the second Princeton Conference (all the biannual conferences were held at the Nassau Inn in Princeton, NJ, until the conference began its peripatetic movements in 1980).

The first, held under the auspices of the American Heart Association, with NY Hospital/Cornell Cardiologist Dr. Irving S. Wright as chairman, and Cornell Internist E. Hugh Luckey, as editor, was simply titled ‘Cerebral Vascular Diseases’. It was attended by many of the small cadre of leading neurologists of the time, including R.D. Adams and C.M. Fisher (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston), J.M. Foley (then at Boston City Hospital), H.H. Merritt (Neurological Institute, New York), C.H. Millikan (Mayo, Rochester, Minn., USA). Dr. Ellen McDevitt (also of Cornell) presented results of treatment of valvular heart disease and atrial fibrillation with warfarin.

The second conference, in 1956, the number of attendees much larger, included R.G. Siekert (Mayo, Rochester, Minn., USA), W.R. Brain (Maida Vale, London, UK), E.A. Gurdjian (Wayne State, Detroit, Mich., USA), A. Heyman (Duke, Durham, N.C., USA), J.S. Meyer (Baylor, Houston, Tex., USA), P. Scheinberg (U Miami), and J.P. Whisnant (Mayo, Rochester, Minn., USA). C.M. Fisher made an oral presentation titled ‘Intermittent cerebral ischemia’. In it, he provided an extensive characterization of ‘transient ischemic attacks’ which he noted ‘…may last from a few seconds up to several hours, the most common duration being a few seconds up to 5 or 10 min’. The published report of the discussion shows no disagreements with this definition, or the brief time frame, in the published report of discussion afterwards [9].

Sufficient interest in the subject led to a publication in an issue of Neurology (the journal Stroke still in utero) titled ‘A classification of and outline of cerebrovascular diseases’ [10]. The authors included many who had attended the conference. Included in the definitions was one for ‘cerebral infarction’, which noted ‘The neurologic deficit may be maximal when first discovered or may require several hours or even a day or so to evolve’. (All this text was generated by authors whose experience was based on clinical evaluation, most of whom had had some training in neuropathology. Tissue imaging by the likes of CT and MR was decades in their future.)

By 1961 when the 3rd Princeton Conference was held, interest in the time-based definitions for stroke had progressed to a ‘TIA Working Group’ led by J.F. Toole (Bowman Gray, Winston Salem, N.C., USA). R.G. Siekert, attending his third Princeton Conference, offered a definition of three stages of focal arterial disease, the last being ‘completed stroke’, describing ‘a focal neurologic deficit, which is stable for hours or days and then tends to decrease in amount’. At the same conference, C.M. Fisher presented findings on anticoagulant therapy from the National Cooperative Study begun in 1958. Fisher offered the view ‘transient ischemic attacks (T.I.A.)…. refers to the occurrence of single or multiple episodes of cerebral dysfunction lasting no longer than one hour and clearing without significant residuum’ [11].

As before, no specific time frame was provided for diagnoses of ischemic stroke attributed to thrombosis and suspected thrombosis or embolism. In a later chapter in the conference proceedings, R.N. Baker refers to most of his cases of ‘completed’ strokes as having ‘been stable for more than 48 h’ [12].

Despite these publications, the literature failed to reflect much impact on the time frame. The only reference found by the present author for duration was that of Acheson and Hutchinson. In their 1964 article titled ‘Observations on the natural history of transient cerebral ischaemia’ they note that that attacks’…should be less than one hour’ [13].

Also in 1964, John Marshall, then the leading neurologist for stroke in the UK (cited by one retired French neurologist as ‘then the sheriff in these parts’) published a single-author review in the Quarterly Journal of Medicine entitled ‘The natural history of transient ischaemic attacks’ [14]. The case material cited 75 cases as lasting ‘minutes’, 17 ‘30 min’, 13 ‘1 h’, and 38 ‘several hours’. (No definition was given for ‘several’.) He defined transient ischemic attacks as:

‘A disturbance of neurological function of less than 24 h’ duration occurring in the territory of supply of the carotid or vertebrobasilar arteries…’… ‘…the typical T.I.A. is an attack of only brief duration, usually lasting less than five minutes. More prolonged attacks, however, do occur, and although transient is perhaps a misnomer, they do share the characteristic of leaving little or no residual deficit. The same can, of course, be said of a small percentage of major strokes; hence some arbitrary time limit has to be set.’

He made no reference to earlier proposal of TIA as brief as 5-10 min. After an interval of 14 years, in 1977 he and co-authors M.J. Harrison and D.J. Thomas published in the British Medical Journal an article entitled ‘Relevance of duration of transient ischaemic attacks in carotid territory’ [15]. They cited 116 patients, separating them into group 1 (<1 h), group 2 (>1 h), and group 3 (both types). Those with angiographic findings of stenosis or atheroma were mainly in group 1. Independently, the same year M.S. Pessin, G.W. Duncan, J.P. Mohr and D. Poskanzer published an angiographic study of carotid TIA in 115 patients in the New England Journal of Medicine [16]. This work at the Massachusetts General Hospital was a substudy from the National Institute on Neurological Disease and Blindness (NINDB) cooperative project. Those with severe stenosis or occlusion had TIAs lasting 5-15 min; those with widely patent carotids had events lasting well beyond an hour.

No revision of the timetable appeared in any of the major statements of disease definitions even as late as 1975 [17].

In the mid-1980s, anticipating trials to intervene early in hopes of aborting developing ischemia [18], NINDS funded a contract to study the timing of appearance of abnormalities on CT scan and the then early MR scan. The two centers Columbia University and the University of Iowa were able to enroll 80 patients in a 180-min time frame [19]. Sixty-eight patients were recruited within 4 h, and an additional 12 patients within 24 h. Seventy-five strokes were due to infarction and five to hemorrhage. The median time to first scan was 132 min. Although some of the infarctions in 75 patients were detected within 1 h, the fraction of positive first scans approached an asymptote at 2-3 h. There was a marginally significant correlation between early positive brain imaging and the severity of the stroke. Some patients had initially positive CT and/or MRI scans, but their neurological examination had returned to normal by 24 h. This study helped settle a 90-min window for acute ischemic imaging and indicated treatment outcomes could be improved by earlier treatment [20].

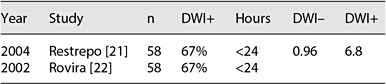

Table 2. Time from event to DWI imaging, percentage positive or negative

Table 3. Summary of the literature showing duration of events and percentage DWI+

Duration of symptoms | Total (n = 2,206) |

>24 h CT/MR+ | 1,498(67.9%) |

>24 h CT/MR- | 568 (25.7%) |

<24 h CT/MR+ | 140(6.3%) |

The following decades saw the widespread use and improved imaging by MR. The two publications cited in table 2 are among many examples showing a striking percentage of DWI-positive foci for patients imaged well within the 24-hour time frame. These publications clearly documented 24 h was too long to wait to decide if the acute syndrome was a stroke, but left unclear how many might experience syndrome remission. The clinical findings of these patients with absent imaging data would have earlier been classified on clinical grounds alone as a TIA.

As an example of the impact of modern imaging, the large Warfarin Aspirin Ischemic Stroke Study (WARSS) attempted to introduce the 1-hour definition, based on the CT/R study, but yielded to the <24 h given the wish to relate the findings to those of other trials (table 3). Yet, even in the WARSS the baseline data contained 6.3% whose initial CT or MR was positive for the event despite imaging done within 24 h [23].

Modern Redefinition

Alert to the ambiguities in the definitions, and wishing some improvement in definitions, Boehringer Ingelheim sponsored a series of meetings hoping to generate a modern definition. Held in several attractive resort sites, the participants worked up a se-ries of presentations, which finally culminated in the proposal published in 2001 in the New England Journal of Medicine [24].

We propose a new definition for TIA encompassing the concept that patients who experience a TIA will have no objective evidence of acute infarction in the affected brain region. Therefore, patients who have transient focal symptoms of brain ischemia – and upon diagnostic evaluation are found to have an acute brain infarction – would no longer be classified as having a TIA, regardless of the duration of clinical symptoms. With this new definition, the difference between a TIA and a stroke becomes similar to the distinction between an episode of angina pectoris and an MI. Angina is a symptom of cardiac ischemia, which is usually brief but may be prolonged, without MI. If there is objective evidence of myocardial damage, then the term ‘MI’ is applied.

We propose the following redefinition for the term ‘TIA’:

A transient ischemic attack (TIA) is a brief episode of neurologic dysfunction caused by focal brain or retinal ischemia, with clinical symptoms typically lasting <1 h and without evidence of accompanying infarction.

The corollary is that permanent clinical signs or appropriate brain imaging abnormalities define cerebral infarction – that is, stroke. While preserving the TIA concept, this new definition abandons the arbitrary 24-hour limit and substitutes general parameters that more closely match the typical duration of TIAs. Furthermore, the specific exclusion of patients with acute brain infarction serves to more clearly distinguish a TIA from a stroke. This redefinition is more in keeping with the definitions used to describe myocardial ischemic events.

A limitation to this concept is that patients who receive brain imaging studies for the evaluation of their TIAs may be classified differently than individuals who are not imaged. However, as neurodiagnostic procedures continue to advance, the proposed definition allows patients to be classified based on the best available data for the individual patient. In addition, the new definition avoids assigning an arbitrary time limit for the maximal duration of a TIA. For example, a patient with a 2-hour clinical episode that causes a small brain infarction would be classified as having a stroke rather than a TIA, while a patient with an identical episode and no evidence of acute infarction (either because no imaging was performed or imaging studies were negative) would be diagnosed with TIA.

Current Impact of the Modern TIA Definition

The impact of the 1 h rule on current schemes for diagnosis seems at best to have been minor. The current ICD9 coding document has no reference to timing.

There is ample modern evidence that confirms earlier impressions that TIA is a predictor of subsequent ischemic stroke, and that the time between TIA and stroke can be quite short: 8-10% during the 7 days after a TIA or minor stroke [25–27]. It is also clear that early intervention has a major effect on reducing the subsequent ischemic stroke risk [28].

Despite the steadily accumulating evidence, even the elegant and practical scoring systems recently devised to identify risk factors for stroke after TIA continue to use the 24 h rule [29, 30]. A similar reliance on the ‘classical definition, a TIA was defined as an acute loss of focal cerebral or ocular function with symptoms lasting <24 h…’ is found in a recent large 2-year study of efforts to diagnose the subsequent stroke using a variety of etiology classification [31].

In the nearly 5 decades since the initial efforts to define a time frame for TIA, clinical trials of ischemic stroke continued to use a <24 h definition when classifying events. The reason seems to have been the hesitation to introduce new definitions where the trial was intended to assess a given agent’s effects as prophylaxis or reversal of an acute stroke syndrome.

In the current year (2013), the <24 h definition still applied to all seven of the articles cited in PubMed with transient ischemic attack in the title. Many of these articles were large national databases stretched over several years. One report [32] noted the reclassification of the event into stroke if imaging demonstrated an acute infarct; no data were presented for the frequency of this group.

None of these publications are criticized for their focus on outcomes, only for the difficulty assessing which of the events lasting <1 h prove to be the majority, or, more likely, remain among those disregarded as too brief to be important, too brief to create a sense of concern, and too brief be transported to a clinical setting for evaluation. The development of centers for acute evaluation of TIA is a welcome development, and can be hoped to expand insights into the fate for the brief attacks [33].

As a starting point, the ICD9 code for ‘transient cerebral ischemia’ (no mention of attacks) is notable for its lack of detail. No mention is made of time, the mechanism is inferred to be ‘…vascular insufficiency’ and excludes that most ambiguous of diagnoses, ‘acute cerebrovascular insufficiency NOS [not otherwise stated]. Little wonder those entering the neurovascular field are unclear on the setting where the term TIA can be applied.

The current 2013 ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Code G45.9, to be replaced in 2014, represents some progress:

Transient cerebral ischemic attack, unspecified: recurring, transient episodes of neurologic dysfunction caused by cerebral ischemia; onset is usually sudden, often when the patient is active; the attack may last a few seconds to several hours; neurologic symptoms depend on the artery involved.

A brief attack (from a few minutes to an hour) of cerebral dysfunction of vascular origin with no persistent neurological deficit.

Applicable to:

Spasm of cerebral artery

TIA

Transient cerebral ischemia NOS

Transient cerebral ischemic attack, unspecified

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree